![]()

1

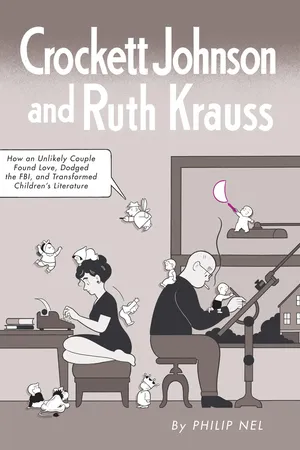

RUTH KRAUSS’S CHARMED CHILDHOOD

There should be a parade when a baby is born.

—RUTH KRAUSS, Open House for Butterflies (1960)

During a midnight storm on 25 July 1901, Ruth Ida Krauss was born. She emerged with a full head of long black hair and her thumb in her mouth. According to Ruth’s birth certificate, twenty-one-year-old Blanche Krauss gave birth at 1025 North Calvert Street, a Baltimore address that did not exist. This future writer of fiction was born in a fictional place. Or so her birth certificate alleges. But it was filed in 1933, at which time the attending physician did live at the above address. Presumably, she was born at 1012 McCulloh, which in 1901 was the doctor’s address and a little over a mile from the Krauss home. Her father, twenty-eight-year-old Julius Leopold Krauss, was in the unusual position of being able to afford to have a doctor attend to his child’s birth—at the turn of the twentieth century, 95 percent of children were born at home, and physicians were present at only 50 percent of births.1

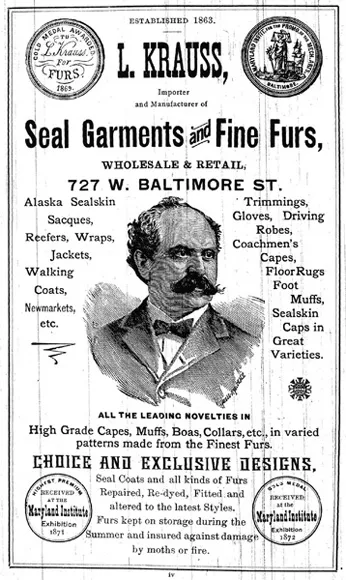

Ruth came home to the three-story frame house at 2137 Linden Avenue, where she lived with her doting mother, father, and paternal grandfather, Leopold Krauss, who had been born in Budapest, Hungary, about 1839. His wife, Elsie, had been born in Frankfurt in about 1848. After the failed European revolutions of 1848 and the German wars of unification in the 1860s, Leopold joined the great wave of U.S.-bound immigrants, and by 1863, he had settled in downtown Baltimore, where he operated a furrier’s business. In 1869 and 1872, his furs won gold medals from the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts.2

Elsie emigrated to the United States at around the same time and soon met and married Leopold Krauss. They and their two children, Carrie (born 1871) and Julius (born 1872), lived a comfortably middle-class life. Both children attended school, Elsie kept house, and Leopold ran a thriving business in a rising clothing industry center. Although Ruth recalled that Julius “liked to draw & paint,” he followed his father into the furrier’s trade. By 1893, he was working for Leopold as a salesman, and five years later, Julius had become manager. In 1899, the business changed its name from “Leopold Krauss” to “L. Krauss & Son,” but within two years, Leopold Krauss dropped “& Son,” and in 1902, Julius Krauss opened his own furrier shop, though he returned to his father’s firm a year later and remained there for the rest of his working life. He may have had to cede his creative ambitions to his father, but his daughter would be able to pursue her dreams. Julius would see to that.3

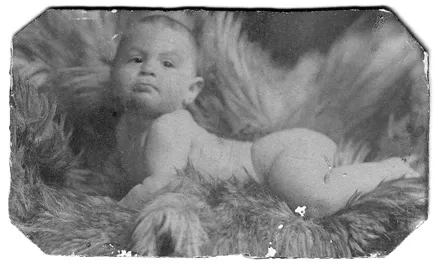

Ruth Krauss at six months. Image courtesy of Betty Hahn.

Just before the turn of the twentieth century, Julius Krauss met Blanche Rosenfeld. Born in about 1879 in St. Louis, Blanche had moved to Baltimore as a child. She, too, was the daughter of an immigrant—Australian-born Carrie Mayer—and her husband, Henry Rosenfeld.4

On Sunday, 14 October 1900, Blanche and Julius married at Baltimore’s beautiful new Eutaw Place Temple. The young couple soon moved with Ruth’s father and grandfather into the Linden Avenue house. (Grandmother Elsie died before she could meet her daughter-in-law.) Like many other affluent Baltimore Jews, the Krausses migrated northwest through the city into the neighborhoods just south of Druid Hill Park. Although the Krauss family moved frequently during Ruth’s childhood, they never resided more than half a dozen blocks south the park. Established in 1860, Druid Hill was part of the same urban parks movement that inspired Central Park. By the turn of the twentieth century, it was Baltimore’s largest park, with fountains, a duck pond, gardens, stables, a greenhouse, a zoo, tennis courts, swimming pools, and a lake for summer boating and winter ice skating. Because Baltimore was a segregated city, the park also had separate facilities for use by black visitors, an injustice that left an impression on young Ruth. An active child, Ruth made frequent use of the park—when she was well.5

Advertisement from Baltimore City Directory, 1893: Leopold Krauss, Ruth’s grandfather.

As an infant, Ruth developed a severe earache, and doctors discovered that her ear was infected and filled with fluid. She underwent an operation to drain the ear and had to wear a bandage around her head for the next year. Ruth also suffered from many childhood diseases that were common in the days before vaccinations, including diphtheria, two kinds of measles, chicken pox, and whooping cough. She later recalled, “I nearly died a lot.” Nevertheless, she recovered and grew into an energetic and inquisitive little girl. At three years old, she stood in her house’s bay window and lifted her dress so that two passing women could see her. At five, she and two boys played show and tell behind a couch.6

Ruth Krauss, ca. 1916. Image courtesy of Betty Hahn.

Ruth’s parents catered to their only child’s needs. When she grew old enough to go to school, she cried so much that her family relented and let her stay home. The following year, when she began attending school, she returned home each day to find a piece of chocolate on her dresser, a reward from her grandfather.7

Ruth’s earliest ambition was to be an acrobat. She later recalled having spent “eight years of my life walking on my hands in the backyard.” There were many different backyards. In 1903, the Krausses moved a block and a half north to a three-story frame house at 826 Newington Avenue. In 1904, they moved three blocks south, to another three-story frame house at 1904 Linden Avenue. In February 1904, the Great Baltimore Fire destroyed more than fifteen hundred buildings in the city’s downtown business district, but the Druid Hill Park neighborhood and the Krausses’ shop at 228–230 North Eutaw Street were far enough north that they escaped the flames. Memories of the conflagration stayed with Ruth, who had a lifelong fear of house fires.8

By 1907, the family had moved yet again, this time taking their servant and cook five blocks northwest to a brand-new, stone-front, three-story house at 2529 Madison Avenue, where they would remain for the next eight years. According to Gilbert Sandler, Jews in the area, known as the Eutaw Place–Lake neighborhood, “founded their own separate society, with an in-town club (the Phoenix Club), a country club (the Suburban Club), and their own funeral home (the Sondheim Funeral Home).”9

Health problems continued to plague Ruth. At age eleven, she developed appendicitis and had an appendectomy. The next year, she came down with pemphigus, a rare autoimmune disorder that results in blistering of the skin and mucous membranes. Despite the efforts of five excellent doctors, including a skin specialist from Johns Hopkins, she spent two months in bed, becoming so weak that she could no longer speak and could ask for a glass of water only by wiggling the little finger on her left hand. To lift the girl’s spirits, Blanche Krauss and her three sisters took turns reading to her—all of H. Irving Hancock’s Dick Prescott stories. As Ruth recalled, “They took Dick from the time he was a little squirt and finished him off at Westpoint [sic] when he got engaged. I can remember my Aunt Edna giggling as she read to me how Dick got himself engaged.” Only later, after her recovery, did Ruth learn that pemphigus was usually fatal: Doctors told her that only one other person had survived, and he “had to live in a bathtub of ice for a year”—or at least that was her “impression of the story.”10

While she was convalescing, Ruth received a bicycle from her family. Not yet permitted to leave the house, she learned to ride in the hallway so that “the first time I was able to go outside after being sick, I could ride it.”11

Ruth remained close to her grandfather, Leopold, who would read her the Twenty-Third Psalm (“The Lord is my shepherd”) and letters his wife had written him when they were engaged, an experience she found “very touching.” As the fall of 1913 turned to winter, Leopold’s health declined, and one day Ruth returned from school to find her dresser without its usual piece of chocolate. On 8 December 1913, Leopold Krauss died at the age of seventy-six.12

Ruth found some consolation in stories. She enjoyed listening when her father told her about his childhood and read to her from David Copperfield. On her own, she read fairy stories and reread the Dick Prescott stories. She also began writing and illustrating her own stories. When she finished a story, she created a binding by sewing the pages together along one edge. As a teenager, she wrote in a secret language a book that she hid from her parents.13

In 1915, Ruth enrolled at Baltimore’s Western Female High School, and the family moved to the Marlborough, a new luxury apartment building at the corner of Eutaw Place and Wilson Street whose other residents included several prominent Baltimoreans, notably Claribel and Etta Cone, major patrons of Impressionist and post-Impressionist art. The Cone sisters’ eighth-floor apartment became a private museum, featuring works by Picasso, Matisse, and Renoir. If the building’s double-thick fireproof walls and concrete floors truly did ensure “absolute immunity from noisy neighbors,” as management claimed, the Krausses’ neighbors were probably grateful. During her teenage years, Ruth took up the violin. She was a creative if not technically accomplished player. Holding the violin between her chin and neck gave her a chronic boil, so she began practicing with the far end of the violin against a wall, delighted by the different sounds that resulted: “A plaster wall gave one sound. Wall-board another, quite sepulchral. A wooden door gave another. The bathroom tile, still another.” Ruth imagined herself performing on a concert stage, running around and pressing the violin against different objects to get different sounds.14

Ruth studied violin with the Peabody Conservatory’s Franz C. Bornschein, a teacher, composer, and arranger who was also giving lessons at Western Female High School. Unlike some girls’ schools of the time, Western was no mere finishing school. Ruth attended twice-weekly physical education classes and studied both science (botany or physiology for freshmen and zoology or biology for sophomores) and foreign languages (Latin, French, German, or Spanish).15

In 1917, after her sophomore year, Ruth left Western to become an artist. She later noted that because her “formal education stopped after two years of public high school,” she was “naturally illiterate in my language and I sometimes wonder if this isn’t simply a continuation of the way I talked as a child.” Ruth enrolled as a day student in the new costume design program at the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts (now the Maryland Institute College of Art). Ruth’s interest in exploring her creativity collided with the school’s pragmatic emphasis on subjects such as interior decoration, which would, according to the institute’s director, Charles Y. Turner, “offer a medium of making the young artist self-supporting in a far shorter space of time than the painting of abstract subjects or portrait work.” In addition to making inexpensive goods for domestic consumption, graduates also made clothes and other items for American troops abroad.16

Free of the need to earn a wage, Ruth did not participate in war industries. By 1918, she and her parents had moved to the Rochester, another upscale apartment building, located just over a mile from the Maryland Institute. Most of Ruth’s costume design classmates were female, in keeping with prevailing views about pursuits for which women were suited. In the words of costume design instructor Elsie R. Brown, “Mother Eve herself ranked clothes only second in her scheme of things, curiosity about apples being her first and consuming interest.” Similarly, an article on the costume design program noted that “women naturally have an instinctive interest in clothes.” But Ruth’s interests were pulling her away from costume design, and in mid-1919, she left the Maryland Institute and began thinking about resuming her study of the violin.17

First, however, she went to Camp Walden, deep in the woods of Denmark, Maine. Her five weeks there were transformative. Though her family had moved six times in eighteen years, she had always lived in the same neighborhood. Far away from Baltimore for the first time, Ruth rediscovered writing.18

![]()

2

BECOMING CROCKETT JOHNSON

“Have you been doing any thinking about what you’re going to be when you grow up?” asked Ellen.

“No,” said the lion. “Have you?”

—CROCKETT JOHNSON, Ellen’s Lion (1959)

Crockett Johnson was born David Johnson Leisk (pronounced Lisk), in New York City, on 20 October 1906. His grandfather, David Leask, was a carpenter in Lerwick, in Scotland’s Shetland Islands. He and his wife, Jane, ultimately had ten children, all of whom attended school until they were old enough to learn a trade. Their third child and second son, named for his father, was born on 3 August 1865, and by age fifteen, he was an apprentice stationer. By 1890, after a brief career as a journalist, young David had left what he called the “treeless isles” and emigrated to New York, where he found work as a bookkeeper at the Johnson Lumber Compa...