CHAPTER ONE

TREES, ANIMALS, ENGINES

There are no sagas—only trees now, animals, engines: There’s that.

William Carlos Williams, Notes in Diary Form, 1927

William Carlos Williams voiced a new worldview when he wrote that his was an age of “trees, animals, engines.” For one thing, he acknowledged the proliferation of machines and structures in contemporary life. Trolleys, telephones, and automobiles, etc., were everywhere on the landscape. Sheer numbers made a claim for their recognition. Williams’s statement is a concession to a new reality. It suggests a new outlook in which the bridge and the engine would be equal in status to animals and plants.

Two relevant issues underlie Williams’s statement. The first, as we see, is logistical. The trees, animals, and engines could be listed as equal items in a series simply because technology was so pervasive in American life. It impinged on consciousness everywhere in the home and on the street. The traditional natural world of flora and fauna now included machines and structures.

Williams’s observation, however, goes much further in its assumptions about the relation of technology to nature. As we shall see, it makes an important statement about contemporary perception. Quite simply, Williams joins trees, animals, and engines together because he, like many of his contemporaries, presumes that the structural principles of these phenomena are identical. For Williams, trees and animals, like machines and structures, were integrated systems of component parts. He sees them as categorical equals because they are anatomical analogues of each other. Perceiving in this way, Williams had every reason to join organism with mechanism. Both, in his view, were comprised of functional, integrated components. The body’s skeletal and digestive systems had their counterparts in the structures of the tree and the automobile. Structurally they belonged together. When Frank Lloyd Wright proposed that “an entire building might grow up out of conditions as a plant grows up out of soil” and added that the tree is the “ideal for the architecture of the machine age,” he only elaborated Williams’s position. He, like Williams, saw the structural similarity between organic and inorganic forms. Both he and Williams recognized a similarity between nature’s mechanisms and man’s (Autobiography 147).

The perception of trees, animals, and engines as structural analogues had far-reaching implications for imaginative literature, as we shall see. It eventuated in a new conception of the novel as a designed structure of component parts, of the sentence as a structuring component of fiction, and of the poem as a mechanism comprised of constituent word-objects. This perception is the basis on which the technological revolution of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century America was really a revolution in language as well as in engineering.

These matters, however, must await further discussion. For the moment we begin with the logistical side of Williams’s remark, with his assumption that technology is as omnipresent in modern America as its flora and fauna. Briefly we must survey an America of trees, animals, engines. To do so is to see a nation that perceives technology mixing freely with nature both in the external environment and in the popular media. Middle-class periodicals presented this America both in visual and verbal texts from journalism to advertisements. Popular magazines are a valuable source showing how many Americans of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were encouraged to think about machine technology in contemporary life.

This opening discussion will also reveal the development of a new machine-age consciousness. The proliferation of machines and structures in American life between the 1890s and the 1920s began to make itself felt in popular and serious fiction. Novels of commercial and artistic intent showed a new consciousness of a world of “trees, animals, engines.” Mixed metaphors of nature and machines abutted each other even in novels whose themes were antitechnological. Fiction offered a good opportunity to see this cultural amalgamation of technology and nature, especially in the work of Frank Norris, Jack London, and Edna Ferber.

As we shall see, this process of amalgamation occurred with such rapidity that it often had the appearance of discontinuity. Suddenly loosed from their separate categories, technological and organic figures of speech seemed to jostle each other, suggesting the tensions that invariably arise in times of rapid sociocultural change, when the old order seems to vanish in the onrush of the new. The novelist Edith Wharton (1862-1937) summarized the pace of this change. Born in an America that still adhered to Old World traditions, Wharton lived to see them repudiated in modernist America materially characterized by “telephones, motors, electric light, central heating, X-rays, cinemas, radium, aeroplanes, and wireless telegraphy [which] were not only unknown but still mostly unforeseen” (Backward Glance 6-7).

Wharton refers to a culture of discontinuities, one wrenched in the process by which values and material circumstances undergo rapid change. It is important to examine the enactment of those discontinuities in the very texture of imaginative writing. Of course not all writers experienced tortuous change. Williams and Wright, men trained in technological disciplines (in medicine and engineering-architecture, respectively), were comfortable with their perceptually unified world of trees, animals, and engines. They had reason to be, having learned to see the objects in the material world as designed assemblies of integrated component parts. Writers further away, however, from immediate sources of such perception felt caught between tradition and change in a post-Darwinian world that seemed above all unstable. It is perhaps surprising to find that their writings, nevertheless, prepared the way for technology’s new prestige and its formal enactment in fiction and poetry.

MAGAZINE MACHINESCAPES

Logistically speaking, technology was everywhere on the American landscape by the turn of the twentieth century. Rail and telegraph lines were a commonplace, and citizens even of smaller towns saw their dusty streets dug up for water, gas, and sewer lines, and poles sunk for the new telephone wires. Those living along the major river valleys of the Ohio and Mississippi had seen, and continued to see, mammoth bridge construction, and every medium-sized city could boast a tall, metal-frame building of the kind to be known as skyscrapers. For middle-class families the automobile and home electrification were just in the offing.

Personal knowledge of technology, however, exceeded the experience of one’s family or hometown, whether in the metropolis or the heartland. The burgeoning, successful American magazines like Cosmopolitan, Harper’s Weekly, Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, The Ladies Home Journal, and Literary Digest brought images of technological values and accomplishments into middle-class American living rooms weekly and monthly. A subscription to a mainstream magazine, even one specialized for children, for homemakers, or for businessmen, was a guarantee that the reader would be made constantly aware of the national and worldwide presence of machines and structures. Journalism and advertising saw to it. To scan some of these periodicals is to see that Americans from the 1890s to the 1920s were systematically taught that technology was no longer confined to the factory grounds. Virtually all readers learned that they now inhabited a world of “trees, animals, engines.”

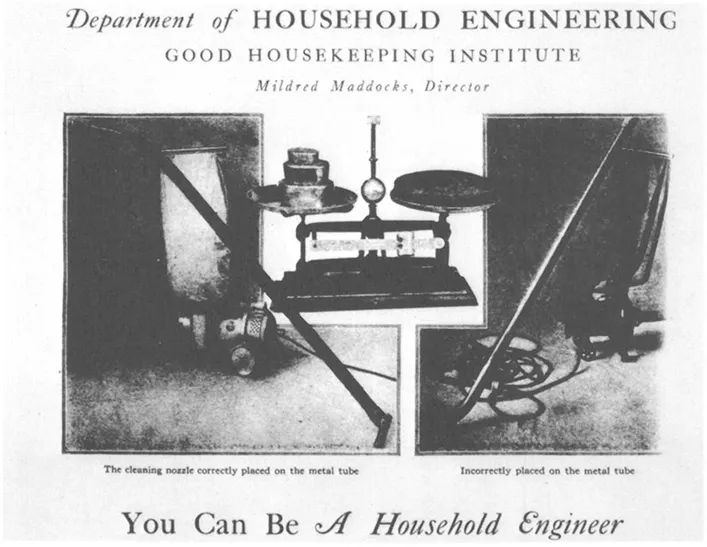

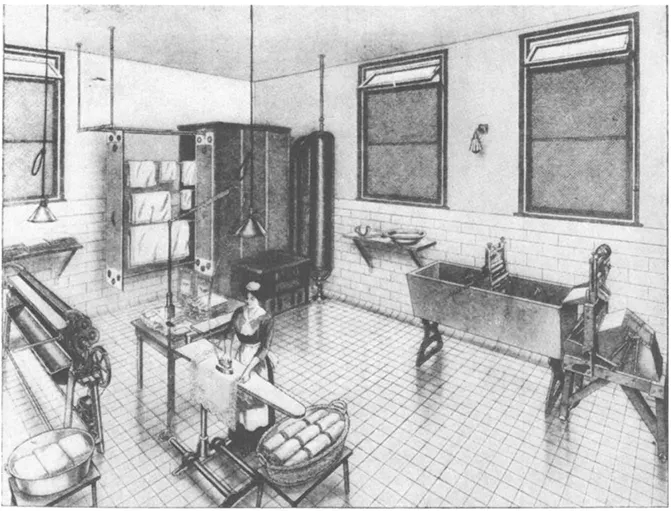

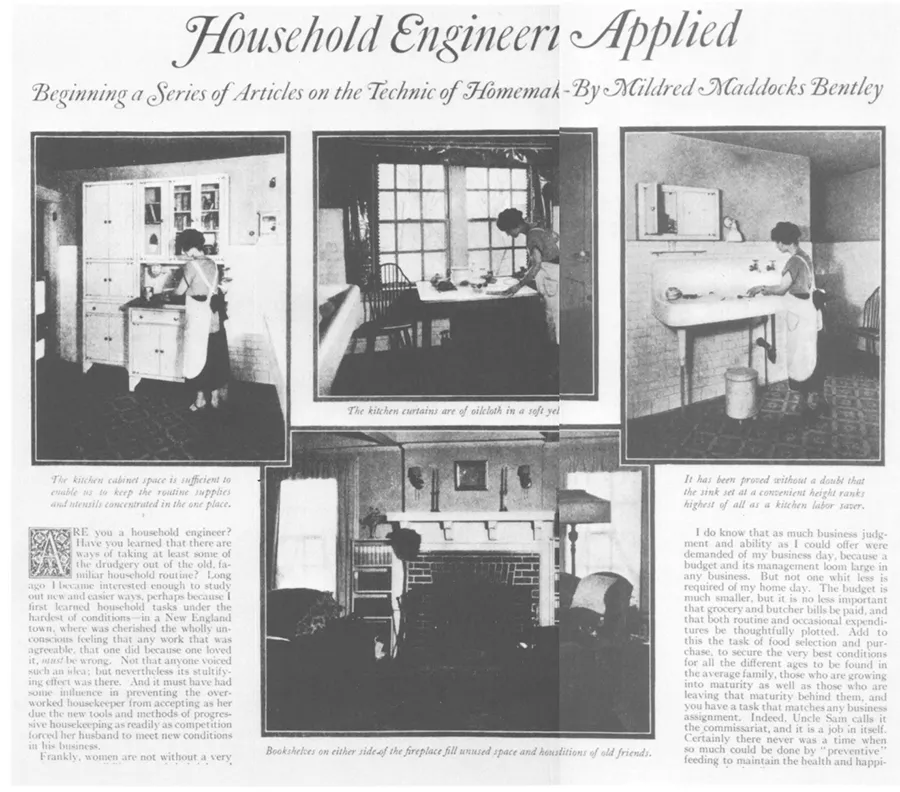

The home provides a good example of the magazines’ role in technological consciousness-raising. A subscriber to the Ladies Home Journal (LHJ) was offered, via advertisements, a range of technological equipment including cameras, bicycles, furnaces, electric dishwashers, irons, waffle irons, phonographs, automobiles. These objects were unified in the concept of the home as factory, and the lady of the house as engineer. Good Housekeeping (GH) (1910) said that “a house is nothing more than a factory for the production of happiness” and urged that it be equipped accordingly, with machinery” (58:525). The magazine’s famous institute offered a booklet entitled Household Engineering, which promised that the technical ability heretofore applied to the factory and business world would now be devoted to “a housekeeper’s engineering problems” (67 [Oct. 1918]: 45). Similar articles in Technical World and Woman’s Home Companion included “Running the Home Like a Factory” and “Training the Home Engineer” (23 [July 1915]: 589-92; 53 [Feb. 1926]: 42). One 1920 article presented a young bride aghast at the first sight of her new mechanized kitchen. She exclaims to her husband, “You know I did not have a course in machinery at the finishing school!,” only to hear him say that a happy marriage will result from these labor-saving machines, those which the Hotpoint Corporation vowed originated with “a housekeeping engineer—not in some casual workshop” (LHJ 37 [Sept. 1920]: 3; 39 [Apr. 22]: 173). If such articles show the extent to which disempowered women were co-opted in an industrial age, they also mark the deep incursion of technology into the domestic sphere.

In one respect, in fact, the homemaker was crucial to the encouragement of technological activity, since advertisers bought space in women’s magazines to promote such toys as steam engines, electrical sets, motorboats, and construction kits for boys, most of them appealing on the basis of education, motivation, and character development. (Erector, typically, promised mothers to “help prepare [their boys] for the business world by developing ambition” and promised to “encourage imagination, concentration, ingenuity and skill—and increase chances for success as a man”) (LHJ 33 [Dec. 1916]: 85; Collier’s 58 [Dec. 9,1916]: 22-23).

Boys themselves could alternate hands-on play with forays into encyclopedic literature intended to explain the new world of machine processes. One good example, The Book of Wonders (1916), shows precisely how the young (or adults for that matter) would understand the era as one of trees, animals, and engines. Typically the book tells the “story” of some item in daily use, such as a suit of clothes or rubber tires, moving from photographs of pastured sheep and plantation rubber trees to a pictorial display of the complicated machinery that completes the story by turning wool and sap into cloth and tires. The world’s “wonders” are both natural (“Why the Moon Travels with Us”) and technological (“The Story in a Submarine Boat”). The book’s cover sends that very message, displaying the double image of a wise old owl whose head and eyes also become the world rotated, Archimidean-fashion, by belts and pulleys.

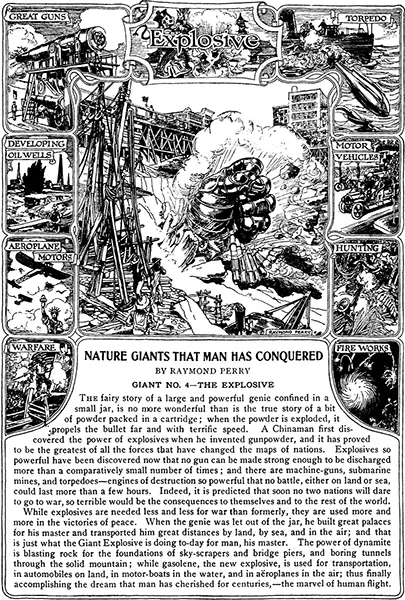

Middle-class youngsters with access to wonder books would probably also enjoy subscriptions to a children’s magazine like St. Nicholas, which relegated the sewing machine and the camera to little girls, but offered boys a world of adventure in the realm of the engineer and inventor. To turn the pages of St. Nicholas from the turn of the century is to see it define an interesting, worthwhile life as one of adventure and ingenuity. The publisher spared no effort to involve boys in contemporary machine and structural technology. One illustrated series—“Nature Giants that Man Has Conquered”—portrayed human triumph over natural forces via steam, waterpower, electricity, chemistry. There were also inspirational feature stories on prominent inventors like Edison (“The Boyhood of Edison”), George Westinghouse, and the explosives wizard Hudson Maxim (whose book on literary criticism, as we shall see, made Ezra Pound conscious of the technological values inherent in language). One St. Nicholas series, entitled “With Men Who Do Things,” invited young readers to identify with the boy-narrator and his friend, both transported to major civil engineering sites, where they work and learn the design principles of elevators, suspension bridges, tunnels, dams, explosives, submarines, electrical power stations, skyscrapers, the Panama Canal locks and excavations, waterway diversions, and industrial machinery. Photographs, illustrations, and diagrams vividly enhanced the text, doubtless increasing the attraction to young readers.

Illustrations of precise food measurement and of efficient and wasteful vacuuming. Good Housekeeping, 1919

Mechanized home laundry. Good Housekeeping, 1913

The well-engineered household. Ladies Home Journal, 1925

Technological exploitation of explosives. St. Nicholas Magazine, 1911

“With Men Who Do Things” was evidently so successful a series that St. Nicholas followed it up in 1916-17 with another entitled “On the Battle-Front of Engineering,” emphasizing that ingenuity can triumph over natural and man-made perils, including floe ice and tunnel collapse. The heroic modern life in this periodical was clearly that of the engineer or inventor, and boys were encouraged to think of their place in the technological future, whether as builders of bridges or architects of airships (38 [Apr., May, June, 1911]: 499, 593, 700; 40 [Mar., Apr., May, June, July, Aug., Sept., Oct., 1913]: 402-9, 533-40, 638-44, 735-40, 822-27, 927-33, 1023-30, 1126-33; 41 [Jan., Feb., Mar., Apr., May, July, Aug., Sept., Oct.]: 237-43, 333-39, 421-27, 526-31, 621-27, 837-41, 893-99, 1006-12, 1094-1100).

The husbands and fathers of these same middle-class families also imbibed a steady stream of technological messages from magazines, prominent among them the Literary Digest (LD), forerunner of Henry Luce’s Time. The Digest, as its title implies, distilled stories from a wide range of American periodicals, including journals like Engineering-News, Iron Age, and Cassier’s, all periodicals of professional engineers, as well as Popular Science Monthly and the Scientific American. A reader would have found Digest articles on “The Development of American Industries since Columbus,” “New York’s Great Underground Railroad,” “Some Wonderful Calculating Machines,” “America at the Paris Fair,” “Achievements of Electricity in Human Progress,” and “American Mechanical Supremacy and American Character” (2, no. 7 [Dec. 13, 1899]: 9-10; 20, no. 6 [Feb. 10, 1900]: 183; no. 8 [Feb. 24, 1900]: 247; no. 17 [Apr. 28, 1900]: 505-6; no. 19 [May 12, 1900]: 577; 21 [Oct. 6, 1900]:402).

Engineering and its achievement was a recurrent emphasis in the Digest and in other magazines like Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post. The middle-class male reader heard his magazines tell him that “in this country we have gone further in engineering than any other people,” that “in the progress of engineering we are contributing more than our share,” and that “civil engineers have supplied the grand arches and ribs of steel which made it possible thus to excel in vastness every building enterprise which earth in its unnumbered centuries has borne upon its bosom” (LD 24, no. 6 [Feb. 8, 1902]: 182; no. 11 [Mar. 15, 1902]: 357; Scientific American 71 [Aug. 11, 1894]: 87).

Many articles emphasized the power and resourcefulness of engineering. “The Greatest Bridge in America,” “Seventy Years of Civil Engineering,” and “Character in the Engineering Profession” were typical and went hand in glove with articles like “The Mighty River of Wheat” in Munsey and “Gigantic Labor Savers” in Collier’s, whose text and large-format photographs extolled the wonders of powerful machines from reapers to conveyer belts. All such articles endorsed the ingenuity of those conceiving, building, and using machinery. They invited the reader to enter a state of informed awe. The American middle-class man, like his son, learned that modern progress was the result of ingenuity and the development and application of machines and structures all over the world. The family parlor magazine rack held constant reminders that the old American agrarian world was transforming itself into one in which machines and structures took a proper place in the field, on the farm, and even in the forest (Collier’s 32 [Dec. 19, 1903]: 7-8; Scientific American 112 [June 5, 1915]: 527-33; 71 [Aug. ...