![]()

Chapter One

LICENSE TO TOON

As strange as it may seem, the development of merchandise based on well-known cartoon and comic strip characters was not some sort of gradual evolution. No, indeed; cartoon merchandise has existed as long as there have been cartoon characters, and that came about in 1895.

Of course, the tradition of caricature and political cartooning goes as far back as the American Revolution. However, none of these efforts had produced what we would consider today to be a true cartoon character. That had to wait until an artist named Richard F. Outcault, working for the New York World, instituted a pictorial feature he called Hogan’s Alley. This was not a comic strip but a series of full-page drawings depicting the chaotic goings-on in the titular low-rent-district alley. Almost hidden in the crowd of figures in the first drawing was a bald-headed kid in a dirty nightshirt; no, it was not Charlie Brown, but a personality who came to be known as the Yellow Kid.

Although the Yellow Kid did have vaguely Asian facial features, his ethnicity was not the source of his name. Instead, that appellation came about because the editor of the World, Joseph Pulitzer (no prize for guessing what makes his name live on today), was keen on improving the quality of color printing in the newspaper. For one reason or another, yellow had always been a particularly difficult hue to replicate on the early color printing presses, and when one of Pulitzer’s staff developed what he hoped would be a suitable yellow ink, he randomly chose the nightshirt of the then-anonymous chrome-domed brat in one of Outcault’s drawings as the test area. Overnight, the peculiar tyke became the Yellow Kid—but that was not all.

Outcault was a pioneer not only of American newspaper comics but also in realizing the commercial value of their characters. Within a year, the Yellow Kid was appearing on games, puzzles, dolls, toys, and books reprinting the cartoons—all of which would become the standard for future cartoon stars, right down to the first half of the twenty-first century.

The success of Outcault and his Yellow Kid prompted Pulitzer’s fiercest rival, William Randolph Hearst, to hire Outcault away to draw the feature for his own paper, the New York Journal. Pulitzer retaliated by hiring George Luks to continue the Yellow Kid cartoons in the World, and for a while, the feature continued in two different newspapers under the two different artists. (This sort of cutthroat competition in the newsprint business gave rise to the term “yellow journalism.”) For the next several years, it was not uncommon for the same strip to be drawn by varying artists for separate newspapers until the sticky legal morass of who owned the rights to what could be sorted out.

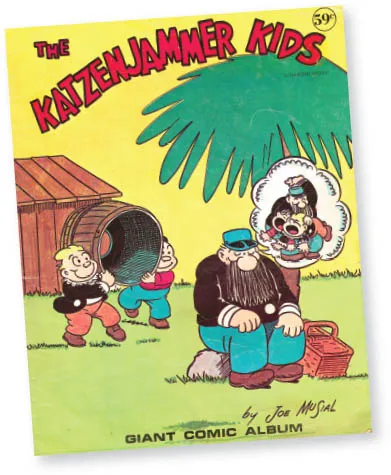

The Katzenjammer Kids is the oldest comic strip still in publication. Merchandise based on the characters was introduced in the late 1890s and was still available when this coloring book was issued in the 1970s.

Another huge step for big-footed cartoon characters came in 1897, when Rudolph Dirks began The Katzenjammer Kids, which would eventually become the first comic strip to reach the hundred-year mark. As a matter of fact, the adventures of the rambunctious Katzenjammer family became the first true comic strip of all, using a series of panels and speech balloons to tell its stories. In a situation quite similar to what happened with the two Yellow Kids, an ownership dispute eventually resulted in two long-running strips with the exact same cast of characters, the original Katzenjammers and their other manifestation, The Captain and the Kids. The two versions coexisted well into the 1970s, although the Katzenjammers proved to be the surviving feature. In 2014, artist Hy Eisman was still producing new Katzenjammer Sunday strips.

While plenty of Katzenjammer toys were in stores, Outcault led the charge when it came to licensed merchandise. The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis was remarkable for being the birthplace of several later pop culture icons, not the least of which was the ice cream cone. Besides exhibiting the world’s largest cast-iron statue and providing the inspiration for the later classic movie Meet Me in St. Louis, the fair was also where Richard Outcault proved once and for all that when he set his mind to license his cartoon creations, he was serious about it.

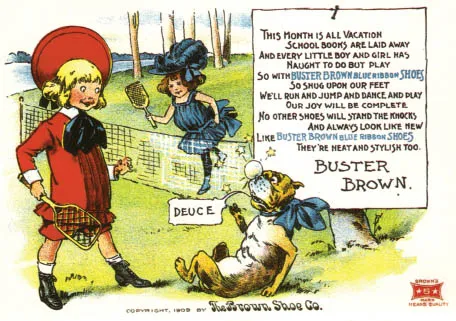

By that time, Outcault had given up on the Yellow Kid and had come up with a much more versatile comic star, Buster Brown. Buster dressed like Little Lord Fauntleroy but had a mean streak that more closely resembled Dennis the Menace; his grinning, toothy dog, Tige, was usually alongside to mumble sarcastic comments on the action, not unlike a later comic strip hound named Snoopy. At the World’s Fair, Outcault set up a booth for the express purpose of licensing Buster Brown merchandise to anyone who had the ready cash to pay for the rights. Many manufacturers took Outcault up on his offer, and stores soon were overrun with Buster Brown toys, books, games, dolls, and all the other usual suspects. However, the two that proved to have the most sticking power were the Brown Shoe Company (which, remarkably, already bore that name before securing the right to make Buster Brown Shoes) and the Buster Brown Textile Company. Both survived long enough to become standard memories for post–World War II baby boomers: Buster Brown Shoes in particular became a childhood icon with their signage of Buster and toothsome Tige and the accompanying slogan: “I’m Buster Brown! I live in a shoe! That’s my dog Tige! He lives in there too!” These advertising images and their related merchandise lasted for decades after their foundational comic strip had ended.

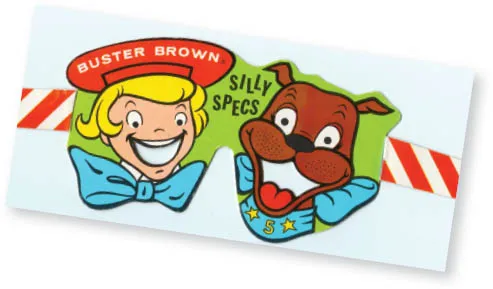

Buster Brown Shoes kept Outcault’s creation before the public long after the comic strip—and Outcault himself—had been forgotten. These wacky cardboard children’s spectacles were only one of the hundreds of different promotional items issued over the years.

At the 1904 World’s Fair, cartoonist Richard Outcault set up a booth to sell licensing rights to his popular comic strip character, Buster Brown. The most famous company to sign one of those deals was Buster Brown Shoes.

During the rest of the 1910s and early 1920s, comic strips remained the biggest source of characters for licensed merchandise. Such titles as Happy Hooligan, The Toonerville Trolley, Moon Mullins, Smitty, and Bringing Up Father (with that original dysfunctional married couple, Maggie and Jiggs) may now be familiar only to cartoon historians, but in their time they all produced shelves full of toys that youngsters of that era craved for Christmas, birthdays, or no special occasion at all.

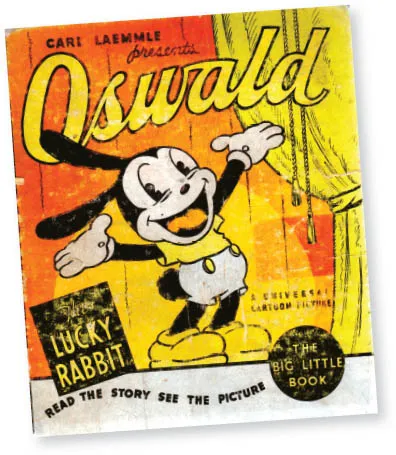

Oswald the Rabbit was created by Walt Disney but legally owned by Universal Pictures. In 1928, control of Oswald was wrested from Disney and eventually passed to Walter Lantz.

There was a very good reason more toys were based on newspaper characters than on animated cartoons, and it was that most of the early animated cartoons were adaptations of newspaper strips. Only occasionally was the print-to-screen cycle broken, with such early animated originals as Walter Lantz’s Dinky Doodle, Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat, and Paul Terry’s Farmer Al Falfa. In the mid-1920s, a young filmmaker from Kansas City journeyed west to try to make a name for himself in the still-primitive cartoon industry. He was Walt Disney, and his cartoon creation would become an early success in licensed merchandise based on an animated character. No, it was not the character you are likely thinking about: it was Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.

Disney produced only twenty-six cartoons featuring Oswald for release by Universal Pictures, but during that relatively short span, the happy hare became popular enough to inspire a few toys and other tie-in items. Disney knew when he had a good thing, and in 1928 he made a trip to New York to ask for more money to produce each Oswald cartoon. Instead, he was informed that he did not own any rights to Oswald and that Universal would be assigning the character to another producer. On the long train ride back to California, Walt did some serious thinking about a character to replace the departed Oswald, and he came up with Mortimer Mouse. Once back in Hollywood, Walt’s wife wisely persuaded him that Mickey sounded friendlier, and Walt set about to make sure moviegoers knew exactly who Mickey Mouse was and who was responsible for his films. Never again would Walt or any of his successors at the company he founded lose control of any of their characters or films, and that control extended into merchandising.

(Incidentally, you may wonder whatever became of Oswald after he was so unceremoniously yanked out from under Disney. Never fear; we will run into him more often than you might think in the chapters that follow.)

Walt Disney had little time to grieve over the loss of Oswald because he was determined to plow every cent he got for each Mickey Mouse short back into the studio, constantly pushing his staff to improve the animation and gags with every film. This also meant that money was usually a bit scarce, and while on another New York visit in the autumn of 1929, Walt made an unplanned deal that was to have far-reaching implications. A man approached Walt in a hotel lobby and offered him three hundred dollars for the right to put Mickey’s picture on the front of a school writing tablet. Since Walt could really use three hundred dollars at the moment, he closed the deal, and the school tablet became the first-ever piece of Disney merchandise. As if you needed to be told, it would hardly be the last one.

This lobby encounter must have reminded Walt of the success he had viewed from afar when Universal was promoting Oswald merchandise, because in December 1929, he and brother/business partner Roy set up an official character licensing and merchandising department as a part of their still-new studio. As Disney historians Robert Heide and John Gilman write, “Disney realized that the future of the studio could become secure only if enough revenue was generated by the character merchandising division.” This would prove to be true for virtually every animation studio in the future, well into the television era and beyond.

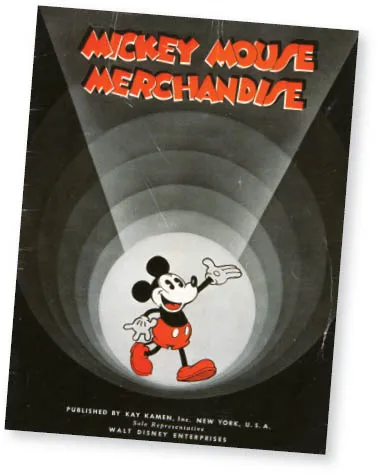

Thanks to promotional genius Kay Kamen, licensed Mickey Mouse and other Disney character merchandise became a major economic force during the Great Depression years. (Hake’s Americana and Collectibles collection)

During 1930 and 1931, some of the earliest (and now most valuable) Mickey Mouse merchandise made its way into stores, but the true genius of that division of the Walt Disney Studios was Kay Kamen, who came to work there in 1932. Kamen was no stranger to licensing, having previously handled the Our Gang kids who appeared in Hal Roach’s comedy shorts. Kamen’s salesmanship soon pushed the already-spinning Disney merchandising machine into hyperaction, just as the Great Depression was tightening its grasp on the public’s collective throat (not to mention its wallet). Most Disney histories give at least a nod to the success of the merchandise of this period, and two companies in particular—Lionel electric trains and the Ingersoll-Waterbury Clock Company—attribute their comeback from impending bankruptcy to the introduction of their Mickey Mouse products. Lionel made a toy handcar for use with its train sets that depicted Mickey and Minnie pumping furiously, while Ingersoll came up with the now-iconic Mickey Mouse watch.

Kamen established a New York licensing office, and there was also a branch on Disney’s home turf in California. According to Heide and Gilman,

The release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in late 1937 set a new precedent for Disney merchandise. Books, toys, and other related items would be on store shelves well in advance of a movie’s premiere, helping build anticipation and familiarity with the characters.

After Donald Duck made his screen debut in 1934, he joined the already-crowded field of characters featured on Disney merchandise.

Design and artwork was supplie...