eBook - ePub

Made In Egypt

Gendered Identity and Aspiration on the Globalised Shop Floor

This is a test

- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This ground-breaking ethnography of an export-orientated garment assembly factory in Egypt examines the dynamic relationships between its managers – emergent Mubarak-bizniz (business) elites who are caught in an intensely competitive globalized supply chain – and the local daily-life realities of their young, educated, and mixed-gender labour force. Constructions of power and resistance, as well as individual aspirations and identities, are explored through articulations of class, gender and religion in both management discourses and shop floor practices. Leila Chakravarti's compelling study also moves beyond the confines of the factory, examining the interplay with the wider world around it.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Made In Egypt by Leila Zaki Chakravarti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE FACTORY AS CRUCIBLE

‘So this is phase two of the revolution … what we need to do now is to take Tahrir to the factories.’

In May 2011, some three months after huge crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square had jubilantly celebrated the forced removal of Egypt’s long-serving President Hosni Mubarak, the Guardian newspaper’s online series ‘The new Egypt: 100 days on’ carried a guest column by Hossam al-Hamalawy.1 al-Hamalawy had long been a prolific blogger and tweeter on Egypt’s Arab Spring upheavals, using a wide gamut of social media.2 Writing in English as well as in Arabic, he was amongst the most prominent of Egypt’s representatives of what Thomas Friedman later came to call the ‘Square People’,3 characterised as ‘mostly young, aspiring to a higher standard of living and more liberty, seeking either reform or revolution (depending on their existing government), connected to one another either by massing in squares or through virtual squares or both’.

Taken at face value, al-Hamalawy’s ‘To the factories!’ exhortations might easily be dismissed as the trendy musings of a Westernised urban intellectual, disconnected from the realities of everyday life outside Egypt’s e-savvy enclaves of privilege. In fact, though, he had been one of the first to draw explicit attention to the ‘crucial but under-researched’ (Gunning and Baron 2013: 59) role which widespread labour unrest played in the build-up to Mubarak’s downfall. Blogging in its immediate aftermath on his ‘3arabawy’ website, he wrote:

In Tahrir Square you found sons and daughters of the Egyptian elite … But remember that it’s only when the mass strikes started three days ago that’s when the regime started crumbling … Some have been surprised that the workers started striking. I really don’t know what to say. The workers have been staging the longest and most sustained strike wave in Egypt’s history, triggered by the Mahalla strike in December 2006. It’s not the workers’ fault that you were not paying attention to their news.4

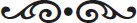

The distinguished labour historian Joel Beinin and others (Abdalla 2012; Achcar 2013; Gunning and Baron 2013; Tripp 2013; Abdelrahman 2014; Gerges 2014; Schenker 2016) have published collated data on the overall scale and nature of labour unrest in Egypt,5 showing a pattern of successive waves building to the denouement highlighted by al-Hamalawy (Figure 1.1). Beinin had also been assiduous in chronicling many of these labour disputes at the time they were unfolding (2005, 2006, 2007; Beinin and al-Hamalawy 2007a,b). His accounts of the 2006–7 Mahalla strikes vividly describe how workers had become embittered towards their managers, as, for example, when they held aloft placards saying ‘Ilhaquna! (Come to our rescue!) Il-haramiyya saraquna! (These thieves have robbed us blind!)’ (Beinin 2007).6 In other instances criticisms were more personalised, as when in 2007 striking textile workers in a factory in Kafr el Dawar publicly excoriated their Chairman with the expletive ‘Ali gazma! (Ali is a shoe i.e. worthless)’.7 And in 2005 workers at a recently privatised factory in Qalyoub openly complained to the press about their new proprietor and his allies:8

We are dealing with a regular mafia here. Do you think we’re joking? This man tried to wipe out all our rights. He really showed us the ugly face of privatisation.

Figure 1.1 Industrial labour actions in Egypt

Yet it was in the preceding year of 2004, on a hot summer afternoon in the Mediterranean city of Port Said, that I had found myself experiencing a radically different kind of labour demonstration, as the employees of the privately owned garment manufacturing company to whose shop floor I had secured participant-observer research access drove around in electorally festooned factory buses, supporting their own proprietor’s candidacy in the elections then underway for the Upper House of Egypt’s Parliament shouting slogans such as ‘Entikhbo (vote for) Qasim Fahmy! Ism Allah ‘aleh (the name of Allah be upon him)! Hami rayetna (the protector of our flag)!’ From my seat, jammed in among the giggling, cheering female workers, there was nothing forced about the demonstration. These workers were as enthusiastic in support of their proprietor as the workers of Qalyoub, Kafr el Dawar and Mahalla were in repudiation and condemnation of theirs. As I look back on my time on the shop floor from February to December 2004, inevitably now through the prism of all that has happened in Egypt since then, I am still struck by the totality of the contrast and intrigued by the underlying causes and factors which might explain it.

These go deeper than obvious factors such as the presence or absence of organised trade unions. When Nasser nationalised the most important sectors of the Egyptian economy in the state socialism of the 1950s, the only unions that were legally permitted were a limited number of national, sector-specific unions (including the General Union of Textile Workers), all of which were branches of the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (Posusney 1997; Pratt 1998). From its inception in 1957 the ETUF operated as, in effect, an arm of the security state, controlling its millions of registered workers in state-owned enterprises, and frequently marshalling them in active political support of the Nasser-Sadat-Mubarak regimes. Though strikes were, in theory, permitted, they could only legally take place with the authorisation of a two-thirds majority of ETUF’s Board (which consisted of regime appointees) – and in its entire history the ETUF only ever authorised a total of two strikes. The wildcat strikers of the state-owned enterprises and recently privatised firms who galvanised and made up the waves of labour unrest charted above were, as a result, almost invariably as vehement in their denunciations of their ETUF representatives as they were towards their management. And as Figure 1.1 shows, the fact that private sector company employees were legally forbidden (and sometimes beaten up and physically prevented) from forming independent trade unions did not in any way mean that private factories and firms were free from labour unrest. In my own fieldwork site, my time on the shop floor was marked by a seemingly endless series of management–labour arguments, fights and disputes. Yet my co-workers evidently had fostered a social contract with their proprietor that was honoured on terms different from those which the striking workers of Mahalla and other factories had with theirs.

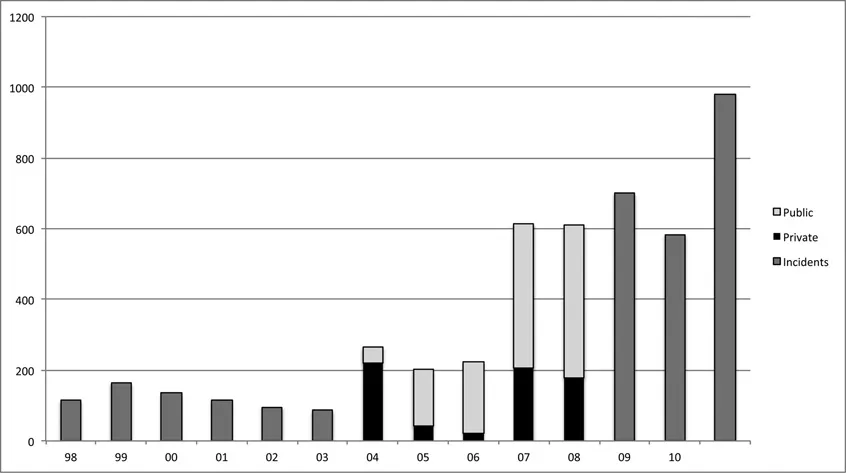

At the time of my fieldwork in 2004, Fashion Express (as I will call the firm, using a pseudonym) was an export-orientated garment manufacturing enterprise, located within Port Said’s Export Processing Zone (EPZ) at the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The EPZ was one of nine such onshore tax havens established by the Egyptian government to enable export-orientated garment and other manufacturing to boost local economies and employment opportunities. The firm was run as a family business by Qasim Fahmy, who was also its local investor, employing a workforce of 450 male and female employees. In seeking to understand the management–labour dynamics in play, I have focused my ethnographic research on ways in which categories of gender, class and religion intersect on a labour-intensive shop floor which, because of the export profile of the firm, provides a nexus where myriad global and local economic forces interact to influence the environment of the workplace.

My research also aims to break new ground in the literature of gender and work in the Middle East by providing an ethnographic account of the public and visible economic activities of women in an institutional workplace within the formal economy. For although issues relating to women and gender have received considerable attention in Middle East studies (Meriwether and Tucker 1999; Keddie 2007; Whitlock 2007), when it comes to women’s increasing economic roles it is the informal sector that most studies have emphasised. Even here, with the exception of a handful of ethnographies covering women’s economic activity in home-based work and related areas (Rugh 1985; Hoodfar 1997a; el-Kholy 2002; Rugh 1985; Sonbol 2003), most studies have taken as their focus communities where women’s educational backgrounds have not qualified them to seek work in the formal economy, causing them to rely primarily on self-help initiatives and informal networks (Early 1993a,b; Singerman and Hoodfar 1996; Bibars 2001; Barsoum 2002; Assad 2003; Ismail 2006; Assad and Barsoum 2009). This study aims to address this lacuna with an ethnography which recognises women as active economic actors within the public workplace. The research thus has dual, intertwined objectives: on the one hand, to provide an ethnography of a hitherto ‘hidden’ community, and on the other to interrogate the ethnographic data in order to explore issues of gender, class and religion in a context that has not yet been analysed.

In this introductory chapter I ‘set the scene’ for Fashion Express, the factory that was my research setting, and summarise the main points of focus, inspiration and methodological challenge for my research. In doing so, I first of all describe the distinctive urban environment of Port Said, highlighting the continuities between the present and the past which inform the city’s daily life. Next I focus on Fashion Express, describing ‘the factory as blueprint’, the type of ordered, efficient enterprise which any management would wish to present to prospective international clients within the complex subcontracting chain that characterises the globalised garment industry (Lim 1990; Cairoli 1999; Rofel 1999; Kabeer 2000; Collins 2003; Hale and Willis 2005; Hewamanne 2008). An immediate dislocation, however, becomes apparent between the ‘smoothly humming machine’ that the factory is designed to operate as, and the stop-go production cycle it is forced to operate by ‘famine and feast’ peaks and troughs in the orders actually coming in.

I then describe the workforce which populates the blueprint, deliberately adopting the technocratic, de-humanised perspective of the official ‘manpower statistics’ which I was given. From there I shift my focus to the human beings behind the raw labour statistics, who were my colleagues, my informants and my guides during my time on the shop floor. It is the lived experience of their daily lives which provides, in Lévi-Strauss’ ringing formulation, ‘a means of assigning to human facts their true dimensions’ (Lévi-Strauss 1967: 52). A sharp contrast emerges between the anonymous, dehumanised, smoothly efficient perspective of the factory as blueprint, and the chaotic, raucous social experience of the human beings who populate it.

This contrast provides the basis for identifying the research questions which guided this study, and which I set out in the following section. I move on to reflect on some of the theoretical insights and understandings from other scholars that inspired and challenged me as I fought to make sense of the welter of impressions and insights in which I was submerged, and highlight the principal methodological challenges and ethical issues that I found myself facing. Finally, I end this introductory chapter by setting out the sequence of the chapters that follow.

Port Said – the nation’s ‘Dual Frontier’

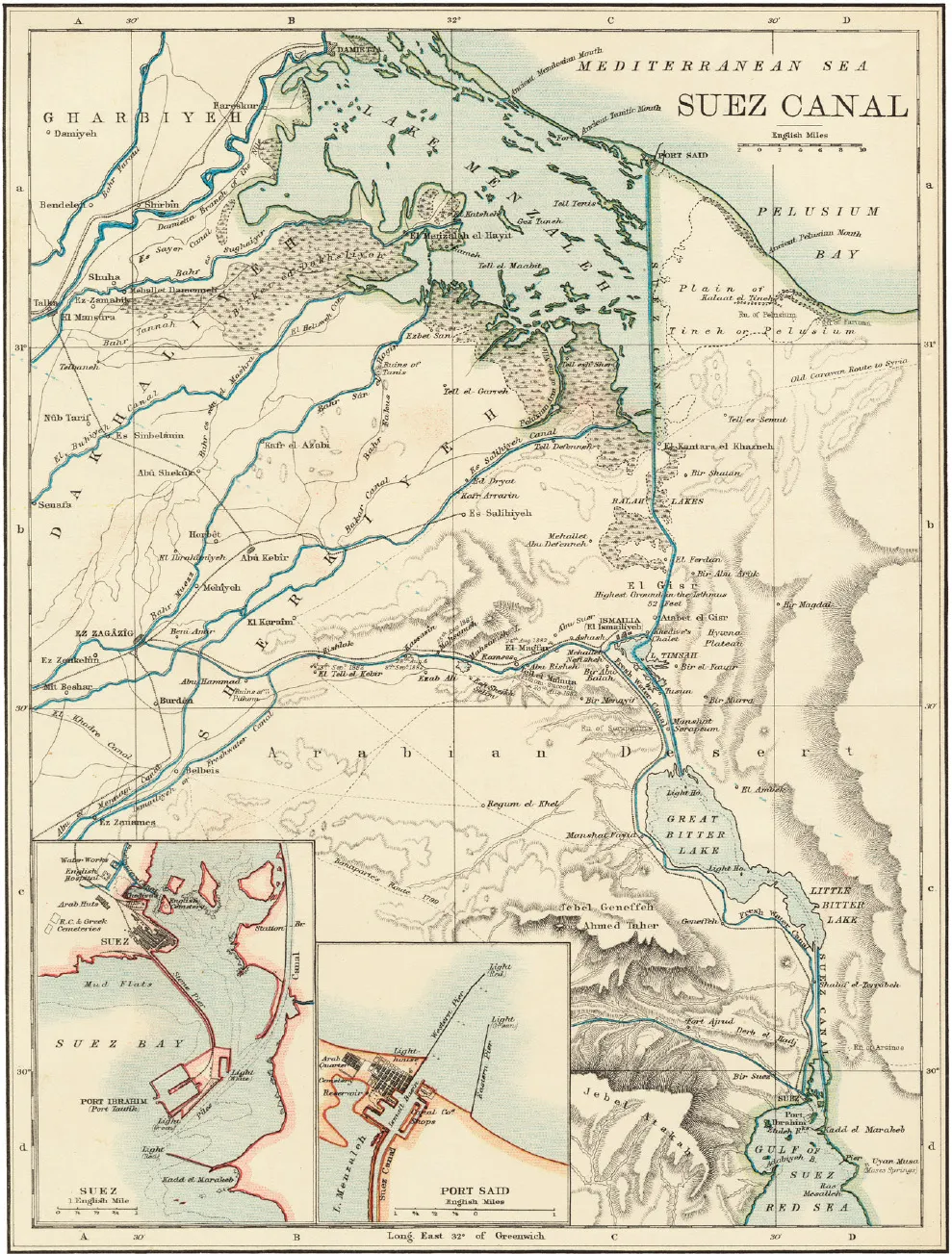

Port Said (Map 1.1) is one of Egypt’s more modern cities, built on previously empty desert in the 1860s (Modelski 2000; Karabell 2003) at the time of the construction of the new canal named after the port city of Suez, located at its opposite end (Map 1.2). Egypt is a land whose centres of human habitation typically trace their origins hundreds – sometimes thousands – of years into the historical past: Suez, for example, traces its history as a city back at least to the 8th century AD (CE). By contrast, Port Said has always been one of Egypt’s most enduring icons of modernisation, industrialisation and internationalisation – the nation’s ‘Dual Frontier’, both spatially to the outside world and temporally to a modern, globally engaged and prosperous future.

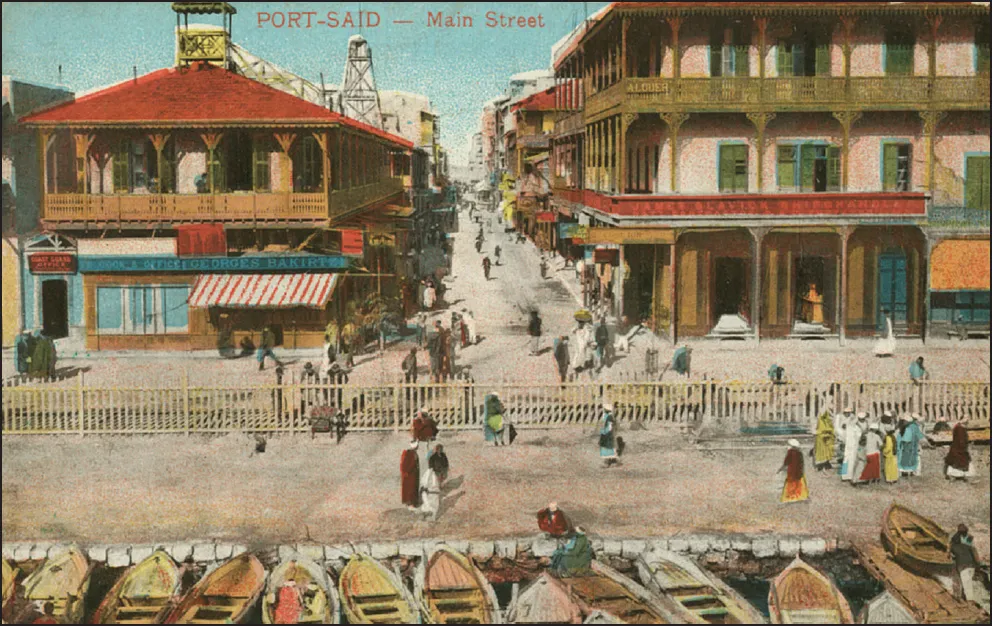

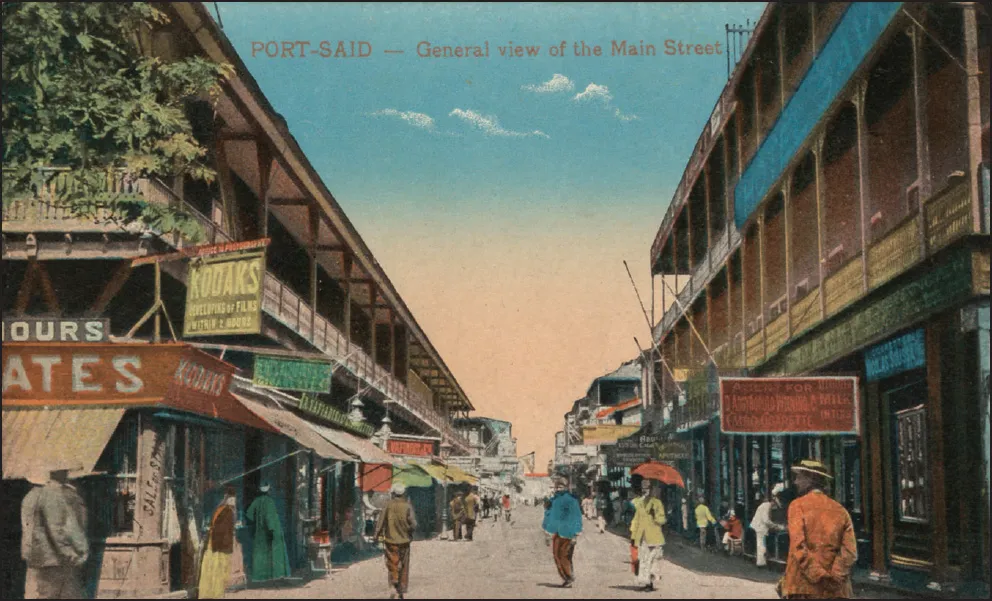

From the city’s foundation through to the overthrow of the monarchy by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Free Officers Revolution of 1952, Port Said maintained a reputation (global as well as domestic) for its commercial elan and European elegance – along with a parallel notoriety for its somewhat raffish docklands lifestyle. Urban planning and development was deliberately modern, on a rigorously rectangular grid of roads and boulevards. Along the northern corner of the west bank of the Canal stretched the Quartier des Affaires (what we would now call the Central Business District), with its bustling shops, offices, diplomatic representations, cafes, restaurants and hotels (see Illustration 1.1). These shared an architectural template distinctive to the city, and in particular very different from the multi-storey Parisian-style buildings of belle époque Cairo (Myntti 2015). The Port Said style was low-rise, and marked by the elegant wooden, often intricately carved, balconies and frontages to be seen adorning the different buildings (Illustration 1.2).

Map 1.1 Port Said and the Suez Canal

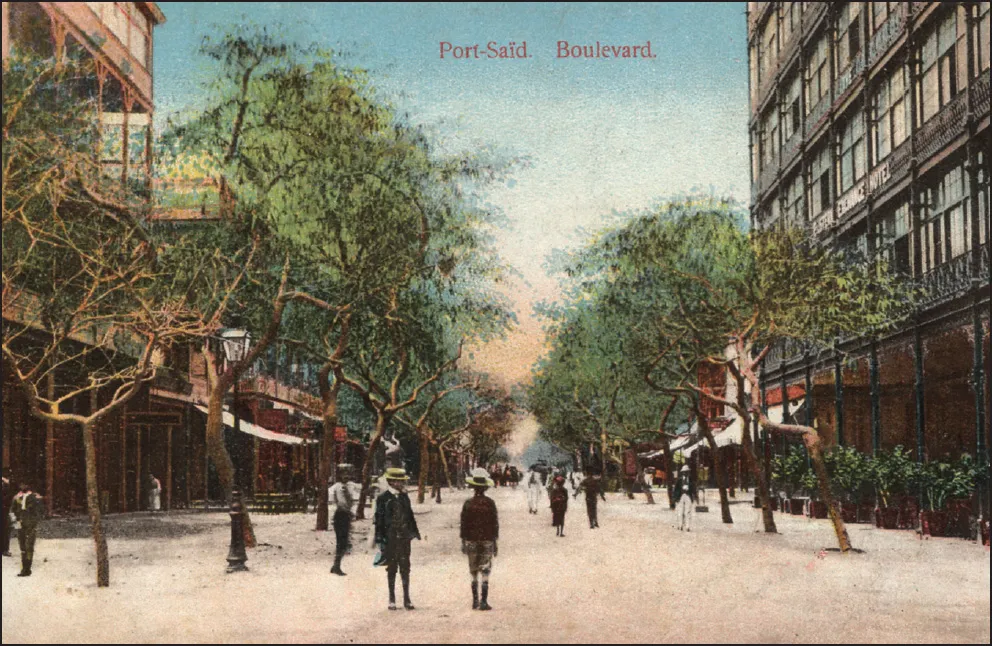

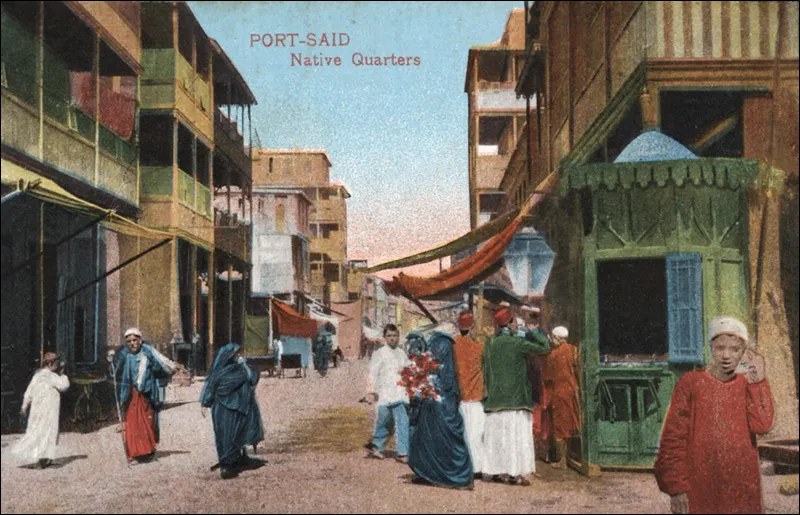

A few blocks inland was the Quartier Residentielle, its elegant villas and apartment blocks maintaining the Port Said aesthetic along tree-lined boulevards and garden squares (Illustration 1.3). Further west was the designated ‘Village Arabe’, which, though visibly less affluent than the modern European city, nevertheless maintained organisational and aesthetic continuity with it (Illustration 1.4).

Even during the austere years of Nasserist state socialism, the passage of foreign ships, goods and people through the newly nationalised canal (underpinned by the continuing vigour of local traditions of smuggling, contraband commercialism and other forms of shady or illegal business activity) enabled Port Said to sustain its reputation as Egypt’s point of engagement with the excitement, glamour, temptation and consumer choice with which the outside world continued to beguile the nascent Republic. The abortive 1956 British-French invasion brought into focus the port-city’s strategic military significance, adding to its self-consciously modernist self-image a strong sense of pride in its reputation for fiercely defending the motherland against British, French and later Israeli forces (Farnie 1969; Hamrush 1970; Najm 1987; Hewedy 1989; Kyle 1991; El-Kilsh 1997; Turner 2006).

Map 1.2 Antique map of the Suez Canal (1897)

Illustration 1.1 Early Port Said – Quartier des Affaires (1910s Postcard)

Illustration 1.2 Early Port Said – Rue du Commerce

Illustration 1.3 Early Port Said – Quartier Residentielle

Illustration 1.4 Early Port Said – Quartier Arabe

Following Egypt’s defeat in the 1967 Six Day War, the bustling port fell on hard times. The opposing armies facing each other across the Canal converted it into what Moshe Dayan is reputed to have called ‘one of the best anti-tank ditches in the world’, with the Egyptians blockading all traffic, and the Israelis building a twenty metre high fortified wall of sand along the length of its Eastern bank. At the same time the Egyptian government forcibly evacuated all civilian residents from the city, dispersing them across urban and rural centres throughout the country in what locals still refer to as their years of hijra (deliberately borrowing the term in Islamic history for the Prophet Mohamed’s temporary retreat from Mecca to regroup in the city of Medina).

In 1975, riding high on Egypt’s military breakthrough in the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the cessation of hostilities with Israel, the newly consecrated Batal il-Ubur (Hero of the Crossing i.e. of the Canal, by Egyptian forces) President Anwar Sadat led the reversal of decades of Nasserite state-socialism by declaring his new economic infitah (opening) policy to reinvigorate and develop international trade and commerce, and so end decades of socialist austerity, war and economic difficulties. A key measure was the re-...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations, Maps and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Transliteration

- Map of the Nile Delta

- Chapter 1 The factory as crucible

- Chapter 2 Firm as family – control and resistance

- Chapter 3 Shop floor as marketplace – love and consumption

- Chapter 4 Daughters of the factory – discipline and nurture

- Chapter 5 Globalised takeover – performance and resistance

- Chapter 6 Domination and resistance

- Appendix The Fashion Express workforce

- Select Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index