This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

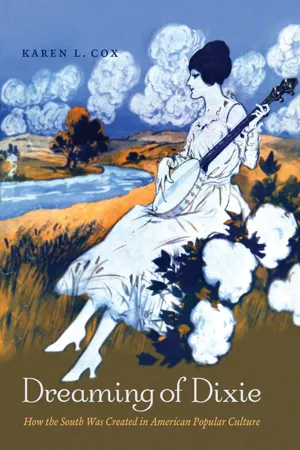

From the late nineteenth century through World War II, popular culture portrayed the American South as a region ensconced in its antebellum past, draped in moonlight and magnolias, and represented by such southern icons as the mammy, the belle, the chivalrous planter, white-columned mansions, and even bolls of cotton. In Dreaming of Dixie, Karen Cox shows that the chief purveyors of nostalgia for the Old South were outsiders of the region, playing to consumers' anxiety about modernity by marketing the South as a region still dedicated to America's pastoral traditions. In addition, Cox examines how southerners themselves embraced the imaginary romance of the region's past.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Dreaming of Dixie by Karen L. Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Popular Culture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 Dixie in Popular Song

Jack Yellen, a Jewish immigrant to the United States from Poland, was an unlikely person to write songs about the American South. His family immigrated to Buffalo, New York, in 1897 when Yellen was five years old. He went to college at the University of Michigan and returned to Buffalo to work as a journalist. He enjoyed writing songs on the side, and though he had never visited the South, he wrote lyrics to some of the most popular songs about the region to come out of New York’s Tin Pan Alley—the center of music publishing in the early twentieth century. As Yellen recalled, “Dixie songs were then the craze, and like all other writers of our limited talents . . . we started out by imitating.”1

Yellen achieved his greatest fame for the songs “Happy Days Are Here Again” (1929) and “Ain’t She Sweet” (1927), but his early success as a lyricist was with the songs “All Aboard for Dixieland” (1913) and “Are You from Dixie?” (1915). During the early twentieth century, hundreds of songs about Dixie that became popular American music were not written by southerners or even Americans who had spent time in the South. Tin Pan Alley’s composers were primarily first- and second-generation Jewish immigrants who lived in New York, had never traveled below the Mason-Dixon Line, and did not have the faintest idea what the region was like. Yet they wrote reams of songs about Dixie that became popular music during the years leading up to and beyond World War I and which later had a renaissance on early radio and in movies.

The music that emerged from Tin Pan Alley often focused on romantic themes and exotic places. When the focus was on the South, the region symbolized a place where people living in hectic urban environments like New York or Chicago could psychologically escape. More famously, Irving Berlin and George Gershwin joined Yellen and numerous other song men of Tin Pan Alley to write songs about the pastoral and preindustrial South—a region that was distinct from the rest of the country and yet distinctly American.2 The South served as the place where many Americans believed that the rural ideal could still be achieved, and songs about Dixie perpetuated that ideal through plantation images of the region—a trend that was also taking place in books about the South and in the advertising of consumer goods.3

It did not matter that the sentimental South they wrote about was mythological—through their songs, Tin Pan Alley musicians, lyricists, and composers helped sustain a familiar image of the region most Americans identified as southern. Moreover, it was an image they readily consumed when they purchased sheet music, which sold by the millions. Songs about the South contrasted sharply with the urban environment where Yellen and others plied their trade. Certainly, Tin Pan Alley publishers had enormous success with sentimental ballads of all types, but the theme of Dixie proved particularly profitable. In 1930, Isaac Goldberg, an early documentarian of Tin Pan Alley, commented on this trend, offering his own explanation for why the South provided northern composers with lyrical inspiration. “Paradise is never where we are,” he wrote. “The South has become our Never-never Land—the symbol of the Land where the lotus blooms and dreams come true.” The fact that the region had been destroyed by war and that a life of leisure was one perpetuated by slavery seemed inconsequential. More important, songs about Dixie sold well.4

This nostalgia for the South was part of a long development in the history of American popular music that stretched back to the minstrel stage of the 1840s. Popular music of any era generally offers a reflection on American character and culture at specific points in time, and from the days of minstrelsy through the heyday of Tin Pan Alley, popular songs about the South consistently perpetuated an image of the region as primitive, exotic, and pastoral. Throughout most of the nineteenth century, nostalgic songs with southern themes were born out of the minstrel tradition on stage and in songs that emphasized an idyllic and monolithic South. This tradition remained strong into the twentieth century as minstrel songs continued to be performed on the vaudeville stage and, later, on early radio. Between 1890 and 1920, sales of sheet music about Dixie soared into the millions thanks to the expansion of the music publishing industry in New York. Throughout this period, songs about Dixie never strayed far from themes of a romanticized South. As Isaac Goldberg suggested, the South served as inspiration for songwriters who saw a paradise in mythological Dixie, regardless of whether it matched reality.5

Tin Pan Alley’s song men built on the legacy of nineteenth-century American composers who wrote what were known as “Ethiopian” or minstrel songs—the most famous of which were the plantation melodies by Stephen Foster but also those of Daniel Decatur Emmett. Foster’s “Old Folks at Home” (1851), also known as “Swanee River,” and Emmett’s “Dixie’s Land” (1859), better known as “Dixie,” became instantly popular with American audiences and were the forebears of a song tradition centered on the theme of the plantation South. Significantly, the most successful popular songs about the region from the mid-nineteenth century through the early twentieth century—from Stephen Foster’s compositions to those of Irving Berlin—were written and published by northerners and were extremely popular with northern audiences, which shared the composers’ nostalgia for the South and sentimentalized its race relations. As an 1861 editorial, entitled “Songs for the South,” explained, Emmett’s “Dixie’s Land” was, “like most articles of Southern consumption . . . imported from the North—Northern men perpetrating both words and music.” However, the reality was that nonsoutherners were even larger consumers of southern songs then and for years to come.6

Stephen Foster and Daniel Decatur Emmett were among the progenitors of a tradition of northerners who wrote songs about an idyllic South. Foster was born in Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, and Emmett was from Mount Vernon, Ohio. Foster is considered America’s first major composer and certainly had considerably more success than Emmett. But both composers attained their greatest success as writers of minstrel songs. Emmett was important to the development of American minstrelsy and founded the Virginia Minstrels in 1843. He wrote “Dixie’s Land” for the Bryant Minstrels while living in New York. The tune was intended as a “walk around,” the closing number performed in a minstrel show, and it swiftly became popular throughout the country. It appealed to America’s nostalgia for the antebellum South and was an upbeat song that was easy to sing. Although not intended as a rallying song for southern armies, it nonetheless became associated with the Confederacy, even though numerous other writers of the period composed different lyrics for the song, including northern versions such as “Dixie for the Union” and “Dixie Unionized.” More than fifty years later, a writer for Outlook magazine commented on how “Dixie” was still “the most popular patriotic song in this country,” in part because “the Northern people like the Southern people,” suggesting that although the song was fixed in the American imagination as a southern tune it was still admired by the rest of the nation. Its lyrics, however, make clear Emmett’s effort to capitalize on the sentimental appeal of a preindustrial South—“I wish I was in the land ob cotton,/Old times dar am not forgotten”—incorporating the theme of a black man who longs to return “home” to the plantation where he was most happy, a popular theme in minstrel songs as the issue of slavery became increasingly divisive and the nation headed toward civil war.7

Foster’s impact on American popular music was more far-reaching than Emmett’s, and his compositions are credited with helping to shape American identity both within and outside of the United States. Only twenty of his two hundred songs were influenced by the minstrel tradition, but his blackface dialect songs have had the longest impact on American music and are the best remembered. The song “Old Folks at Home,” better known as “Swanee River,” is arguably his most famous. The tune, about the Suwanee River in Florida, a place Foster never visited, has been performed and recorded by countless artists and has influenced some of the most highly regarded composers of the twentieth century. Irving Berlin’s first hit, “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” (1911), paid homage to “Swanee River”; George Gershwin’s first hit song was “Swanee” (1919); and Duke Ellington composed “Swanee River Rhapsody” (1930).

Foster’s song was originally sold and performed as a “plantation melody,” owing to its dialect. During the nineteenth century, the Christy Minstrels—the nation’s best-known minstrel troupe—helped to popularize the song. New York music publisher Firth, Pond & Company, which published Foster’s song, as well as “Dixie” and numerous other minstrel tunes, had difficulty keeping up with the demand for the sheet music for “Old Folks at Home.” In twentieth-century parlance, the song was a “hit.” The lyrics capitalized on northern sentimentality toward southern blacks, employed dialect, and were nostalgic for the antebellum South, as the line “Still longing for the old plantation,” suggests. Foster initially did not want his name linked with the song because of its association with minstrelsy, yet the song’s success inspired him to write to Edwin Christy in 1852 requesting that his name be reinstated to the piece. According to Foster, he decided to “pursue the Ethiopian business without fear or shame” after all and sought to “establish [his] name as the best Ethiopian song writer.”8

Indeed, Foster went on to write more songs in the minstrel tradition, including the tune “Old Black Joe,” published in 1860. It tells the story of a former slave who is being called by his departed friends “from the cotton fields” when his “heart was young and gay,” employing the common trope of a minstrel song in which a black man, presumably now living in the North, longs for the time when he lived on a plantation and worked alongside his friends. For decades, several lyricists incorporated the line “the land of Old Black Joe” into their own minstrel songs as a way of linking their compositions to the American South, and the song has had enormous longevity as popular American music. During the 1930s, the Sinclair Minstrels, made up of four white men, performed the song as the opening number of their radio program in Chicago, some seventy-five years after its publication, and “Old Black Joe” has been recorded by Tommy Dorsey and more modern artists from Jerry Lee Lewis to Van Morrison.9

Foster’s songs became popular because they were appreciated by a cross section of the American public; their appeal traversed regional, ethnic, and class lines. Moreover, printing technology by the mid-nineteenth century made it possible to reach a mass audience. Indeed, it was the improvement in this technology, combined with advertising, that eventually made sheet music a commodity available to Americans across the country, and the sale of sheet music became the litmus test by which songs became popular music. Music swiftly became a profitable commodity in the late nineteenth century, and in 1887, Ticknor & Company of Boston reissued Foster’s songs “My Old Kentucky Home” and “Swanee River” in a “full gilt” publication. The book was illustrated with a “typical Southern mansion,” “the possum and the coon,” “the field where sugar canes grow . . . and other pathetic scenes and incidents of the old slave life in Dixie.” Such fare sold very well among American consumers, who enjoyed Foster’s music and whose image of the South was not far removed from such illustrations.10

By the mid-1890s, New York City had the greatest concentration of song publishers in the country, and it was during that decade that a new genre of popular song, also linked to the American South, took the country by storm—the “coon song.”11 Throughout the nineteenth century, most minstrel songs were written and performed by whites, who caricatured blacks to comedic effect for white audiences, most especially as “Zip Coon” and “Jim Crow.” “Zip Coon” was the urban black dandy, very often living in a northern city, who tried to emulate white dress and manners. As played on the minstrel stage, the clothes were loud and flashy, and the character often mangled the English language. “Jim Crow” was portrayed as a plantation Negro who spoke slowly, shuffled his feet, and wore tattered clothing. Both figures were firmly entrenched in the American imagination by the time of the Civil War, and during the second half of the nineteenth century this ensemble of minstrel figures expanded to include the greedy, money-hungry, black woman. Beginning in the 1880s, all three figures appeared on the vaudeville stage in performances of this new genre known as coon songs, which were much more vicious in their portrayals of blacks.12

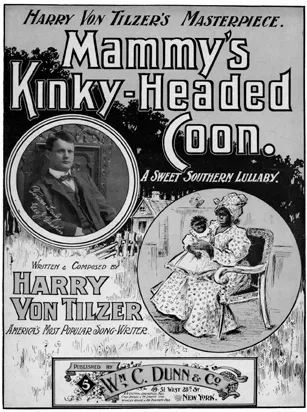

“Mammy’s Kinky-Headed Coon,” sheet music cover, 1899. (Courtesy Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana)

The term “coon” was not used to describe blacks until the 1880s and can be attributed to the popularity of coon songs, which became a trend in music publishing that lasted through the first decade of the twentieth century. Whites associated southern blacks with eating raccoons, and in coon songs they also became known as chicken-thieving, watermelon-eating, razor-wielding oafs. These tunes were enormously popular in the decade of the 1890s, not surprisingly during the period of heightened racial violence nationally. In that decade, over 600 coon songs were produced as sheet music and performed in music halls and vaudeville shows around the country. In effect, coon songs expressed American racism and were important to popularizing black stereotypes. Such music also supported the rise of the music publishing industry in New York, which profited handsomely from their sale. These songs, as expressions of the larger culture, played a unique role in perpetuating Jim Crow racism across the country. Their lyrics made fun of blacks and kept alive racist stereotypes often associated with the South; however, such stereotypes were held more broadly in American culture, which was what made them profitable to the music publishers of Tin Pan Alley.13

Ironically, many coon songs were written and performed by blacks. Sam Lucas, Ernest Hogan, and even Paul Laurence Dunbar—best known for his dialect poetry—wrote lyrics for coon songs. Hogan’s “All Coons Look Alike to Me” (1896) was the first song of its type to become a big hit. Published in 1896 by M. Witmark & Sons, the song stereotypes a black woman as only having an interest in men with money and black men as “coons” who are indistinguishable from one another:

All coons look alike to me, I’ve got another beau, you see

And he’s just as good to me as you, nig! Ever tried to be

He spends his money free, I know we can’t agree

So I don’t like you no how, All coons look alike to me.14

It is well documented that Hogan later regretted writing the song, as African Americans generally resented co...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dreaming of Dixie

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1 Dixie in Popular Song

- CHAPTER 2 Selling Dixie

- CHAPTER 3 Dixie on Early Radio

- CHAPTER 4 Dixie on Film

- CHAPTER 5 Dixie in Literature

- CHAPTER 6 Welcome to Dixie

- EPILOGUE

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX