![]()

Part One

THE ECONOMIC FRAMEWORK

La filosofia attuale non vuole de’ Locke

e de’ Kant, ma uomini industriosi che

applichino lo spirito alle più elevate

questioni, che in ogni tempo abbiano

interessato l’uomo. I Cockerill sono i

grandi del secolo nostro!

Rivista Europea (1838)

![]()

1

THE RISE OF INDUSTRIALISM

Between the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars and the outbreak of the First World War, Europe underwent a transformation unparalleled in its history. In the course of a century the system of production in industry and agriculture was profoundly altered, the population increased at an unprecedented rate, rapid urbanization shaped a new human environment, the standard of living began to improve dramatically, the relationship between classes and occupations suddenly shifted, learning became accessible to the propertyless, the function of the state expanded from security to welfare, the masses entered political life, economic and social reforms grew and multiplied, the Great Powers rushed into a last spree of imperialist expansion, and the methods of warfare were revolutionized by technological improvements. No comparable change in the way of life had occurred since the prehistoric era, when Neolithic man first mastered the techniques of husbandry, ceasing to be a nomad and becoming a farmer. At the time of the Battle of Waterloo, the prevailing technologies, institutions, and attitudes on the Continent were still those of the preindustrial environment of enlightened despotism in which most men had been born. When the guns of August began to boom some hundred years later, European society had already entered the age of industrialism and individualism, of finance capitalism and mass democracy. A world of new ideals, aspirations, and achievements had emerged.

The key to this transformation was a rationalization of production that came to be known as the industrial revolution. Its essential character was understood almost from the beginning by those who were living through it. In 1835 the Scottish chemist and economist Andrew Ure described the nature of the change in manufacture taking place about him:

The term Factory, in technology, designates the combined operation of many orders of work-people, adult and young, in tending with assiduous skill a system of productive machines continuously impelled by a central power. . . . The principle of the factory system then is, to substitute mechanical science for hand skill, and the partition of a process into its essential constituents, for the division or graduation of labour among artisans. On the handicraft plan, labour more or less skilled, was usually the most expensive element of production . . . but on the automatic plan, skilled labour gets progressively superseded, and will, eventually, be replaced by mere overlookers of machines.1

Ure touched on the two basic elements of the industrial revolution: the mechanization of manufacture and the concentration of labor. They represented an extraordinary breakthrough in the method of production that for the first time made it possible for society to escape the constrictions of a marginal economy. To be sure, the substitution of inanimate for human energy had not been entirely unknown. The windmill and the water mill, the cannon and the sailing ship prove that. But the large-scale employment of machinery in such basic industries as textiles, mining, smelting, and steel making represented a decisive departure from traditional techniques. The introduction of complicated and costly equipment meant in turn that the distribution of labor had to be altered. The division of output among many small manufacturing establishments was possible only as long as tools remained simple and inexpensive. Once the necessary investment in the instruments of production began to exceed the financial capacity of the skilled craftsman, a concentration of the work force in factories occurred that drastically altered the system of manufacture. Thereafter, the master artisan and the handicraft shop were forced into a long retreat before the march of industrialism.

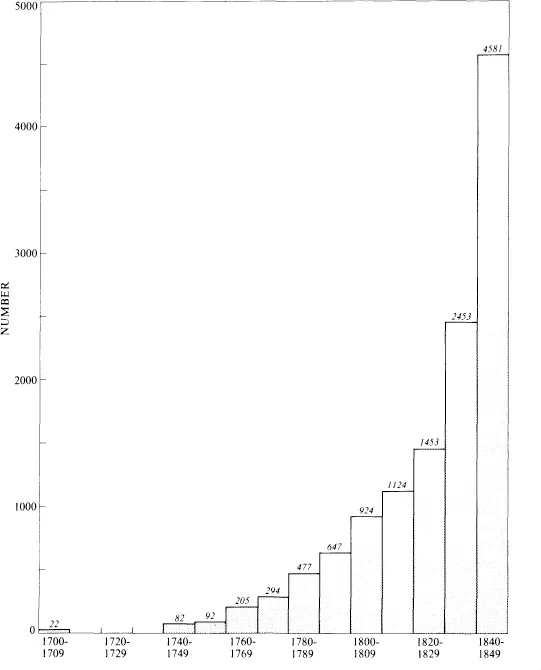

The process of mechanization can be measured in several ways. The number of patents issued in England in the early period of the industrial revolution provides one index of the increasing use of machinery in production (see figure 1.1). In the first half of the eighteenth century, the figures were modest, ranging from twenty-two in 1700—1709 to eighty-two in 1740—49. In the second half, the tempo increased noticeably, although economic rationalization was still in its initial stage. Then, in the nineteenth century, came a flood of technological innovations that dwarfed all previous achievements, reaching 4,581 in 1840—49. In a hundred years the number of discoveries and inventions had multiplied almost fifty times.

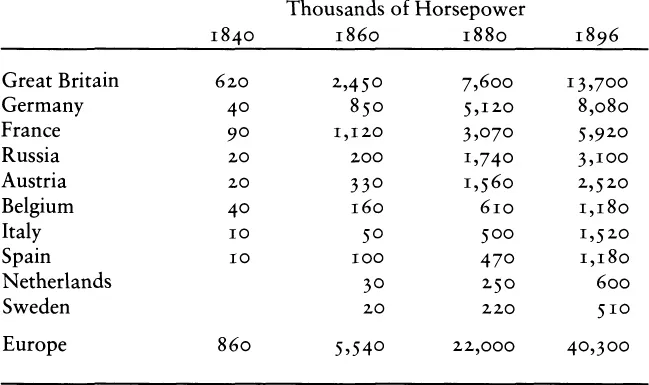

Another rough but useful measure of the degree of mechanization is the capacity of the steam engines employed in production and transportation. Although the figures are only approximate, they unmistakably reflect the growing use of machinery (see table 1.1). In fifty-six years mechanically generated energy increased forty-seven times, a remarkable rate of growth. Every industry felt the effects of mechanization, although its intensity varied considerably. In 1840 Great Britain had 72 percent of the total, but by 1896 only 34. France’s share during the same period increased from 10 to 15 percent. Still more impressive were the gains of Germany, whose horsepower went from 5 to 20 percent of the total. Even small or backward nations experienced a substantial growth. The steady advance of economic rationalization transcended political boundaries and ideological differences dividing the states of the Continent.2

Figure 1.1. Patents Issued in England, 1700—1849

SOURCE: B. R. Mitchell, Abstract of British Historical Statistics (Cambridge, 1962), p. 268.

The concentration of labor was the inevitable accompaniment of the mechanization of production, the two processes providing mutual reinforcement and stimulation. There are no figures for Europe as a whole, but numerous regional studies suggest that a fundamental change in the organization of the work force was taking place. Consider the situation in the Swiss canton of Zürich. In 1827 there were 106 mechanized spinning mills; by 1836 the figure had dropped to 87, and in 1842 there were only 69. The number of spindles, on the other hand, rose from between 180,000 and 200,000 to 293,000 and then to 330,000. In the southeast highland district of the canton, the average number of spindles per spinnery increased from 3,410 in 1836 to 5,499 in 1853 and 8,358 in 1870. Even more pertinent are the data from the Ruhr region of Germany, where, during the early phase of industrialization, the number of collieries grew from 190 in 1850—54 to 241 in 1870—74. By 1880—84, however, there were only 188 collieries, and by 1890—94 there had been a further decrease to 168. The process of concentration then seemed to abate, for in 1900 the figure was 169. Yet the number of workers per colliery was increasing steadily, going from 81 in 1850—54 to 128 in 1860-64, 281 in 1870-74, 470 in 1880-84, 834 in 1890-94, and 1,337 in 1900.

Table 1.1. Capacity of Steam Engines in Europe, 1840-96

SOURCE: David S. Landes, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present (Cambridge, 1969), p. 221.

Statistics for all of Germany reveal that between 1882 and 1895 the percentage of the industrial labor force employed in establishments with five or fewer workers declined from 55.1 to 39.9, and by 1907 it had dropped to 29.5. Those working in establishments with between six and fifty employees increased during the same years from 18.6 percent to 23.8 and 25.0. The largest growth occurred in establishments employing more than fifty workers. Their share rose from 26.3 percent to 36.3 and then 45.5. Even in Russia there was a remarkable concentration of manpower beginning in the 1890s, although it was the result less of natural economic development than of a policy of hothouse industrialization pursued by the government at the urging of the Minister of Finance S. Y. Witte. By 1910 more than half of the factory operatives were in enterprises employing over five hundred workers; in Germany only 8 percent of the industrial labor force was in plants with more than one thousand workers, but in Russia the percentage was 24.3

The direct effect of economic rationalization was a striking increase in the efficiency of manufacture. Between 1870 and 1913 output per man-hour in all sectors of the economy grew at an average annual rate of 1.5 percent in the United Kingdom, 1.8 in France, 2.0 in Belgium, and 2.1 in Germany. These figures reflect only in part the rising productivity of industrial manpower, but more specialized data suggest that factories and mines deserve major credit for the improved performance of the work force as a whole. In the German iron industry, for instance, the average number of workers per blast furnace rose between 1880 and 1910 by 303 percent, from 151 to 458. The average annual production of pig iron per blast furnace, on the other hand, climbed 768 percent, from 19,500 tons to 149,800. In the Russian cotton industry handlooms represented 83 percent of the total number in operation in 1866, but power looms accounted for 62 percent of the output. In England the average daily production of cotton yarn per worker increased from two skeins in 1820 to four in 1840 and eight in 1870, and the average blast furnace, which cast 2 to 3 tons of pig iron a day in 1815, cast 30 to 3 5 in 1865 and 120 in 1878.

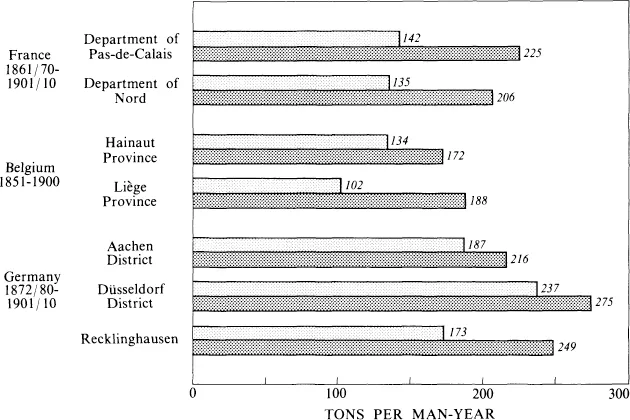

The mining of coal displayed the same tendency toward more efficient production, as the data in figure 1.2 show. Another way of measuring the growing efficiency of industry is the declining cost of labor per unit of production. Thus, the price of a pound of cotton yarn in England included 7.8 pence for wages in 1820, 2.1 in 1860, and only 1.4 in 1880, although the real earnings of an average worker during those years rose about 70 percent.4

Here lies the ultimate significance of the industrial revolution: the ability to expand output without a corresponding increase in the expenditure of human energy. During the nineteenth century the volume of production in all the countries of Europe grew at an unprecedented rate, making possible for the first time a humane balance between supply and demand. Poverty had traditionally been accepted as an inescapable reality of life, because there appeared to be no way in which the economy could satisfy all the material needs of the community. Then, in the decades following the defeat of Napoleon, techniques and technologies began to emerge that made a society of mass consumption attainable. Not that privation as a common experience of mankind disappeared, but a basic transformation in the method of manufacture became apparent that promised to cope with it effectively. The available statistical data trace in detail a dramatic growth throughout the Continent of the output of the basic commodities of industrialization: coal, nonferrous metal ores, nonmetallic minerals, iron ore, pig iron, crude steel, and cotton textiles. Between 1815 and 1913 the volume of industrial production in the United Kingdom multiplied 11 times and in France 5 times. There are no reliable statistics for other European countries in the early decades, but in Germany the volume of industrial production multiplied 10 times during the period 1850—1913, in Russia 11 times during 1860—1913, in Italy 3 times during 1861—1913, in Sweden 7 times during 1862—1913, and in Austria 3.5 times during 1880—1913.5

Economic rationalization became a cornucopia, pouring out an inexhaustible abundance before an astounded Europe. Marc Séguin, a French engineer, reflected in 1839 the sense of exhilaration with which many men regarded the new world being created before their eyes by industrial progress:

The dominant idea of civilized nations today is to increase well-being and the enjoyment of material life. All efforts have turned toward industry, because it is from industry alone that we can expect progress. It is industry which gives birth to and develops new needs in men, and which at the same time gives them the means to satisfy them. Industry has become the life of the peoples [of Europe]. All our wishes, all our talents, all our intelligence should lead toward its development. Superior minds which aspire to the honor of contributing to our social regeneration should rally around this powerful lever.

What are the limits at which human power will stop? Commonplace minds never imagine them to lie beyond their own narrow horizon, and yet every day that horizon broadens, every day those limits are extended. Let us look around us. In the last twenty years the elements of our old civilization have everywhere been modified, perfected, renewed. Everywhere miracles have taken place. The pleasures and conveniences of life which had been reserved for wealth only are now at the disposal of the artisan. A few more steps and they will also be distributed among all classes. A thousand industries, a thousand inventions have been born simultaneously which have brought other discoveries, and these in turn have become or will become the point of departure for new progress. All these changes work to the profit of the public at large, and they tend to make well-being common property. This is a new era, based on love of the good and the beautiful, which is rising on the ruins of class prejudices and the monopolies of wealth.6

Figure 1.2. Efficiency of Coal Production, 1851-1910

SOURCE: E. A. Wrigley, Industrial Growth and Population Change: A Regional Study of the Coalfield Areas of North-West Europe in the Later Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, 1961), pp. 38-39.

There was seemingly no problem that technology could not solve, no obstacle that the machine could not surmount. Mankind appeared to be witnessing the dawn of a new golden age.

The industrial revolution had effects that were felt in every corner of Europe, although its scope and intensity varied from region to region. Generally speaking, it tended to radiate from a center of origin in the British Isles toward the east and the south. For example, by 1816 the amount of coal produced in the United Kingdom already exceeded 15 million tons, but Germany reached that figure only in 1857, France and Belgium in 1872, Austria-Hungary in 1880, Russia in 1900, Spain in 1957, and Italy never reached it. The United Kingdom consumed one hundred thousand tons of raw cotton for the first time in 1830, France in 1860, Germany in 1871, Russia in 1878, Austria-Hungary and Italy in 1890, Belgium in 1911, and Spain in 1915. The United Kingdom first produced 1 million tons of pig iron in 1835, France in 1862, Germany in 1867, Russia in 1891, Austria-Hungary in 1894, Belgium in 1897, Italy in 1939, and Spain in 1958. In the output of crude steel, the United Kingdom passed the million-ton mark in 1879, Germany in 1882, France and Russia in 1896, Austria-Hungary in 1898, Belgium in 1904, Italy in 1915, and Spain in 1929. Each successive measure of the degree of industrialization shows that England was a pioneer, although her lead over her Continental competitors diminished steadily with the growing sophistication of manufacturing technology.

During the 1840s, the well-known German economist Friedrich List portrayed Great Britain as a modern Rome, enjoying a supremacy that “the world has never seen before.” He described as “vain” the efforts of those “who sought to establish their universal domination on armed might alon...