![]()

chapter 1 The Simmons Machine

The new era of North Carolina politics formally began on a crisp, clear January day in 1901 amid 1,500 tromping soldiers in broad-brimmed hats and leggings, blaring bands, and a sea of flags and bunting. Stepping off a special train that took him from his home in Goldsboro to his new residence in Raleigh was Charles Brantley Aycock, a forty-one-year-old attorney and the newly elected governor. A carriage pulled by four plumed white horses carried Aycock and his family from the station to the Capitol. Crowds lined Martin and Fayetteville Streets to catch a sight of the new governor, with cheering men doffing their hats and women waving their handkerchiefs as he passed by. Atop a bunting-draped platform on the east side of the Capitol, Aycock took the oath of office. An old man held up a white supremacy banner and a young boy held a white rooster, the symbol of the Democratic Party. Small boys sat on the second-floor balcony, their legs dangling over the edge. A band played “Dixie.”

This was no ordinary inauguration, but the fruits of what Aycock called a “revolution.” North Carolina had been “redeemed” for the Democratic Party and for whites—just as it had been in 1877 when federal troops withdrew, ending the period of Reconstruction. The populists were for all practical purposes dead. The Republicans were to be vanquished from power for generations. Blacks were no longer a factor. And white Democrats were beginning seventy-two years of uninterrupted rule in North Carolina. The political mold was cast for most of the twentieth century.

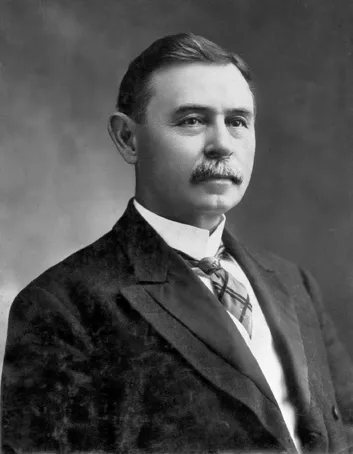

Aycock was the man of the hour. But the man behind the new governor was Furnifold McLendel Simmons, a forty-seven-year-old New Bern attorney who for the next thirty years would be a U.S. senator and a political figure so powerful that the state’s Democratic organization would become known as the Simmons Machine. Simmons not only held the seat longer than any North Carolinian had ever held it before, but he also exerted a powerful political influence back home. Only once in his thirty years of influence was his choice for governor defeated, and Simmons corrected that “error” by politically destroying the man who had the temerity to buck his machine. The list of his political lieutenants who he helped put in the governor’s mansion is a long one: Aycock, Robert Glenn, Locke Craige, Cameron Morrison, and Angus McLean. Even O. Max Gardner, who would later found his own political dynasty, could not get elected governor until he made his peace with the old man.

Simmons controlled state politics with a potent organization that extended into every rural crossroads and mill village. He had a keen sense of what motivated voters, often engaging in raw racial demagoguery. And according to his contemporaries, he and his political operatives had few qualms about stealing an election if necessary. “The record of Simmons’s career makes one of the saltiest chapters in the history of American politics,” wrote journalist W. J. Cash.1

The bridle of one-party rule had been forcefully put on the state. The question of race, as far as the Democratic leadership was concerned, was a settled question: African Americans were to be second-class citizens. But North Carolina’s dueling impulses were also evident during the early decades of the century. The Simmons Machine was a ruthless, antireform organization that loved to thump the Bible in public but had few reservations about stealing an election behind closed doors. It reflected the social conservatism of the countryside: North Carolina should be run for the benefit of whites only, women shouldn’t bother their little heads over voting, liquor was the devil’s tool, and Catholics couldn’t be trusted with power.

But at the same time, the Simmons Machine oversaw an era of business progressivism, as North Carolina began moving away from agriculture and toward textile, furniture, and cigarette factories that would make the state the most industrialized in the South. There was a major push for the improvement of the public schools, the creation of one of the nation’s largest road-building programs, and the rise of the University of North Carolina as the premier public university in the South.

While the Democratic Party may have reached a consensus on white supremacy, there were still major debates between party conservatives and progressives on several issues: the right of women to vote, prohibition, cleaner and fairer elections, the teaching of evolution in schools, the amount of money that should be spent to educate black children, and the degree to which government policies should tilt toward big business. And there would be factional and personality disputes as well, as various Democratic leaders bristled at the idea of taking orders from the tough party boss.

Senator Furnifold Simmons (Courtesy of the North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill)

Simmons was a product of the landed gentry of eastern North Carolina, the second of five children who grew up on a Jones County plantation near the coastal town of New Bern. The plantation had been in the family for generations and covered more than 1,000 acres and worked more than 100 slaves. Educated at what later would become Duke University, Simmons returned home to his father’s plantation, married, and two years later moved to New Bern to begin practicing law and dabbling in politics.

The political disadvantages of being a white Democrat in the state’s Black Belt soon were driven home to Simmons. The young lawyer was twice defeated in legislative races, losing to black candidates. On his third try for political office, Simmons was elected to Congress in 1886 at age thirty-four—thirteen years after his first political race. Simmons won the election when African American voters split between two black candidates—a development that was likely helped along by his politically influential father-in-law, who is said to have helped finance both black candidates.2

Although he later became the architect of the white supremacy campaigns, Simmons courted black voters as ardently as any white Democrat in the late twentieth century. For two years, he represented in Congress the district known as the Black Second. He obtained money for a post office in a black community, made sure blacks were hired for federal public works projects, and introduced a bill to establish a commission “to inquire into the progress of the colored race.” But Simmons’s experiment with biracial politics failed him in 1888, when he was unseated by a black Republican school principal. The loss humiliated Simmons, who forty years later in a radio address boasted that even though he once had lost to a black man, he “had fixed it so that forever hereafter no Negro could beat any white man for an office in North Carolina.”3

Simmons rose in politics as a talented and ruthless organizer and tactician. As state Democratic Party chairman, he oversaw a party sweep in the 1892 elections and as a reward accepted a federal patronage appointment as internal revenue collector for eastern North Carolina. His success prompted the Democrats to call on him again to run the white supremacy campaigns of 1898 and 1900. Simmons always regarded the removal of black voters as his greatest accomplishment. When his father was murdered by a black trespasser in 1903, Simmons would hint darkly that his father was “assassinated by a Negro who was perhaps seeking vengeance for what I had done.”

It was clear the spoils of the white supremacy campaigns would go to Simmons and Aycock, the strategist and the public face of the Democratic revolution. But the two men had different ideas about their political futures. Aycock wanted to be a senator, and he argued that Simmons’s administrative skills better suited him for governor. But Simmons insisted that the Senate seat was his and that Aycock be governor. The move enabled Simmons to hold power for thirty years as the Democratic Party boss.

Simmons was a short man with a long mustache who often wore rumpled clothes. Only his cold, hard, slanting eyes set him apart. He was an adequate public speaker but not a gifted one in an age of oratory. He usually let his supporters make the speeches, while he operated behind the scenes. “He was such a little man to have so much power—quiet, shrewd, and with a sense of humor which sometimes popped out like a pixie’s over his cigar,” wrote Raleigh newspaperman Jonathan Daniels. “If I ever saw a realist he seemed like one. What he had was the combination of crude and shrewd political power.” Daniels said Simmons had as much power as any Tammany Hall boss in New York City.4

He was the political boss in an age of mostly uneducated voters who often lived in relative isolation, whether in the farm country of the east, the mill villages of the Piedmont, or the hollows of the Mountains. North Carolina was last in the United States in the number of library books and had one of the lowest newspaper readerships in the country. It was a narrow world before the Internet or TV, and only toward the end of Simmons’s reign would radio and automobiles become widely available.5

Travel by candidates over poor, muddy roads was difficult, so most people never met those they were voting for. But when they did meet the candidates, it was often a memorable experience. “Election campaigns were red hot and brought to the rural districts a flavor and excitement that were relished and savored for months thereafter,” wrote journalist Burke Davis. “The staple doctrines consisted of ‘keeping the nigger in his place,’ guarding the hearthstone from priests and the Pope, drinking bootleg and voting dry, railing at Wall Street, and tipping one’s hat to the Methodist panjandrums.”6

Newspapers often were mere partisan megaphones rather than independent sources of reliable information. So networks of political supporters—county courthouse rings, local businessmen, county and precinct chairmen—had considerable influence in both persuading voters and getting them to the polls.

In an age before civil-service regulations, Simmons relied heavily on the U.S. Postal Service for political patronage. Under a Democratic president, he appointed many of the estimated 3,000 postmasters, railway postal clerks, postal inspectors, and rural letter carriers and helped decide postal delivery routes. Postal employees were often a source of political views in their communities, and many could be counted upon to help their patron at election time. As the Democratic political boss, Simmons also influenced the hiring of other federal workers, such as census takers, marshals and deputy marshals, tax collectors and deputy tax collectors, and, in the customs houses, collectors, storekeepers, and gaugers. In Raleigh there was also plenty of political patronage: state printers, fertilizer inspectors, magistrates, and other jobs in prisons, asylums, and elsewhere. Simmons also paid close attention to constituent services, helping provide flowering shrubs from the botanical gardens, ordering the government to help stock fish ponds, providing baseball tickets, and distributing free garden seeds.

But at the heart of the Democratic Party’s power was its role as protector of the white power in the South. And at the top of the machine was Simmons, the man they called the “great chieftain of white supremacy.” “The Simmons Machine reached to the headwaters of every Little Buffalo and Sandy Run in North Carolina; into every alley of every factory town,” wrote Cash. “It carefully planted as axiomatic in the people’s mind the belief that its overthrow meant inevitable subjection to their ex lackeys. He was the symbol of white supremacy. Topple him, it toppled.”7

Jim Crow

In few other eras in American history has there been a more vivid demonstration of the importance of political power than in the South in the twentieth century. The literacy test radically changed the political equation in North Carolina. In 1896 there were 126,000 black North Carolinians registered to vote. By 1902 there were 6,100. The Republican vote was decimated all across the eastern counties. In 1896, 58 percent of the New Hanover County voters cast their ballots for the Republican candidate for governor. By 1904 the GOP vote was 4.2 percent. In Warren County, the Republican vote went from 64 percent to 10 percent. Democracy was in retreat. Fewer people were now voting. In 1896, 330,997 North Carolinians cast their ballot for governor. By 1904 only 208,615 people did so.8

If African Americans had been able to vote, white politicians would have ignored them at their own peril. But stripped of their vote, blacks helplessly watched as Democratic white-controlled legislatures and local governments passed a series of Jim Crow laws creating a cradle-to-grave system of segregation. The laws started with separate railroad cars, but it soon spread to separate hospitals, parks, water fountains, restaurant entrances, seating sections in buses, and movie theaters. Even cemeteries were segregated. Law forbade white children, who had been nursed by black women, to use school textbooks used by black children.

In 1915 the state Senate narrowly defeated a constitutional amendment to implement a plan, proposed by Clarence Poe, the editor of the Raleigh-based Progressive Farmer magazine, to create separate agriculture districts for blacks and whites. The idea was modeled after the black townships of South Africa. North Carolina’s most famous author of that period was Thomas Dixon of Shelby, whose best-known novel, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, was published in 1905 and became a best seller. A decade later the book, which glamorized the Klan, was made into the movie The Birth of a Nation, which helped make Hollywood the nation’s film capital.

Jobs once open to black men, such as barbers and carpenters, dried up. In Greensboro in 1870, 30 percent of blacks were employed in skilled occupations. By 1910 only 8 percent were. In 1884, 16 percent of the city’s black labor force worked in factories. Not a single black was listed as a factory worker in 1910.9

World War I saw thousands of black North Carolinians serve in the armed services, while others headed north to work in war-related industries. But instead of their situation improving, there was a violent white backlash across the country, with race riots in Chicago and other cities, a rise in lynchings, and a revival of the Ku Klux Klan. Governor Thomas Bick-ett, regarded as a moderate on race relations in his day, told the General Assembly in 1920 that if any of the 25,000 black North Carolinians who had migrated north wanted to return to the state, they would be welcome. “But if, during their residence in Chicago, any of these Negroes have become tainted or intoxicated with dreams of social equality or of political dominion, it would be well for them to remain where they are, for in the South such things are forever impossible.”10

North Carolina’s brand of racial segregation was a milder version than was found elsewhere in the South. North Carolina was an Upper South state, where racial fears were not as strong as in the Deep South. There was more of a sense of civility in the state—fewer lynchings, less racist rhetoric from politicians. There were five state-supported colleges for blacks—the most in the South. Prodded by the threat of federal lawsuits, North Carolina was among the first southern states to create graduate programs at black colleges and to begin closing the huge gap between the pay of white and black public schoolteachers. Outside observers saw in North Carolina a forward-looking state that was more open to the aspirations of its black citizens.

But black North Carolinians often saw something else. And if black North Carolinians could not use the ballot, they could—and did—vote with their feet.

Black people started moving north after emancipation. But the stream of black people became a river following World War I. By train, automobiles, and buses they headed to New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Washington, D.C., and West Virginia. Between 1910 and 1930, an estimated 57,000 black North Carolinians headed north. The migration slowed during the Depression of the 1930s and then accelerated during the 1940s, as blacks sought work in northern defense-related industries during World War II. Between 1930 and 1950, an estimated 222,000 black North Carolinians packed their bags.11 The great migration profoundly reshaped North Carolina’s demographics. In 1880 black people composed 38 percent of North Carolina’s population. By 1950 it was down to 27 percent, and by 2000 it was 22 percent.12

Progressivism—For Whites Only

As Simmons headed to Washington, North Carolina was in the early stages of the Progressive Era—part of a national reaction to the Gilded Age of robber barons, powerful railroads, and big-business monopolies. On the national scene, the era produced populists such as William Jennings Bryan and progressives such as Republican Teddy Roosevelt and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. This was the era of corporate trust-busting, muckraking, and governmental reform. In the cotton fields and small towns of the South, there was still a deep suspicion of Wall Street.

The Democratic Party was now the undisputed master of North Carolina politics. But it w...