![]()

Part I

![]()

1: Genesis

The Palestine Conflict to 1945

The Arab-Israeli conflict that emerged after World War II originated in ideological, political, and military developments of preceding decades. When Ottoman authority collapsed during World War I, Britain assumed control of Palestine as a mandate under the League of Nations. The Jews and Arabs of the territory sought political independence, coming into conflict with each other and with Britain. World War II undermined Britain’s ability to govern the mandate and encouraged the Jews and Arabs to fulfill their aspirations through diplomacy and force. Traditionally isolated from the politics of the Middle East, U.S. officials became involved in this dispute as President Franklin D. Roosevelt balanced his personal and political interests against the demands of the Anglo-U.S. wartime alliance.

A brief clarification of terms in is order. Britain called its mandate “Palestine,” derived from the Roman name given the land in A.D. 135. During the mandate, the area’s residents—Arab and Jewish—considered themselves “Palestinians.” “Israel,” the name adopted by the Jewish state in 1948, borrowed from the ancient “Eretz Yisrael” (the Land of Israel), which Anita Shapira calls “a holy term, vague as far as exact boundaries of the territory are concerned but clearly defining ownership.”1 After declaring independence on 15 May 1948, Palestinian Jews called themselves “Israelis.” With the exception of a small number who became citizens of Israel, most Arab Palestinians became refugees from Israel, identified themselves as Palestinians, and called the land they aspired to control “Palestine.” For the sake of simplicity, this book refers to the Arab residents of and refugees from Palestine as “Palestinians,” the Jewish residents of mandatory Palestine as “Jews,” and the Jews of Israel as “Israelis.”

The modern state of Jordan occupies territory that belonged to Britain’s original Palestine mandate. Britain established the territory of “Transjordan” on the land east of the Jordan River, appointed Abdallah ibn-Hussein as its emir in 1921, and granted Transjordan its independence in May 1946, when Abdallah proclaimed the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. U.S. officials referred to the territory as “Transjordan” until June 1949, when the government in Amman convinced the Americans to use “Jordan.” For convenience, this book refers to the territory as “Transjordan” before May 1946 and as “Jordan” thereafter.2

The Zionist-Arab Clash in Palestine to 1945

The modern Arab-Jewish conflict over Palestine originated as a clash of ideologies. Zionism, the dream of Jews to return to their ancient homeland, spawned waves of migration of European Jews to Palestine before World War I. Arab nationalism, by contrast, infused the indigenous inhabitants of Palestine with a burning desire to achieve political independence from foreign rule. To satisfy its imperial ambitions, Britain took responsibility for governing Palestine after World War I. Under Britain’s watch, Zionists and Arab nationalists clashed, with intensifying violence, for control of Palestine.

Although its roots reached to antiquity, “Zionism” emerged as a term and as a political force in Europe in the late nineteenth century. Rising anti-Semitism in Europe, an emerging Jewish identity that transcended nation-state boundaries, and the political activism of Theodor Herzl and others gave birth to a political Zionism that aimed to reestablish a Jewish presence in Palestine. By 1914, some eighty-five thousand European Jews had migrated to Palestine and organized a yishuv, or Jewish community. Their Zionism, which Dan V. Segre defines as a “landless spiritual nationalism,” contained the seeds of the state of Israel.3

The experience of settlement in Palestine transfigured the Jewish community. According to various scholars, the yishuv originally embraced the progressive ideals of social justice and human fraternity and eschewed political and military power. The environment confronting early settlers in Palestine, the spread of militant ideology among a generation of Jews born there, and the dramatic experience of the Holocaust, however, gave rise to an assertive ideology that rationalized political power, force, and domination over Palestinian Arabs.4 Following the linguistic turn in Western academic writing, Nachman Ben-Yehuda and Yael Zerubavel suggest that Israel’s founders exaggerated the heroic aspects of historical episodes to create a mythology that inspired Israelis to fight for their national existence.5

Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion emerged as the most important Zionist leaders of the pre-1945 period. Weizmann, a Russian-born chemist, served as president of the World Zionist Organization (1921–29) and of the Jewish Agency for Palestine (1929–31, 1935–46), in which positions he advanced Zionist goals through diplomacy in London. Ben-Gurion, a Polish-born Zionist who emigrated to Palestine in 1906, established the Labor Party of the Land of Israel as the dominant political party among Palestinian Jews, served as chairman of the executive committee of the Jewish Agency, and otherwise laid the groundwork for Jewish statehood. The two men disagreed about the means to achieve statehood, and Ben-Gurion arranged Weizmann’s 1946 ouster from the World Zionist Organization. But their parallel efforts proved complementary at advancing Zionist ambitions in Palestine.6

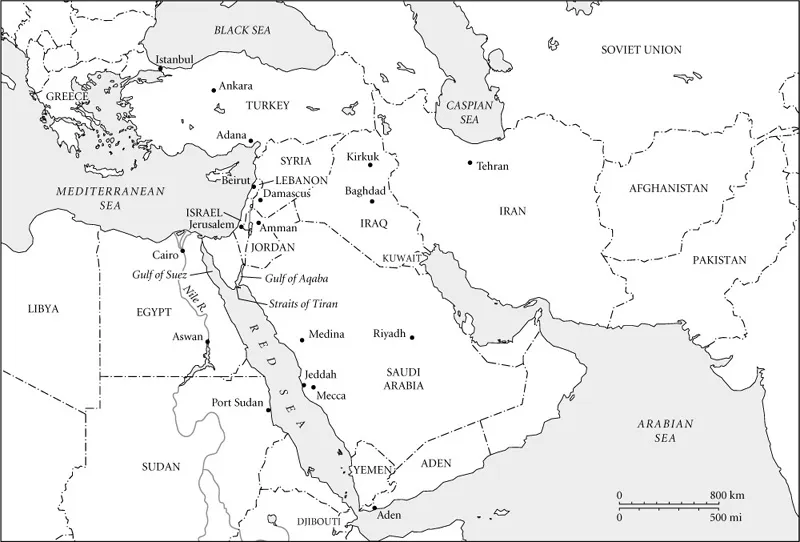

Map 1. The Middle East

Modern Arab nationalism emerged after Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt in 1798 shattered Arab people’s complacency about their subject status under Ottoman rule. Nationalists promoted Islamic reform, territorial patriotism, and pan-Arab identification, Albert Hourani observes, to modernize their societies and escape foreign suppression. Communities in Egypt, Syria, and other Arabic-speaking areas developed a sense of common identity—what Benedict Anderson called “an imagined political community”—based on shared language, culture, and history. According to Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian nationalism blossomed in the early twentieth century as a result of an attachment to Jerusalem, cultural activities, local politics, the Arab Revolt of 1936–39, and opposition to Zionism.7

The seeds of the post–World War II clash between Zionism and Arab nationalism were planted before World War I. To a certain extent, the Zionist and Palestinian Arab communities established patterns of interaction in their daily lives, tried to align their political ambitions and intellectual outlooks, and even considered a partnership to advance their common aims in relation to European imperialism. Yet both communities gradually realized the incompatibility of their national aspirations. By 1914, members of each community predicted conflict between Palestine’s 66,000 Jews and 570,000 Arabs.8

The Ottoman Empire’s loss of control of Palestine and the British conquest of the region during World War I proved to be a catalyst for Arab-Zionist conflict because British statesmen made conflicting agreements and deals with the two sides. In the May 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement, Britain secured French recognition of a British sphere of influence in Palestine. In correspondence with the Hashemite Sharif Hussein of Mecca in 1915–16, the British high commissioner in Cairo, Henry McMahon, implicitly promised British support for Arab independence in Palestine and other areas in exchange for an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire. To serve certain domestic political and diplomatic objectives, Britain also pledged in the November 1917 Balfour Declaration to “view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” Preoccupied by the war in Europe, diplomats in London failed to reconcile these Middle East policies.9

Having issued these conflicting statements about the future of Palestine, Britain secured its hold on the land through war and diplomacy. The capture of Baghdad (March 1917) and that of Jerusalem (December 1917) put Britain in position to demand postwar control of Iraq and Palestine. In autumn 1918, Allied and Arab forces captured Damascus, where Britain allowed Hussein’s son, Faisal, to establish a regime. In 1919–22, Britain secured mandates over Palestine and Iraq, established Transjordan as a separate territory, and recognized Abdallah (Faisal’s brother) as its emir. Britain made Faisal, whom France deposed from Damascus, king of Iraq.10

Britain maintained a prominent position in several Arab states through the end of World War II. It signed a mutual-defense treaty with Iraq in 1930, established air bases in the country at Habbaniya and Shuaiba to protect oil fields and transit routes, officially recognized Iraqi independence in 1933, and bolstered the Iraqi monarchy against indigenous challengers. In Transjordan, Britain nurtured a close political relationship with Emir Abdallah, signed a series of mutual-defense treaties beginning in 1928, and appointed British officers to command the Arab Legion. After signing a mutual-defense treaty with Egypt in 1936, Britain developed a sprawling base complex in the Suez Canal Zone, which by 1945 contained extensive facilities and nearly eighty-four thousand British soldiers.11

In Palestine during the interwar years, British authorities presided over a situation of general stability punctuated by outbursts of violence. Britain preserved a rudimentary stability in the mandate by exercising political, police, and administrative powers. In 1922, it affirmed the right of Jews to reside in Palestine but limited Jewish immigration and pledged not to promote Jewish majority rule or statehood. In exchange for his cooperation, the British allowed the mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husayni, to govern the Palestinian Arab community. Yet the stability of Palestine was repeatedly broken by Arab-Jewish violence. Hundreds of Jews and Palestinians died in hostilities in 1919–21, 1929, and 1933.12

Political tensions erupted in the Arab Revolt of 1936–39. A growing stream of Jewish immigrants to Palestine contributed to a large increase in the Jewish population, which numbered 66,000 (10 percent of the population) in 1920, 170,000 (17 percent) in 1929, and 400,000 (31 percent) in 1936. Convinced that such population changes challenged Palestinian political and economic interests, the Arabs resisted. In 1936, they organized a massive labor strike that triggered rioting and violence against Jews and British officials as well as reprisals by both groups against the Palestinians. British authorities forced al-Husayni into exile, arrested many Palestinian elites for insurrection, and considered partitioning Palestine into an Arab state and a Jewish state.13

In 1939, the threat of world war prompted Britain to formulate a Palestinian policy consistent with Arab interests. Despite the Arab revolt, Britain appeased Arab sensitivities to stabilize Palestine, redeploy its twenty thousand soldiers there, and protect its oil assets and military bases in Arab states. In the White Paper of 1939, Britain strictly limited Jewish immigration to seventy-five thousand persons over five years, scheduled such immigration to terminate in March 1944, and prohibited Jews from purchasing land outside Jewish settlements. Palestinian Arabs would gain gradual control of administrative offices and win statehood within ten years.14

A measure of wartime expediency, the White Paper of 1939 planted the seeds of serious postwar conflict. Jews denounced the document as an unethical and illegal sellout of their vital interests but also realized that they must support the British-led military coalition battling Nazi Germany for control of Europe. “We must help the [British] army as if there were no White Paper,” Ben-Gurion aptly observed, “and we must fight the White Paper as if there were no war.” The yishuv thus refrained from contesting British power in Palestine during the war and sent volunteers to fight in Europe under British command. Yet the Jewish community also routinely violated the White Paper by promoting illegal immigration, and the British responded by denying authorized immigration quotas.15

Britain’s policy toward the Jews became untenable when the Middle East became secure from Nazi attack in 1943. Propartition sentiment revived within Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s wartime cabinet, and increasing militancy among Palestine’s Jews foreshadowed massive postwar resistance to the White Paper. Learning of the Holocaust, British officials realized that to terminate Jewish immigration in March 1944 would be impossible to justify to international public opinion. Churchill grew cold to the idea of helping the Jews, however, after Zionist extremists assassinated his friend, Minister of State Lord Moyne, in Cairo in 1944. Churchill did not change official policy toward Palestine before he departed the prime ministry in summer 1945.16

Despite the terms of the White Paper, the Arabs of Palestine did not thrive politically during World War II. The Palestinian elite remained divided, dispirited, and disorganized, and British bans on political activity before 1943 encouraged political passivity. The exiled Mufti al-Husayni arranged the assassination of his chief Palestinian rival, Fakhri Nashashibi, in Baghdad in 1941, met Adolf Hitler, and offered to collaborate with the Nazis to expel Britain from Palestine. British authorities tolerated al-Husayni but resolved to deny him power in Palestine.17

Surrounding Arab states also took an interest in Palestine. The Arab League devoted its founding conference in Alexandria in September–October 1944 to the issue and demanded that Britain honor the rights of Palestinians. In March 1945, the league called on Britain to fulfill its pledges to establish a Palestinian state. Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt warned of dire consequences to any power that helped establish a Jewish state in Palestine. By 1945, several Arab regimes based their popular support on vigilance in pushing for Palestinian interests. Britain’s inability to broker an internal solution to the Palestine conflict set the stage for the emergence of international conflict after 1945.18

Origins of U.S. Involvement in Palestine

Before World War II, U.S. diplomats paid little attention to the Middle East in general and to Palestine in particular. By the 1930s, some U.S. citizens had begun to press President Roosevelt to endorse Zionism. During World War II, however, government officials identified national security reasons for endorsing Britain’s anti-Zionist policy. As Roosevel...