one

THE MAN FROM HIROSHIMA

It was a man from Hiroshima with a Buddha-like smile who introduced me to haiku in Japan. Thinking back, there was little else that distinguished him. He was about sixty-five years old, bald, and of middling height. He wore a polo shirt, polyester pants, and loafers—much like a golfer, which he later told me he was.

I had just finished giving a presentation on the topic of Northeast Asia to a group of about twenty elderly Bunkyo University alumni and their friends gathered in a midsize hotel in downtown Tokyo. As an American diplomat in Japan, I spent many evenings talking to informal groups like this one about world events and especially about North Korea, whose worrisome missiles and nuclear ambitions were front-page news in Japan.

It was late, and I was tired. I sensed my audience did not care what I said; they were of a generation where a foreigner speaking Japanese was enough to grab their attention.

Still, the evening was far from over. Nearly every occasion in Japan requires a brief aisatsu, a mixture of a toast and self-introduction, and I knew tonight would be no different. I had not thought about what I would say. Giving a speech in Japanese was hard enough. Although I had lived in Japan for nearly eight years spread over two decades and had spent a good ten years learning the language, I had still devoted the better part of a month preparing for this speech. I wrote a draft in English and had it translated, then asked a Japanese colleague to read it into a tape recorder. I carried the tape around with me for days, earphones on, tape recorder running, mumbling aloud as I pushed my way through the crowded streets of Tokyo. The previous Saturday afternoon I practiced the speech while sitting on the sidelines of my nine-year-old son Sam’s soccer practice, mouthing the phrases, pausing the tape now and again to look a word up in the dictionary. At one point, Sam came over to tell me his team was switching fields and that I had to move. Later, his foot appeared on the ground in front of me. I looked up at him as from a fog. Mom, tie my shoe, he instructed gently. I stopped the tape and tied his shoe, wondering as I did so whether my failure to run up and down the field cheering him on would make him a less confident adult. I finished tying his shoe and kissed his chubby leg. He ran back onto the field, and my uncertainty evaporated in the crisp fall air as the distance between us grew.

People were getting up from their chairs, and heading out. I followed them into the room next door, where there were several buffet tables, seats along the back wall, and a standing microphone in the center. I took a seat and looked at my watch. It was 9:30 P.M. By now our three children would be in bed and my husband would be quietly reading. I had missed another evening with my family. What was I doing in this hotel among strangers? Someone was at the microphone. It was hard to tune into his Japanese mid-course. I listened to his voice without hearing the words, a waterfall of sounds splashing in no predictable direction.

We were on the tenth floor of the hotel. My thoughts drifted. What would happen if an earthquake hit right at that moment? I thought I might be feeling some tremors. Earthquakes are common in Japan. At home we had moved all the bookcases away from the beds and we kept a half-dozen gallon jugs of water under the kitchen sink in case the water supply became contaminated. I tried to size up the strength of the beams facing me. If there were an earthquake right now, would it be better for me to hug the vertical beams or run to the door frame? Everyone in Japan is told to run to the door frame; I would use my wits and go for the beam. People would be shrieking and shouting. Sirens would be going off. A woman would grab her purse and then drop it when she realized her survival was all that mattered. I imagined myself crouching behind the beam, protected from flying shards of glass. I would spring into action—cool, levelheaded, reassuring people and directing them to safety. If it was a really big earthquake, I would call the State Department Operations Center in Washington from my cell phone: the first to report it, our woman in Tokyo.

The bald man in the polo shirt came to sit in the empty seat next to me, and I floated back to reality, mechanically reaching for my business cards. As a professional woman in Japan, I had learned to get my meishi, or business cards, across early, not just because women are often underestimated in Japan, but because of an important corollary: rank trumps gender. Once they saw I was a diplomat, I came to life for my interlocutors.

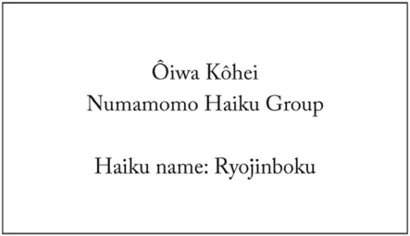

I kept my meishi in a neat leather holder; his were jammed in his billfold. He spent a few moments searching through his wallet, slowly pulling out and replacing a few until he found the one with his own name on it:

This was a very odd Japanese calling card. Mr. Ōiwa had no company affiliation. What was the Numamomo Haiku Group? Did Mr. Ōiwa work there? And if so, what was his position? I knew a little about haiku, those unrhymed Japanese poems capturing the essence of a moment, usually seventeen syllables in Japanese. I liked reading haiku at night before going to bed. They were short and quick to read, and I was a busy person. I liked being able to read a beautiful haiku for relaxation while at the same time improving my Japanese-language skills.

The man also seemed to have two names. Should I refer to him as Mr. Ōiwa or as Mr. Ryojinboku? I was not sure what Ryojinboku meant, although I could see that the three characters—旅、人、木—individually stood for Traveling Man Tree. I pictured Mr. Ōiwa as a man-tree with a kind smile and warm eyes, with leafy branches delicately growing from his head as he walked, dragging roots at his feet and stopping occasionally to rest and compose haiku.

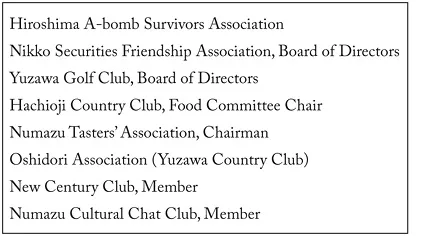

On the reverse side of his business card, Traveling Man Tree had carefully listed his interests and affiliations:

Hiroshima A-bomb Survivors Association. My husband and I had lived in Hiroshima for nearly two years shortly after we were married. It was our first experience living in Japan. My husband, an English teacher, had grown up in a Navy family reading books on World War II, watching samurai movies, and dreaming of Japan. When he was offered a job in Hiroshima, it was a chance for him to see with his own eyes a place that for years had lived in his imagination. As for me, Japan held no special meaning, but neither did my job as a lawyer in Washington, D.C. Within a month of his job offer, I closed my fledgling solo practice, said goodbye to family and friends, and left with him for the land of the rising sun. I was one month pregnant.

Eight months later I was in labor on the third floor of Dr. Takahara’s Lady Clinic, desperately trying to convey in broken Japanese, May I now have the honorable injection please? (The injection never came and this is when I first learned the importance of speaking the language of the country where I live.)

I looked at Traveling Man Tree’s card again. I could have met Traveling Man Tree at the time I was living in Hiroshima, without even realizing it, but back then he would have been just another faceless, middle-aged businessman to me. My Japanese was so poor that it would have been impossible for me to strike up a conversation with a stranger anyway. It was only some months after settling in Hiroshima that I began studying Japanese. My husband and I were living in a tiny Japanese-style apartment. Each day as he left for work, I would hear the frosted-glass sliding door rattle shut and wonder how I was going to find a job in a country where I did not speak the language, where my American law degree meant noth...