![]()

1: Introduction

Hitler remained an eternal adolescent:

gauche, sprung from modest circumstances,

never at ease in his polished shoes.

—Saul Friedländer

A whole generation of Germans born in the first third of this century became identified with Adolf Hitler in one way or another. Thousands were absorbed by his dynamic movement before 1933, and millions joined his party after he became chancellor. Additional millions involved themselves to a greater or lesser degree in the multifarious activities of more than two dozen party affiliates, auxiliaries, and more loosely associated organizations. In a broad sense, all Germans were affected by the Nazi movement between 1933 and 1945, even though their thoughts and daily lives may not have been entirely determined by official ideology and policy. Those for whom the latter might have been true were to be found in the inner core of political functionaries and in the prominent party formations. For some 10 million young members of this generation—between the ages of ten and eighteen at the beginning of World War II—Adolf Hitler held a special identity, since the organization to which they belonged had adopted his name as their own. Whether they joined freely or by force of law, whether they believed fully in the Führer’s cause or merely said they did because everyone else seemed to say so, whether they actively promoted nazism or actively resisted it, they were all members of the Hitler Youth generation.1

From the start of his political career in Munich after World War I to the final bizarre moments in his Berlin bunker, Hitler was obsessed with youth as a political force in history.2 He expressed it dramatically to Hermann Rauschning in 1933: “I am beginning with the young. We older ones are used up. … We are rotten to the marrow. We have no unrestrained instincts left. We are cowardly and sentimental. We are bearing the burden of a humiliating past, and have in our blood the dull recollection of serfdom and servility. But my magnificent youngsters! Are there finer ones anywhere in the world? Look at these young men and boys! What material! With them I can make a new world.” He went on to draw a stark and primitive picture of “a violently active, dominating, intrepid, brutal youth” from which he rightfully thought the world would “shrink back.”3

Most of Hitler’s boys never reached the “ripe manhood” he thought would result when his inhumane prescriptions were implemented. Millions of Hitler’s children learned how to die before they had learned how to live. For the survivors disillusionment, despair, and deprivation became the harvest of a generation. It was expressed poignantly by one member of this generation, Wolfgang Borchert: “We are a generation without adhesion and without depth. Our depth is an abyss. We are the generation without happiness, without home and without farewell. Our sun is small, our love cruel, and our youth is without youth. We are the generation without boundary, without restraint and protection—expelled from the orbit of childhood into a world prepared by those who despise us. They gave us no God who could have captured our hearts when the winds of this world swirled about us. So we are the generation without God, for we are the generation without an anchor, without a past, without recognition.”4

Few of Borchert’s cohorts have told their stories in print.5 The collective experience of his generation as such has not been written because the sources are sparse and the concept of historical generation lacks precision.6 Since the Hitlerjugend (HJ) was not an independent organization, it must be understood in the context of national socialism as a movement composed of various functional segments or affiliates. The structural complexity of this movement and the inhuman deeds perpetrated in its name have produced a literature so vast and a diversity of interpretation so diffuse that no consensus is in sight.7 If there is agreement on any one characteristic, it must be that it was youthful in its origins and remained so, in relative terms, to the end.8

The social, political, and military resiliency of the Third Reich is inconceivable without the HJ. It was the incubator that maintained the political system by replenishing the ranks of the dominant party and preventing the growth of mass opposition. It may be impossible to define the influence millions of young people had on parents, teachers, and adults in general, but there can be little doubt that the uniformed army of teenagers had something to do with promoting the myth of Hitler’s invincible genius.9 When the war began, the importance of the HJ as the cradle of an aggressive army became apparent to military leaders and to the creators of the combat wing of the SS.

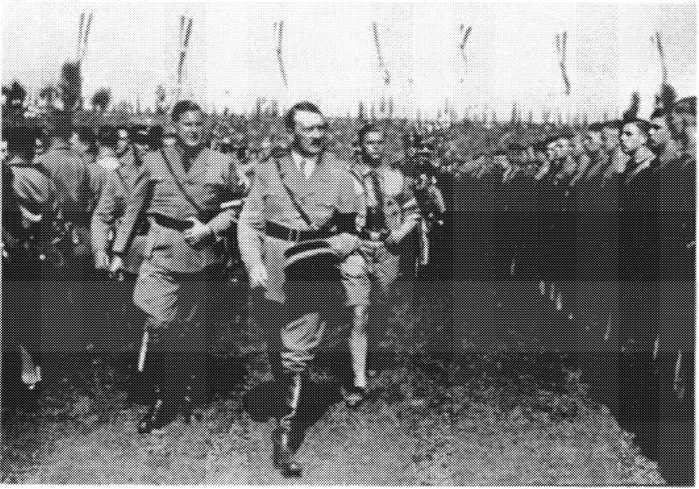

Hitler and Schirach inspect the HJ at the Nuremberg Party Rally, 1934 (Bundesarchiv Koblenz)

Because the functionary corps tended to ossify after 1933, the party itself lost influence. Yet millions of politically reliable leaders functioned within the hierarchical corps of the party and within the affiliates and auxiliaries through which society was encompassed, if not entirely controlled. Maintenance of this ruling elite was dependent on the HJ in a substantial way. Since the party exercised its power not by instructing the state but by superseding normal governmental functions, the mobilization, indoctrination, and control of youth became an important factor.10 It may be true that the youthful members of the movement were not particularly interested in careers as party functionaries during the middle 1930s.11 What has been overlooked, however, is the development of a close relationship between the HJ and the SS precisely at that time. This collaboration provided the leaders of the HJ with new and more attractive career possibilities. The most dedicated members of the HJ preferred the equally young and dynamic SS over the party’s aging and lethargic political cadre. The function of the HJ in maintaining Nazi domination did not depend on transfer to the political cadre, but was exercised in the broader context of the movement, particularly its association with Himmler’s SS, the most pervasive affiliate in terms of influence and power.

Recent statistical analysis suggests that the age factor was indeed significant. Both members and leaders in the early party were even younger than had previously been intimated—in their twenties before 1925—and on the whole younger than the Reich population between 1925 and 1932. There was a change in the situation after the establishment of the regime, despite efforts to reverse a familiar institutional phenomenon, which in the case of national socialism meant the average age rose to the middle and late forties by 1942–43.12 This suggests the lack of a consistent pattern of rejuvenation, and once again points to a different avenue for the expression of youthful energy. As the fulcrum of power changed to the SS, so did the career drift of the young and ambitious.

In this context, then, the SS becomes the other crucial factor in the equation. Organization and indoctrination without systematic terror could hardly have sufficed to keep the movement in power and the war in being. It would have succumbed to grumbling, dissent, and opposition.13 The regime has been described as a “leadership-state” with an elaborately mythologized Führer dominating both state and party. The SS in this system functioned as a kind of “Führer’s executive,” becoming in the process the “real and essential instrument of the Führer’s authority.”14 As a tool of domination and destruction the SS has long attracted attention. Among students of the SS, Robert Koehl has now ripped off the “mask of possession” and revealed a banal and frightening reality in the world of the “Black Corps.” He too was first to note a special relationship between the HJ and the SS. This generational alliance between key affiliates has been ignored.15

This investigation then seeks to enlarge our picture of the Nazi movement by exploring the institutional and social processes through which the SS manipulated and exploited the HJ in order to facilitate the supply of personnel for its numerous programs, tasks, and functions. The historically significant implications of these structural processes become evident when the social and psychological effects on the young people involved in them are incorporated in the analysis. In this way new perspectives can be gained on national socialist institutions, on Nazi society, and on the interrelationship of generations in the Third Reich. In a highly structured society like that of Germany under Hitler, it is logical to select those programs and organizational arrangements where this interrelationship can be exposed in a direct and realistic way, in the mundane contingencies of everyday life. While recruitment of soldiers was at the heart of the HJ-SS alliance, I have chosen to concentrate on aspects which involve social control, economic and agrarian policy, demographic engineering, and physical fitness programs. Ultimately, the intergenerational alliance found its consummation on the battlefield, of course, and most poignantly so on the peculiar field of a “children’s crusade” during the twilight of the Third Reich.

Beginning as a movement of youth, the Nazi party after 1933 became all things to all men. In an era of crisis it could pass itself off as a revolutionary movement, but the outcome of its policies and programs was anything but progressive—at least not by calculated intent. Once the NSDAP had attained power, its proclaimed programs were frequently ignored, and even its organizational statutes were repeatedly circumvented. Titles, roles, and jurisdictions were mixed, duplicated, and deliberately confounded. The structure and function of the party changed with the moods of its distant charismatic leader and his self-willed derivative agents. It was more polycratic than monolithic in nature. Retrospectively, one can find evidence of technocratic efficiency and social engineering, utter personal loyalty and pervasive conflict, ancient barbarism and modern social welfare, full productive employment and squandered natural and human resources.16

How could any political party contain these diverse elements and channel the various political and ideological objectives? The answers to this question have been debated and discussed for half a century.17 Now this lengthy discourse has entered a new phase, and a concerted effort is being made to revise the nearly unanimously accepted hypothesis that in terms of its electoral base the NSDAP was a lower-middle-class phenomenon and hence a kind of petit bourgeois revolution. Systematic analysis of leaders and rank-and-file members and sophisticated use of multivariate regression analysis of the social basis of electoral support have fueled the debate about the origins of national socialism. It now appears that the electoral constituency and the class composition of the membership was much broader and more diverse than previously assumed. Some have gone so far as to discount the prominence of youth in the movement before the seizure of power, and some are even tempted in part to bid “farewell to class analysis.”18 This study seeks to demonstrate the utility of the communal ideal as an instrument of social integration in the context of the intergenerational everyday realities of the Third Reich. It carries the revisionist interpretation a step further by showing how the party—newly become regime—sought to turn a much-touted but relatively unstable popular movement into an instrument by which German society could become a genuine Volksgemeinschaft transcending class and creed. The preferred agents in this attempted transformation were the HJ and SS.

Although his conclusions about Hitler’s “social revolution” have undergone considerable criticism,19 some of David Schoenbaum’s pointed questions still have productive relevance. “How important was a minister, a diplomat, a party functionary, a Labor Front functionary, a Hitler Youth leader, a member of an Ordensburg?” he asked and found no answer. The Third Reich, Schoenbaum believed, “was a world of general perplexity in which, even before the war, ‘Nazi’ and ‘German’ merged indistinctly but inseparably, and the Volksgemeinschaft of official ideology acquired a bizarre reality.”20 Martin Broszat found evidence of a functioning communal ideal even earlier, as a consequence of World War I. He saw significance in “the socialisation of millions of soldiers from different classes, denominations and provinces within an army under the national flag.”21 More recently Broszat has returned to the theme. Staking out a middle ground in the continuing Schoenbaum debate, he emphasizes the importance of the Nazi appeal to the ideal of a classless community, especially among the young masses of the movement.22

In the middle of this debate is the “new” school of Alltagsgeschichte.23 Thus far this kind of scholarship has tended to concentrate on day-to-day experiences, attitudes, and moods of individuals and small groups, largely of the working class. Underlying continuities and persistence of traditional social and moral values have been emphasized.24 Consequently, the effect of the Volksgemeinschaft in bringing about a kind of social revolution—or even the mere perception of one—has tended to be denied, deemphasized, or pictured as a false goal, used merely as a manipulative tool of continuing elitist domination, extending to the persistent class structure of modern industrial society in Germany and other Western countries. Some argue that working-class solidarity was maintained under Hitler,25 but most contend that there was more dissent, resistance, and opposition on the lowest level of society than had previously been allowed. Potential revolt, so the argument goes, was merely neutralized and postponed by a combination of guile, force, and deceptive image-building, through the propaganda media and dramatic political staging. Two important results flow from this type of social history. One is that a bridge between academically restricted scholarship and the general reading public is being built. The other has to do with the youth factor, particularly the function of the Hitler Youth in the Nazi regime, which is finally receiving the attention it deserves.26

The appeal to a “national community,” especially for the young, was a factor in the attainment of power and expressed itself particularly well through the party affiliates. The party per se lost influence in major military and political decisions during the war. Army leaders and civil administrators became important elements in the structure, because their expertise was indispensable, and because most of them shared the Volksgemeinschaft ideal with the Nazis, if for their own particular social and political reasons.27 The SA, SS, and HJ, along with other affiliates and auxiliaries, were needed to seize power and to sustain domination. It is particularly in the relationship between the party and its affiliates, and among the affiliates themselves, that fruitful new lines of inquiry into the realities of the system are to be found.

From a purely organizational point of view, fundamental distinctions can be made among three separate elements of the movement, perceived as such. There was, first of all, the political leadership itself, hierarchically structured, beginning with block leaders and capped by the Führer’s deputy, but ...