![]()

Chapter 1

Spending, Credit, and the Budget

Political controversies over the size, composition, and economic effects of the federal budget have greatly intensified over the past decade. Despite presidential and congressional efforts to restrain spending, budget growth has been rapid and seemingly uncontrollable, and deficits have reached unprecedented levels. Pressures to reduce spending growth and deficits have heightened the competition between budget priorities, particularly between defense and social welfare spending.

While the travails of the “official” budget have received a good deal of critical attention, direct spending and the fiscal policies necessary to finance this spending are only part of the current fiscal dilemma. Since the early 1970s, federal credit programs have proliferated and expanded dramatically and now represent an important, though largely hidden, form of government spending.1 These programs are a principal component of federal policy in a number of areas—housing, agriculture, education, and international affairs—and have important economic consequences as well.

In fiscal 1972 the amount of federal and federally assisted credit outstanding was approximately $200 billion.2 Ten years later, the total was well over $500 billion, and “one of every eight dollars extended by federal agencies was in the form of a direct loan or loan guarantee.”3 There are perhaps as many as 350 direct loan and loan guarantee programs.4 Funds advanced through these and other federal sources account for more than one-fifth of the total funds advanced in U.S. credit markets.5

Both the Carter and Reagan administrations have attempted to bring federal credit activities under the umbrella of broader budget control efforts. In his fiscal 1981 budget, President Carter initiated a credit budget designed to focus greater attention on the use and economic impact of federal credit programs.6 Two years later, the Reagan administration announced that “rigorous control over Federal credit programs ... is an important part of the President's budget reform plan.”7 Congress has also begun to address problems of credit control and to explore means of integrating credit into the budget process.

Like spending programs, however, federal credit programs are inherently difficult to control, for they provide well-defined and substantial benefits to important constituencies. The desire for fiscal restraint thus collides with political pressures to maintain and even to expand individual programs. And unlike the spending budget, the costs of many credit programs are diffused and largely hidden. As one critic has pointed out, credit programs permit government “to claim that wonder of wonders—something for nothing, or almost nothing.”8 The claim is spurious, but it presents an extraordinary test of the fiscal responsibility of political institutions.

How Spending Is Hidden

The economic impact of federal credit programs extends to the allocation of credit, the composition of the economy, and, ultimately, the productivity and economic growth of the nation. The expansion of federal credit activity, however, is not reflected in the spending and deficit totals in annual federal budgets.

Most direct loans, which require immediate commitments of funds, are charged to off-budget agencies, while the budgetary consequences of guaranteed loans become apparent only in the case of default, when agencies must actually provide funds to repay lenders holding the guarantees.9 Loan guarantees are by far the single largest category of federal credit activity, with the government's contingent liability exceeding $550 billion.10 A wide range of borrowers thus receives assistance with little or no direct spending and, hence, no apparent budgetary costs.

There are other, less obvious, dimensions to the hidden costs of federal credit activities. All credit programs include subsidies, since borrowers receive assistance at lower interest rates or under more favorable conditions than would be available in private credit markets. Indeed, the element of subsidy is the principal reason for utilizing government rather than private credit. Lower interest rates, longer loan maturities, and related forms of favored treatment lower the costs of borrowing. The effective result is a cash grant to the borrower.

The precise cost of such subsidies, however, is often difficult to calculate and, in any case, is usually not translated into direct spending. When direct loans, for example, are extended at rates below prevailing market conditions (or even the interest rates the government pays to finance its own borrowing), their true costs are not reflected in the actual cash transactions, even when these transactions are handled by on-budget agencies.

The obscuring of costs is even more evident with loan guarantees. Federal guarantees typically allow borrowers to obtain funds at lower rates by eliminating the risk to lenders. They also affect the allocation and supply of credit. Loan guarantees thus have direct costs for nonassisted borrowers, in addition to direct benefits for assisted borrowers, but these costs are not reflected in budget outlays.

Guaranteed loans for individuals (such as students), corporations (such as Chrysler), and governments (such as New York City) or direct loans for housing, agriculture, and other purposes share a salient characteristic. They allow the federal government to extend financial assistance while minimizing or even eliminating budgetary costs. Subsidies in the form of direct grants would often serve essentially the same purposes as credit programs, but would have the disadvantage (for political officeholders) of driving up budget totals. Hidden spending allows legislators and executive branch officials to capitalize on the political benefits of distributing assistance while they escape the political costs of raising and financing budgets.

The Growth of Credit Activity

Since the mid-1970s the spending side of the federal budget has risen sharply, from less than $365 billion in fiscal 1976 to over $725 billion in fiscal 1982. Spending growth for this period averaged over 13 percent annually, well above the rate of spending increase during the preceding two decades (see Table 1.1). Spending has also continued to outpace economic growth, rising from an average level of less than 21 percent of gross national product during the 1970s to approximately 23 percent in fiscal years 1980–82.

While the spending budget illustrates the substantial, and growing, impact of federal fiscal activities on the economy, the inclusion of credit activities provides a much fuller and more accurate representation of this relationship. The expansion of federal credit activity has paralleled the remarkable rise in federal spending. By some measures, it has actually been more dramatic.

Measuring Credit Activity

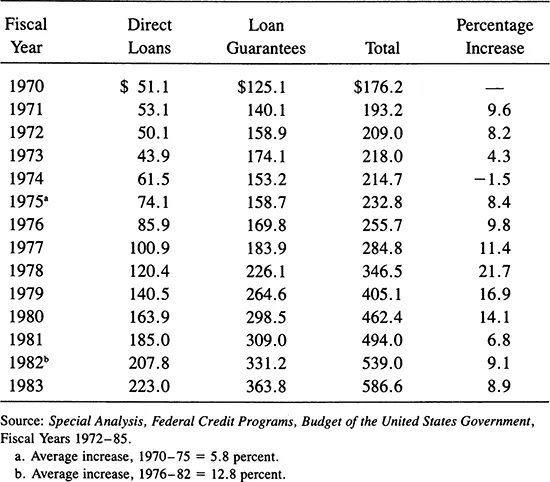

There are various ways to measure federal credit activity. One of the more meaningful is the level of outstanding, or unpaid, loans at the end of a fiscal year. In 1970 this total stood at less than $180 billion, and it rose modestly over the next several years. The growth in credit programs then began to accelerate, resulting in annual increases that averaged almost 13 percent in the level of outstanding direct loans and loan guarantees between 1976 and 1982 (see Table 1.2).

The rapid growth in outstanding loan balances presages problems in the area of government liabilities. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that perhaps 95 percent of outstanding loans will ultimately be repaid, but this is admittedly based upon experience with older, established loan programs.11 Data on defaults for many of the newer programs are limited and inconclusive, but there are indications that default rates may be substantially higher than those experienced in the past. In addition, some of these programs differ from traditional ones in that they are not protected by government claims on marketable property.

Table 1.1 The Growth of Budget Outlays, Fiscal Years 1955–1982

Period | Average Annual Increase (percentage) |

| FY 1955–59 | 5.5 |

| FY 1960–64 | 5.2 |

| FY 1965–69 | 9.3 |

| FY 1970–74 | 7.8 |

| FY 1975–82 | 13.3 |

Source: Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 1984 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1983), p. 9–55.

Table 1.2 Outstanding Federal Loans, Fiscal Years 1970–1982 (in billions of dollars)

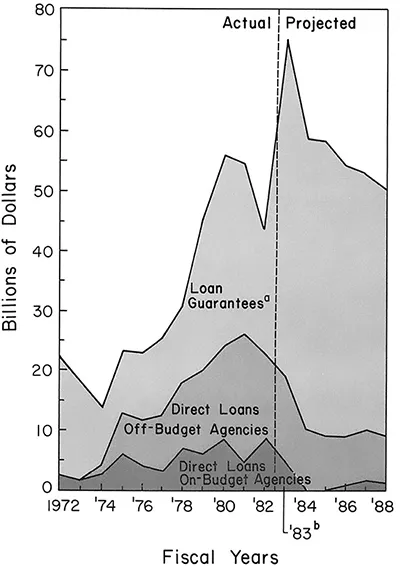

As shown in Figure 1.1, the volume of net federal credit extended each year—new direct loans and loan guarantees minus repayments—roughly tripled between 1972 and 1982, the major increases occurring in off-budget lending and loan guarantees. The budgetary impact of this growth, however, was restricted to the relatively stable net outlays of on-budget agencies.

Moreover, the use of net-lending figures gives a greatly reduced picture of federal credit activity because of the unusual accounting devices utilized by federal agencies. It is perfectly reasonable, for example, to deduct repayments of old loans from new loan commitments in order to measure an agency's net lending during a given fiscal year. These repayments, however, need not be made by the borrowers to whom the loans were extended. Instead, agencies are permitted to “sell” their direct loan obligations to the Federal Financing Bank (FFB).12 When certain agencies sell loan obligations to the FFB, the sales are treated as repayments. On-budget direct loans are converted into off-budget loans, and this conversion allows agencies to add the new funds gained by loan sales to their appropriated funds. In 1981, for example, the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) extended more than $9 billion in new direct loans for its agricultural credit program, but the net outlays for the program showed repayments exceeding new loans by some $900 million. This apparently negative loan activity was misleading, since almost $7 billion in supposed repayments was actually nothing more than the sale of loans to the FFB. The FmHA was repaid for its loans; the government was not. The on-budget loans, however, were now off-budget loans, and the FmHA was able to use its loan asset sales to make new loans. Through loan asset sales to the FFB by the FmHA and other on-budget agencies in 1981, over $14 billion in outlays was removed from budget totals, with a corresponding reduction in the reported unified budget deficit.

The accuracy of net-lending figures is further distorted by the treatment of defaults. In many cases, losses are covered by insurance or reserve accounts, with subsequent transfers to an agency's lending budget. This gives defaults the appearance of repayments in an agency's loan account.13

In order to provide a more accurate picture of program levels, the credit budget format introduced in the fiscal 1981 budget reports gross levels of credit activity. The distinction is a major one. In fiscal years 1980–82, net direct lending averaged less than $25 billion annually (see Table 1.3). (The net lending outlays of on-budget agencies for these years averaged just under $8 billion.) The level of new direct loan obligations, however, was well over $50 billion annually. New guaranteed loans were also several times greater than the net change in outstanding guarantees.

Figure 1.1 Net Federal Credit, Fiscal Years 1972–1988

Source: Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the President's Credit Budget for Fiscal Year 1984 (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, 1983), p. 36.

a. Primary guarantees: excluding secondary guarantees and guaranteed loans acquired by on-and off-budget agencies.

b. Estimate.

The bulk of credit activity, then, is carried on outside the budget reported to the public. The budget is a cash-flow document. It does not show the volume of loan guarantees or the government's growing liability. The direct loan activities of on-budget agencies, which do require outlays, are grossly understated in the budge...