![]()

ESSAY

“The Great Weight of Responsibility”

The Struggle over History and Memory in Confederate Veteran Magazine

by Steven E. Sodergren

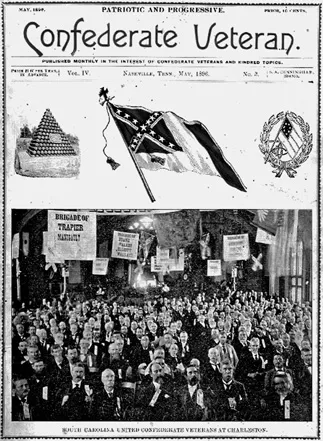

The perspective of history presented in the Confederate Veteran can be seen as one reflecting not only that of the editors and contributors (almost all of whom were also subscribers), but also those of a Confederate veteran community that labeled the magazine its “official organ” by 1905. May 1896 edition, courtesy of Duke University Libraries.

In the July 1900 edition of Confederate Veteran magazine, readers discovered that a “sensation” had occurred at a recent reunion of Union and Confederate veterans. Designated as the “official organ” of the United Confederate Veterans (ucv), the largest veterans’ society in the southern states, it was no surprise that the July edition of the Veteran included details of a veteran’s reunion among its usual collection of soldier narratives and historical editorials. The “sensation” involved comments from a Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic named Albert D. Shaw, a Union veteran and politician who attempted to build upon the feelings of reconciliation at the event. Despite giving a speech described “in the main of excellent spirit,” the Confederate Veteran noted that Commander Shaw “made significant statements with which Southern men will never concur.” Stressing that American schoolchildren should be taught “one idea of American citizenship,” Shaw concluded, “[i]n this view the keeping alive of sectional teachings as to the justice and rights of the cause of the South, in the hearts of the children, is all out of order, unwise, unjust, and utterly opposed to the bond by which the great chieftain Lee solemnly bound the cause of the South in his final surrender.”1

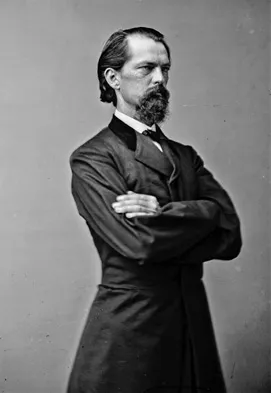

Rising immediately in response to Shaw was General John B. Gordon, Confederate hero, former governor of Georgia, and then Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans. Gordon’s comments were clearly emotional as he proclaimed, “In the name of the future manhood of the South I protest. What are we to teach them? If we cannot teach them that their fathers were right, it follows that these Southern children must be taught that they were wrong. Are we ready for that? For one I am not ready! I never will be ready to have my children taught that I was wrong, or that the cause of my people was unjust and unholy.” The article went on to note that Gordon “spoke as seemed he never did before in a defense of the traditions and principles of the South,” and his speech was printed in its entirety in the July edition of Confederate Veteran, compared to only one paragraph from Shaw’s “sensational” address. (A promise that Shaw’s original speech would be printed in its entirety in the following edition of Confederate Veteran was never fulfilled.)2

Though presented in a theatrical manner, this depiction of how former Confederates viewed the legacy and memory of the Civil War was common in the pages of Confederate Veteran magazine during its nearly forty year publication run from 1893 to 1932. One finds within its pages almost continual repetition of the concept of the “Lost Cause,” first enunciated by journalist Edward Pollard in 1866 as a southern, or Confederate, view of the war. The methods and writings of subsequent “Lost Cause” historians receive appropriately harsh criticism from modern academics; it is not unusual to see their ideas labeled as “sheer craziness” and a “caricature of the truth” in recent literature on the subject. Historian Alan Nolan seems to express the dominant view by claiming that “[t]he victim of the Lost Cause has been history, for which the legend has been substituted in national memory.” As Fred Arthur Bailey has shown, this “legend” served a purpose, providing the means by which southern elites preserved their authority in the region following the war. Other historians have sought to explain why even professional academics in the decades following the Civil War were willing to accept such an intellectually problematic interpretation of the past. Gaines Foster, in his powerful book Ghosts of the Confederacy, lays much of the blame at the feet of academics, stating that while most wanted to be critical of the southern historical view during the formative years of the Lost Cause, they ultimately “failed to live up to their ideal in the face of hostile public opinion.” Yet, while modern historians can repeatedly point out the flaws in the methods and biases behind the Lost Cause interpretation, the question remains why the general public was willing to believe what is today considered such a controversial interpretation of history.3

THE CONFEDERATE VETERAN AND LOST CAUSE HISTORY

The answer reveals not only how southerners interpreted the past and the practice of history following the Civil War, but also illuminates the divide, persistent to this day, in how the public and the academy differ in their approaches to revealing the past. The Confederate Veteran, a periodical that few historians have examined in great detail despite its lengthy run and popularity among southern veterans and their associates, offers illumination on this issue. While the periodical has been mined as a historical source for Lost Cause rhetoric of the Confederate veteran community at the turn of the century, few historians have assessed the distinctive content found within. Instead, the focus tends to fall on works like the Southern Historical Society Papers, which were founded in the late 1870s and heavily influenced by prominent veterans like Jubal Early, a founder and president of the Southern Historical Society. Perhaps the most important element of the Papers was the quasi-academic nature of the publication, which sought “historical authenticity” for its effort at constructing the memory of the Lost Cause. Gary Gallagher accurately notes that other southern periodicals “never approached the Southern Historical Society Papers in terms of influencing historians,” a condition which persists to this day.4

While the historical community may have been swayed by the Papers, certainly the widespread readership of Confederate Veteran demonstrates that it had the greater cultural impact on the southern public. David Blight, in his work Race and Reunion, is one of the few historians who recognizes the impact that the magazine had upon the reading public. He sees the Confederate Veteran, along with veterans groups like the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), as steering the Lost Cause movement by the turn of the century. Blight argues that the Veteran “became the voice of the UCV, the clearinghouse for ‘Lost Cause’ thought, and the vehicle by which ex-Confederates built a powerful memory community that lasted into the 1930s.” The magazine expressed traditional Lost Cause ideas while blending them with a newly forming “reconciliationist vision” of the war that fed into the shifting perspectives of the veterans’ community, no doubt contributing to the magazine’s popularity in those circles. Ultimately, the forty-year run of the Veteran represents a period when southern memory of the war was being molded into a new vision of the past that reconciled some of the inconsistencies that had plagued the Lost Cause for decades. The Veteran contributed to this vision by offering what John Simpson termed “a rich tapestry of Confederate military history for a younger generation of Southerners.”5

Significantly, the Confederate Veteran is representative of not only how its contributors and editors viewed the past, as veterans of the Civil War increasingly passed from the scene at the turn of the twentieth century, but also how those affiliated with the magazine defined such philosophical notions as history, truth, and memory. By examining a selection of approximately fifty pieces from the full run of Confederate Veteran which address the notion of the past in direct fashion (given the content of the magazine, most of its articles do so at least indirectly), one sees a surprisingly self-conscious examination of history. These pieces varied in subject matter, from editorials to soldiers’ accounts of the war to reprinted minutes and speeches from veterans’ gatherings. All found their way into a magazine that reached a peak of 22,000 subscribers by 1902 (at fifty cents an issue). The perspective of history presented in the Veteran can thus be seen as one reflecting not only that of the editors and contributors (almost all of whom were also subscribers), but also those of a Confederate veteran community that labeled the magazine its “official organ” by 1905.6

As General Gordon’s earlier comments indicate, veterans and their associates realized the importance of the past and what effect it would have on future generations. What is surprising is how little these concepts changed over time; other than the inclusion of references to major developments in American affairs over the publication run of Confederate Veteran, the vehemence and structure of how contributors articulated their view of history appeared in 1932 just as they had in 1893. The focus of the magazine would shift from wartime tales and recollections to features on contemporary veteran and memorialization issues with the ascension of UDC member Edith Pope to editor-in-chief following its founder’s death in 1913. However, the Confederate Veteran remained faithful to its original vision and thus sustained its success for another two decades. The contents of the Confederate Veteran were, for the most part, not deliberately manipulated; most soldier narratives and articles on wartime or postwar Confederate activities were written by veterans and their family members trying to get the story right for future generations. That they might fail to accomplish this mission was a possibility that many of those affiliated with the magazine accepted. The goal was not necessarily to find the “truth” in the present, but to provide the source material so that it may be discovered somewhere down the line.7

Confederate Veteran included details of a veteran’s reunion and a speech from a Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic. Rising in response was General John B. Gordon (here, c. 1861), Confederate hero, former governor of Georgia, and then Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans. He proclaimed, “In the name of the future manhood of the South I protest.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

From the very beginning, contributors to the Confederate Veteran stressed the need to settle upon the “truth” before the Confederate generation passed on, recognizing that the future of the “New South” was inextricably linked to the past of the Confederacy. One contributor, Samuel Will John of Alabama, spent an article picking apart relatively minor details regarding the service record of Barksdale’s brigade but concluded, “It may appear to some that these are small errors; but the Veteran will be read by future generations in search of the truth of history made by the armies of the Confederacy, and therefore all who write for its pages should be absolutely accurate in all their statements.” In a report by the United Sons of Confederate Veterans Historical Committee published in the January 1900 edition of the Confederate Veteran, committee members noted the turn of a new century and expressed “the great weight of responsibility that rests upon us” in getting the story of the past right for future generations, adding that “the establishment of the truth is never wrong.” The report continued, “We know that tens of thousands of boys and girls are growing up into manhood and womanhood throughout the South, with improper ideas concerning the struggle between the States, and with distorted conceptions concerning the causes that led up to that tremendous conflict.” Contributors to the Veteran concurred with this feeling of “responsibility” for the future and set out, with apparent good intentions, to make sure that history was properly recorded in the magazine for those who may someday need its lessons.8

Despite this mission of protecting the past for the future, the Confederate Veteran was not designed to be an academic publication, but rather was a periodical aimed at a “mass audience” with the express intent of preserving the past of a deceased nation-state. The magazine was founded in 1893 by Sumner Archibald Cunningham, a dynamic and polarizing journalist who had served in the Army of Tennessee during the war but had seen little real combat. Described by his biographer as possessing an “irritating nature, neuroticism, self-righteous and condescending tones, and defensiveness,” Cunningham ran afoul of several Confederate veterans’ groups in the early 1890s over his alleged mishandling of funds in his role as general agent for the Jefferson Davis Monument Committee. Partly to vindicate himself, Cunningham founded the Veteran to, according to John Simpson, “extricate himself from a potential legal suit” and to salvage his reputation as a spokesman for the Confederate veteran community. In the premier issue, Cunningham in his role as editor portrayed the Veteran as “an organ of communication between Confederate soldiers and those who are interested in their affairs.” Although the first issue focused almost exclusively on the Jefferson Davis Monument fundraising campaign, Cunningham proclaimed that future issues would address “[w]hatever may be desirable to put before representative people of the entire South.” Cunningham apparently tapped into something; the Veteran quickly became the largest southern periodical in the country and made Cunningham “a leading exemplar of the Confederate heritage.”9

THE QUEST FOR TRUTH

With literary contributions from Confederate veterans and their family members, academics, politicians, and the interested public, the Veteran dealt mostly with historical narratives of the war along with the activities and publications of the United Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. As one member of that com...