eBook - ePub

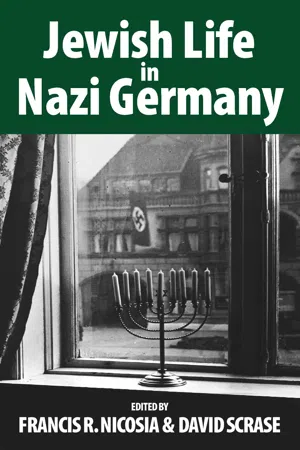

Jewish Life in Nazi Germany

Dilemmas and Responses

This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jewish Life in Nazi Germany

Dilemmas and Responses

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

German Jews faced harsh dilemmas in their responses to Nazi persecution, partly a result of Nazi cruelty and brutality but also a result of an understanding of their history and rightful place in Germany. This volume addresses the impact of the anti-Jewish policies of Hitler's regime on Jewish family life, Jewish women, and the existence of Jewish organizations and institutions and considers some of the Jewish responses to Nazi anti-Semitism and persecution. This volume offers scholars, students, and interested readers a highly accessible but focused introduction to Jewish life under National Socialism, the often painful dilemmas that it produced, and the varied Jewish responses to those dilemmas.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Jewish Life in Nazi Germany by Francis R. Nicosia, David Scrase, Francis R. Nicosia, David Scrase in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia ebraica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

CHANGING ROLES IN JEWISH FAMILIES

Marion Kaplan

HAVING ACQUIRED FULL CITIZENSHIP AND middle-class status in the latter part of the nineteenth century, most of Germany’s Jews felt comfortable and safe enough to consider Germany their Heimat, or home. They married, or intermarried, in Germany, built their businesses or careers there, sent their children to its excellent public schools, and planned their families’ futures in Germany. The Nazi onslaught against their rights, their livelihoods, and their social interactions with other Germans staggered them. Their normal lives and expectations overturned, Jewish families embarked on new paths and embraced new strategies that they would never have entertained in ordinary times. For women, this meant new roles as partner, as breadwinner, as family protector, and as defender of their businesses or practices, roles that were often strange to them, but ones that they had to assume if they were to save their families and property. For children, this included growing up fast—too fast for many—in order to run the gauntlet of Nazified (Germans used the term Gleichschaltung) schools and to minimize the strains on their already anxious parents. Finally, the men’s world as they had known it changed at a dizzying pace as they lost jobs and could no longer adequately or even barely protect or support their families or even themselves. This essay will look at several ways in which families, and the individuals in them, adjusted to extraordinary times.

Family as Haven?

Jews had, since the late nineteenth century, limited the size of their families, but they quickly reacted to their deteriorating political and financial situations by lowering their birthrate even more drastically.1 Women underwent private and highly illegal abortions, fearful of endangering themselves and their doctors.2 This seems to be a clear indication that Jews no longer saw a future for their children in Germany and also that, despite early hopes that the Nazi regime might fall, some planned to emigrate, waiting, perhaps, to give birth to children in places of refuge. The birth rate also tells us that the attempts of Jewish communal leaders3 to foster a “return to the family” in this era, whether through the press, sermons, or reprints of Moritz Oppenheim’s “Pictures of Old Jewish Family Life,”4 did not resonate among harassed couples.

The family as “haven in a heartless world”5 simply could not hold up. A teacher noted: “It would be wrong to say that the parental homes disintegrated, but in many cases home life was cheerless and full of troubles.”6 This was, perhaps, inevitable; their world was shrinking and Jews spent more and more time at home mulling over their situation7 and getting on each other’s nerves.8 Under these circumstances, Jewish women were to take on the old/new role of what feminists have called “emotional housework,” that is, making the household a more pleasant environment. Leaders urged women to preserve the “moral strength to survive” and held up Biblical heroines as role models.9 No longer focused on Victorian notions of making the home an “island of serenity” for the bourgeois husband, spokesmen and women urged housewives to exert a calming influence on the entire family, since: “the tension that we have all been living under … has made people irritable; the constant struggle against attacks makes them aggressive, intolerant, impatient.”10

The Jewish press also gave mothers the job of making their children proud of being Jews, a task that proved particularly difficult among children who simply wanted to fit in with their peers.11 Finally, parents still tried to protect their children from worries and, accordingly, often grew silent when younger ones were in the vicinity. One woman wrote: “We knew too little. I grew up in a time when the world of children was clearly separated from that of the adults … Parents did not talk to children, especially not about their plans and worries.”12 Parental attempts to shelter their children may have met with only modest success. Even little Ruth Kluger knew what was going on as she pretended to sleep on the sofa in the living room: “Their secret was death, not sex. That’s what the grown ups were talking about.”13

The Job Situation for Men, Women, and Youth

As the Nazi government implemented its anti-Semitic legislation, Jewish men, in particular, lost their jobs and businesses, some as early as the “April Laws” of 1933. Suddenly, and despite limited options on the job market, many Jewish women who had never worked for pay needed employment. Some did not have to look far afield for jobs.14 Much like their grandmothers decades earlier, they worked for husbands or fathers who had to let paid help go. By 1938, a columnist noted: “We find relatively few families in which the wife does not work in some way to earn a living.”15 In fact, as early as 1934, the Jewish feminist organization, the League of Jewish Women, noticed: “Today the woman is not only the spiritual, but, unfortunately, often the material support of the family.”16 By 1938, Hannah Karminski, an officer of the League of Jewish Women, remarked: “The picture of a woman who supports her family’s basic sustenance is typical.”17 Moreover, large numbers of women and men retrained for the kinds of jobs still available in Germany or in countries of refuge, mostly in agriculture, crafts, home economics, and nursing.18

Did this massive change in economic conditions affect roles within the family? Yes, ever so slightly. The League of Jewish Women, for example, still regarded married women’s employment as a last resort, acceptable only in times of crisis.19 Working mothers still needed to wake their children and tuck them into bed: “The first and last look of the day must re-fuse the mother-child unit.”20 Despite new jobs and less household help, wives carried the lion’s share of household work. Jewish newspapers advised housewives to consider vegetarian menus because they were cheaper, healthier, and avoided, for some, the kosher meat problem. Although meat might be easier and more time-efficient to prepare, columnists advised women that their “good will [was] an important assistant in a vegetarian kitchen,”21 and newspapers printed vegetarian menus and recipes.22 After the Nuremberg Race Laws of September 1935, when many Jews lost any household help they might still have retained, the CV-Zeitung ran articles entitled “Everyone learns to cook” and “Even Peter cooks…”23 Husbands were requested to be less demanding and children, especially daughters,24 were asked to help out. During this particularly stressful time, writers did frown upon authoritarian behavior, even that by the “head of the family.” One writer asserted that such behavior stemmed from a time when “men and fathers were overvalued in comparison to women and wives.”25 In an era when Nazi ideology shrilly reaffirmed male privilege, with women relegated to “children, kitchen, and church,” (Kinder, Küche, Kirche), it was being called into question—but not overtly challenged—in Jewish circles. Thus, gender roles and privileges within the family were barely modulated. Why this was so is not difficult to explain.26 By proclaiming the crisis nature of women’s new position, Jews, both male and female, could hope for better times and ignore the deeply unsettling challenges to traditional gender roles in the midst of turmoil.

Children and teens, too, had to reconsider the kinds of jobs they might have in the future and some had to drop out of school to assist their families. One boy dropped out of school a year before his Abitur in 1937. The teachers had made life miserable for him, and his family’s financial problems did not allow him to continue either.27 Forced to re-evaluate their options, that is, to cut back on their former hopes and plans, many Jewish teens suffered the accompanying pain and disappointment that that caused. Moreover, family dissension grew when parents and children clashed regarding the vision each had of the child’s future. This seems particularly to have been the case between girls and their parents. One school survey in 1935 indicated that girls preferred jobs in offices or with children (such as a kindergarten teacher), whereas parents thought they should become seamstresses or work in some form of household setting. Parents were more likely to go along with boys’ choices of crafts or agricultural training, useful, for example, in Palestine. This tension must have been greater among girls who had high school educations than those who, only attending Volksschule, had lower expectations from the start.28 Moreover, if one excludes housework, the choices available to girls were far more limited—and hence, more frustrating—than those open to boys. Welfare organizations suggested sewing-related jobs, such as knitting, tailoring, or making clothing decorations, whereas boys could consider many more options, including becoming painters, billboard designers, upholsterers, shoe makers, dyers, tailors, or skilled industrial or agricultural workers.29 To make matters worse, parents seem to have preferred keeping girls home altogether, either to shelter them from unpleasant work or to have them help out around the house as paid help was let go.30 Ezra Ben Gershom described a concrete example of this kind of decision-making. With his oldest sister married, his father decided that he and his two brothers should receive vocational training and that their other sister should help their mother with housework.31

Women Represent the Family

Whether women had to work or not, they soon took part in public life far more than they had ever before. Increasingly, women found themselves representing or defending their men, whether husbands, fathers, or brothers. Many tales have been recorded of women who saved family members from the arbitrary demands of the state or from the secret police (the Gestapo). In these cases, it was always assumed that the Nazis would not break gender norms: they might arrest or torture Jewish men, but would not harm women. Thus women took on a more assertive public role than ever before.32 Some actually took responsibility for the entire family’s safety, a reversal of previous roles with their husbands. Liselotte Mueller traveled to Palestine to assess the situation there. Her husband, who could not leave his medical practice, simply told her: “If you decide you would like to live in Palestine, I will like it too.” She chose Greece. Her husband, older and more educated than she, would in other circumstances have been the decision-maker, but he agreed.33 Ann Lewis’ mother went to England to negotiate her family’s emigration with British officials and her medical colleagues. This decision was based on her fluency in English, her desire to meet members of her psychoanalytic profession, and her husband’s profession; as a medical doctor, he was not welcome in Britain, but she was. She, who had always been “reserved with strangers,” and for whom asking favors “did not come easily,” had to ask for letters of recommendation from British psychiatrists, and to apply to the Home Office for residence and work permits.34

Women had to call upon assertiveness they often did not know they possessed. After traveling to the United States to convince reluctant and distant relatives to give her family an affidavit, one woman had to confront the US Embassy in Stuttgart, which insisted that there was no record of her. She showed her receipts, but the secretary just shrugged. At closing time, she refused to leave, insisting that her mother’s, husband’s, and children’s lives depended on their chance to go to the US. She would spend as many days and nights in the waiting room as necessary until they found her documents. After much discussion, the consul ordered a search of the files and the documents were discovered. Today, her daughter refers to her mother’s actions as the “first sit-in.”35

Often facing danger and dramatic situations, women were required to have both bravery and luck. When her uncle was arrested in Düsseldorf, twenty-year-old Ruth Abraham hurried from one jail to the next until she found out where he was. Then, she appealed to a judge who seemed attracted to her. He requested that she come to his home in the evening, where he would give her a release form. Knowing that she risked a sexual demand or worse, she entered his home. The judge treated her politely and signed the release. She commented in her memoir: “I must add, that I look absolutely ‘Aryan,’ that I have blond hair and blue eyes, a straight nose and am tall.” Later, these traits would save her life in hiding; now, she was able to gain the interest or sympathy of men who did not want to believe that she was Jewish.36

The judge’s treatment of Abraham notwithstanding, traditional sexual conventions could be quite menacing. Despite increasing propaganda about “racial pollution” or “race defilement” (Rassenschande), Jewish women recorded frightening incidents in which “Aryans,” even Nazis, made advances toward them.37 One woman wrote of the perils of sexual encounters:

During the Hitler era I had the immense burden of rejecting brazen advances from SS and SA men. They often pestered me and asked for dates. Each time I answered: “I’m sorry, that I can’t accept, I’m married.” If I had said I was Jewish, they would have turned the tables and insisted that I had approached them.38

Overcoming the stereotypes of female passivity or sexual availability meant confronting gender conventions. These new roles may have in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Illustrations

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany: Dilemmas and Responses

- 1. Changing Roles in Jewish Families

- 2. Evading Persecution: German-Jewish Behavior Patterns after 1933

- 3. Jewish Self-Help in Nazi Germany, 1933–1939: The Dilemmas of Cooperation

- 4. German Zionism and Jewish Life in Nazi Berlin

- 5. Without Neighbors: Daily Living in

- 6. Between Self-Assertion and Forced Collaboration: The Reich Association of Jews in Germany, 1939–1945

- 7. Jewish Culture in a Modern Ghetto: Theater and Scholarship among the Jews of Nazi Germany

- Appendixes

- Contributors

- Selected Bibliography

- Endnotes

- Index