eBook - ePub

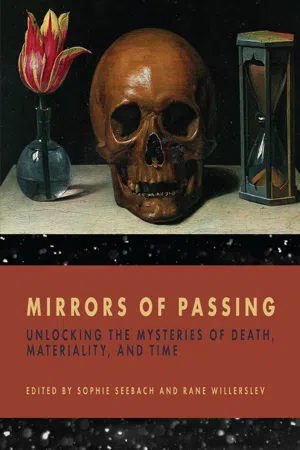

Mirrors of Passing

Unlocking the Mysteries of Death, Materiality, and Time

This is a test

- 326 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mirrors of Passing

Unlocking the Mysteries of Death, Materiality, and Time

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Without exception, all people are faced with the inevitability of death, a stark fact that has immeasurably shaped societies and individual consciousness for the whole of human history. Mirrors of Passing offers a powerful window into this oldest of human preoccupations by investigating the interrelationships of death, materiality, and temporality across far-flung times and places. Stretching as far back as Ancient Egypt and Greece and moving through present-day locales as diverse as Western Europe, Central Asia, and the Arctic, each of the richly illustrated essays collected here draw on a range of disciplinary insights to explore some of the most fundamental, universal questions that confront us.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Mirrors of Passing by Sophie Seebach, Rane Willerslev in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Death in Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Death’s Time

CHAPTER 1

The Time of the Dead

Anthropology, Literature, and the Virtual Past

What Do We Know?

“But what do we really know of the dead and who actually cares?” asks Nick Cave in his song “Dig, Lazarus, Dig” (2008), which reimagines the biblical Lazarus as an outcast turned junkie, unwillingly restored to life and wandering the streets of present-day San Francisco and New York. One answer to the question posed by Cave’s song (and suggested by the fate of its protagonist) is: a lot less than we once did. Such at least has been the claim of some still influential versions of the story of modernity. From Friedrich Schiller and Max Weber’s “disenchantment of the world” to Jean Baudrillard’s more recent “extradition of the dead,” the process of becoming modern, assumed to be concomitant with, among other things, industrialization, urbanization, the colonial expansion of Europe, and the global diffusion of capitalism, has been understood, repeatedly, in terms of a severed or attenuated relationship between the living and the dead (Baudrillard 1993; Weber 1949, 1976). If the so-called modern period, with its social upheavals, its armed conflicts, its military technologies, and its mass media, has produced not only death but also the spectacle of death on an unprecedented scale, this has been accompanied, so the argument goes, by a corresponding diminution in the social presence accorded to the dead. Take, for example, the eminent French historian Philippe Ariès, who, in his magisterial history of Western attitudes to death, contrasts what he calls the “tame death” of the early Middle Ages, when death was viewed as a culmination and thus an accepted part of life, with the “invisible death” of modernity, which is characteristically enacted in the confined and sequestered spaces of hospital wards, hospices, and mortuaries, a development that he sees as indicative of modern Europeans’ increasing unwillingness to extend any sort of collective recognition to death (Ariès 1982: 5–28, 559–601).

In seeming contrast, much past anthropological scholarship has focused on societies in which death and the dead appear to have retained a more conspicuous and acknowledged presence in the form of, for example, death rituals, mortuary rites, sacrificial killings, or offerings to ancestors. Nonetheless, the analytic lexicon of many such studies reveals what is, arguably, a no less characteristically modernist squeamishness in the face of death, offering contextually based explanations whereby death practices are treated as effects or epiphenomena of other social institutions, thus voiding simultaneously both the claims of local or indigenous understandings of death and the possibility that death might afford a vantage point from which to challenge or defamiliarize such received categories as social structure or the binaries of “nature” and “culture” (Seremetakis 1991: 14). Among Western European nation-states, Ireland, notably, has often been viewed as an exception to the supposed world-historical trend toward the elimination of the dead from collective life, being characterized instead in terms of an excessive or anachronistic attachment to the dead. The Elizabethan poet and colonist Edmund Spenser, writing in 1596, complained that the Irish were given to engaging in excessive lamentations for their dead, “ymoderate wailings” that he took as indicative both of a lack of civility and a residual paganism (Spenser 1934: 72–73). Four centuries later, a controversial study by Nina Witoszek and Pat Sheeran (1998) would criticize the “funereal culture” of Irish literature, past and present, for its alleged morbid fixation on the past and corresponding unwillingness to engage the present and future. It is tempting, but too easy, I think, to dismiss such characterizations as tropes of colonial discourse, lingering, in the latter case, into the postcolonial present. Instead, as the twenty-first century enters its second decade and the suspicion dawns (or perhaps it dawned long ago?) that none of us has, in Bruno Latour’s phrase, ever been truly modern, the predilection for death so frequently attributed to the Irish may present the opportunity to pose a different set of questions (Latour 1993).

In this chapter, I aim to do more than reclaim death as presence within the history of Ireland and of modernity, a move that, at the very least, runs the risk of restating the glaringly obvious. Rather, I propose to claim that death—and the dead—are an indispensable and constitutive component not only of cultural memory, but also of the very texture of our—or, indeed, any—being-in-the-world. As such, the dead can never be truly left behind, even if we as a society or even as a species decline to acknowledge their presence. To affirm the presence of the dead, however, requires the radical suspension of the linear chronology underpinning the temporal order of modernity, to which many of anthropology’s extant explanatory frameworks remain tacitly or explicitly indebted. Anthropology, I suggest, stands to learn not least from literature about alternative ways of conceiving and expressing time that might facilitate an engagement with the dead as something more than beliefs or representations generated out of social relationships among the living. Literature deals with the dead not only as subject matter (as anthropology has often claimed to do), but is also able to manifest their ineradicable presence no less effectively through its engagement with the materiality of its own medium, the phonic and rhythmic substance of words, through which the sounds and vibrations of the world are distilled into intelligible discourse, and which continue to murmur to potentially disruptive effect alongside language’s meaning-bearing functions. I propose that if literature is able not only to speak about the dead but also to enable the dead to speak, it does so by calling attention to the material being of language in a manner that cannot be reduced to the expression of cultural meaning. Literature, that is, makes the dead matter.

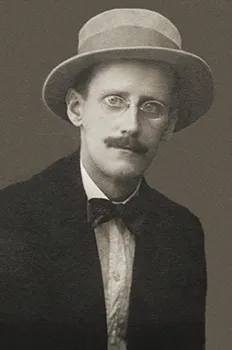

I take my cue from (arguably) Ireland’s greatest twentieth-century writer, James Joyce, a writer whose work is at once unimpeachably “modern” in its subject matter and pursuit of formal and linguistic experimentation and yet suffused at the same time by the presence of the dead (Figure 1.1). What I undertake is less an explication of Joyce’s writings than a series of reflections that takes Joyce’s work as its starting point and returns continuously to it, while pursuing, at the same time, some comparative anthropological tangents less frequently explored in mainstream Joyce scholarship.

A Winter’s Tale

For reasons that will, I hope, become clear, much of what I have to say in the following pages can be characterized as a winter’s tale. Accordingly, I begin with another, better known and more celebrated winter’s tale—Joyce’s short story “The Dead,” written in Trieste in 1907 and first published in 1914 as the concluding story in the volume Dubliners (Torchiana 1986). The story takes place in Dublin, Ireland, in early January, some time around the beginning of the twentieth century, during the final decades of British rule. The Irish nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell has been dead since 1891, and the events of the Easter Rising of 1916 and the independence struggle that followed in its wake lie more than a decade in the future. The scene is the upper floor of a house on Usher’s Island on the south bank of the River Liffey. The occasion is the annual dance hosted by the Misses Morkan—two elderly spinsters, Aunt Kate and Aunt Julia, and their niece, Mary Jane. Outside snow is falling, covering the city and, as we later learn, the whole of Ireland, the heaviest snowfall in thirty years, according to the newspapers. As the snow continues to fall, the focus of attention indoors is on the Misses Morkans’ nephew, Gabriel Conroy, a “stout, tallish,” bespectacled young man, by profession a teacher of languages and a graduate of what was then the Royal University (now the Dublin campus of the National University of Ireland). At the opening of the story, Gabriel arrives, somewhat belatedly, in company with his wife, Gretta, who is, we are soon to learn, a native of County Galway, on Ireland’s western coast. They have left their two children at home in the middle-class suburb of Monkstown in the care of a servant and are planning to spend the night at the Gresham Hotel in the city center. The evening is to prove a fateful one for Gabriel. Things get off to a bad start when a casual inquiry about the servant, Lily’s, matrimonial prospects draws the bitter retort: “The men that is now is only all palaver and what they can get out of you!” (Joyce 1992: 211). Disconcerted, he begins to worry that his after-dinner speech will, likewise, prove a failure and that an allusion to the poetry of Robert Browning that he plans to include will fly above the heads of his listeners. There follows another uncomfortable altercation, this time with his colleague and university contemporary, Molly Ivors, who chides him for writing a literary column for the Unionist newspaper The Daily Express and for declining to join a planned excursion to the Irish-speaking Aran Islands, preferring instead a cycling tour of Continental Europe. Her cultural nationalist rebuke that he knows nothing of his own land and people prompts him to his own outburst: “I’m sick of my own country, sick of it!” resulting in Miss Ivors’s premature exit from the gathering (ibid.: 222–23). It is after the party, however, when he and Gretta are alone in their room at the Gresham, that Gabriel is confronted by the night’s most disturbing revelation, a revelation about his wife’s Galway past that propels the story toward its celebrated ending. In an outburst of tears, Gretta tells him that a song, “The Lass of Aughrim,” sung earlier in the night by one of the other guests, has reminded her of a young man whom she knew and loved as a teenager. The young man in question, Michael Furey, was an employee of the local gasworks. In response to her husband’s initially jealous questioning, she reveals that Michael Furey has been dead for many years, a victim of the tuberculosis that at the time claimed as many as ten thousand lives annually in Ireland, and that, as she puts it, “I think he died for me.” It was, she relates, the beginning of winter, and she was about to leave her grandmother’s house in Galway to attend a convent school in Dublin. Michael Furey was ill in his lodgings and was forbidden to receive visitors, “so I wrote him a letter saying I was going up to Dublin and would be back in summer, and hoping he would be better then.” The night before she left, she was in her room packing up her belongings when she heard gravel thrown against the window. Unable to see out on account of the rain, she ran downstairs and found Michael Furey shivering under a tree in the garden. She begged him to go home, but he declared that he no longer wanted to live. Finally, she convinced him to return to his lodgings. Then, a week after arriving at the convent in Dublin, she learned that he had died and was buried at Oughterard, his family home, a small town seventeen miles northwest of Galway. “O, the day I heard that, that he was dead!” (ibid.: 251–254).

Figure 1.1. James Joyce. Photograph by Alex Ehrenzweig, 1915. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

As the story ends, Gretta has cried herself to sleep. Gabriel, still awake, lies beside her on the bed, reflecting on his marriage and contrasting his own relationship with his wife with the death-defying passion of Michael Furey. Outside, the city and, indeed, all of Ireland lies under a blanket of snow. What follows is, arguably, one of the most widely discussed passages in modern Irish literature, one that decisively transfigures the naturalistic surface both of the story itself and of the collection as a whole:

Generous tears filled Gabriel’s eyes. He had never felt that himself towards any woman, but he knew that such a feeling must be love. The tears gathered more thickly in his eyes and in the partial darkness he imagined he saw the form of a young man under a dripping tree. Other forms were near. His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself, which these dead had one time reared and lived in, was dissolving and dwindling.

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westwards. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, further westwards, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead. (Joyce 1992: 255–56)

The two paragraphs in question have been the subject of extensive critical commentary, much of it concerned with Gabriel’s seeming revaluation of his relationship to the West of Ireland, from which his wife hails and which he has so pointedly repudiated earlier in the story. I want to draw attention here, however, to two less frequently remarked features of the passage quoted. First, I want to note that the dead make their appearance in the guise of a crowd or multiplicity—“the vast hosts of the dead”—and that the named and individuated figure of Michael Furey emerges from and is, finally, reabsorbed by this undifferentiated mass of the dead, just as the figures of Odysseus’s mother and, later, Tiresias emerge from (and recede into) the “multitude of souls” who throng about the sacrificial blood in Book XI of Homer’s Odyssey (a work that would later serve as the template for Joyce’s 1922 masterpiece, Ulysses).1 Second, I want to mark the seasonality of this concluding manifestation of the dead, the fact that it takes place at the close of the Christmas season, in midwinter, as signaled by the ubiquitous and much discussed snow that falls alike on all the living and the dead, imparting to the scene, at the same time, a certain unassailable, if elusive, materiality that the dead themselves, in their “wayward and flickering existence,” might otherwise seem to lack (Figure 1.2). Let me consider each of these aspects in more detail.

Figure 1.2. “Snow was general all over Ireland.” Photograph by D. Sharon Pruitt. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

The Invisible Crowd

Elias Canetti, in his study Crowds and Power, suggests that the so-called invisible crowd of the dead may be among the most ancient and the most universal of human imaginings: “Over the whole earth, wherever there are men, is found the conception of the invisible dead. It is tempting to call it humanity’s oldest conception” (1992: 47). Of these invisible dead, he writes that “generally it was assumed there were a great number of them,” and he proceeds to give, by way of illustration, an eclectic range of ethnographic examples: the Bechuana of South Africa, who “believed all space to be full of the spirits of their ancestors”; the Chukchi shamans of northeastern Siberia, with their “le...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction. Mirrors of Passing

- Part I. Death’s Time

- Part II. Materialities of Death

- Part III. Life after Death

- Part IV. Exhibiting Death, Materiality, and Time

- Index