![]()

PART ONE

A MOVEMENT EDUCATION

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Nonviolent Anvil

The encounter was both simple and crude: the white man spit on James Lawson. As divinity student Bernard Lafayette looked on, Lawson, a black minister in his early thirties, asked his assailant for a handkerchief. Momentarily baffled, the young spitter handed him one. Lawson wiped off the spit, handed the handkerchief back, and asked the white man if he had a motorcycle or a hot rod. A motorcycle, the man said. Lawson, tall, gentle, distinguished-looking with black-rimmed glasses, maintained this casual manner, asking technical questions about how the bike had been customized, until the two men appeared simply involved in conversation. Watching in amazement, Lafayette realized that not only had Lawson refused to engage the man on the level of retaliation, but also he had forced his enemy to see him as a human being.

For Lafayette, the performance by Lawson was a revelation: The black minister no longer felt the need to explain to people why he believed in nonviolent action. This was hardly the nonviolence of “begging white folks to accept us.” Lafayette, whose trim frame and open expression belied an iron will, had been raised by devout parents who gave him two pieces of advice seemingly impossible to follow when yoked together: he should always stand up for his rights, and he should avoid trouble with whites. The problem with nonviolence was that not only did it appear weak or unmanly, it also provoked whites. Yet what Lawson demonstrated was as simple as it was transformative: there was no reason to “shout out” that he was doing something as an “act of courage, not an act of fear.”1 Lawson’s gift to Lafayette provided a subtle illustration of how to overcome the contradiction. It was an offering that Lawson would supply to many other potential young activists from the South between 1959 and 1965.

Lawson first learned of nonviolence through the teachings of his mother in the 1930s. When he was ten years old, a small white child called him “nigger” from a car window. Lawson did not hesitate. Possessing little fear of whites, he ran over and slapped the child as hard as he could. Returning home, he recounted the story to his mother. Philane Lawson stood cooking, her back turned to him. When he had finished, she asked, “What good did that do, Jimmy?” He felt “absolute surprise” at her response. “We all love you, Jimmy,” she continued. “And God loves you, and we all believe in you and how good and intelligent you are. We have a good life and you are going to have a good life. I know this Jimmy. With all that love, what harm does that stupid insult do? Jimmy, it’s empty. Just ignorant words from an ignorant child who is gone from your life the moment it was said.” Years later, Lawson recognized the incident as a “sanctification experience,” a moment when his life seemed to stop—and then permanently change. In subsequent decades, whenever he got angry or found himself in a confrontation, he remembered those words: Jimmy, what harm did that stupid insult do? Jimmy, you are loved.2

If his parents got young Lawson off to a promising start, veteran pacifist A. J. Muste and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) proved a vital link to the possibilities of justice on a global scale. Originally an organization formed to support conscientious objectors (COS) during World War I, the FOR had in later years become a major channel for the transmission of Gandhian practices and philosophy to U.S. activists. In his first year at Ohio’s Baldwin-Wallace College in 1950, Lawson heard Muste, FOR’s executive secretary, speak on campus. Lawson joined FOR, and Muste soon became an important mentor.3

FOR’s influence would be evident to Lawson later in 1950, when the Korean War draft board sent him a U.S. Army classification form. Lawson refused to fill out the draft card (a violation of federal law), and soon the army issued a warrant for his arrest. He turned himself in. Undoubtedly he could have qualified for a student, ministerial, or CO’s deferment, but to act on conscience, Lawson felt, one had no moral right to take a deferment.4

Once in prison, Lawson confronted the primary barrier facing all who consider using nonviolent tactics: the almost overwhelming human need to protect one’s own body. He felt most personally challenged by the threat of prison rape. Would he use violence to defend himself? After an agonizing self-examination, he determined that if someone hurt him, he could not control that person’s behavior; his responsibility was to his own conscience. Anything that happened would not ride on personal choice. Rather, it was just “one more thing you have to endure in order to be true to [God]. It is part of the test He set out for you.”5 It would be hard to overestimate the impact of this trial on Lawson—coming as it did years before he began the fateful dialogue with the Nashville students who sustained the sit-ins and the Freedom Rides. That impact was both simple and profound: Lawson’s prison experiences allowed him to relate to the deepest fears of the Nashville students. It was—absolutely—the central challenge each nonviolent practitioner had to face: “How do I respond if someone attacks me or my family?”

After his release from prison in 1953, Lawson left for India to work as a youth minister at a Presbyterian college in Nagpur. While still in college, he had grown wary of work with traditional civil rights groups in the United States. He believed that the NAACP possessed no programs or organizational forms capable of harnessing the growing collective self-respect of black southerners, especially World War II veterans, who were trying to find ways to end segregation in America. Having initially learned about Gandhi through the black press, he had taken a special interest in nonviolence after reading about Gandhi’s 1936 meeting with Howard Thurman, at the time one of the most distinguished ministers in the United States. Thurman asked Gandhi if he had a message for Americans: Gandhi replied that since events in America captured the attention of the rest of the globe, perhaps an African American would succeed where he had failed, by making the practicality of nonviolence visible worldwide. To Lawson, Gandhi’s teachings and actions represented what the Christian God would do if he found himself an Indian subject to British authority or an Afro-American subject to Jim Crow.6

When Lawson heard about the astonishing events unfolding during the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 – 56, he quickly made plans to return home. On meeting the Montgomery movement’s young spokesman, Martin Luther King Jr., in the fall of 1956, Lawson mentioned his experiences in India. He told King that he wanted to work in the South after receiving his doctorate—in about five years. “Don’t wait! Come now!” King said. “We don’t have anyone like you down there. We need you right now. Please don’t delay. Come as quickly as you can.” Lawson understood King’s sense of urgency. Events in the boycott appeared to be happening so fast, no one had time to sit down, converse, and plan where to go next. Few in the movement found it easy to reflect carefully on previous actions. “At best we were all inspired amateurs,” Nashville minister Kelly Miller Smith wrote of this early period. “Much of what had been done had been based on the trial and error method.” Or, as Lawson later explained, “We are becoming teachers when we are still so young that we ought to be nothing but students.” Lawson responded to King’s call at the beginning of 1957, becoming FOR’s field secretary for the South, and set out to canvass the region.7

Lawson began traveling as part of a two-man “reconciliation team” with Glenn E. Smiley, a white minister from Texas and a conscientious objector during World War II. Smiley had brought nonviolent methods to the leaders of the Montgomery bus boycott. Now Smiley and Lawson ran nonviolent workshops throughout the region to show people—experientially—how to act to end segregation. Most workshops, which were sponsored by a church, civil rights organization, or student group on a college campus, lasted two or three days. They started with devotions, songs, and an overview of nonviolence, followed by question-and-answer sessions, break-out groups, and more singing. Then participants engaged in small group discussions and sometimes role-plays.8

James Lawson in Nashville, 1960. Martin Luther King Jr. made it a habit to sit in the first row each time Lawson ran a workshop at SCLC meetings. (Nashville Public Library, The Nashville Room)

Nashville: A Laboratory for Many Montgomerys

Hoping to create a base for nonviolent activism, Lawson moved to Nashville in 1958 and entered Vanderbilt University Divinity School. By this time, veteran civil rights activists had pulled together a new group called the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Martin Luther King Jr. and other African American ministers. SCLC member Kelly Miller Smith, a professor at Nashville’s American Baptist College and pastor of the First Baptist Church in Nashville, encouraged Lawson, making him the social action leader of the local SCLC affiliate, the Nashville Christian Leadership Council. When SCLC began, Smith recalled, the group recognized the need for “a small disciplined group of non-violent volunteers. These persons should receive intense training in spirit technique.” Smith had “no idea how this could be done,” but he believed that SCLC would have to provide the training. Thus, when Lawson arrived in Nashville, Smith immediately asked him to hold workshops in the First Baptist Church on nonviolent philosophy and its applications. Smith was a slightly older minister who had been purposefully laying the groundwork for a civil rights movement. Lawson later described him as dedicated to “social action, social change, and justice.” Smith served as one of the key black players in the city’s cautious efforts at integration over the 1950s. Many regarded the members of his congregation as the black elite of Nashville, and the slow pace of change forced Smith to face “the most seductive pulls which went with his job—public rage and private depression.” In Lawson, he recognized a new spirit that gave him a lift.9

Lawson “intended to make Nashville a laboratory for demonstrating nonviolence.” He wanted “many Montgomerys,” and he thought he knew how to create them. For his idea to flower, he needed people willing to face the same hurdles he had. When Lawson settled in Nashville, he organized a series of workshops that began on 26 March 1958. With Kelly Miller Smith’s support, Lawson worked with ten or so local ministers each week.10

A standout in this group was a student of Smith’s at American Baptist named John Lewis. Lewis, an earnest and devout young man from rural Alabama, drew closer to Lawson because Lawson served as a field secretary for the FOR. Lewis had been impressed by the pamphlet FOR had published a year earlier on King and the Montgomery bus boycott. It explained how nonviolent action could desegregate public facilities in the South. FOR executive secretary Alfred Hassler directed the pamphlet “primarily to Negroes” and aimed to “avoid any indication of hostility toward whites.” He tried to illustrate “the whole struggle in nonviolent, Christian, potentially reconciling terms rather than with violence and bitterness.” The pamphlet—presented in comic book form with vivid graphics and clear examples of the dignity of noncompliance—“wound up being devoured by black college students across the South,” Lewis later explained.11 So when Lawson first offered a workshop under FOR’s sponsorship, Lewis decided that “this is something I should really attend.”12

In the spring of 1959, NCLC took the first step of what Lawson termed a “nonviolent scientific method”—namely, “investigation, research, and focus.” Lay people, including women, joined the group, and together they surveyed the needs of Nashville’s black community. Not only did they target the “white” and “colored” signs, Lawson explained, but they also aimed to “break open job opportunities for people. There were no black cashiers in downtown Nashville. There were no black bank tellers. There were no black secretaries working in corporate offices, there were no black reporters in the two newspapers. There were no black folk in communications.” Except for a few blacks on the council persons, city government was wholly segregated. Though Nashville had a large pool of African American professionals, there were no blacks in the police department hierarchy, in other city services, or on the bench. “Black lawyers had a tough time in the courts because of the abject racism, the segregated restrooms in the courthouse, the lack of reading facilities for black lawyers,” Lawson remembered. Black teachers had only recently won a hard-fought court battle for equal salaries.13

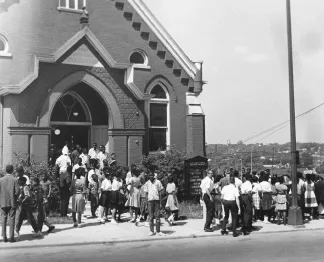

First Baptist Church, Nashville, where Lawson ran nonviolent direct action workshops every Tuesday night throughout 1959. (Nashville Public Library, The Nashville Room)

Life in the workshops signaled the future of the civil rights movement in the South: discussions routinely grew heated and ranged over many subjects—education and segregation of the schools, police brutality and harassment of black people, the segregated job market, and meager job opportunities. In May 1959 NCLC decided to launch a campaign to desegregate downtown Nashville, envisioning a ten- to fifteen-year struggle—“however long it would take.” This created a much larger task than what had been achieved in Montgomery. “Based upon that tenet,” recalled Lawson, “I began to draw up the plan for workshops in September.”14

It was not difficult to recruit students. The word spread through social and church networks that Lawson was developing practical tactics to fight segregation. People flowed in from Fisk University, Tennessee State, Meharry Medical School, Vanderbilt, and American Baptist. “A year earlier we rarely had ten people in that room,” Lewis noted. By the fall of 1959, however, “there were often more than twenty, black and white alike, women as well as men.” Lawson now looked to create a movement “that will involve thousands of people. A public relations man is not our answer. We need [a] program at [the] local level. . . . A wide movement of nonviolence.”15

One of the new recruits was Diane Nash, who quickly emerged as a leader. Intense and poised, Nash, a former beauty queen, had been raised by Mississippi parents who moved to Chicago before her birth. A devout Catholic, she had excelled in the city’s parochial schools before entering Howard University in Washington, D.C.; she then transferred to Fisk. Lewis noticed that she arrived “with a lot of doubt at first.” Nash “came to college to grow and expand, and here I am shut in,” she explained of her reaction to Nashville’s segregation. During her first few days at Fisk, she “learned there was only one movie theater to which Negroes could go. I couldn’t believe it, it took about ten people to convince me.” When she realized that students at Fisk spent most of their time on campus because they could not eat at restaurants or go to most theaters, “I felt chained.” Nash’s status as a beauty queen—light skin, long hair, and light eyes—reflected an attitude widespread among middle-class blacks in the pre – Black Is Beautiful era. Her willingness to walk away from the access her appearance provided to the upper crust of black society indicates her early determination and commitment. She asked around campus, “Who’s trying to change these things?” A friend told her about the workshops. She went.16

Kelly Miller Smith brought some of his most ambitious and intelligent students to Lawson’s workshops, not only Lewis, but also divinity students Bernard Lafayette and James “Jim” Bevel, a veteran raised in rural Mississippi. Lithe, short of stature, and bald, Bevel had what one colleague later described as “the burning eyes and visionary intensity of a Russian mystic. He was always arguing, passionately, some highly original, far-out position.” His hitch in the U.S. Navy proved Bevel to be a rising star: brave, fiercely intelligent, determined to excel. A few years into military service, a chance friendship with an African American cook introduced him to Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You. Bevel left the navy within weeks, persuaded by the novelist’s argument that Christians could not be true to their faith and kill others. A sermon taken from Isaiah convinced him of his calling, and by January 1957 he had saved enough money to enter American Baptist. Lewis, Lafayette, and Bevel would go on to lead major campaigns ...