![]()

PART I

Symptoms

![]()

ONE

Barbarism and the Civilizing Sciences

In America, everything that is not European is barbarian.

—JUAN BAUTISTA ALBERDI

Today, the number of unbalanced [individuals] increases due to the erosion suffered by the race in its exhausting attempts to elevate itself to a civilized level.

—FRANCISCO DE VEYGA

Barbarism in a Young and Fertile Country

Argentina, at the tip of South America, was named for the rich silver deposits that European explorers hoped to find there. Its name, in Spanish, meant land of silver, wealth, and money, and like most outposts of empire, the Spanish settlement in Argentina was about profit. Colonial elites wanted to get the most out of Argentina with the smallest input of resources and energy. Standing in the way of profit were the people colonists found there and, in the later centuries, the people whom elites recruited and lured from Europe as immigrants only to label them savages of another kind, equally difficult to control.

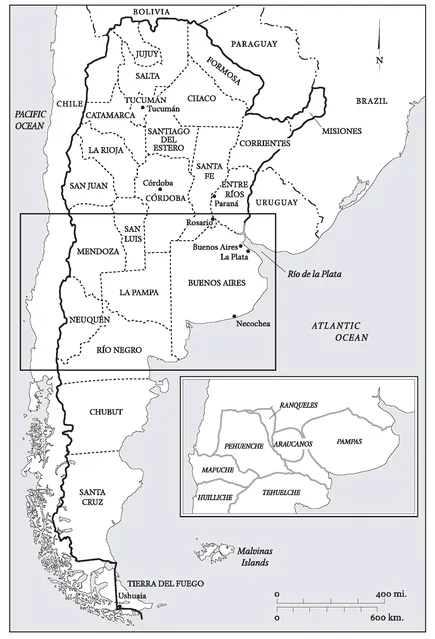

In the fertile River Plate region that became Argentina, the Diaguita, Pampas, Huilliche, Mapuche, and Tehuelche peoples were, for centuries, unconquerable and untamable. Landowners and colonial administrators could not force nomadic “savages” into debt peonage or slave labor or harness their productive forces for tribute, as the conquerors did in Mexico and the Andean viceroyalties.1 The first Spanish expeditions landed in Argentina in 1516, along the Atlantic coastal region, later named the Rio de la Plata (the River Plate), where they encountered the native Querandí. Amerindians killed the first Spanish sailors to set foot on land. Within twenty years, Buenos Aires had been established by a Spanish aristocrat, Pedro de Mendoza, and from this settlement Spanish troops headed north to explore the territory; however, of the twenty-five Spanish settlements established by the end of the sixteenth century more than half were destroyed by Indian raids. Only about 2,000 Spaniards and about twice that number of mestizos, the mixed-race offspring of natives and Spaniards, remained in a land of numerous tribes of Native Americans.

Map 1. Provinces and Territories of Argentina and Native Tribes of the Buenos Aires Region, ca. 1840. (Based on Reginald Lloyd, ed., Impresiones de la República Argentina en el siglo viente, 1911, and Donna J. Guy and Thomas E. Sheridan, eds., Contested Ground: Comparative Frontiers on the Northern and Southern Edges of the Spanish Empire, 1998)

In 1570 there were 1,000 people altogether in Buenos Aires; by 1660 there were 4,000, most mestizo and Spanish, and a few dozen African slaves. Unlike neighboring Brazil and, to a certain extent, Mexico and Peru, Argentina overall had few slaves, but in eighteenth-century colonial Buenos Aires more than 7,000 inhabitants were black, about a third of the population. By 1887, overwhelmed by the wave of European immigrants, Afro-Argentines were less than 2 percent of residents of Buenos Aires, the urban center of the colonial River Plate and a bustling hub of trade.2 In 1776 the River Plate was granted autonomy from Peru within the colonial system and named its own viceroyalty, with Buenos Aires as its capital; by 1810 the population had expanded to 42,000. Exports of cattle hides had grown, and colonial goods from other viceroyalties were being shipped out, along with a lively stream of contraband. The first hospital, orphanage, and theaters had gone up, and new schools (for boys only) were accommodating the growing numbers of creole, that is, native-born, Spaniards.

The terms “uncivilized,” “savage,” and “barbarian” dehumanized and disempowered the conquered and were intended to stigmatize them as inferior, passive, or dangerous. As barbarians they were savages, the dark side of humanity, a threat to the civilized and enlightened, and as such provided a legitimate rationale for conquest, enslavement, and domination. The native Amerindians were seen as a non-European, non-Christian people who must be pacified. The conquerors cited religious and, later, “scientific” texts to back up their claims, equating whiteness of skin and European origin with racial purity and superior culture, habits, and values. After the slave trade to the Americas brought significant numbers of African slaves to Latin America, another meaning of the savage emerged, this time linked to blackness alone.

Argentina’s colonial and postcolonial history of race relations is, in some ways, in strong contrast to that of earlier centers of the Spanish empire like Mexico and Peru. In those large and productive hubs of colonial administration and economy, despite similar violence and subjugation of native peoples, a mythical and romantic view of the ancient civilizations arose.3 Markers and signs of the Incan empire and of native culture, such as monuments, intact Indian villages, and languages, were not destroyed in the onslaught of conquest and survived into the modern period. After the Mexican Revolution ended in 1920, it was official ideology that indigenous and mestizo people, if not the whole nation, were members of a “cosmic race.” In Peru, modern national liberation movements adopted the names and images of Incan predecessors, like the Inca leader Tupac Amaru. In Argentina, by contrast, native people were, literally and figuratively, erased from the national memory.

In mid-nineteenth-century Argentina, as in many other nations, the terms “civilization” and “barbarism” were central, organizing principles of the emerging modern state. They galvanized the first leaders of the newly independent United Provinces of the River Plate, as Argentina was known after independence. Domingo Sarmiento, a national intellectual and later president of the republic, in his classic work Facundo, o civilización i barbarie (Facundo, or civilization and barbarism), published in 1845, memorialized the leitmotif. Sarmiento saw an epic struggle against Argentina’s wild and atavistic forces, represented by the lawless, mixed-race caudillos, local strongmen who ruled the interior regions.4 In the late nineteenth century the federal government required Civilización i barbarie for every Argentine schoolchild. Mid-nineteenth-century state policies, from economic measures to population control, were held up to the standard of civilization over barbarism. Elite descendants of the Spanish ruling classes, especially the large landowners and merchants in Buenos Aires’s port, sought to remold their land into a place of civilization while, at the same time, envisioning Argentina as an advance over Europe’s increasingly crowded and stagnant society. Juan Bautista Alberdi, statesman, diplomat, and author of the Argentine constitution, wrote, “The republics of South America are products and living testimony of the actions of Europe in America. . . . All that is civilized on our soil is European; America itself is a European discovery. . . . In America, everything that is not European is barbarian.”5

With the growth of the cattle industry—the source of about half of Argentina’s exports—a new landed elite had enlarged its power. As trade free of the restrictions of empire became a goal, tensions built between wealthy ranchers and merchants born in Argentina and Spain. In 1806, when the British, engaged in a war that led to Napoleon’s takeover of Spain, occupied Buenos Aires, the Spanish militia was no match for the British force, but creole leaders, white descendants of the Spanish-born, secretly gathered troops from the city’s population and drove the occupiers out within a few months. Throughout the rest of continental Spanish America, too, native-born Spanish Americans were rising up against foreign rule, using the war in Europe as a catalyst to revolution.

Independence, which brought Spanish rule to an end in 1820, had brought also to an end, in theory, three centuries of barbarism. Nonetheless, military success did not end the civil battle. Argentina, like many other emergent Latin American nations, continued to be rocked by decades of violence and struggle. Conflict between elites, and also between the ruling class and the rural and urban masses, created a fractured society.6 Argentine traditionalists sought to maintain the basic structures of the colonial period (now in the hands of the creoles), the feudalistic haciendas (large plantations that ran on highly exploitative labor and debt peonage). The “liberals”—elites of Argentina’s ruling class—looked to foreign models of “progress” in the north Atlantic, especially England and France. They promoted foreign trade, modernized state structures, and new technologies. Provincial elites sought control of local economies, oriented toward the capital Buenos Aires and its port, and sought to turn Argentina outward across the Atlantic, toward the “civilized” world.

Railroads were key to Argentina’s growth and prosperity. A railroad system began operation after 1857 with exports from the provinces: wool, then beef and leather. Interior cities, such as Rosario and Córdoba, grew with the new track lines, financed primarily through infusions of British capital and loans. After 1880, the federal government (with the sanction of Congress) approved hundreds of national concessions and the issuing of other types of permits and passes to foreign companies, such as the Central Argentine Railroad and the Buenos Aires Pacific Railroad, both wholly British-owned, to allow the rapid expansion of the rail infrastructure. By 1890 London had invested £157 million, much of it in railroads, and the miles of track went from 6 in 1857 to 5,800 by 1890. While the British owned most of the track, Argentina’s government elites considered the railroads indispensable because they enabled imports and exports to rise from 37 million gold pesos in 1861, to 104 million by 1880, to 250 million by 1889, and to nearly a billion pesos by 1915.7 Tramways, gas, and electricity systems followed. The city began to fence in tracks, to provide guards at street intersections, and, slowly, to build pedestrian overpasses as well. By 1876, with a telegraph link, Buenos Aires had become the nation’s communications node with Europe and the rest of the Atlantic world. With railway depots outside the city, well-to-do and middle-class city residents built new homes or summer cottages in the suburbs.

The new elite displayed a growing ambivalence about their infant nation. Viewing Argentina as empty but fertile, dynamic, and promising, and despite its emulation and imitation of north Atlantic societies, many of the elite felt superior to other countries, especially other Latin American ones. They pointed to their own spectacular achievements of the late nineteenth century, by which time they had eliminated or dominated their rural rivals. The country was growing wealthy from booming agricultural export trade, especially in beef—a process fueled by immigrant labor and the infusion of British capital—inspiring the European saying, “rich as an Argentine.” After New York City, Buenos Aires had become the next largest city on the entire Atlantic seaboard. The nation’s population skyrocketed from 1.1 million in 1857 to 3.3 million in 1890; most of this growth occurred in the large cities of the littoral or coastal region. Wealthy residents and the federal government financed a succession of beautification projects, including grand buildings, boulevards, parks, and public works. With the help of European capital and German and British architects, Buenos Aires leaders had refashioned a former colonial village into the “Paris of South America.”8

But Argentina, a young and fertile country only recently freed from colonialism, and with its native people having been exterminated by force, was seen by the elite as empty and in need of a new population. Juan A. Alsina, a public health physician with the immigration service, lamented in 1898, “Of the 2,885,620 square kilometers that make up the surface of the Argentine Republic, there are hardly inhabitants in proportion of 1.40 per kilometer. That is a vacuum!”9 Santiago Vaca-Guzmán, Bolivia’s foreign minister and literary figure who lived in Argentina, wrote that same year that the “imbalance between the means of subsistence and the number of inhabitants” in Argentina might provide an outlet for Europe’s own “excess of population.”10 By combining its rich natural resources, European tools, and the right kind of immigration, Argentina might exceed other countries, and not only in Latin America, and achieve parity with wealthy industrial countries to the north.

Civilizing the Pampa: Transcending the Nation’s Past

In the context of a conflict-ridden and chaotic postcolonial Argentina, elites struggled for dominance of the natural resources in the River Plate region. After 1880, a group of liberal modernizers, politicians, scientists, and intellectuals known as the “Generation of 1880” responded by eliminating the remaining native people, the cowboys of the plains or gauchos, and the rural caudillos, who stuck to the land and their own ways. Military incursions in the 1880s into previously impassable territories in the Pampas region and in the extreme north and south were sometimes accompanied by naturalists and anthropologists seeking data on the inhabitants and cultures of the interior regions. One such study in 1881, by Luis Jorge Fontana, a young government official in the Chaco, a northern region that until then had been an “Indian land,” surveyed not only the region’s landscape but its native peoples, even as armed forces were wiping them out or driving them to the margins of the nation. President Nicolás Avellaneda credited Fontana’s book El gran Chaco (The great Chaco) with infusing the nation with a “scientific spirit.” The author, Avellaneda wrote, “belongs to the small group of youths who, opening a new way in the intellectual history of our country, have resolved to attempt study and exploration. . . . All these works begin to give a new aspect to our intellectual development.”11 It was a perspective that would come to characterize the governing elite for the next decades, that science was a partner of government and often justified its practices.

Fontana’s book included a chapter on the native inhabitants’ “intelligence,” which was accompanied by a chart of measurements of their heads and feet. Although Fontana challenged the assumptions of “European authors” who “assign a very diminished amount of intellectual faculty” to Indians, he concluded that the Chaco Indians were “more intelligent, cooperative, and above all, more obedient than the Indians of the Pampa and Patagonia”; the southern natives were more bellicose because of their freezing cold environment and thus could “never be as intelligent and able to learn.” The Araucans of the Pampa thus exhibited “primitive” behavior.12 Fontana’s stance and tone of racial superiority would pervade much Argentine social and scientific thought for decades to come.

At the same time, a rising young general named Julio Argentino Roca led troops against the natives, considered obstacles to the nation’s progress, in one of the most decisive battles of Argentina’s history. In just under a year, his forces slaughtered native people, shuttling a few to designated reservations, in what was known as the “conquest of the desert.” The land was far from a desert, its pampas the country’s richest and most productive farm-land. Highly profitable cattle, wheat, and sheep trades would be established there. To Roca, who represented the wealthy elite, it was a desert culturally, void of industry and European settlers, and populated by nomadic and unproductive people.13

Also targeted for extermination were the gauchos, who were independent of large landowners and had often sided with the natives or with local strongmen, known throughout Latin America as caudillos. Roughriding cattlemen, many gauchos were of mixed race, a few were Jewish immigrants. The Buenos Aires elite regarded all gauchos and caudillos with contempt. They considered the gauchos to be unmodern and racially and culturally barbaric. Ironically, once the gauchos had been eliminated, they began to be romanticized by poets and writers and, eventually, came to symbolize the new nationalist idea of the “true” Argentine national character (see chapter 9). Today the gaucho, as a legend, is one of the best-known symbols of Argentine culture.

The caudillos, from the small-time local demagogues to regional leaders with armies of their own, a legacy of the decentralized colonial control, were in the eyes of the late nineteenth-century modernizers an even more formidable threat to national progress than the gauchos. The caudillos’ influence had been consolidated in many regions by civil strife and anarchy in the decades after Argentina’s independence in the early nineteen...