![]()

PART I

Christian Diversity in America

The amazing diversity of Christianities in the United States has numerous sources. Many traditions arrived in the cultural luggage of immigrants, from Europe or Asia, from Ethiopia, or from the Caribbean. Other groups, including the Assemblies of God and the Latter-day Saints (Mormons), arose as new Christian movements in the United States. Still others emerged in the aftermath of controversies over doctrines, ethnic differences, or regional tensions such as those that fractured Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians in the years preceding the Civil War. On some occasions, church unions have temporarily reduced the number of different Christian denominations, only to see them expand again when clusters of congregations refused to go along with the merger. Nor has Christian diversity followed neatly along denominational lines. A Presbyterian in the eighteenth century might likely have embarked from Edinburgh, but today a Presbyterian immigrant is more likely to have arrived from Seoul. As this implies, since late antiquity Christianity has been peripatetic, with borders that are porous and potentially creative when it encounters other traditions, including both other forms of Christianity and other religions. Hence, as Michael McNally demonstrates with respect to Native American Christianities, along with the tragic violence of colonialism, cultural assimilation, and missionary encounter, “it is also important to register just what Native peoples, with considerable resolve and resourcefulness, have made of the missionaries’ message.” This opening section of American Christianities, beginning with an overview from historian Catherine Albanese, provides readers with a historically informed perspective on the sources and extent of this variety.

These various Christian groups continuously face decisions about how they will relate to one another, to non-Christian religions, and to the wider society. Through these decisions, Christians and other religious communities situate themselves in what Jonathan Sarna calls “the marketplace of

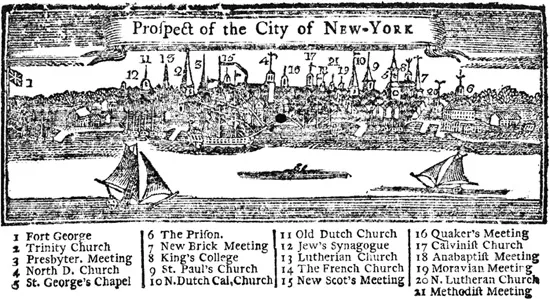

FIGURE 1. Prospect of the City of New York, 1771. This woodblock reveals both the remarkable number of Christian churches in eighteenth-century New York and the way that Christian symbols once dominated the city’s skyline. Collection of the New-York Historical Society, Negative #72730.

American religion,” a civic setting in which many forms of cooperation and coexistence are possible but which can be threatened when any specific group attempts to enlist governmental support for its version of religion. This section therefore illustrates and analyzes the historical processes by which specific Christian groups have resisted, adapted, and borrowed from their religious and social environment in order to develop a distinctive understanding and practice of Christianity. These distinctive practices fashion communal identity at many levels. They may meld Christian rituals and symbols with specific ethnic or racial traditions. They may counterbalance the hostile or exclusionary practices of more powerful groups. They may accentuate a group’s separate or elect status, but they may also celebrate religious experiences or ethical commitments that transcend institutional and ethnic boundaries. As James Bennett points out in the concluding chapter of this section, “relations among American Christians have moved along a continuum ranging from intense and even violent conflict at one end to remarkable cooperation at the other.” Given these variables, part 1 of American Christianities includes chapters that approach Christian and other diversities from a general and comparative perspective as well as chapters that offer illustrative case studies of Native American, Asian, Latino, and African American Christianities.

Finally, within the religious marketplace, where adaptation, reinvention, and borrowing are constant features of active religious life, Christians—whether self-consciously or not—make decisions not only about relationships to other religious and social groups but also about the relationship to their own religious past. Tradition undergoes constant changes of emphasis, style, and interpretation. As many chapters in this section illustrate, “Christian Diversity in America” includes variation and change over time as well as diversity across geographic space and social location. Indeed, Christian groups frequently find variation over time more troubling than the diversity among their Christian neighbors, since the continuance of cherished rituals from generation to generation and the stable transmission of authoritative texts, beliefs, and institutions are close to the core of religious society. As with all of the four parts of American Christianities, the intent is not to “cover”—even if that were possible—every form of Christian diversity but rather to select and interpret especially important illustrations of the social and historical processes that have generated that diversity.

![]()

Understanding Christian Diversity in America

CATHERINE L. ALBANESE

Christianity shapes people to think in terms of oneness. Ideologically, there is one God over all nations, and there is one Great Commission from Christ to the nations. Historically, there has been one “true church”—whether conceived in material form as in medieval Europe or understood spiritually as in post-Reformation theologies. Historiographically, generations of American religious historians (originally, church historians) played off all of this as they wrote this nation’s religious history. Their story line proclaimed Protestant consensus and, with the passage of time, increasing departures from it (unhappily, in the view of the earliest consensus historians). Moreover, the departures kept impinging in increasingly noticeable ways. By 1972 and the last great monument of the consensus school—Sydney Ahlstrom’s A Religious History of the American People—the story and its ideological center were growing more suspect. For its part, the Ahlstrom work ended in lament for a Puritan center that was no longer holding and organizational puzzlement over how to chart events and movements still unfolding. The next decades brought consensus historiography down—first in an avalanche of postmodern protest against grand narratives and then in plural and postplural paradigms that alternately emphasized conflict, toleration, or religious blending.1

To a great extent, however, the emerging story line(s) stressed two points. The first—found in older work in the field—contrasted a Christian center with a “sectarian” Christian periphery and then moved past it to discover even greater Christian diversity. As early as 1937, for example, Elmer T. Clark’s Small Sects in America was making the point about difference. And as late as a year after the publication of Sydney Ahlstrom’s work, Edwin Gaustad’s Dissent in American Religion (1973) appeared and became a small classic.2 But by that time, historians (including Ahlstrom) had already modified the narrative as they moved toward greater notice of diversity, and the church-sect model increasingly broke down. Historians were pointing to the large presence of a Catholic population, to immigrant and black Christian expression, to the post–Civil War bifurcation of Protestants into liberal and conservative camps, and to a series of other topics that suggested Christian variety.3 Thus, by the 1980s, difference was beginning to be construed as normal, not exceptional. Consider, for instance, Richard Pointer’s Protestant Pluralism and the New York Experience, produced at a time (1988) when pluralism had become a feature of American religiosity to be admired and celebrated.4 In keeping with the new paradigm, Pointer found colonial New Yorkers not only tolerating one another’s religious differences (mostly Protestant) but even modifying their views to accept the situation as positive and beneficial.

The second point of the story line, however, went further than noticing major features of American Christian diversity. A new historiographical consciousness about American religion grew out of the encounter of the old Christian center with non-Christian people and commitments. Moving past domestic Christian pluralism, what now came through as strikingly different for American religious historians was all those non-Christian others—Asians and the Fiji Islanders, Lebanese and Syrian Muslims, denizens of new non-Christian American religious movements, Native American traditionalists, Hindus and Buddhists and Sikhs. But what of intra-Christian pluralism? Had historians delved deeply enough and come sufficiently to terms with the multiplied forms in which American Christianity had thrived and proliferated? Had they encountered the full landscape of diversity or only its largest, most undeniable landmarks and formations? Arguably, despite the nods to pluralism within Christian ranks, it is worth asking whether the diversity within American Christianity itself had been less than fully examined as it evolved in new locations and situations. And it is worth asking what happens to the narrative of American religious history if the question is answered affirmatively.

Hence, in what follows, I offer evidence—as do the other essays in this volume—for an underexamined story of Christian diversity in America. It is a story more complex than the tale of curious “sects” and “also-rans,” or of noticeably unusual variations, or of a few large bodies or social situations that stand out from the crowd. As I hope this essay demonstrates, it is time to pay more attention to a body of historiographical material that has not been sufficiently examined or seen in relationship to other accounts. Looking at this story in this way, in fact, has precedents, especially in the work of recent interpreters of “global Christianity.”5 Here in the United States, however, at least three historiographical myths (in the colloquial sense) about the unity of American Christianity and its decline have percolated through standard assessments. Myth One asserts that the Christian story, especially before the Civil War, is mostly about Europeans. Myth Two declares that the Protestant Christianity of European settlers was, at its beginnings, virtually monolithic. Finally, Myth Three views Christian pluralism as a late-breaking development, a post–Civil War and especially twentieth-century and later phenomenon.

Describing Difference

The Horizontal Axis

If we conceptualize differently, however, we can look at the more-nuanced account that these myths obscure and also attend to a story of variety and difference that developed in a series of ways. In brief, if we examine American Christian diversity as a reality with both horizontal and vertical vectors, we can glimpse the outlines of a rich and productive narrative. We can render a fuller account of how modern Christianity in America became so diverse.

What are these “horizontal” and “vertical” vectors? One way to think about the horizontal in Christianity is to see it as a spatial or typological or denominational set of proclivities. Where, geographically, can we locate different kinds of Christianity in America? In comparative terms, can we identify types or variants that are meaningful? In organizational terms, what are the institutions that embody these different forms? In other words, leaving aside changes that came with time, what have been the regional, ideological, and structural religious possibilities for Christian expression? On the other hand, thinking in terms of the vertical dimension, how can we factor in the developments as the American Christian story—or, better, stories—unfolded through time? Old-country forms of Christianity came with cultural baggage attached but encountered strangers’ forms of Christianity and bounced off them. So old forms changed, even as they sparked newer, separate versions of Christianity in a plethora of new denominations, sects, and movements. How do we tell the story/stories, when most religious things, it seemed, were up for grabs and modifications?6

Turning to the horizontal axis first, regional forms of Christianity flourished from the time of the first settlers, and later developments served to encourage regional enclaves. Even a cursory glance at early American Christian history highlights the presence of separate groups of Christian believers in different sites. British presence dominated in New England and Virginia, but in New York it was tempered by the Dutch Reformed presence that came with the colony’s initial days as New Amsterdam. In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Scandinavian Protestants—Lutheran and sometimes sectarian—had preceded the inauguration of the Quaker colony. A strong German Lutheran and sectarian cohort could be witnessed especially in eastern Pennsylvania and in its burgeoning new city of Philadelphia. Maryland was established initially by the Catholic Lords Baltimore and was only subsequently upstaged by Protestant rule.

Meanwhile, outside the British North Atlantic colonies, in what is now the state of Florida, French and Spanish forces vied for control until the Spanish founded the city of St. Augustine in 1565. Catholic Christian presence had been established. By the end of the sixteenth century, the Spanish had also taken control of New Mexico, and the Franciscan friars began their ministry there. The Jesuits appeared in the present state of Arizona by 1700. In eighteenth-century California, the fabled mission system, organized by Franciscan Father Junipero Serra, included, at its height, some twenty-one stations designed to be model Indian settlements. A century and more earlier, French Jesuits had already fanned out across the upper Midwest to convert Huron peoples and had ventured further east to missionize the Iro...