![]()

PART I

THE CHIASM OF RHETORIC AND CULTURE

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE RHETORIC CULTURE PROJECT

Stephen Tyler and Ivo Strecker

THE RHETORIC CULTURE1 project arises from a fundamental chiasmus that leads us to explore the ways in which rhetoric structures culture and culture structures rhetoric. It calls for a program of research whose basic topics are the interrelationships between cultural forms of practice, passion, and reason; and it seeks to understand the culturally generated orders of discourse—and their technologies of production.

In a world whose imaginative processes and social structures are seemingly undergoing dramatic reconfiguration brought about by the technology of the Internet and other media, it may seem anachronistic to look for inspiration in rhetoric, which many would not hesitate to call antiquated, even discredited. These new technologies of communication have, however, merely brought problems of social order into sharper focus, without being able to provide solutions to the problems they entail. It is for this reason that we turn to rhetoric, for rhetoric holds out the possibility of a contemporary discussion that is not at the outset informed and predetermined by the structure of technology.

This is no mere nostalgia, and we conjure no elegies for lost utopias. Rather, we argue that rhetoric, long abused in the modern era, has emerged in postmodern times as an organizing concept for an all-embracing study of discourse and culture. Its emergence is coupled with a crisis in representation brought on by the failure of the foundational metaphor of “language-as-the-mirror-of-the-real” (Rorty 1979). The concept of representation, of the substitution of signs for originary objects, enabled a consensual community sustained by an order of discourse founded in reason, truth, logic, and plain style, and was based in the separation of fact and value and in the idea of language as a transparent medium having a shared code and an analytically determined essence.

Modernity evolved under the aegis of a technology of representation using moveable type, the idea of the book, and of writing as the dominant instrument of reason. That technology is passing, being replaced by other forms of imaging and storing information (Ong 1982). This “new imaginary” accomplishes a redirection of human action and intention that is essentially a return to the rhetorical ideas of inventio and memoria, and despite its electronic gadgetry, aligns itself more closely to the means of oral discourse than with those of writing-in-the-sense-of-the-book.

Rhetoric is often understood as a mere instrumentality, a means of persuasion, but it is as frequently treated as an object of discourse. These uses of rhetoric are not independent and may be deployed alternatively or even simultaneously. The interplay between these modes of instrument and object also characterizes the discourse about culture. Culture, or cultures, can be discursive objects at the same time as they are self-revealing instrumentalities of a discourse. Objects and instruments of discourse are thus co-constitutive, autopoetic processes in which objects become the objects they are by means of their instrumentalities, and their instrumentalities become the instrumentalities they are by means of their objects. This same process characterizes the relationship between rhetoric and culture. While rhetoric can be the instrument with which we describe and understand culture as the object, culture is also the instrument through which we understand and locate rhetoric.

Inasmuch as we think of rhetoric taking itself as its own reflexive object, we are tempted to think of this moment in which rhetoric is displaced into its own instrumentality as some kind of higher order meta-discourse that we might call the theory of rhetoric, but that is not the case. The interaction and interpenetration here has no dialectical consequence in which object and instrument are overcome or subsumed under some more inclusive neutralization or transcendence of their supposed opposition. There is instead a kind of alternation between object and instrument that may produce change but no necessary development. The same kind of relation obtains in the case of culture taking itself as its own object.

This underlying reciprocity enables different moments in the interaction of culture and rhetoric. One possibility, and perhaps the easiest to conjure, is the ethnographic account of rhetorical practices in different cultures, what we might call the single-voiced rhetoric of a culture in which rhetoric is a cultural object, as it might be in something like “The Rhetoric of Koya Marriage Negotiation.” In a more complex form, we have critical accounts of those rhetorical practices that enable the production of cultural descriptions and comparisons. Here the focus shifts to something like “the rhetoric of the description.” While we might call the first mode “rhetoric in culture” and the second “rhetoric of culture,” it should be understood that both modes are usually carried out simultaneously. The critical moment might be something as simple as appendages to a description in the form of asides, footnotes, skeptical queries, framing stories, or the poetry of methodology. Here the monological voice of the observer becomes a skeptical dialogical voice conducting a kind of internal argument with itself or imagined others. In more interesting reflexive ethnographies, such as Gregory Bateson’s Naven (1936), these modes of critical commentary are more complex. They consist of deconstructive, internal reflections on intention, inference, evidence, and representation in which Iatmul culture is produced simultaneously with its dissolution. In either case, these marginalia, whether they are in the form of internal commentary or of external intertextual critique, destabilize both the initial account and themselves.

The Rhetoric Culture project explores the possibilities afforded by rhetoric to explain culture. It does this by paying more attention to the hidden in social discourse, the unsaid behind the said, the latent beneath the manifest, and the unreasonable as well as the reasonable sides of human existence. It emphasizes multivocality as much as univocality, understanding as much as translation, imagination as much as decodation, and it adds, or rather brings back, the ideas of emergence, creativity, construction, and negotiation to the ideas of episteme, knowledge, representation, rules, and symbol/sign systems. But it does this without necessary reference to the notion of meaning, for understanding is not exclusively or even primarily dependent on meaning, or knowing the meaning, or symbol interpretation, but comes about as much through sensibility, which includes sense making, feelings and empathy.

Here the ideas of story and exempla are of key concern, for when we understand something, it is more often than not because it is embedded in a story or examples, where particulars portend the whole. Rhetoric Culture studies acknowledge this central role of narrative and the unfolding character of understanding, and seek to give an account of the imaginative resources that ground our approximations and yield our openings and closings.

The concept of rhetoric culture does not accord with those oppositions between literate and nonliterate, civilized and savage, fact and fiction, origin and telos, culture and nature, signifier and signified, spirit and material, mind and body, reason and passion, figurative and literal, apparent and real, or past and present that made the structure of modern dialectic and constituted themselves in easy antithesis. Similarly, it does not privilege speech over writing and is responsive to all technologies of discourse. It does not give priority to either the speaker (the oratorical mode) or the hearer (the hermeneutic), or to the code (structuralism). Classical rhetoric privileged the idea of the speaker and the speech event. Later rhetoric privileged the author of the text. No one (except in later hermeneutics) consistently adopted the perspective of the hearer. Critique focused chiefly on the text as a structural object or a code of symbols. We do not want to abandon these loci, but argue that no one of them alone dominates as the origin or starting point of understanding. Partly as a consequence of not privileging the code, the idea of Rhetoric Culture does not privilege truth over opinion or persuasion. These, and others, are merely kinds of things we try to do in communication. Consequently, it is better to abandon the idea of independent genres correlated with the different modes of rhetoric (logos, ethos, pathos).

We may give the appearance of separately engaging one or another of these modes for “rhetorical” purposes. Common practices in scientific writing, for example, are entrained in order to give the appearance of a discourse structured and motivated solely by logos. Similarly, we may wish to convey moral certitudes without appeals to reason as if these certitudes were reason unto themselves, or at least beyond reason. In our everyday discourse as well, we trim these different rhetorical modes to the measure of our needs and desires, exploiting their possibilities either separately or jointly as we judge their relative efficacy in the emergent situation they create—as in the strategies of politeness analyzed by Penelope Brown and Stephen Levinson (1978).

Even so, we are not in complete control of our instruments. Much as we may try to exploit these different modes, either by separating them or by compounding them into judicious mixtures, we cannot really employ one of them in complete isolation from the others any more than we can fully control or predict the synergies of their combinations. At best, we manage to convey the appearance of control, which fortunately is sufficient to the moment, or at least as it is judged by its contemporary effects. All fixed genres are mixed to various degrees and in various ways, and all exceed our attempts to keep them under our thumbs. Even if we could achieve total authorial control, our audiences and interpreters might nullify or reconfigure our intended effects, for there is no way effectively to control the interpretive responses of our interlocutors.

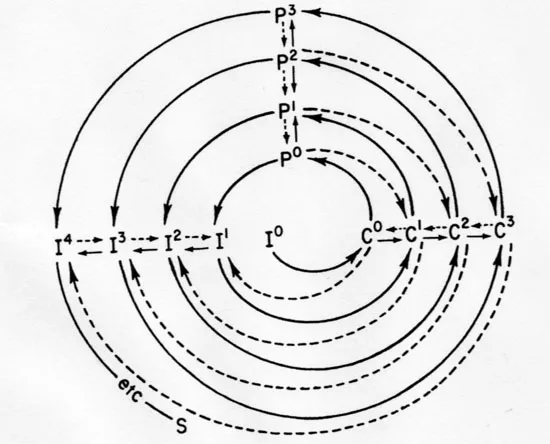

The following model illustrates this open-ended and emergent nature of discourse. It shows how in prospective and retrospective fashion, speakers’ intentions (I), their competence (C) or awareness of existing conventions, and their performances (P) are linked and act upon each other. The visual representation of the model is a spiral—or rather two superimposed spirals—showing the prospective and retrospective elements in the I-C-P triad, consisting of a number of cycles, which may range from 1 to n (Tyler 1978: 137).

The I-C-P model illustrates what we have emphasized above: cultures are interactive, autopoetic, self-organized configurations. They are emergent, instrumental adaptations characterized by rhythmic, sequential, oscillating iterations manifested as transitions in phase space where each state is new and all states are bound together by resonance, tuning, and feedback. Phases are dissipative, responsive to emergent, interactive features that function reflexively as both constraints and telos. The model has a dialectical form in which components are simultaneously cause and effect, and all components are co-constructed, co-dependent, and co-determined.

Following Wilhelm von Humboldt, the Rhetoric Culture project emphasizes the ontological unity of oratio and ratio in logos and insists that reason is inseparable from language; thought inseparable from speech. The “I,” as von Humboldt has said, critically depends on the “You.” The “I” needs the “You,” whose power of thought radiates back to the “I,” and vice versa. As the “I” and the “You” engage in discourse, their very use of language presupposes the other’s power of thought, although both also know from experience the dangers of misunderstanding inherent in the use of language. We humans simply have no other choice than to engage in inward and outward rhetoric, for between the thought of the “I” and the thought of the “You” there is “no other mediator but language” (1995: 24).

Both inward and outward rhetoric are thus constitutive of culture, as Jean Nienkamp has explored more fully in her historical sketch of the modalities and relationships between internal rhetorics and public rhetoric or oratory. She provides striking examples of internal rhetoric in very early Greek texts such as the Iliad, which are of particular import here. Thus, we hear Odysseus talk to himself in the midst of battle:

Now Odysseus the spear-famed was left alone, nor did any

of the Argives stay beside him, since fear had taken all of them.

And troubled, he spoke then to his own great-hearted spirit:

‘Ah me, what will become of me? It will be a great evil

if I run, fearing their multitude, yet deadlier if I am caught alone;

and Kronos’ son drove to flight the rest of the Danaans.

Yet still, why does the heart within me debate on these things?

Since I know that it is the cowards who walk out of the fighting,

but if one is to win honor in battle, he must by all means

stand his ground strongly, whether he be struck or strike down another.’

While he was pondering these things in his heart and his spirit.

(italics by Nienkamp 2001: 12)

Nienkamp stresses that this example shows how rhetoric is an almost timeless general human disposition, and she applauds Susan Jarratt for arguing that, “mythic discourse is capable of containing the beginnings of a ‘rhetorical consciousness’ ” (Jarratt 1991: 35). Furthermore, she distinguishes between an orthodox position that restricts the definition of rhetoric to oratory, and a position that sees “all human meaning-making as rhetorical,” and which she calls “expansive” (Nienkamp 2001). Proponents of the latter view such as Lloyd Bitzer and Edwin Black (1971: 208) include in rhetori...