![]()

Chapter 1

One Reich, One People, One Church!

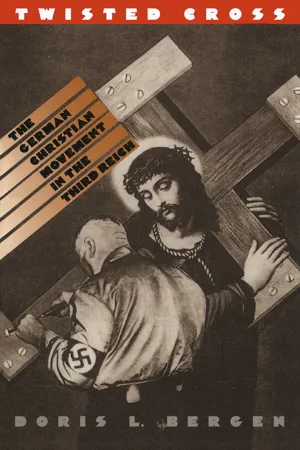

The German Christians

Those who claim to be building the church are, without a doubt, already at work on its destruction; unintentionally and unknowingly, they will construct a temple to idols.

—Dietrich Bonhoeffer

National Socialism, the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer once remarked, “brought an end to the church in Germany.”1 For Bonhoeffer, one of the few Protestant clergymen who took an active role in plans to overthrow the Nazi regime, National Socialist ideology and Christianity were profoundly incompatible. Most Christians in Germany did not share Bonhoeffer’s conviction about the fundamental opposition between those two worldviews, but hard-core Nazi leaders did. Martin Bormann and Heinrich Himmler, as well as Adolf Hitler himself, considered Nazism and Christianity irreconcilable antagonists.

This book is about a group of people who disagreed with both Bonhoeffer and Hitler. Adherents of the German Christian movement (Glaubensbewegung “Deutsche Christen”), most of them Protestant lay people and clergy, regarded the Nazi revolution that began in 1933 as a golden opportunity for Christianity. National Socialism and Christianity, the German Christian movement preached, were not only reconcilable but mutually reinforcing. Along with other Protestants, members of the group expected the National Socialist regime to inspire spiritual awakening and bring the church to what they considered its rightful place at the heart of German society and culture.

Certainly the German Christians, as adherents of the movement called themselves in the 1930s and 1940s, were not unique in their willingness to combine Christianity with other beliefs and traditions. The history of Christianity could be seen as a series of such accommodations and mergers, involving groups as divergent as the Roman imperial elites and the indigenous peoples of the Americas. But the Nazis’ unconcealed, murderous schemes and antagonism toward Christianity might make the attempt to fuse Christian tradition with National Socialism the most improbable combination of all, producing a refiguration barely recognizable as Christian. Advocates of the cause called that outcome German Christianity.

Given the logical and theological contradictions that made up the German Christian movement, it is easy to conclude that it had little influence. Indeed, much of the standard literature on the churches in the Third Reich discounts the German Christians as marginal, soaring to prominence for a brief moment in the wake of Nazi ascension in 1933 but fizzling into obscurity within months.2 The evidence, however, tells a different story. Despite their precarious location between the disapproval of some fellow Protestants on the one hand and the annoyance of the Nazi leadership on the other, the German Christians maintained a significant presence throughout the years of National Socialist rule. For more than a decade, they sustained a mass movement of over half a million members with branches in all parts of Germany. Adherents held important positions within Protestant church governments at every level and occupied influential posts in theological faculties and religious training institutes. From those offices, they controlled many of the decisions and much of the revenue of the Protestant church. The movement’s quest to fuse Christianity and National Socialism reflected the desire of many Germans to retain their religious traditions while supporting the Nazi fatherland. Throughout the 1930s and during the war years, German Christian women and men held rallies, attended church services, and published newspapers, books, and tracts. They sang hymns to Jesus but also to Hitler. They denounced their rivals as disloyal and un-German; they fought for control of local church facilities. Through sermons, speeches, and songs they propagated anti-Jewish Christianity and boosted Nazi racial policy. After the Third Reich collapsed in 1945, instead of being ostracized in their congregations and shut out of ecclesiastical posts, German Christians, lay and clergy, found it relatively easy to reintegrate into Protestant church life.

What beliefs bound the German Christian movement together? How did adherents act out their synthesis of Nazism and Christianity and deal with the glaring contradictions within it? This book explores those questions and offers answers that challenge some standard interpretations. Many scholars dismiss the German Christian movement as merely a Nazi creation. But the German Christians built on theological as well as political foundations, drawing on a legacy of Christian antisemitism and a proclivity to disregard Scripture. Moreover, their fawning enthusiasm for National Socialism notwithstanding, the German Christians did not find themselves consistently within Nazi good graces. Instead, Nazi leaders frequently denounced the movement and resented its attempt to complete National Socialism by combining it with Christianity.

It is also tempting to disregard the German Christians as opportunists, interested in transforming Christianity only to curry favor with Nazi authorities. Evidence of opportunism exists, but it alone does not explain the German Christian movement or account for its tenacity. If the German Christians were opportunists, they were not very shrewd ones. Participation in the movement netted none of its adherents substantial rewards from the hands of top Nazis. After the early days of 1933, it could even have adverse effects. Those whose only interest was to gain the favor of the Nazi leadership generally found it more expeditious to ignore or leave the church rather than try to change it from within.

Finally, one might interpret the German Christian movement as a sincere but misguided mission to rescue Christianity from Nazi assault.3 Many former members took such a stance after the war, arguing that they had wanted only to make Christianity acceptable in National Socialist society. This line of thought might appear to have some credibility in that the German Christians concentrated their energies on the same aspects of Christianity that were most severely attacked by the religion’s Nazi denigrators. Nazi and neopagan critics in Germany reviled Christianity for its Jewish roots, doctrinal rigidity, and enervating, womanish qualities. The German Christians, in turn, focused their efforts on proclaiming an anti-Jewish, antidoctrinal, manly Christianity.

But correlation does not equal causation. Often two phenomena that appear linked as cause and effect are in fact both effects of a common cause. This book will suggest that such was the case with German Christianity and National Socialism. The German Christian movement was not just a product of Nazi orders or a response to neopagan charges against Christianity. Rather, parallels between German Christian thought and Nazi criticisms of it reflect the fact that both grew out of German culture of the post-World War I period. Shared ideas and obsessions about religion, race, and gender linked German Christianity and National Socialism and connected both to broader trends in the society.

If the German Christians were not pawns of National Socialism, craven opportunists, or would-be saviors of Christianity, what were they? I will argue that they were above all church people with their own agenda for transforming Christianity. Although twisted and offensive, German Christian teachings reflected a fairly stable set of beliefs built around a specific understanding of the church. The German Christians intended to build a church that would exclude all those deemed impure and embrace all “true Germans” in a spiritual homeland for the Third Reich. Proponents of the cause called that ecclesiological vision the “people’s church” (Volkskirche), not an assembly of the baptized but an association of “blood” and “race.” In the context of Nazi Germany, that goal had radically destructive implications. And the chauvinistic, antisemitic impulses behind it were anything but marginal.

Definitions and Background

Labels are always tricky, but students of Nazi Germany face particular challenges. To describe National Socialism we depend on the same words and phrases that Nazi propaganda appropriated and infused with particular meanings: words like race, blood, Aryan, German, and Jew. Often authors resort to quotation marks to distance themselves from overtones and associations that they recognize but do not share. I will limit such use of punctuation while maintaining that this entire discussion belongs in quotation marks. We cannot talk about the world of the German Christians without borrowing their vocabulary. But we can keep in mind that use of those terms does not imply validation of that thought.

The problem of labels crops up as soon as we ask, Who were the German Christians? In this book, the phrase German Christians refers only to adherents of the German Christian movement in the 1930s and 1940s, not to any German nationals who professed Christianity. The group’s organizers deliberately chose that name to produce confusion, to force anyone else who claimed both Germanness and Christianity to qualify that identity or risk association with their cause. Members of the group thus used their name to enforce the contention that they represented the only authentic fusion of German ethnicity and Christian faith.

Special problems of terminology arise in dealing with the group of people German Christians described either as “non-Aryan Christians,” “Jewish Christians,” or “baptized Jews.” All three terms referred to converts from Judaism to Christianity or the children, and in some cases grandchildren, of such converts. None of these labels makes any sense outside the context of a social order based on distinctions of blood. I will use the phrase non-Aryan Christian to describe people who, in Nazi Germany, might also have been called Jewish Christians or baptized Jews. The non-Aryan label is humanistically and theologically nonsensical, but historically it is precise enough to be useful because it reflects a category defined by Nazi law with very real consequences for those who fell within it.

Finally, my use of the word Protestant requires clarification. In German, evangelisch is a general label that includes the Lutheran, Reformed, and united churches. Because the English evangelical has very different connotations from the German evangelisch, I have translated evangelisch in its broad usage as Protestant.4

Three main impulses converged to produce the German Christian movement in the early 1930s. Since the late 1920s, two energetic young pastors in Thuringia, Siegfried Leffler and Julius Leutheuser, had been preaching religious renewal along nationalist, völkisch lines.5 Both members of the Nazi party, they called themselves and their followers German Christians. In the summer of 1932, a second group, consisting of politicians, pastors, and lay people, met in Berlin to discuss how to capture the energies of Germany’s Protestant churches for the National Socialist cause. Wilhelm Kube, Gauleiter of Brandenburg and chairman of the National Socialist group in the Prussian Landtag, initiated this effort. Kube’s circle planned to call themselves the Protestant National Socialists, but according to insiders’ accounts, Hitler vetoed that label and suggested “German Christians” instead.6 Followers of Leffler and Leutheuser claimed he had proposed that name to them three years earlier.7 Despite such rivalries, the Thuringian and Berlin groups soon began to cooperate.

A third set of developments fed into the German Christian movement as well. In the 1920s numerous Protestant associations has arisen, dedicated to reviving church life through increased emphasis on German culture and ethnicity. Some of those groups merged with the German Christians; others remained separate but lost members to the new movement or cooperated with it on specific projects.8 That the German Christians did not break away from the established Protestant church eased such interchange.

In July 1933 Protestant church elections across Germany filled a range of positions from parish representatives to senior consistory councillors.9 Representatives of the German Christian movement won two-thirds of the votes cast. Hitler himself had urged election of German Christians, who, he claimed in a radio address, represented the “new” in the church.10 Affirmed by the biggest voter turnout ever in a Protestant church election and soon ensconced in the bishops’ seats of all but three of Germany’s Protestant regional churches, in mid-1933 the movement seemed unstoppable.

Campaigning for the church elections, July 1933, in front of a Berlin church. On the left, the German Christian representative with his sign: “Vote for the German Christian List!” On the right, his opponent from the Gospel and Church group with the placard: “Church Must Remain Church! Vote for the List: Gospel and Church. “ The elections were a triumph for the German Christian movement. (Landesbildstelle, Berlin)

For the next twelve years, despite endemic factionalism, vociferous opposition at home and abroad, and an ambivalent reception from the National Socialist state, the self-styled “storm troopers of Christ” continued to seek a synthesis of Nazi ideology and Protestant tradition and to agitate for a people’s church based on blood. The German Christians represented a cross section of society from every region of the country: women and men, old people and young, pastors, teachers, dentists, railroad workers, housewives, and farmers, even some Catholics. Some occupied powerful positions in the church hierarchy though most were lay members. A few, like Gauleiter Kube, later generalkommissar in White Ruthenia, were prominent in Nazi affairs. Others agitated against certain manifestations of Nazism; Professor Heinrich Odenwald from Heidelberg, for example, was banned from public appearances in 1934 after calling the church to battle against National Socialist excesses.11 All supported National Socialism in some form, however, and many belonged to the Nazi party.

Fragmentation within the movement and the lack of full membership files make it impossible to gauge exact numbers of German Christians at any given time. Adherents of the movement, their opponents in the church, and Nazi authorities generally accepted the figure of six hundred thousand as a reasonable estimate of the group’s numerical strength in the mid-1930s, arguably its weakest phase.12 Despite their diversity, those more than half a million German Christians demonstrated allegiance to a common cause. They endorsed Nazi ideology. They favored German Christian domination of institutionalized Protestant...