![]()

CHAPTER 1

Youroumaÿn

“The first view of St Vincent’s is magnificent: its noble mountains rise in masses, each higher than the one before it; until the mountains of the centre, crowned with mists, seem to look down with majesty upon the subject hills around, which gradually decrease in height, until they approach the Caribbean Sea, whose deep blue waves fling their snowy foam, conch-shells, sponges, marine eggs, and white coral, at their feet. The fertile plains and vales are hidden by these mountains, which have perpetual verdure: yet, owing to the cultivation of their bases, sides, and even summits, and the ever-varying kaleidoscope of light and shade caused by the shifting clouds, the surface of this island has a singularly part-coloured appearance; and, when the traveller looks from its elevations, his eye is gratified with the sight of the Grenadines, which, although no longer fertile, are so beautifully placed and so fantastically formed, that they heighten in an eminent degree the beauty of the sea-view …”1

—EL JOSEPH, Warner Arundell, the Adventures of a Creole, 1838

Youroumaÿn. That was the name the Caribs gave to the island Europeans knew as St. Vincent—or at least that was how it was recorded by Adrien Le Breton, a Jesuit missionary who spent ten years living there at the end of the seventeenth century.2 No more than twenty-two miles from north to south and fourteen to sixteen miles wide, with fertile land to grow crops, woods to hunt game, and a surrounding sea abundant with fish, Youroumaÿn had everything that the Caribs needed. The mountain at its center is a volcano, responsible in the geological past for the island’s very existence, and from its flanks ridges extend down towards the sea dividing the land into a series of wooded valleys. Alongside the streams that flow down to the rugged coast the Caribs made their homes.

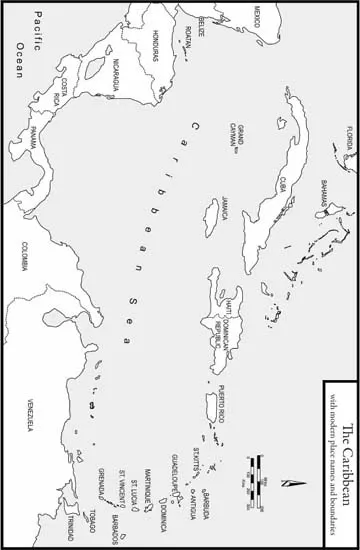

“The Island of St. Vincent is the most populous of any possess’d by the Caribbians,” asserted Charles de Rochefort, a Protestant pastor who visited the West Indies in the mid-seventeenth century. “The Caribbians have many fair Villages, where they live pleasantly, and without any disturbance.”3 Other lands were also home to Caribs at the time of their first contact with Europeans. The Caribs ranged over the whole island chain, stretching some five hundred miles from Grenada and Tobago in the south, through St. Vincent, St. Lucia, Dominica, Martinique, and Guadeloupe, up to Antigua and St. Christopher (St. Kitts) in the north. Trinidad was largely the province of Arawaks, and Barbados, it seems, was no longer permanently occupied. By the time that Rochefort was writing, though, the Caribs’ territory was already beginning to shrink in the face of European encroachment. At the turn of the eighteenth century St. Vincent was described as “the head-quarters of the Caribs.”4

To the outsider’s eye it seemed as if the topography of Youroumaÿn/St. Vincent was uniquely conducive to the Carib way of life. Le Breton wrote that “the fortunate complicity of the country astonishingly encourages the people’s frenzy for total independence … the island … is riddled with bays and hollows … [and] … offers each father of a family the opportunity to choose … his ideal site, far from any foreign constraint and completely safe … to lead his life exactly as he pleases with his wife, children and dear ones.”5 This spirit of independence was remarked upon by nearly all early European accounts of the Caribs. Jean Baptiste Du Tertre, a French soldier-turned-missionary in the West Indies in the 1640s, wrote: “No polity is seen among them; they all live in freedom, drink and eat when they are hungry or thirsty, work and rest when they please; they have no worries …”6

Adrien Le Breton spent more time among the Caribs of St. Vincent than any of these writers but he told the same story. “Even from the very beginning of their communal living, they were filled with hatred of not just slavery, but any form of injunction, authority or submission, to the extent that these very words themselves are unbearable to them. Yielding to someone else and obeying an order is for them the ultimate indignity. Even today, this explains the virulence of their total freedom. All of them are perfectly equal, and they recognise absolutely no official, chief or magistrate.”7 So although people speaking the Island Carib language and sharing the same culture lived on islands spanning hundreds of miles, there was no Carib state in the West Indies. No man, no chief, commanded beyond his immediate district, except in time of war.

Early descriptions tend to remark upon the Caribs’ health and vigor. Raymond Breton, a missionary of the Dominican order who was sent to the region by Cardinal Richelieu and who lived on the island of Dominica from 1641 to 1651, wrote, “they are of good stature and well proportioned, strong, robust, ordinarily fleshy, and healthy. … Their natural colour is sallow, strongly tanned. … Their hair is completely black. …”8 Rochefort thought them a “handsome well-shape’d people, well proportion’d in all parts of their bodies … of a smiling countenance, middle stature, having broad shoulders, and large buttocks,” adding that “their complexion is naturally of an Olive-colour.”9 They appeared to enjoy great longevity; various accounts suggested that Caribs frequently lived beyond a hundred years of age and that these venerable figures showed little of the stooped posture and wrinkled skin of old age. Rochefort claimed that it was common for Caribs to reach 150, although how he verified such a marvel is unclear (indeed, the Island Carib language had no words for numbers above twenty10). According to Raymond Breton, “Their long life must be attributed to their lack of care.”11

A Carib man might take as many wives as he could provide for and a profusion of wives and children was an indicator of status. The man would build each new spouse a house (which might even be on a different island) and little friction was reported among the various wives. Villages were typically based upon a single extended family headed by a male “chief” or “captain”12 and tended to be sited on rising ground to avoid still air and attendant mosquitoes. They also needed to be near rivers or brooks since the Caribs liked to bathe first thing every morning. The main building was called by the French a carbet, originally an oval structure that might measure sixty to eighty feet long by twenty feet and was thatched with roseaux (reeds) or latanier (palm fronds). It was here that the men ate, that guests were received, and that feasts were held. The women and children would generally eat in separate, smaller houses. The main furniture was in the form of wooden stools or tables with a woven top called a matoutou. All slept in hammocks (a Carib word).

Following their morning ablutions, the men would sit on a small stool while the women painted them with roucou, a red pigment derived from the seeds of the annatto tree, which as well as serving as an adornment helped to protect the skin from the sun and from insects. The women would then paint their own bodies. Facial piercings and feathers in the hair completed the look. Men might play on the flute while the women made breakfast. Ready to face the day, the men occupied themselves with fishing and hunting or, when necessary, felling trees. Land crabs and other shellfish were important elements of their diet but birds and small mammals such as the agouti might also be brought in. Their activities were not so intense that they did not allow time for them to “spend entire half-days sitting on top of a rock, or on the riverbank, their eyes fixed on land or sea, without saying a single word.”13 Although women were frequently described as slaves to their menfolk by Europeans, Raymond Breton observed sardonically that neither men nor women killed themselves through overwork. One of the Caribs’ preferred activities was visiting other communities near and far, occasions that were always marked by elaborate hospitality and celebration.

Women were busy near constantly, not just looking after the home and children but growing crops, preparing food and spinning cotton. It was noted that mothers cared for their offspring with great tenderness,14 even if one aspect of this seemed remarkable to outsiders: mothers would press their baby’s head between boards to create the characteristic Carib look of a backwards-sloping forehead. In clearings in the woods the women raised cassava (the root crop also known as manioc or yuca) in small gardens among the stumps of trees felled by the men. These provision grounds were moved from time to time as the soil became exhausted. Other vegetables, including beans, yams and other tubers, plus plantains and bananas were also grown. Fruit trees were often cultivated near the houses, with the pineapple particularly prized. Cassava was the Caribs’ indispensable staple but preparing it was a complex process, involving grating the tubers and straining the product through a tall sieve. “Their cassava press is a rather short wide pipe made of basket-work. After the manioc has been grated, the wet cassava meal is put into this pipe, which is then hung to a branch of a tree with a heavy stone tied to the bottom. This weight gradually pulls out the pipe till it is long and narrow and thus squeezes the water out of the meal.”15 Women made and cooked cassava bread (areba) fresh every day and juice from the plant was used with the addition of peppers and lime juice to make a hot, spicy sauce or broth called tumallen—Caribs loved spicy food. This versatile plant was also the basis for an alcoholic drink known as ouïcou, for which the women often masticated the cassava to speed the fermentation process (ouïcou prepared in this way was said to be “incomparably better”16). This drink was an important part of Carib feasts; indeed these events were known as ouïcous or later, after trade with the French, vins.

These carousals were frequent and drinking was at the center of Carib culture. Rochefort lists seven motives for a ouïcou: as a council of war; on a return from an expedition; on the birth of a male child; when a child’s hair is first cut; when a boy comes of age to go to war; when trees are cut to build a new house or make a garden; and at the launching of a new vessel. Men, women, and children might be present at such a feast. First the men, then the women, would dance, the latter shuffling their feet with one hand on their head and the other on their hip amid singing and flute playing. Most songs were about warfare; others dealt with birds, fish, and women.17 After much drinking, and smoking, the evening would often end in raised emotions and, as old grievances were recalled, violence. With no government, revenge was the principal instrument of justice and a ouïcou, with an antagonist’s guard perhaps lowered, was the perfect place to exact vengeance for some previous offence. If warfare was being contemplated it was up to the chief or “captain” hosting the ouïcou to persuade his guests to fight. Caribs always listened patiently to each other without interruption. After much drinking an old woman might harangue those present, reminding them of past injustices suffered at the hands of their enemies and previous acts of bravery. She might also brandish a body part, such as an arm, of a slain enemy from a previous war, smoked—boucaned—to preserve it. The captain hosting the ouïcou would then reiterate her arguments. A date a few days thence, ideally coinciding with the full moon, would be set for the war party to assemble. The man proposing the action was in command but only for the duration of the raid.

The Caribs had a reputation as fearsome warriors. Trained from boyhood, they were deadly with a bow in hand. “Not only do the Indians shoot straight, but they shoot so quickly that they can loose ten or a dozen arrows in the time it takes to load a gun.”18 It was claimed they could regularly hit a half-crown piece at a hundred paces. The Caribs sometimes poisoned their arrows with the sap of the manchineel tree.19 In time, following trade with the Europeans, they transferred their marksmanship to firearms. For close-quarters fighting Caribs wielded the boutou, a heavy, three-foot-long wooden club, often elaborately carved and decorated.

Before setting off, warriors donned war-paint, overlaying black pigment around the eyes and mouth, or in stripes all over the body. The raiding party traveled in large canoes, or pirogues, which might carry fifty or more men and were fitted with sails for travel between the islands (Caribs also used canoes—another Carib word—less than twenty feet long for fishing); a few women would be taken along to prepare food. The ideal mode of attack was by the light of the full moon or at daybreak, surprising the enemy in their hammocks. One tactic was to shoot flaming arrows into the dry palm leaf roofs of houses and then kill the fleeing inhabitants. Surprise was a key element of Carib tactics and if this was compromised the attack would often be abandoned. Battles rarely lasted beyond midday and determined resistance quickly disheartened attackers. The Caribs always took great pains to carry their wounded and dead from the field.

The Caribs told the early French missionaries who lived among them that their ancestors originally came from the mainland of South America. According to Adrien Le Breton, “It is absolutely certain” that the Caribs, or Karaÿbes, “originated among the people living not far off on the coast of the continent,”20 and it was a belief reported on other islands where Caribs spoke to European chroniclers. The Caribs referred to their kin on the mainland as Galibis.

Anthropologists suggest their ancestors originated in the continent’s Amazonian interior and migrated to the islands from the region of the Guianas. Archaeological evidence supports the idea that Caribs arrived in St. Vincent from the Guianas about 1200AD, displacing the Arawaks,21 who are presumed to have been responsible for the enigmatic rock carvings still visible on the island, and that they lived there in large numbers.22

The Caribs said that they had killed the original Arawak inhabitants of the islands.23 Not all the Arawaks, though. The men were put to death but the women were spared and taken as slaves or wives or both. Male Arawak prisoners, it was said, would be elaborately tortured and the Caribs greatly admired the captive who could endure this stoically, although this practice appeared to be dying out even at the time it was recorded.

The Caribs’ style of conquest left its mark on their language. Father Raymond Breton, who compiled the first Carib dictionary, found that the men and women spoke a completely different language “and among them it would be ridiculous to employ the men’s language in speaking to women and vice versa.” The women, it is believed, retained the language of the Arawaks, while the men spoke a version of the language they brought from the mainland, perhaps modified into a pidgin to be understood throughout the islands.24 Just a few vestiges of these differences between men’s and women’s speech are preserved in the Garifuna language today. Linguists, incidentally, classify the Island Carib tongue and modern Garifuna, its direct descendant, as belonging to the Arawak rather than the Carib language group, perhaps indicating that through the womenfolk the Arawak tongue prevailed.25

On St. Vincent a new element would be pitched into this demographic mix.

Like Robinson Crusoe’s Caribbean adventure, the story of the Black Caribs of St. Vincent begins with a shipwreck. At some point a European ship carrying enslaved Africans foundered in the area of St. Vincent and the Grenadines and some or all of its human cargo made it to shore and were taken in by the native inhabitants. Various versions of this tale have been recorded but the details of what actually happened are very hard to pin down.

Looking back from 1789 the British governor of the island, James Seton, said the ship was wrecked “on the windward part of the island of St. Vincent, in the year 1734.”26 An earlier governor...