![]()

Chapter 1

The Tragedy of the North Carolina Indians

Herbert R. Paschal

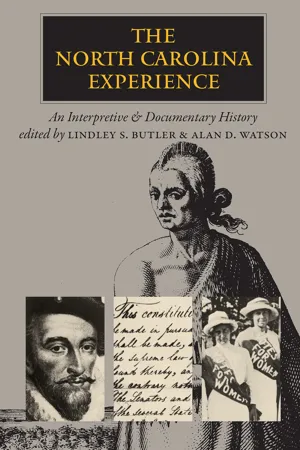

Old Man of Pomeiock, by John White, 1585, engraving by Theodore De Bry, 1590 (Courtesy of the Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, N.C.)

The study of the American Indian in North Carolina has proceeded at two levels. One of these has had as its principal goal the description of the Indians’ origins and culture, social and political organizations, and manner of life at the time of their first encounter with Europeans. The second level of study has centered upon the interaction between the Indians and the Old World intruders.

The confrontation between Indians and Europeans holds out to the historian many possible topics for exploration, but there is one that transcends all others—the rapid disintegration of the Indians’ way of life and their virtual disappearance from North Carolina after the arrival of the European settlers. Loss, therefore, is the central theme of North Carolina Indian history. The astonishing rate of attrition suffered by the Indians of North Carolina dwarfs all other aspects of their history. Only a clear understanding of the tragic details of this story can lead to a full appreciation of the Indians’ role in North Carolina history. Before turning to explore this theme, however, we need briefly to note the origins of the first inhabitants of the American continent and to describe the Indians in North Carolina at the time of permanent European settlement.

The Indians who peopled North America were descendants of the Asian hunters who gradually pushed westward from Siberia over the Bering land bridge into Alaska probably between twenty-eight thousand and twenty thousand years ago. By 9000 to 8500 B.C. the aborigines had reached and begun to settle in small numbers in the region that would someday be North Carolina. These earliest arrivals belong to the Late Paleo—Indian period. They were nomadic hunters who moved about in small bands hunting the giant bison, mastodons, mammoths, and other great mammals, using spears tipped with a distinctive stone point known as the Clovis Fluted.

Upon the appearance of the Archaic period, dated 7000 to 6000 B.C., the economy of the Paleo-Indian peoples of this region changed noticeably. They gradually came to depend on small game, fish and shellfish, and wild plants for their food sources. Although the variety of tools increased, the spear continued to be the chief weapon of the hunters, but it was now used with a spear thrower or atlatl to give it greater distance. Altogether, the Archaic period can be viewed in the words of Peter Farb as “a long period of time during which local environments were skillfully exploited in a multitude of ways.”

Sometime about 700 to 500 B.C. the Woodland period evolved. This period was characterized by the appearance and development of pottery, the beginnings and growth of agriculture, and the replacement of the spear by the bow and arrow as the chief weapon of the hunter. The Woodland period passed through a number of increasingly complex stages, and by historical times well-developed and highly diversified societies were occupying the land that would become North Carolina.

The Indians in North Carolina entered the historical period early in the sixteenth century with the arrival of European explorers along the coast. The earliest visitors to North Carolina found the Indian a fascinating element in the New World scene and were soon sending reports describing these people and their physical characteristics, dwellings, villages, manner of life, religion, government, and society back to an entranced Europe. As European discovery and exploration gave way to European settlements, descriptions of the Indians and comments upon them came more and more to express two sharply divergent views about the Indians’ nature and character.

To many observers the Indian was a noble savage living without guile or the conceits of more advanced societies and finding in the forces of nature and the wilderness about him spiritual strength and direction. Others saw the Indians as brutal and bloodthirsty, devoid of even the most limited attributes of civilization, and unwilling or unable to master them. Obviously the truth lies somewhere between these two extremes, but which point of view is to be given the greater credence is difficult to determine. Recent scholarship has leaned heavily toward the concept of the Indian as nature’s child while assigning his European protagonist the role of the brutal interloper.

The first permanent settlers of North Carolina found nearly thirty Indian tribes living within its borders. They ranged in size from a few hundred persons to several thousand. Although each tribe spoke a different language, each of the languages belonged to one of three linguistic groups. That is, each tribe spoke a tongue that belonged to either the Algonquian, Iroquoian, or Siouan linguistic families.

The Algonquians in the mid-seventeenth century were represented in North Carolina by nine to ten tribes. They lived in an area extending from the Virginia border southward to about Bogue Inlet and from the Outer Banks westward to an imaginary line running along the west side of the Chowan River through present-day Plymouth, Washington, and New Bern, and on to the ocean near Bogue Inlet. The tribes living in this area in the mid-seventeenth century were the Pasquotank, Yeopim, Poteskeet, Chowanoc, Machapunga, Bay or Bear River, Pamptico, Hatteras, Neusioc, and possibly the Coree. These tribes were the most southerly of all the Algonquian linguistic groups. Tribes speaking an Algonquian-related tongue occupied the entire Atlantic seaboard from coastal North Carolina northward into Canada.

Archaeological research in North Carolina has identified cultural materials produced by the Algonquians as beginning about A.D. 800 to 900. The region that would become North Carolina lay within the gray zone between the northeastern and southeastern cultural areas, so it is not strange that the culture of the Algonquian tribes and most other North Carolina tribes contained elements from both regions. The impact of southeastern culture traits was, however, less obvious upon the Algonquians than upon any other groups in North Carolina.

The Algonquian tribes, with the exception of the Siouan Cape Fear Indians, were the only tribes in North Carolina to have any sustained contact with the European intruders in the sixteenth century. (Document 1.1) Contact that began in the 1520s reached a climax in the 1580s, when English colonists sent out by Sir Walter Raleigh made several efforts to establish themselves on Roanoke Island. The abortive settlements on Roanoke Island were productive of several accounts of the coastal Algonquian as well as watercolor studies of these Indians and their way of life by the artist John White.

The Algonquian tribes lived in villages of about ten to thirty houses. Some of the villages were palisaded, and some were clusters of houses surrounded by open fields. The houses were rectangular, usually thirty-six to forty-eight feet in length, with barrel roofs, which early explorers likened to an English arbor. The basic frame was formed by saplings lashed together and covered by bark or reed mats.

Corn was the principal agricultural crop of the Algonquians although pumpkins, beans, and other crops were grown. Fishing and shellfishing were of major importance, as is clearly indicated by temporary fishing campsites and vast piles of oyster shells. The Indians concentrated upon those pursuits primarily in the spring, before corn could be harvested. Hunting with bow and arrow and gathering nuts and berries were also crucial to the Algonquian diet.

The scarcity of stone in the coastal area limited its use among the Algonquians, who relied chiefly on wood, bone, and shell for their tools and utensils. Coils of clay were shaped into pots and fired to make them hard. The basal portion of these pots was typically globular in form.

Religion was important to the Algonquians, who worshiped a large number of gods and spirits, many of them found in the forces of nature. They erected anthropomorphic idols to represent their gods and believed in an afterlife for all.

The three Iroquoian-speaking Indian tribes living in whole or in part in North Carolina at the time of European settlement were the Cherokee, Tuscarora, and Meherrin. The Cherokee occupied both sides of the southern Appalachian chain and claimed a hunting range of forty thousand square miles of wilderness, a vast region that included the entire mountain area of North Carolina. Their towns were located in three different geographical areas, and the inhabitants of each area spoke a different one of the three principal dialects of the Cherokee language. These three groupings of the Cherokee villages were known as the Lower Towns, the Middle Towns, and the Overhill or Western Towns. The Middle Towns were located along the rivers of western North Carolina and spoke the Kituwah dialect.

The Cherokee, according to linguistic analysis, broke away from the original north Iroquoian center about thirty-five hundred to thirty-eight hundred years ago. Although there is no proof that they moved into the southern Appalachian region at this time, archaeological evidence discovered over the past quarter of a century has increasingly indicated that there has been a long and unbroken occupation of that area by the Cherokee. The period of Cherokee occupancy of the southern Appalachians, which can be supported by archaeological evidence, has been variously estimated at one to two thousand years.

Earliest Cherokee population figures date from the first decades of the eighteenth century and vary widely. The most likely estimates fall between sixteen and twenty thousand persons living in sixty to sixty-four towns and villages. Located in the river valleys of their mountainous land, the towns were often strung along bottom lands of the rivers for miles with the dwelling houses scattered among the fields of corn, squash, pumpkins, and beans. Houses were square or rectangular in shape and composed of a framework of poles covered with bark or woven siding. The roofs were made of bark or wood. Clay or earth was often tamped into the sides of the houses in a wattle-and-daub construction.

Many of the Cherokee towns had a flat-topped earthen mound near their center on which a ceremonial or town house was built. This house was constructed by the town and was usually larger than the ordinary dwelling. Its roof was thatched with rushes. Here guests were entertained, council meetings were held, and ceremonial events were carried out. (Document 1.2) The Cherokees were excellent farmers, although like all North Carolina Indians they relied heavily upon game for their food. The gathering of roots, nuts, and berries and fishing added to their diet.

The Tuscarora, who derived from the same Iroquoian linguistic center to the northward as did the Cherokee, are estimated on the basis of linguistics to have broken away from the main northern trunk from nineteen hundred to twenty-four hundred years ago. When precisely they thrust themselves into the North Carolina coastal plain is not known. The events and circumstances of the historical period indicate a surprisingly close relationship between the Tuscarora and the most important Iroquoian group to the northward, the Five Nations of New York. At the same time, relations between the Tuscarora and the Cherokee were always bitterly hostile.

Although accurate early population figures are lacking, the Tuscarora apparently numbered about five thousand persons in the seventeenth century and lived in about fifteen villages lying chiefly between the Tar and Neuse rivers, especially along Contentnea Creek and its tributaries. The warlike character of these people was early noted by explorers and affirmed by their Indian neighbors. The emphasis on village autonomy that characterized their political organization has led some writers to insist that the Tuscarora nation was a confederation of tribes, but recent studies have shown that this was not the case.

The villages of the Tuscarora fall into two general categories. The most common was the rural village or plantation, which was composed of several clusters of three or four cabins surrounded by cultivated fields and scattered over an area of several miles. The other form of village consisted of a number of habitations surrounded by a palisade made of upright logs. The houses were bark-covered and circular in design, resembling beehives, though the rectangular barrel roof structures made familiar by the Algonquians were also used by the Tuscarora. Agriculture was important to the Tuscarora, although hunting and gathering remained an essential part of the tribe’s life.

The Meherrin Indians lived principally in Virginia along the river of that name and were tributary to that government, but they asserted control over some lands on the North Carolina side of the border. In the eighteenth century, under pressure from the Virginia government and settlers, the main body of the tribe moved southward into the less populated area of Carolina below the border. In 1669 they were reported to have fifty fighting men in two villages.

The Siouan-speaking tribes of North Carolina held the piedmont region between the Tuscarora and the Cherokee and occupied the Cape Fear River valley to the sea. Linguistically the North Carolina Sioux were related not only to the Siouan tribes of the Virginia piedmont and South Carolina but also to the powerful Sioux of the Dakotas and the Great Plains. Because of the migratory habits of many of the piedmont Siouan tribes, it is difficult to determine whether certain of these tribes ever settled permanently in North Carolina. At least some of the villages of the following Siouan tribes were located in North Carolina at one time or another: Cape Fear, Catawba, Keyauwee, Saponi, Eno, Tutelo, Sissipahaw, Occaneechi, Shakori, Sugeree, Waccamaw, Woccon, Waxhaw, Saura or Cheraw, and Adshusheer.

Except for the Catawba, who numbered about five to six thousand, most of these tribes were small. The villages of the Sioux consisted of round, domed houses all of which were encircled by a palisade. There was a heavy reliance upon hunting and gathering, although crops of corn, beans, and squash added considerably to their diet. (Document 1.3) When Europeans began to enter the Siouan country they found these tribes living in great anxiety and fear because they were being subjected to constant raids by war parties from the Five Nations of New York. In an effort to avoid these fierce raiders from the north the Sioux began to move about and shift their village locations so that they could be less easily located.

The frantic movements of the Sioux as they sought to avoid destruction were portents of the future for the nearly thirty tribes of North Carolina. Forces more powerful than the dreaded Iroquoian raiding parties confronted all of the tribes as European settlers began to push southward from Virginia. As a result, the Indian all but vanished from the borders of North Carolina.

Warfare between Indians and settlers and between one group of Indians and another sharply reduced and, on occasion, virtually destroyed a number of tribes in North Carolina. Although the losses sustained in pitched battle were debilitating to the tribes, of at least equal importance was the destruction of their supplies, villages, and crops. Because each tribe lived almost entirely upon its own resources, the destruction of its food and instruments of production could lead to starvation and death. The prominence of agriculture among the North Carolina tribes made them even more vulnerable because the increased availability of foodstuffs had led to a population growth that could not be sustained by hunting and gathering alone. Unlike the settlers, the Indians had no system of credit or avenues of trade by which they could replenish a destroyed food supply.

The first significant conflict between Indians and settlers in North Carolina pitted the Chowanoc against the Albemarle settlers in a two-year war that ended in 1677 with the defeat of the Indians. Thereafter relative peace reigned for three decades, though the numerous Tuscarora and smaller tribes were sufficiently powerful to restrict white settlement to the eastern coastal area from the Albemarle to Pamlico Sound.

Early in the eighteenth century white expansionist efforts, represented particularly by the New Bern settlement of 1710, the enslavement of Indians, and continued “sharp” trading practices by settlers provoked the Tuscarora and their allied tribes to a full-scale assault upon North Carolina settlements. The Tuscarora War would have been devastating but for the timely assistance rendered by two South Carolina expeditions, led by John Barnwell and James Moore respectively, which resulted in the complete defeat of the Indians by 1715. Most of the Tuscarora subsequently migrated northward to join the Iroquois in New York; the remainder settled upon a reservation laid out for them in present-day Bertie County. (Document 1.4)

With the decline of the coastal tribes only the Cherokee in the west stood in the path of white expansion in North Carolina. Coinciding with the French and Indian War in the 1750s was the appearance of white settlers in the foothills of the Appalachians, and the French seized upon Cherokee apprehensions to gain the Indians’ ...