![]()

Part I

SAINTS AND SLAVES,

MOORS AND HESSIANS

![]()

Chapter One

THE CALENBERG ALTARPIECE

Black African Christians in Renaissance Germany

Paul H. D. Kaplan

Black Africans in Early German Art

During the reign of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1220–50), people of black African descent had begun to appear in German-speaking lands, and it did not take long for German artists—perhaps encouraged by Frederick’s display of his black African retainers—to start creating images of people of color.1 While Frederick’s black subjects were evidently Muslims, drawn from an exiled colony of Sicilians established by the Holy Roman Emperor at Lucera in Apulia, and the most direct depiction of blacks showing fealty to Frederick—an extraordinary fresco from the 1230s in a tower adjoining the monastery of S. Zeno in Verona2—is entirely secular in tone, the first German visual responses to black African identity are in the context of sacred Christian art. The great Magdeburg statue of St. Maurice, from c. 1240 to 1250, is evidently the first instance of this prominent saint being shown with the features and complexion of an African black, and recent scholarship has emphasized Frederick II’s important links to Magdeburg and even the imperial cast of monumental sculpture produced in that city during the second quarter of the thirteenth century.3 In any case, by the fifteenth century the black St. Maurice had become a standard element around Magdeburg and in adjoining parts of northern and eastern Germany, where the saint’s cult was strongly developed. There were also several lesser-known black saints of similar type, including St. Gregor Maurus of Cologne, whose likeness appeared in stained glass from the early 1300s onward.4

More than half a century earlier than the Magdeburg Maurice, Nicholas of Verdun’s Klosterneuburg Altarpiece (1181) had already depicted another pious figure with dark skin, though without the secondary physiognomic features (hair, nose, and lips) normally associated with black African identity. Nicholas’s figure is the Queen of Sheba, who acknowledges King Solomon’s wisdom.5 There are several other dark-skinned Queens of Sheba in late medieval German art, including a rather monumental example from the Baptistry of St. John in Brixen in South Tyrol.6 The queen is, of course, not a Christian, but her veneration of Solomon as described in the Jewish bible was understood as a prefiguration of the veneration of Christ by the Gentiles—a theme most directly addressed in the visual arts through the depiction of the story of the Three Magi (also known as the Three Kings) who adored the infant Jesus. The Africanization of one of these three prescient Gentiles in texts and images took place in the course of the later 1300s and early 1400s, with the key developments unfolding almost entirely in German and adjacent Czech lands.7 Though tales eventually emerged concerning the later baptism of the Three Magi, these figures were never quite treated as wholly Christian, but the African magus was soon associated with and said to be the ancestor of the contemporary Christian rulers of Ethiopia, collectively known to Europeans by the title of Prester John. By the late 1400s and early 1500s, the black African magus was everywhere in German art, and had become a relatively rare example of an iconographic motif that had spread from German painting and sculpture to nearly every other region of western Europe. Images of the black St. Maurice were also quite common in Germany around 1500, but were largely restricted to the provinces of Saxony, Brandenburg, and Pomerania. Very occasionally, an image of a black Maurice and a black magus would appear in the same work of art, as in Hans Baldung’s 1507 altarpiece made for display in some sacred space in Halle at the order of Ernst von Wettin, archbishop of Magdeburg.8 But this is an extremely rare case, since under normal circumstances the ecumenical point made by including a black saint was sufficiently articulated without this kind of doubling. The black magus, it is true, was often accompanied by African retainers of lesser status, and there are also a few images of Maurice appearing with his black “companions” (fellow soldiers of the imperial Roman army’s Theban Legion who were martyred with him). Both these groupings were intended to suggest that the pious African was a representative of a larger nation of people with similar complexions. However, the immediate juxtaposition of two separate pious blacks was generally avoided, and even Baldung made sure to place St. Maurice on the right wing of his altarpiece, at a significant distance from the black magus, who stands at the left margin of the central panel.

Ruth Mellinkoff, in her exhaustive study of depictions of “outcasts” in late medieval northern European art, cites a number of examples of black Africans and figures with at least certain elements of stereotypically black African appearance among those who mock, torture, or execute Christ and the saints. Mellinkoff has claimed that “[a] white-skinned society could tolerate a black magus and a black St. Maurice because they represented an abstract piety, but more often white society viewed blacks as physically and morally ugly, and therefore inferior and despicable.”9 But the pejorative visual images on which Melinkoff’s claim is based are themselves rather disconnected from the social reality of the era. Despite the numerous images of black Africans as executioners—including one in a drawing by Albrecht Dürer of The Martyrdom of St. Catherine from the early 1500s10—there is no real evidence that black Africans were employed in such capacities in Germany, and only one credible instance of this in Italy (from the 1460s).11 Both the black saints and the black executioners found in German art of this period are projections rather than reflections.

We do not, however, as yet really know much about the dimensions and the character of the black African population of Germany in the early 1500s, and it will take one or more historians with the determination of Kate Lowe (who has undertaken an in-depth and already fruitful investigation of black Africans in Italy during this era) to begin to clarify this matter. Dürer’s silverpoint Katharina of 1521 was created in Antwerp, and rendered an African servant to the Portuguese consul there; might Dürer’s other fine drawing of an African man, which bears the date 1508, have been based on a black resident of Nuremberg?12 It is impossible to say for sure, but an anonymous German altarpiece of c. 1515–20 (figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3), recently acquired by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, provokes this kind of question and provides more contextual evidence to help answer it. This work, known as the Calenberg Altarpiece, displays one of the most unusual combinations of multiple black African figures of any European Renaissance image.13

The Calenberg Altarpiece

Attributed to the still-anonymous Master of the Goslar Sibyls, and probably the handiwork of several collaborating painters, the Calenberg Altarpiece measures 99 x 276 cm, including both the central panel and the two wings. The wings are also painted on their exterior, with figures of Gabriel and the Annunciate Mary. The central panel depicts the mystic marriage of St. Catherine, observed by the saints James, Lucy, Peter, and Paul, along with the local duke and duchess and their court attendants. The inner portion of the right wing features the saints Cyriacus, Nicholas, and Anthony Abbot. The inner surface of the left wing is occupied by St. Maurice and five martial companions.

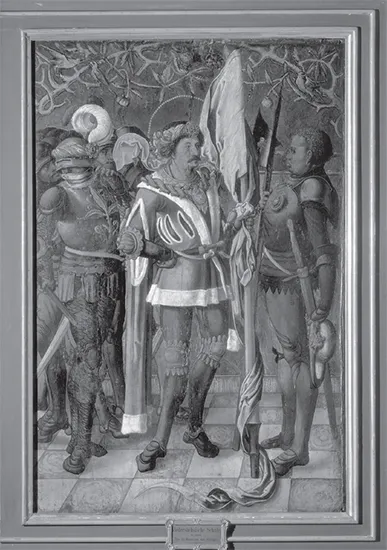

Figure 1.1. Master of the Goslar Sibyls (attributed to), Calenberg Altarpiece, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, c. 1515–20, detail of left panel (St. Maurice and Companions).

The left panel (see figure 1.1) contains several noteworthy features. It belongs, first of all, to a relatively small group of German images of Maurice with his companions, made during the second and third decades of the 1500s. Perhaps the earliest of these is a 1511 panel by Georg Jhener von Orlamünde, which forms part of the high altar in the church of St. Maurice in Halle.14 Halle had recently become one of the chief centers of the cult of Maurice thanks to Archbishop Ernst of Magdeburg (in office 1476–1513). The combination of sculptural and painted forms in the high altar was begun in the late 1400s. Maurice appears several times in sculpture and painting in the earlier phase of this project, but Jhener von Orlamünde’s contribution was a group of three black African companions to the saint. Two other compositions of c. 1520, from Lüneburg and (perhaps) Münster (now in the Goudstikker Collection), include not only the companions but also Maurice himself, and are therefore more closely related to the group in the Calenberg Altarpiece.15 This latter work (see figure 1.3), though it includes nearly three times as many companions as the Calenberg panel, was almost certainly inspired by it, and like the Calenberg panel it includes a range of complexions and physiognomies. The Goudstikker painting moves from very dark figures at the right to a medium-brown Maurice in the middle to comparatively light-skinned characters at the left, as if to acknowledge the variations of appearance among Africans. In the Calenberg panel, however, the companions all have emphatically dark skin, though only the soldier at the right, who wears no helmet and thus reveals all of his face, unquestionably displays each of the standard attributes of black African physiognomy as it was then understood by Europeans: dark complexion, full lips, wide nose, and tightly curled hair. By contrast, Maurice himself shows only a few of these traits: his skin is tawny and by far the lightest of the group, his nose is bony and projecting, his lips are hidden by a bushy moustache rarely worn by black Africans in European art, and his hair, though very curly, is much longer than the norm for European images of black Africans. Unlike the figure to the right, Maurice does not wear an earring, an embellishment that was one of the commonest ornamental attributes of black Africans in European artworks. There are in fact several images from this era of a black Maurice with white companions,16 but it is most unusual to find what I would call a North African or Mediterranean Maurice with black companions.

Does this imagery reflect the artist’s or the patrons’ discomfort with the concept of a major black African saint? If so, it would have been an unusual response in German lands, where the black magus as well as the black Maurice (and the black Gregor Maurus) had been familiar for some time. Calenberg, however, is some distance from the German epicenter of the black Maurice cult in Magdeburg and Halle, as Gude Suckale-Redlefsen’s mapping of black Maurice images makes clear.17 Indeed, the more obvious question about the Maurice panel of the Calenberg Altarpiece is why it was commissioned at all, given that the saint was not the special object of cult veneration in this region, west of Cassel at the edge of Westphalia and Lower Saxony.

The answer to this question lies, not unexpectedly, in the work’s patronage. The kneeling donor on the right side of the central panel (see figure 1.2) is Erich I (the Elder), Prince of Calenberg-Göttingen and Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (ruled 1495–1540), a noted military commander belonging to a relatively minor branch of the Welf clan.18 Erich’s more major claim to artistic fame is that he may be the handsome knight in armor at the side of Emperor Maximilian in Dürer’s Feast of the Rose Garlands of 1506; he was the emperor’s most trusted general for many years.19 In the Calenberg Altarpiece, however, he does not appear in martial dress. Neither he nor his blood relatives are especially connected to the cult of Maurice, but the situation is quite different with respect to his first wife, Catherine of Saxony, who kneels in what is actually a more honorific position—at the Virgin’s favored right hand—on the left side of the central panel. Catherine (1468–1524) was the first cousin of Archbishop Ernst of Magdeburg, who, as we have already seen, promoted the cult of the black Maurice in Halle (as well as Magdeburg), and who commissioned both Hans Baldung’s altarpiece with Maurice and Jhener von Orlamünde’s panel with Maurice’s black companions.20 In 1521, Catherine’s brother Duke Henry the Pious of Saxony named his newborn son and eventual successor Maurice.21 Catherine and her entourage, rather than her husband Erich, occupy the zone that adjoins the St. Maurice panel at the left. A chronicler of 1584 informs us, in fact, that it was Catherine who had commissioned not only this altarpiece but also the Calenberg castle chapel on whose high altar it was installed.22 Oddly enough, Duke Erich seems to have had a taste for spouses whose relatives were devoted to Maurice; after Catherine’s death in 1524, he immediately married Elizabeth of Brandenburg, the niece of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenbur...