![]()

Chapter 1

WHAT WE HAD TO OVERCOME

The colored people are good subjects for action pictures; they are natural born humorists and will often assume ridiculous attitudes or say side-splitting things with no apparent intention of being funny. . . . The cartoonist usually plays on the colored man’s love of loud clothes, watermelons, chicken, crap shooting, fear of ghosts, & etc.

—From How to Draw Funny Pictures (1928),

a cartoonist’s instruction manual by E. C. Matthews

As the technology of image reproduction evolved from the late nineteenth century into the twentieth, art prints and lithographs became available to everyday individuals. With photography then still not quite as accessible as it is today, hand-drawn illustrations remained the medium of choice. It was during the publishing boom of the late nineteenth century that the image of African Americans became a marketing tool to sell everything from soap flakes to sheet music to pancake mix. Prior to the Civil War, marketing images of African Americans were not as distorted as they became, with many appearing in sanitized, even carefree depictions of a romanticized antebellum plantation life. But these images degenerated into the sort of offensive caricatures that laid the groundwork for American society’s most enduring negative stereotypes. The nationwide popularity of images of the comically dancing, indolent, watermelon-eating, and crap-shooting, ignorant, dull-witted, “darky” encouraged print makers Currier & Ives and imitators to cash in on the craze. Naturally, craftsmen of the era created more art to satisfy the demand. Borrowing from the already-popular image of the blackface minstrel, the grotesque, hopelessly buffoonish misrepresentation of people of African descent was over time further stylized until it lost all remnants of individuality and humanity.

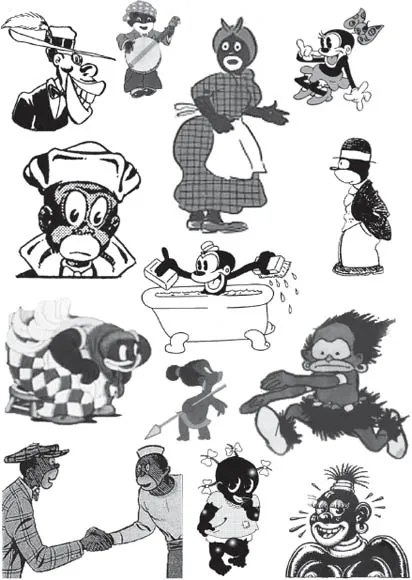

The blackface caricature proliferated in all forms of visual communication, not just comic strips and comic books, but also product packaging, sheet music, decorative flourishes, and so on. It was applied not only to represent contemporary African Americans but to the indigenous or native people of any land. Illustration by Tim Jackson.

This image was fueled by the glossy blackface makeup used in the minstrel show, or minstrelsy, an American entertainment consisting of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music, performed by white people in blackface or, especially after the Civil War, black people in blackface. Minstrel shows were the most popular form of entertainment in America in the mid-1800s. By 1900, it had declined greatly in popularity, giving way to vaudeville. Amateur minstrel shows died in the 1960s with the Civil Right Movement. Elements of minstrelsy, though, lingered well into the 1960s in comics and on television into the 1970s and beyond.

The image of a solidly black visage, drawn from minstrelsy, remained more or less the standard for comical figures in the black-and-white world of newspaper comic strips and even in the early monochrome animated shorts. It is recognizable by the opaque black faces with two large round white circles wherein a black dot or a smaller black circle could roll around. The limbs, too, were opaque and black. Even if little or no other clothing was worn, the hands were likely to be covered with white gloves (before color) and excessively large shoes at the end of short, spindly legs. A perfect example of such a character is Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid, created by early Disney animators Hugh Harman (1903–1982) and Rudolf Ising (1903–1992).

Afterward, Harman and Ising went to work for film producer Leon Schlesinger (1884–1949). Schlesinger went on to develop the Looney Tunes cartoons for the Warner Brothers Studios’ new animation department, introducing the black stereotype there. Minstrel-like imagery can be seen in many nonblack characters of the time, whether they were vague, nonspecific humanoids or singing and dancing animals.

Elements of the minstrel show survive even in recent history. Witness the influence of minstrel-style music in the themes of television programs with all-Black casts. The theme from Sanford and Son is an example, as well as that of What’s Happening?, both shows from the 1970s. Still more curiously, Black television programs even today often begin with everybody dancing.

As evident in the early years of syndicated newspaper comics strips by Whites that bothered to include Black characters at all, there is a heavy dependence upon diminutive, one-is-the-same-as-another Black stereotypes to play the role of low-intelligence but happily subservient domestics, porters, valets, and sidekicks to provide all-around buffoonish comic relief. Hogan’s Alley, also known by the name one of its characters, called The Yellow Kid because of his yellow shirt, was created by young Richard Felton Outcault (1863–1928) and was widely credited as America’s first newspaper comic. It included a pair of grinning, darkly tinted creatures among the usual gang of children. Although all the children were street urchins, the dark creatures were never quite on equal terms with the others. Little Nemo of Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905–1913) was often squired throughout his adventures in Slumberland by the fright-wig coiffed Impie (or the Imp), who dressed in a bizarre grass skirt. Barney Google had his faithful Black jockey, Sunshine, to selflessly worry over his well-being. In Joe and Asbestos (1924–1926, 1931–1966), a horse-race gambler, Joe Quince, had a servile Black companion, Asbestos, the wisecracking stable boy. Even Will Eisner, the much-honored cartoonist and creator of the cult favorite, The Spirit, featured in that cartoon the ungainly Ebony, the shoeshine boy and taxi driver. Then there are the assorted nameless domestics, who served little purpose other than as comical contrasts to the middle-class White main characters in America’s comic pages.

Evidently, not even comic book superheroes were willing to lend their awesome powers to protect African Americans from abuse. In a 1940s issue of Fawcett Publication’s Captain Marvel, “The World’s Mightiest Mortal” in the human guise of Billy Batson, smears his face with burnt cork, the traditional material used in minstrel blackface makeup, saying, “If Mr. Smith asks me who I am, I’ll tell him I’m Rastus Washington Brown from Alabama.” In 1942, in a misguided attempt to appeal to a Black audience, writer Bill Parker (?–?) and cartoonist C. C. Beck (1910–1989) added the Black character Steamboat to the Captain Marvel cast. Steamboat loses his livelihood because of Captain Marvel, and to make amends, he is offered a job as personal servant to young Batson.

Apparently, the editorial staff at Fawcett was oblivious to the fact that Steamboat, with his thick lips, kinky hair, and outrageous dialect was offensive to African American readers. They thought that since he was simply a cartoon character, he should be taken no more seriously than any of the other exaggerated-looking characters in Captain Marvel comics. In 1945, executive editor Will Lieberson finally gave the order to quietly remove the character, agreeing that to some people Steamboat could be viewed as racially insensitive.

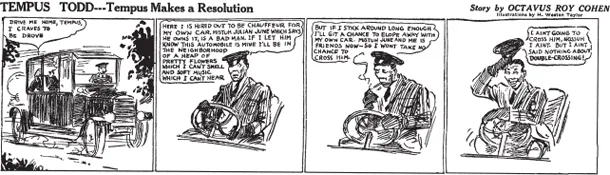

Tempus Todd was a 1923 comic strip written by Octavus Roy Cohen, contributor to the Saturday Evening Post, specializing in tales of black folk that did not use derogatory stereotype images of African Americans. The characters, however, spoke in dialect. H. Weston Taylor was credited as the artist.

A May 5, 1945, Pittsburgh Courier article documents the encounter between Lieberman and a delegation of young people:

Steamboat

Youngsters Protest Ousts Stereotype from Comic Strip

New York — (ANP) Oldsters in their fight against racial prejudice might gain something from representatives of Youthbuilders Inc., who last week persuaded Fawcett publications to drop the character, “Steamboat,” from one of their favorite comic books, “Captain Marvel.”

Pictured as an ape-like creature with coarse Negroid features, including a Southern drawl, Steamboat usurped a great portion of the comic book as [the] villain of the story. The strip was fine, the youngsters all agreed, but such a character will go far to break down all the anti-bias groups are trying to establish. The crusade began at Junior High School 120, Manhattan.

Born Diplomats

Taking up the matter at a meeting of the local chapter of Youthbuilders Inc., a committee was appointed to call on William Lieberson, executive editor of comic books, Fawcett publications, who characterized the group as “born diplomats.”

The kids had a snappy comeback for everything, he said. They pointed out that “Steamboat” was a Negro stereotype tending to magnify race prejudice, and when Lieberson told them that white characters too were depicted in all sorts of ways for the sake of humor, the Youthbuilders retorted that white characters were both heroes and villains while Steamboat, a buffoon, was the only Negro in the strip.

Lieberson was completely won over when one boy produced an enlarged portrait of Steamboat and said, “This is not the Negro race, but your one-and-a-half million readers will think it so.”3

One possible exception to the chronically buffoonish Black image was a strip called Tempus Todd. According to comic art historian Ron Goulart (1933– ), Tempus Todd appeared in syndication in 1923. The strip was drawn by famed Saturday Evening Post illustrator H. Weston Taylor (1881–1978) and was scripted by southern humorist Octavus Roy Cohen (1891–1959), both White. Cohen achieved fame as a writer of humorous fiction about “Negroes,” sporting such titles as Highly Colored (1921), Dark Days (1923), and Black Knights (1923). These comics with their all-Black casts were exceptions in the days of the vacuous minstrel ink blots in that the characters were drawn as individuals with distinct appearances. However, they perpetuated the use of traditional vaudevillian dialect concocted to represent the way all Black people spoke in the world of popular entertainment, no matter where the men or women came from, including Africa.

Some of the Black artists who filled the demand created by the emergence of newspaper comics in the Black press compliantly imitated the same sort of dialect. An example is in Wilbert Holloway’s Sonny Boy Sam (1928). Amazingly, this comic—along with Henry & Mandy and Little Mose/Little Elmo, both drawn by Horace Randolph (?–?)—appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier as late as 1931 at the same time the Courier led the charge to have Amos `n Andy banned from the radio airways because of its “reckless assaults upon the self-respect of a helpless people.” Surprisingly, the blackface characters in these comics appeared seven years later than the more humanistic images in the 1922 comic Amos Hokum, by Jim Watson (?–?), and the 1923 comic Sambo Sims, by Charles W. Russell (?–?), on comic pages of the same newspaper. The characters in other comic strips, such as the 1928 comic Hamm & Beans, by Gus Standard (?–?), spoke in a dialect-free English. Sometimes the dialog featured rhythmical slang phrasing that verged on poetic verse. These are examples of pre-1930 comic strips that were able to successfully present a humorous look into African American life without the negative visual props of the mainstream comics.

Nonetheless, the mainstream cartoon syndicates that supplied newspapers with comics perpetuated derogatory Black images on American comic pages. The legendary African American illustrator, E. Simms Campbell, worked on several comic strips for King Features Syndicate. One was titled Cuties, which featured a variety of pinup girl–style illustrations. The other comic strip he produced for the same cartoon syndicate was titled Hoiman (Herman), which featured a Black porter as the central character. In contrast to the people in Cuties, the Hoiman character was drawn as a nonhuman, drooping lip, solid ink manservant who clumsily attended to the needs of wealthy-looking, non-Black patrons.

As mentioned earlier, this sort of image persisted in America on the comic pages and in comic books into the late 1960s. Outrageous images were to be expected in these genres. Still, Robert Crumb’s 1968 Zap Comics was a particularly egregious example, with multiple appearances of a character called Angelfood McSpade. Angelfood was drawn solidly black, with the stereotypically thick white lips, dressed in a grass skirt, perpetually bare breasted and sexually abused. Crumb’s justification for this racially and well as sexually demeaning character was that she was merely the product of the American culture in which he grew up.

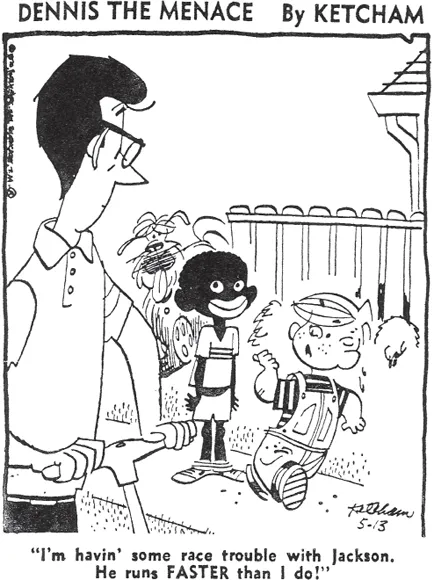

As late as 1970, this unfortunate image was considered acceptable by a nationally beloved cartoonist, and it also passed through a series of editors who found the image acceptable to appear in newspapers nationwide. Illustration by Hank Ketcham.

Apparently, images of these sorts were so deeply imbedded in American culture that they even found their way into a comic strip as innocuous as Dennis the Menace as late as May 1970. According to his autobiography, Merchant of Dennis the Menace (1990), Hank Ketcham viewed himself as being progressive in featuring a Black child, Jackson, in his comic and described the child as “cute as a button.” But Jackson was drawn in blackface style.

I recall my encounter with this comic strip long, long ago. I must have been around twelve, seated in my father’s chair at the head of the dining room table with the morning newspaper, the Dayton Journal Herald, spread out before me as I enjoyed my favorite passion of reading the comics page. Of course, being single-panel comics, Ziggy, Dennis the Menace, and Family Circus were always the attention grabbers of the funny page. Only on that morning this stark, offensive image by Ketcham assaulted me right off. It was as if I had been looking out of the window and seen a beloved companion planting a burning cross on the front lawn. This panel not only mocked me with its the devastating image; I also felt as if it addressed me personally because the wide-eyed blackface affront named Jackson even called me by name! In unrestrained rage, I spat on the comic, ripped it out of the newspaper along with whatever cartoons surrounded it, wadded the page into as tight a ball I was able to crush it, and threw it onto the kitchen stove, lit the gas, and watched it burn and curl into an ash. Yet this act did not assuage the pain I felt (and sometimes still feel). Smelling the smoke, my mother asked me why I did it. All I could tell her was a pensive “I don’t know.” It was a deep disappointment that defied words.

As early as the 1920s, Black cartoonists were taking emphatic control of their self-image. An example is Bungleton Green, the eponymous character of a comic who starts out as a vagrant but evolves into a leading citizen. Bungleton Green was a gag comic—a multi-panel strip that sets up a situation which ends with a punchline or sight gag—begun by Leslie Rogers (1896–1935) that was similar in artistic style to Bud Fisher’s Mutt & Jeff and had a long run from 1920 to 1964. In keeping with The Great Gatsby–inspired Jazz Age era of philosophical “flapper” features (in which party girls dispense nurturing advice), a social satire by Jay Paul Jackson (1905–1954), As Others See Us, appearing in 1928, offered a similar slice-of-life glimpse of society from an Afrocentric perspective, minus the minstrel caricatures of African Americans—except when he used the minstrel image to make a point about people exhibiting unacceptable behavior within the African American community. In the beginning of the comic strip Sunny Boy Sam in 1928, all of the characters used dialect. By the 1930s, dialect was no longer emplo...