![]()

Chapter One: Coming

of Age in Mississippi

The Life and Times of Warner McCary

Antebellum Natchez was a bustling city perched “on a most beautiful eminence” overlooking the Mississippi River. It had long been a hub of social, cultural, and economic exchange for southeastern Indians and newcomers from Europe and Africa, and in the first decade of the nineteenth century, the lively port was experiencing unprecedented growth. Most days, the water throbbed with boats almost a mile down the riverbank. In 1808, travel writer Christian Schulz estimated that there were about three hundred houses and nearly three thousand inhabitants, “including all colours.” His impressions of the city—the swagger of the wealthy planters, the brawls between sailors over a “Choctaw lady,” and the “misery and wretchedness” of the enslaved—suggest a vibrant but volatile atmosphere. The gentlemen of Natchez, Schulz surmised, “pass their time in the pursuit of three things: all make love; most of them play; and a few make money. With Religion they have nothing to do.”1

Although Schulz overestimated the Natchez population—it was closer to 1,700 than 3,000 in 1810—his perceptions of the bustling port captured the city’s economic and cultural vitality.2 It was a place of opportunity, and though the population grew relatively slowly compared to other cities on the Mississippi River, it was home to an incredibly diverse array of people. In addition to the emergent American planter elite, Natchez and the surrounding area known as the Natchez district were inhabited by a variety of French, Spanish, and English immigrants and their descendants, Choctaws and other Native southerners, artisans and merchants from the eastern United States, a significant number of free blacks, and a large population of enslaved people.3 Pennsylvania cabinetmaker James McCary was among the half million eastern migrants who entered the Mississippi Territory in the early years of the nineteenth century, seeking a new life and new possibilities.4 He established himself by purchasing several slaves, at least one of whom would bear his children.5 Just a few years later, a child named Warner would be thrust unceremoniously into this milieu. The difficulty of the enslaved child’s early life would both inspire and equip him to remake himself as a street performer, militia fifer, and ultimately, an Indian.

THOUGH ITS GREAT waters were an undeniable fact of life, the Mississippi River was not a major commercial route until the 1790s. The first European colonists to settle the lower river valley were French, and they alternately traded with and abused the Natchez Indians in whose ancestral lands they insinuated themselves. After years of French insults and encroachments, the Natchez organized a surprise attack in 1729, but were ultimately defeated and scattered by combined Choctaw and French forces, who then took their land and their name for the town. Like many of the French colonial settlements in the southern part of North America, the frontier hamlet of Natchez limped along pitifully for much of the eighteenth century, often subject to the wishes and dictates of powerful neighboring Indian nations. At the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763, it was among the possessions that passed from French to British control, if only on paper, and then into Spanish hands in 1779. In the Treaty of San Lorenzo (1795), Spain ceded the territory that included Natchez and most of the remaining Choctaw homelands to the United States, without bothering to involve the Choctaws in negotiations. By 1798, Natchez was the capital of the newly organized Mississippi Territory, and by the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, it had developed into an important stop on the Natchez Trace, an overland route connecting Nashville to New Orleans.

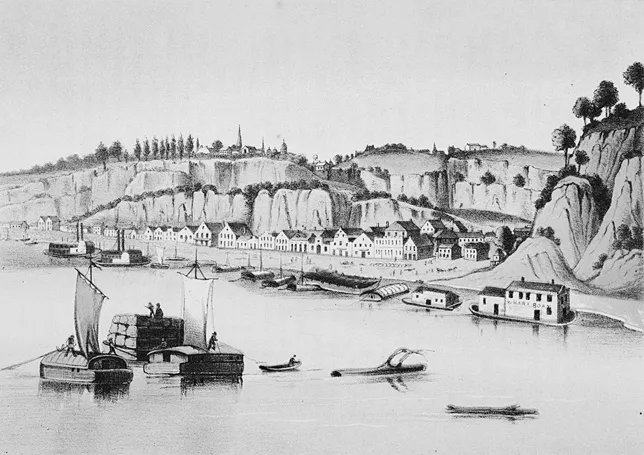

For much of the colonial period, the commercial potential of the region was hampered by European imperial competition intertwined with the determined efforts of Native people to maintain control of their homelands. But just before and after the establishment of the Mississippi Territory, the city experienced a mercantile transformation. To the existing trade in furs, livestock, timber, and indigo, new planters and merchants added incredible quantities of cotton and tobacco. As Natchez grew, it became an important trade depot between Ohio valley ports and the Gulf of Mexico, importing flour, whiskey, and slaves from upriver and sending agricultural products and naval stores downriver to New Orleans and beyond.6 Until the era of steam navigation, most goods were moved downstream on flatboats that were destroyed upon reaching their final destination, their motley crews of Kentucky, Ohio, and Métis sailors returning home on foot or by sea.7 (See Fig. 1.) Schulz observed, “From the brow of the hills before mentioned, you discover small fleets arriving daily, which keep up the hurry and bustle on the flats or Levee below; while at the same time you see detachments continually dropping off for New-Orleans, and the slaves breaking up the hulks of those that have discharged their cargoes, in order to make room for the new comers.”8 Nearly twenty years later, the port was no less busy. In 1824, traveler Adam Hodgson remarked that the landing at Natchez was perpetually “crowded with Kentucky boats, and an odd miscellaneous population.”9

FIGURE 1 Antebellum Natchez. Painted by Henry Lewis during a tour of the Mississippi River in the mid-1840s, this scene captures the bustle of the waterfront, the city of Natchez sitting high up on the bluffs, and Natchez-under-the-Hill down below. The image appears in Lewis’s Das illustrirte Mississippithal, facing page 392. (Courtesy Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library)

During the intervening years between Schulz’s and Hodgson’s sojourns in Natchez, the city had experienced a profound transformation specifically in the realm of agricultural commerce. Early successes in cotton cultivation inspired emigrants who arrived from the East, their numbers growing steadily as new travel routes were opened through Indian lands.10 Newcomers who didn’t already own slaves generally aspired to acquire some and typically sought a parcel of the fertile land in the environs of Adams County. But unless they were extravagantly wealthy, the hopeful were often disappointed and forced to settle for smaller tracts in disputed areas, where they squatted in hopes that their “improvements” would overrule the need for legal purchase or Indian cession.

Migrants’ hopes notwithstanding, the indigenous character of the place was undeniable. Still strewn with the massive earthworks erected by its earlier Mississippian inhabitants, the country showed “signs of having formerly cherished a population far exceeding any thing which has been known in our time,” Schulz noted.11 For example, Emerald Mound, situated just ten miles outside of town, was built by the ancestors of the Natchez Indians and is among the largest surviving mounds in all of North America. In addition to these topographical reminders of Native inhabitance, the city of Natchez itself had been the historic site of the Grand Village of the Natchez people from the late seventeenth century until 1730. Over the subsequent century, Native history would still loom romantically large in local memory.12

Situated along the western boundary of Choctaw territory, the Natchez district was a richly diverse borderland region where Indian, African, and European peoples shaped a social and cultural landscape as complex as any in the Atlantic world.13 Choctaw stories, informed by the histories of other indigenous people with whom they fought, collaborated, or merged, narrated this place into being, and Native paths crisscrossed the land long before any Europeans had thought to blaze their own trails.14

The area’s long history of ethnic intermixture was a matter of fact for inhabitants, but fascinating for outside observers. It became a key theme in popular literary representations of the place, from François-Rene de Chateaubriand’s romance Atalá (1801) to the racially indeterminate cotton pickers of William Gilmore Simms’s short story “Oakatibbee, or The Choctaw Sampson” (1845), which may have later inspired the name “Okah Tubbee.”15 This multicultural environment—a place where “Americans, Africans, and Europeans resisted one another, borrowed from one another, or simply found cultural resonances among one another”—not only inspired Chateaubriand, Simms, and much later, William Faulkner, but also shaped the world of the child Warner McCary who was born about 1810. Although it is impossible to say what precise set of circumstances attended his conception and birth, it took place somewhere in this sultry river valley, where sexual relationships across racial and cultural boundaries were more common than not.16

When James McCary died in Natchez in 1813, his will bore evidence of just such a complicated relationship. It stipulated that four of his slaves, Sally, Frances (or Franky), and “the children of the said Franky, that is to say one called Bob [Robert], and the other called Kitty,” be granted “their freedome forever.” Bob (age 6) and Kitty (4) were to be educated and “brought up in . . . the principles and practice of true religion and morality.” But “the youngest child of Franky,” a three-year-old boy “called Warner,” was to remain enslaved, his “labor and Services, and the proceeds of the same shall be solely for the use and benefit of the aforesaid Bob and Kitty, the children of Franky, Share and Share alike.”17

Although it may at first seem capricious, McCary’s decision to free some of his slaves but not others was not terribly unusual. As one historian notes, “Slaveholders saw no contradiction in doling out liberty with one hand and tightening the chains of bondage with the other.”18 James McCary died a bachelor, but wished to provide for his illegitimate children by bequeathing them wealth in the form of real estate, cash, and slaves, including their apparent half-brother. The young man known as Warner McCary would later describe his “first recollections” of childhood as “scenes of sorrow,” and above all else, it was perhaps the incredible injustice of his being kept a slave and made to serve his own siblings that led the young man to imagine a new family for himself, a new life, and ultimately, a new identity.19

According to Okah Tubbee’s later autobiography, “Mosholeh Chubbee . . . a Chief of the Choctaws, who inhabited a scope of country on the Yazoo River, about one hundred miles west of the Mississippi River” was his father. Tubbee claimed to have been stolen from the Choctaws at a very young age.20 (See Fig. 2.) Although clearly intended to establish Okah Tubbee’s paternal ancestry, the autobiography’s claims on this point are grossly imprecise. “Mosholeh Chubbee” apparently meant Mushulatubbee, a Choctaw chief of the eastern division and noted cattleman, a leader in the tribe’s early national embrace of stock-raising.21 And although the Choctaws did historically inhabit the Yazoo River region in present-day northern Mississippi, it runs to the east of the Mississippi River joining its waters near Vicksburg. Before Indian removal, some Choctaws lived west of the Mississippi River, having agreed to settle in the Arkansas territory in the Treaty of Doak’s Stand (1820), but no Yazoo River flows there.22 The rest of the “Biography” is similarly interwoven with fact and fiction, including a purported covenant between the Iroquois Six Nations and the Choctaws under “Chief Chubbee,” who makes a dying request to the “Oyataw” nation to find his long-lost son.

FIGURE 2 Mushulatubbee. Painted by George Catlin in Arkansas following Choctaw removal, this portrait captures the famous leader’s distinctive appearance and characteristic dress, both of which inspired Okah Tubbee’s self-fashioning. Mó-sho-la-túb-bee, He Who Puts Out and Kills, Chief of the Tribe, 1834. (Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr.)

Although Tubbee confessed in his later autobiography to having an “imperfect recollection” of his Indian father, he nevertheless described him thus: “a very large man, with dark, red skin . . . his head was adorned with the feathers of a most beautiful plumage.” He was supposed to bear “a strong personal resemblance to his father, except the father was taller and heavy built,” the “Chubbee” in his name indicating that the chief was “big and fat.” But the youth was forced to acknowledge a “new father, or a man who took” him to a new home in Natchez. He soon determined that this white man was not his “own father, neither in appearance nor in action” and began to understand that he “could have but one father.” Faced with a family he repudiated, the enslaved youth sought solace in dim memories and comfortable fictions.23

Although it is possible that Warner McCary’s real father was Choctaw, it is less likely that his father was the Mushulatubbee. It stands to reason that a man of such prominence would have complained, petitioned, or at least alerted someone that his cherished young son had been kidnapped.24 It is also possible that Warner was the child of an enslaved woman and an unknown Choctaw man. Another possibility is that he might have once belonged to Mushulatubbee or another Choctaw slave owner. The eastern district chief had more slaves than most other Choctaws, and observers asserted that by the early national period, enslaved people in the Choctaw nation tended to be mostly of African descent, having been purchased or stolen from slaveholding American neighbors. But there is little certainty about any one bondsperson’s particular lineage because some of the slaves imported into Choctaw territory had come more or less directly from Africa, whereas others were brought from the Upper South or West Indies.25 And, like their American counterparts, Choctaw masters were sometimes both owner and father to their slaves. Whether Warner was a missing child, stolen property, or something in between, there is still no evidence that Mushulatubbee ever looked for the boy. Early southern writer Gideon Lincecum lived near the Choctaw chief during the 1820s and recalled that, in addition to his slaves, the chief had two wives (on...