![]()

Chapter One

John Work II and the Resurrection of the Negro Spiritual in Nashville

The world needs to know that love is stronger than hatred.

—John Wesley Work II

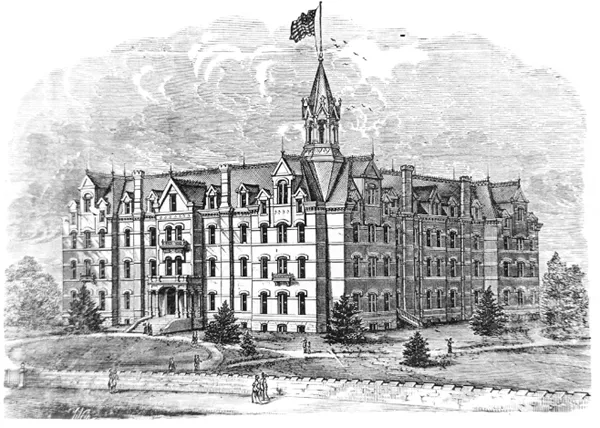

The treasury of African American folk song known as the spirituals arose anonymously from slave cabins and brush arbors and was initially perpetuated as an oral tradition. The Original Fisk Jubilee Singers of Nashville, Tennessee, were first to demonstrate the usefulness of the spirituals, the “genuine jewels we brought from our bondage,” after Emancipation.1 Their singing tours of 1871 to 1875 provided the funds necessary to sustain Fisk University and to build Jubilee Hall, the first permanent structure erected in the South for the purpose of black higher education. These events established a foundational relationship between spiritual singing and black education.

Great spiritual singing is characterized by fervent emotive energy subjected to exacting artistic control. Legend has it that George L. White, director of the Original Fisk Jubilee Singers, “used to tell the singers to put into the tone the intensity that they would give to the most forcible one that they could sing, and yet to make it as soft as they possibly could. ‘If a tiger should step behind you, you would not hear the fall of his foot, yet all the strength of the tiger should be in that tread’ was one of his illustrations of this idea.”2 Evenly blended harmonization is another essential quality—each part distinctly expressed, but with no single voice predominating. As celebrated Fisk Jubilee Singer Frederick Loudin explained, “The object aimed at is to make the voices blend into one grand whole—one beautiful volume.”3 By adhering to these disciplines, striking harmonic effects were achieved, along with sensitive interpretations of the underlying sacred and cultural messages of the spirituals.

Jubilee Hall, Fisk University. (courtesy Franklin Library Special Collections, Fisk University)

By the end of the nineteenth century, male quartets were beginning to replace mixed-voice choruses as the most popular medium for public performance of Negro Spirituals. The jubilee or spiritual quartet phenomenon predates the advent of gospel quartet singing by at least two decades; but in spite of significant stylistic differences, spiritual quartets and gospel quartets represent overlapping, inextricably linked movements in the evolution of African American religious vocal harmony. The methods and principles of spiritual quartet singing directly informed and prepared the way for the emergence of gospel quartets. An abiding respect for music training and education survived the transition. The vigorous application of the formal disciplines of harmony singing at the grassroots level established a design for self-improvement, reinvigorating vernacular quartet singing in much the same way as the perfection of barbershop methodology had done a generation earlier.

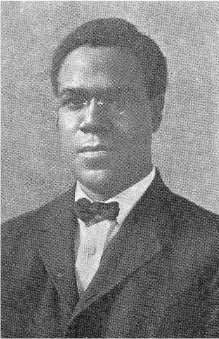

John Work II: Fisk University’s “Hero of Music”

John Wesley Work II was an effective agent of the transition from spiritual to gospel quartet singing. For twenty-five formative years, spiritual singing at Fisk University was Work’s special province. He organized and sang tenor for the illustrious Fisk Jubilee Quartet. He also collected and published Negro folk songs and trained numerous student choirs and glee clubs. Moreover, he exerted extraordinary influence as song leader at the daily exercises in Fisk Chapel, inspiring a new pride in the racial heritage of spiritual singing among the student body.

John Wesley Work II was born in Nashville on August 6, 1873, to John and Samuella Work.4 His father, John Work I was born in slavery in 1848, in Kentucky, where he was originally known as Little Johnny Gray; but after being sold to the Work family of Nashville, he adopted the name John Wesley Work.5 As a teenager Work I was sent in service to New Orleans, where he learned to read and write and became fluent in French.6 He reportedly attended rehearsals at the French Opera House, and by “coming there in close contact with theatrical life learned much of harmony, [and] developed a beautiful voice.”7

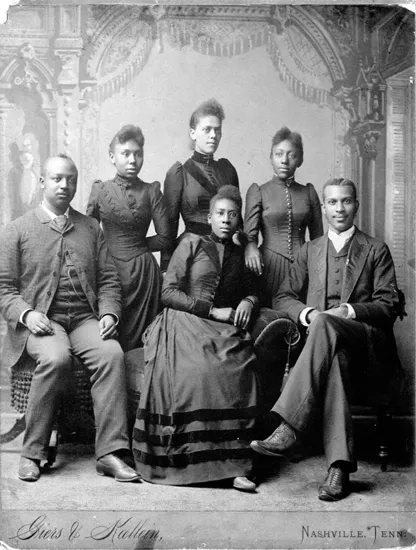

John Wesley Work II. (courtesy Franklin Library Special Collections, Fisk University)

In 1870, Work I returned to Nashville and married Samuella Boyd.8 He taught Sunday school at a mission of the white First Baptist Church, which eventually became an independent African American church. Granddaughter Helen Work maintained that Work I organized the first choir at this historic church, and that three of its members—Maggie Porter, Georgia Gordon, and Minnie Tate—later sang with the Original Fisk Jubilee Singers.9

John Work II was a quartet singer from his early boyhood days until shortly before his death in 1925. His grammar school teacher and lifelong friend Minnie Lou Crosthwaite testified:

As a boy he entered the public schools of Nashville at the time the Board of Education was trying the experiment of placing colored teachers in the colored schools, and Dr. R. S. White, now the honored principal of Knowles School, first laid his hands on John Wesley Work in the educational world. There were two other teachers in this school—now known as Dr. and Mrs. S. W. Crosthwaite. In turn, both of them taught the boy. All of us were afterward transferred to Belleview School, and it was there I became certain of the possibilities that lay in his voice. We had a juvenile quartet consisting of John Work, Alex Rogers, Charles Pugsley, and Alfred Winston. Hundreds of parents and children enjoyed their youthful singing, and later, our friend John delighted the patrons and pupils of Meigs High School with the voice that had steadily grown in power and sweetness of tone.10

Work’s youth quartet illuminates black Nashville’s outsized contribution to turn-of-the-century American popular entertainment. Charles Pugsley and his brother Richmond later organized the Tennessee Warblers, a pioneering company of itinerant singers, musicians, and entertainers.11 Alex Rogers achieved show-business fame as a lyricist for Bert Williams and George Walker’s great musical comedies.12

Work’s long participation in the quartet tradition conferred a deep understanding of the joy of harmonizing that was fixed in black southern culture. He recognized that innovations in recreational quartet singing, particularly improvisational “close chord” constructions—barbershop harmony—were “in keeping with the idea of development” of the spirituals, and not a corrupting influence or a passing phenomenon.13

Work graduated valedictorian from Meigs High School. In the fall of 1891 he entered Fisk University and became wholly absorbed in its activities and traditions. He served as captain of the varsity baseball team, associate editor of the Fisk Herald, and a standout member of every choral club on campus. At graduation he was named “class poet.”14 He later composed the Fisk University anthem “The Gold and Blue,” which is still sung with enthusiasm in Fisk Chapel today.

The Fisk Jubilee Club, ca. 1893. Ella Sheppard Moore and Georgia Gordon Taylor are seated at the far left on the front row. John Work is in the middle row, third from right. Agnes Haynes is in the back row, center. (courtesy Franklin Library Special Collections, Fisk University)

Before Work arrived on campus, Fisk’s most prominent musical organization was the Mozart Society. The University had severed its connections with the Original Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1878, and the spirituals played no great part in the day-to-day life of the students. A significant portion of educated black society viewed the spirituals as an embarrassing vestige of slavery. Abuse of the sacred folk repertoire by minstrel companies of both races had aggravated this feeling. Work reflected:

That Fisk University can truthfully be said in large part to be a product of these plantation melodies is nothing against the fact that just after emancipation the Negro refused to sing his own music in public, especially in the schools …

This is due to the fact that these students have the idea (which is often correct) that white people are looking for amusement in their singing. Some Negroes enjoy being laughed at, but they are not found in the schools. The same students assume the attitude that the rest of the world concedes to the Negroes the ability to execute well their own music, but it is beyond them to understand and execute the classics, and any attempt to do this is presumptuous. To them, this is another form of circumscription which has been a hindrance and handicap.15

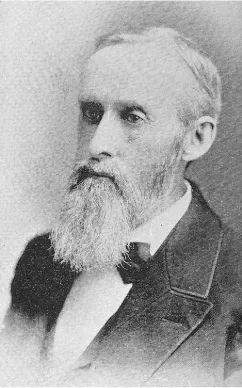

Throughout the 1880s, Fisk’s white principal Adam K. Spence steadfastly led a jubilee song at the daily chapel exercises, undeterred when the students “would ‘join in’ with a chorus of cold silence.”16 Spence was “often obliged to argue with and sometimes scold and drive, or perhaps plead with the young people before the singing would be such as he thought it ought to be.”17 Work expressed with characteristic humility that Spence “from the very first saw the real worth of these songs. He resurrected them for the religious worship in Fisk University, and it was he alone who taught the later generation of students to love and respect them.”18 Work succeeded Spence in leading the daily chapel exercises, and it was Work who ultimately managed to inspire the student body and change the way the spirituals were sung at Fisk.

Adam K. Spence, Fisk University News, October 1911. (courtesy Franklin Library Special Collections, Fisk University)

The first hint of a revival of jubilee singing at Fisk was signaled in 1886, when alumnus Rev. George W. Moore, pastor of Lincoln Memorial Church in Washington, D.C., and husband of Original Fisk Jubilee Singer Ella Sheppard Moore, wrote an open letter to the Fisk Herald, calling for the resurrection of an itinerant company of jubilee singers: “The question has repeatedly presented itself: Why cannot Fisk University again utilize this power of Song, which has such a tenacious hold on the hearts of the people, to sing up an endowment fund as the walls of Jubilee Hall went up? It has young talent in the school and the Mozart Society that could be consecrated to cross this Jordan.”19

The Fisk Jubilee Singers of 1890–91. Basso Thomas W. Talley is on the extreme right. (courtesy Franklin Library Special Collections, Fisk University)

“Jubilee Day,” commemorating the “going out” of the Original Fisk Jubilee Singers on October 6, 1871, has been an official holiday at Fisk since 1874. The Jubilee Day celebration of 1890 “was marked as one of exceptional interest because the music was furnished by the new Jubilee Singers and because of the presence of Mrs. Ella Shepard [sic] Moore”: “The demand for the formation of a new troupe of Jubilee Singers arises from the decision of the officers of the American Missionary Association of New York, to lay the foundation of a new theological seminary … which should have as its object the training of young men for the colored Congregational churches. Rev. Chas. Shelton, Indian Secretary for the A. M. A., has been appointed financial agent for Fisk University and … will leave with the troupe, Oct. 16.”20

The new troupe of Fisk Jubilee Singers was comprised of students drawn, as Rev. Moore had recommended, from the Mozart Society. Ella Sheppard Moore was director; Thomas W. Talley, bass; J. W. Holloway and P. L. La Cour, tenors; Lincolnia Haynes, soprano; Alice Vassar, alto; Fannie E. Snow and Antoinette Crump.21 They made their debut at Birmingham, Connecticut, and then traveled to North Hampton, Massachusetts, to attend the annual meeting of the American Missionary Association. Later, in New York City they sang “Let Your Light Shine All Over the World” for the Sunday school of Broadway Tabernacle and lifted a collection of $500. That same evening they made an appearance at Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn: “When we went into the audience room a multitude of 4000 I think awaited us. The house was packed to the uttermost.”22

On May 27, 1891, the new Jubilee Singers entered the Fisk University dining hall “after an eight month tour of the north. They have visited the principal cities a...