![]()

Chapter 1

WINE LANDSCAPES AND PLACE-MAKING

The Burgundian vineyard is a complex patchwork and each site of production has its own identity and unique history. The fragmentation of terroir as well as the predominance of small wine holdings is one of the major features of the region. Landscape and social organisation are mutually reflective and interdependent and they are both marked by distinct hierarchies. The French wine industry is highly specialised in those areas where AOC prevails; around 85,000 wine holdings cultivate 780,000 hectares of vines.1 Burgundy holds a unique place because of its size and high concentration of small producers, with 4,100 family businesses cultivating 31,500 hectares. Most of these have been growing in size, increasing from 5.5 to 7.6 hectares on average between 2000 and 2010.2 The wine landscape has therefore witnessed a very slow process of concentration of landownership into the hands of the bigger family estates. Although there are examples of individuals or companies acquiring vineyards over the last decade, they remain in a tiny minority. In 2012, for example, the Château of Gevrey-Chambertin and its vineyard were sold to a businessman from Macau for 8 million euros causing a storm in the region in large measure because it was so exceptional. Compared to other wine regions, the Burgundian landownership structure and the scale of the vineyard have deterred any major external investments from international companies, and even the wealthiest local wine growers have tended to look outside Burgundy in order to expand. As Antonin Rodet, a prominent Burgundian négociant, noted during an interview in the French magazine Nouvel Observateur: ‘We are looking south because we are so crammed in our native Burgundy’.3 Other well-known négociants have sought to increase their portfolios by developing new vineyards in Ardèche (Latour) or by investing in California (Drouhin). This phenomenon has expanded to include well-known families of wine growers seeking to create new joint ventures elsewhere. The son of one of my oldest informers, who had been trained in Chile and Lebanon, has recently bought a vineyard in the south of France.

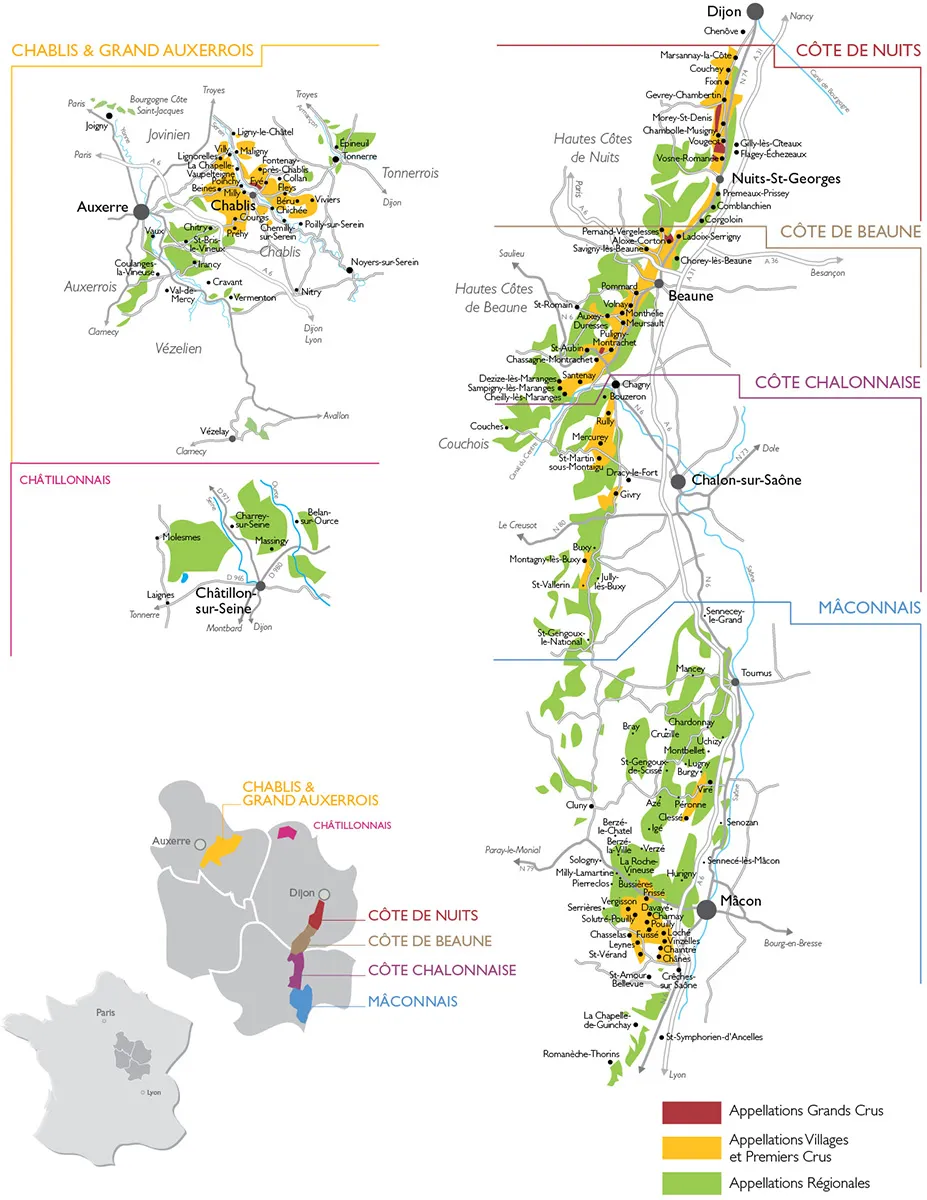

Figure 1.1 Burgundy and its vineyards © Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins de Bourgogne (BIVB) (www.vins-bourgogne.fr)

The Côte d’Or has, since the consolidation of the AOC legal system in the 1930s, been represented in the local iconography as a stable hierarchy of crus defined on the basis of their geographical orientation and exposition with the National Road 6 and the railway dividing what have historically been defined as quality wines from the rest. The hills and slopes are central to the quality argument in global viticulture and along the sixty kilometres between Dijon and Saint-Aubin a myriad of crus are dispersed. The term cru has a complex etymology and it derives from French cru, ‘vineyard’, literally ‘growth’ (sixteenth century), from Old French crois (twelfth century; Modern French croît), from croiss, stem of croistre, ‘growth, augment, increase’, and ultimately from Latin crescere, ‘come forth, spring up, grow, thrive’ (see crescent). In the Côte d’Or, the cru is the equivalent of the AOC and of a particular taste historically associated with the cru which might include different plots blended together when the wine is made.

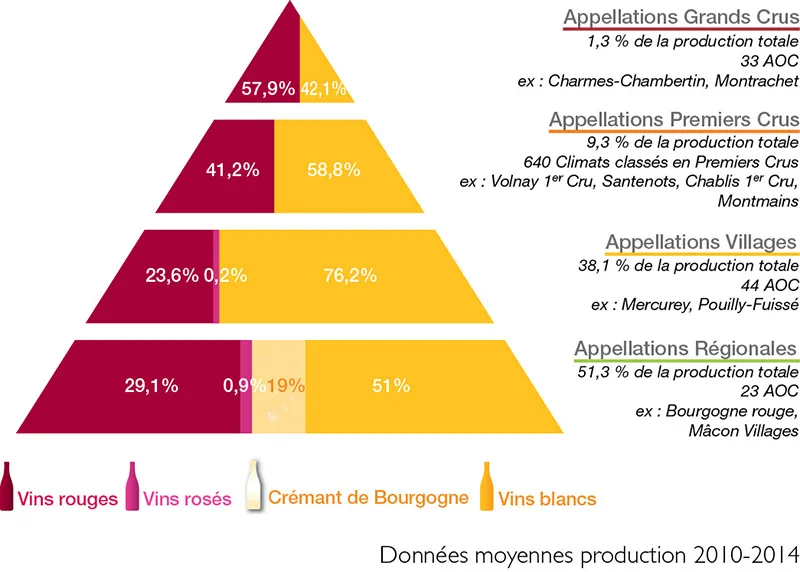

Despite its fragmented and heterogeneous nature,4 what has always been compelling about the Burgundy story as a whole is its ability to resonate with consumers on several levels. At the macro-level the wine growing area encompasses the emblematic regional name ‘Burgundy’ and on a micro level it is presented as a list of villages from Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune and the other major sites of production such as the Hautes-Côtes, Chablis, the Auxerrois, the Côte Chalonnaise, the Mâconnais, the Beaujolais and Pouilly-Fussé. In terms of volume, Burgundy produces 200 million bottles each year, covering over 100 different AOCs and representing only 0.5 per cent of the world’s total wine production.5 As a wine region, Burgundy is a complex puzzle which can be read from the websites dedicated to the region or the many ways in which local guides invite the visitor to explore its vineyards. Usually the encounter is accompanied by a range of sensations in which diversity, history, culture, tradition and tastes all contribute to the distinctiveness of the place. The historical investment is part of the story of place-making and no short cuts can be taken when trying to ‘understand’ Burgundy. The experience goes against the grain of contemporary society and culture with its diminishing attention span. Time is of the essence here. History and culture become embedded in the reading of the Burgundian vineyard, contributing to the resonance of authenticity in terms of the tourist’s experience of the site. From the Cistercians to the Dukes of Burgundy, the reputation and notoriety of the place has been cultivated for centuries through the selling of distinctive village names to European courts, wealthy elites and, more recently, the global consumer.

Figure 1.2 The geography of crus © Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins de Bourgogne (BIVB) (www.vins-bourgogne.fr)

Burgundy’s geography and landscape have played a major role in establishing the reputation of the place and acting as long-term markers of quality, not on account of their aesthetic value, but because of the historical resonance of the site and its wines. After perusing the literature devoted to the region, it is clear that the wine landscape was rarely seen as an attractive feature of the place. Gilles Laferté (2011) even argues that the region was perceived as a site of historical interest but not as picturesque. In his book, Terroir, James Wilson (1998: 108) describes Burgundy as an area where wines are produced on hills and slopes along the western side of the Saône Valley. For the most part the relief is modest, the plateaux of the Côte d’Or being only 500 feet (115 metres) above the valley whose elevations average about 725 feet (220 metres).

According to Wilson (1998: 108), the landscape is characterised by a narrow band of scarps, fault blocks and hills with rocks dating back to the Jurassic and Triassic periods and basement granites exposing Paleozoic rocks, schists and old volcanic intrusion. Variations in the crust resulted in different structural styles and landforms creating four geologically defined viticultural compartments: the Côte d’Or, the Châlonnais, the Mâconnais and the Beaujolais. Structurally the Côte d’Or is one long north-south fault scarp, broken only by combes and a few small river valleys. Thus the Côte d’Or vineyards are characterised by a long and narrow hillside facing hilly valleys, which are fortuitously protected from the worst aspects of the continental climatic conditions. According to Jean-Pierre Garcia (2011: 11–12), the soil of the vineyards is predominantly clay and limestone, although in fact it is much more varied following faults and localised land movements. This combination of landforms, soils and micro-climates forms a multitude of diverse micro-territorialised natural sites. For most commentators, these conditions have shaped wine production and were exploited by the Burgundians who developed historically small-scale ‘gardening viticulture’.

If the geological interpretation gives a sense of how the landscape is constituted, the anthropological perspective adds a very different dimension to our understanding of the wine landscape and local wine culture. My first encounter with the vineyards as a landscape and site of production dates back to the 1980s and to my years as a doctoral student conducting an ethnography of the grands crus. Having been born in Burgundy, I felt like many of my contemporaries that the vineyards were there and had always been there, but there was little aesthetic discourse or pleasure associated with their presence. The vineyard was mainly defined as a space for long walks or strolls on Sunday afternoons. Yet it was first and foremost a productive space for the local wine growing community. The landscape was largely fragmented, running in parallel with the nineteenth-century railway network and the more ancient National Road 6 which helped to form a barrier to further viticultural expansion. If today you were to drive south from Dijon to Santenay, along this road, most of the vineyard would be located on your right-hand side, visually presented as a tapestry or a patchwork of small vineyards assembled together and organised around a series of densely populated traditional Burgundian villages.

The local architecture has a chocolate box feel, with a series of quintessential French villages complete with church, châteaux and mairies. A sense of bustling activity defines these communities, there are still a few shops, and it is easy to meet the locals when walking around the streets. Wine production requires a workforce and these villages are characterised by the calendar of viticultural activities, from the hectic and noisy time of the autumn harvest to the more rhythmic winter and summer months which are punctuated by periods of intense labour. A sense of time dominates the wine landscape and the long-term occupation of the site is apparent from the monumental architectural presence of religious icons such as the Hospices de Beaune or the Clos de Vougeot as well as the smaller estates of generations of vignerons incarnated by stone walls and cabottes (small stone shelters) and the many walled clos.

It is only relatively recently that an awareness of the local landscape has taken centre stage in the context of the application for UNESCO World Heritage status (see Chapter 8). The prominence of landscape in heritage processes administered through the UNESCO has given a new meaning to viticultural landscapes and invested them with a political and cultural resonance. In 2006, for example, the United Nations deemed wine so integral to human history that it created and endowed an international chair for wine culture and tradition in Burgundy, which, revealingly, was given to a female climatologist specialising in the physical rather than the social or cultural aspects of the subject. Brock University in the USA and its CCOVI (Cool Climate Oenology and Viticulture Institute) was part of the driving force behind the creation of the chair. Proposed and spearheaded by the University of Burgundy and supported by CCOVI-Brock University, the Chair for Wine and Culture was established by UNESCO after much coordinated strategic lobbying.6 This facilitated, as a result, deeper engagement with the concept of cultural landscape and how it could be more productively understood by local communities. Wine landscapes have therefore become inscribed in a broader set of frameworks, combining a wide range of characteristics from the historical formation of local viticulture to legal definitions of denomination of origin and the collective sense of ownership attached to them. It is now a fundamental part of the new heritage strategies put in place to refine the distinctiveness attached to specific sites in the global world of wine. This chapter seeks to engage with the complex process of making sense of wine landscapes and locating these understandings and engagements within a broader ‘politics of scale’ and ‘politics of aesthetics’, which mesh local and global together in a process of reflexive imbrications defined as a careful and selected process of elements which are then adopted and translated into the local context to be in turn projected onto the global wine market.

Place-Making and Wine

According to Glenn Banks (2013: 2) the new geography of wine is marked by diversity and distinction in terms of production arrangements and technologies, cultural meanings and understandings, and the resulting landscapes and communities. If Burgundy was a precocious example of place-making around wine, with its distinctive culture, folklore, architectural and historically emblematic heritage, as well as a model of hospitality which was already based on conviviality and sharing, it is only with the recent UNESCO application that a shift has taken place, recasting some of the global references linking place to taste by fossilising and historicising the site of production, which is presented as a stable, trustworthy and reliable place. Rather than competing with New World Chardonnay or Pinot Noir, Burgundy seeks to reinforce its image as a distinct elite product, with its Montrachet or Clos de Vougeot having a very different historic, geographic and cultural resonance associated with its newly adopted climats.7 The successful UNESCO application will enhance and consolidate the identification between product and place of what is already defined as the ‘lien au lieu’ (link to a location). When drinking a Puligny-Montrachet Premier cru Les Pucelles,8 one should be able to visualise on the map the precise place of origin of the product, a small plot located on the hill. This strategy, which is similar to that developed in the luxury goods industry, emerges at a time when frauds in the wine industry are commonplace.9

The recent scandal of Rudy Kurniawan, who was arrested at his home in suburban Los Angeles and charged with what may ultimately go down as the wine crime of the century, is a case in point. Kurniawan was a thirty-five-year old Indonesian-born collector who, in the early 2000s, seemingly out of nowhere, became the biggest player on the fine-wine market, buying and selling millions of dollars worth of rarities. Kurniawan presented himself as a wine lover and the collector of rare bottles, who started to buy some of the most prestigious wines regularly at high prices. He then started to sell them, as well as other counterfeit bottles, through the same network of auction houses and some buyers trusted him sufficiently to pay up to one million dollars for the most precious vintages available. It was when the Burgundian wine grower, Alain Ponsot, was contacted by one of his friends, an American lawyer, who informed him that some of his wines from 1945, 1949 and 1962 were being sold at an auction, when the label did not exist before 1982, that the fraud was revealed. More than 4,700 bottles of counterfeit wines were discovered along with some authentic grands crus.

In the current global wine context, where all the traditional divisions in terms of viticultural practices and wine definitions seem to blur under the pressure of standardisation and homogeneisation, authenticity becomes a crucial area for differentiation (Barrey and Teil 2011). The significance of place in contemporary wine production is increasingly characterised by ‘place-based’ forms of marketing (Banks 2013: 3). In Burgundy the connection between history, quality and place-making has been a constant reference in the ways that place has been marketed and it is only recently with the UNESCO campaign that the region has reassessed its powerful terroir story. There is nothing new about sudden and often quite profound rethinking of what defines Burgundy and its wines. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the AOC system emerged as a response to crisis. As for the recent invention of the climats de Bourgogne, that owes much to the consequences of what is described as fast capitalism and globalisation. Both periods are revealing of how Burgundy has negotiated difficult times and shown an ability to reposition itself in the global world of wine.

The 1930s were characterised by a period of intense economic restructuring of the wine industry in France. From the inter-war period, a regionalist movement of tourist development and gastronomy strongly influenced the construction of the image of the Burgundy region and its wines (Laferté 2006). During that period, tourism was no longer considered simply as the discovery of monuments and natural sites, and agricultural and viticultural folklore took on a new importance. Meanwhile, local cuisines became regionalised and were promoted as identity markers. Tourism and gastronomy acted as strategic levers, promoting the revitalisation of rural areas. This shift was made possible by the development of mass ownership of the automobile, as evidenced by the history of the Michelin guide. Viticulture was even more profoundly affected by the creation in the 1930s of the AOC system, emphasising the origin of wines which came to constitute a new standard of quality, and required the education of consumers through the promotion of these new appellations. As part of this process, Burgundian viticulture was advertised through a largely invented wine culture based upon folklore and festivities featuring its wines and gastronomy, as part of a strategy of employing local heritage at a time of acute economic crisis (Jacquet 2009).

The creation of the Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin in 1933 and its chapters is one of the best examples of this touristic and patrimonial enterprise; the touristic Route des grands crus was created at the same time (1934) as well as the wine auction at the Hospices de Beaune (1921) and the Paulée de Meursault (1923) which all became festive occasions for both the locals and their clients. What they have in common is an attempt to create a new reading of place constructed around a folkloric tradition and the convivial and exuberant celebration of wine (Laferté 2011). The desire to promote Burgundy as the natural home of the gourmet contributed to the development of regional agricultural products as well as viticulture. The creation of a museum dedicated to wine heritage and culture is particularly evocative of the dynamics of heritage focused upon Burgundian viticulture which was led by actors external to the wine industry. Beaune was the first town in France to open a museum completely dedicated to viticulture, the Burgundy Wine Museum, established in 1938 and housed since 1946 in the fo...