This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This illustrated study of Tenryuji, ranked number one among the five great Zen temples of Kyoto and a major destination for tourism and worship, weaves together history, design, culture, and personal reflection to reveal the inner workings of a great spiritual institution. Looking at Tenryuji's present as a mirror to its past, and detailing the famous pond and rockwork composition by renowned designer Muso Soseki, Norris Brock Johnson presents the first full-length "biography" of a Zen temple garden.

Norris Brock Johnson is a professor of anthropology at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and has been teaching and writing about Japanese temple gardens for over twenty years.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Tenryu-ji by Norris Brock Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biowissenschaften & Gartenbau. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

BiowissenschaftenSubtopic

Gartenbau| I | Land, Landscape, and the Spirit of Place |

Even after decades,

if someone digs in the ruins …

human bones’ll

still come out,

won’t they?

YŌKO ŌTA

“Residues of Squalor”1

I

MOUNTAINS, WATER, AND FRAGRANT TREES

Prior to the seventh century, it had been the custom to abandon the court of an emperor or empress after their death, as each site was then considered polluted. New sites, purified places, were prepared for each successive emperor or empress. Imperial courts grew in size, and relocations increasingly became cumbersome; in time, imperial coursts became semipermanent, then permanent.

In 710, during the reign of Empress Genmyō (Genmei, 660–721), Nara (Heijō-kyō, Capital of the Peaceful Citadel) became an influential capital city for imperial courts. Rather than defer to concerns over death and pollution, selection of the site for the Capital of the Peaceful Citadel in large part was based on then-favorable aspects of the surrounding area, in particular, the sensory delights afforded to people of privilege through aesthetic experiences of the Yamato Plain.

Nara (Level Land), though, increasingly became subject to periodic flooding as the imperial city had been sited near the Saho and Tomio rivers. Aesthetic enjoyment of the area around Nara did not offset the growing belief that the land itself was failing to influence the well-being of emperors, the city, and its people.

Virtue and the Breath of Life

Changing conceptions of and attitudes toward the land and landscape around Nara influenced temporary relocation of the imperial capital, in 784, to Nagaoka. In 794, Emperor Kanmu (737–806) ordered the imperial capital moved from Nara to a new site that became known as the Capital of Peace and Tranquillity (Kyōto).

The land on which Kyōto was sited had been donated to Emperor Kanmu by the Hata family, wealthy descendants of immigrants from Korea. Kyōto was believed to be free of the malevolent influences causing undesirable environmental changes within areas in and around Nara. At this time, nature (自然, shizen) was believed to embody animistic qualities demonstrably affecting people—land and human-created landscapes were auspicious, or not, and favorably influenced well-being, or not. People of influence felt that the site and topography of Nara were not balancing wind and water, but increasingly favored water. They believed that the area north of Nara better balanced wind and water.1

Principles and practices for enhancing aspects of nature deemed beneficent were known as Storing Wind/Acquiring Water (蔵風得水, zōfū tokushi), which coexisted with imported Chinese feng shui principles and practices of Wind/Water.2

Feng shui animistically conceived of the earth as an organic body laced with arterial veins through which the Breath of Life (qi; 気, ki in Japan) flowed. The Breath of Life flowed and circulated more intensely in some spaces and places more than in others. Well-being was enhanced through detecting intensive flows of the Breath of Life embodied as distinctive features of the land itself, then through fashioning habitats congruent with the flow of the Breath of Life. By the ninth century, the rudiments of feng shui were present in Japan; indeed, “the senior Ministry of State, the Nakatsukasa, included a special department, the Onmyō-Ryō (陰陽寮, Bureau of Yin-Yang), with a select staff of masters and doctors of divination and astrology.”3 The Chinese Southern Sung Dynasty (1127–1279) was a period of comparatively intense exchange between China and Japan, and “it was not until the rise of the Sung Dynasty that all the elements of feng shui gathered into one system.”4 During the later Southern Sung Dynasty, Buddhist priests from China studied in Japan and Buddhist priests from Japan studied in China. The Ajari, for instance, were Japanese Buddhist specialists in Chinese yin yang (陰陽, in yō in Japan).

Congruent with Chinese feng shui, Japanese zōfū tokushi emphasized the conjoining of aspects of nature and specific directions. South was considered a beneficent direction while north was the least propitious direction. East was associated with dragons and water while west was associated with tigers and mountains. In an ideal site for human habitation, enhancing well-being, “mountains come from behind, which is to say from the north, and end at this point [the site selected], overlooked a plain ahead. On the left and right, mountain ranges extend southward to protect the area; they are known as the ‘undulations of the green dragon’ and the ‘deferential bowing of the white tiger.’ To the south are spreading flatlands or low hills. As a rule, water from the mountains flows down through the area bounded by them. In short, there are mountains behind and a plain with flowing water in front. Such a location is suitable for zōfū tokushi conditions.”5 Selection of the site on which Kyōto was constructed acknowledged the influence of nature on the well-being of people, in particular the influence of a favorable balancing of mountains and water.

Favorably open toward the south, Kyōto was laid out on a plain between auspicious aspects of nature to the north, east, and west.6With protecting hills and mountains to the north, east, and west, Kyōto was sited within a beneficent space between tiger (west) and the dragon (east) mountains.

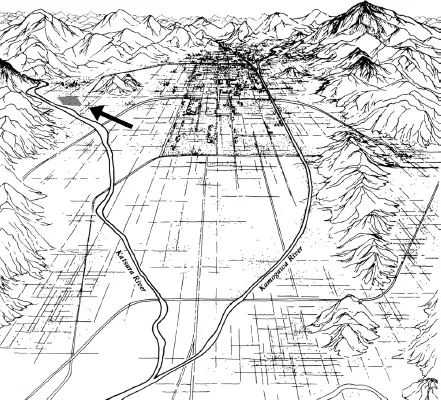

Kyōto was sited with respect to the Katsura River and the Kamo River, both of which flowed auspiciously toward the south into low-lying basins fed by numerous springs flowing down from surrounding mountains. Interestingly, “the mountains surrounding the City of Purple Mountains and Crystal Streams [Kyōto] were considered ‘male [in],’ and … along the foot of the eastern hills flowed the Kamo River, which curved around at the south, again as topographical tradition demanded; the Katsura River to the west of the city provided the second of the two essential ‘female [yō]’ elements.”7 Kyōto was auspiciously sited within a low-lying basin surrounded on three sides by mountains with the fourth side, the south side, open to the flowing waters of rivers, a siting believed to enhance the well-being of the city and its inhabitants (figs. 2, 30).

FIGURE 30. The city of Kyōto was sited within a basin surrounded, and balanced, by (tiger) mountains to the west and (dragon) mountains to the east. Tenryū-ji (toward where the arrow is pointing), a dragon presence, subsequently was sited within, and balanced by, the tiger-mountains to the west of the city.

Kyōto also was known as the City of Purple Hills and Crystal Streams (山紫水明, Sanshi Suimei, Place of Great Natural Beauty). This poetic name signified the manner in which the new imperial capital interwove the city proper with aspects of nature, in particular mountains and water. “The capital [Kyōto] itself was situated in beautiful country, encircled on three sides by thickly forested hills and mountains, often delicately wreathed with trails of mist; in the autumn evenings one could hear the deer’s cry in the distance, and the desolate call of the wild geese overhead; the landscape abounded in streams and waterfalls and lakes; and into its green slopes and valleys the countless shrines and monasteries blended as if they too had become a part of nature.”8 Here, a human-created landscape was experienced as an intimate aspect of nature, similar to a forthcoming chapter’s narratives on people’s early experiences of the landscape of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon as nature.9 In the section “Revealing the Nature of Buddha-Nature,” for instance, we will see that in the fourteeenth century the landscape of the temple included features such as a Dragon-Gate Pavilion, the fabled Moon-Crossing Bridge, and a shrine evocatively renamed Buddha’s Light of the World—architectured features placed in nature some distance from the central areas of the temple.

Wind circulates the Breath of Life. Water embraces the Breath of Life. “The ch’i, the cosmic breaths which constitute the virtue of a site, are blown about by the wind and held by the waters.”10 A circulating balance of wind and water was believed not only to be auspicious, beneficent, but to be virtuous as well.

The Temple of the Heavenly Dragon, much later, will be sited within a balanced, auspicious confluence of low-lying bodies of water nestled within encircling mountains (fig. 5). Locating the temple amid mountains and water long associated with well-being by contagious contact was believed to enhance the moral character and mission of the complex. The temple was considered a repository of virtue, as we will see, an especially beneficent place for the living as well as for the deceased.

A Most Beautiful Meadow

After the capital had been relocated from Nara to Kyōto, a succession of emperors and aristocrats began to find favor with Sagano (Saga), a lush region within the mountains west of Kyōto, for the location of compounds built as retreats from the city (fig. 2). Sagano was praised as “the best meadow of all, no doubt because of its beauty as a landscape.”11 Ōigawa (the Abundant-Flowing River), merging with the Katsura River, flowed through Sagano. The Mountain of Storms lay to the west/southwest of the river while Turtle Mountain and the plains of Sagano lay to the north/northeast of the river.

Emperors and aristocrats began to designate Sagano a protected reserve for hunting, excursions, and retreats from Kyōto. Emperor Saga, for instance, so loved Sagano that he took his name from that region. His love for the mountains and plains west of Kyōto later will be shared by Go-Daigo (1288–1339), one of his descendants who will participate directly in the genesis of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon.

The Sagano region of western Kyōto became important to practitioners of Shintō as well as to the early presence of Buddhism in Japan. In addition to the pleasure retreats of emperors and the nobility, the human-created landscape in Sagano began to exhibit compounds physically marking the presence of Buddhism and Shintō.

A Palace-in-the-Field

The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari), most likely written from about 1008 through 1021 by Lady Murasaki Shikibu (ca. 973–1025), provides an early glimpse of the region of Sagano. The Tale of Genji contains vivid descriptions of people and events associated with rites of purification critical to the venerated Grand Shrine at Ise (present-day Mie Prefecture, southeast of Kyōto).12

In the Tale of Genji, compounds termed “Palace-in-the-Field” were built in Sagano as secluded settings for princesses, high priestesses, from the family of an emperor. Prior to representing an emperor at Ise, a priestess was required to live for a year within a Palace-in-the-Field while undergoing rites of purification.13 Priestesses were purified in the flowing waters of the Katsura River prior to being escorted to Ise.14 After a priestess had been escorted to Ise, the compound associated with her purification was dismantled. A new compound was constructed each time a priestess was prepared to represent an emperor by living at Ise.

To our eyes, though, the word “palace” misdescribes the compounds built within Sagano. Consider the manner in which the Tale of Genji describes Prince Genji’s approach to a Palace-in-the-Field: “They came at last,” Lady Murasaki writes, “to a group of very temporary wooden huts surrounded by a flimsy brushwood fence. The archways, built of unstripped wood, stood solemnly against the sky. Within the enclosure a number of priests were walking up and down with a preoccupied air.”15 Prince Genji steals into the compound to secret a love note to Lady Rokujō, of the imperial court, whose daughter (Akikonomu) was being prepared to live within the Grand Shrine at Ise. The area described here was set apart, isolated spatially, and was entered through “archways” (鳥居, torii) still signaling spaces and places associated with Shintō.

Prince Genji, we read, then entered an enchanted garden within the Palace-in-the-Field. Having secreted his note to Lady Rokujō, Prince Genji lingers in contemplating how “the garden which surrounded her apartments was laid out in so enchanting a manner that the troops of young courtiers, who in the early days of the retreat had sought in vain to press their attentions upon her, used, even when she had sent them about their business, to linger there regretfully; and on this marvelous night the place seemed consciously to be deploying all its charm.”16 A striking aspect of this garden is its animistic quality and presence. The garden enchants, casts a spell, and the spell of the garden is so compelling as to force the gaze of courtiers ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- The Pond in the Garden

- Part I

- Part II: A Garden in Green Shade

- Part III: Garden as Life and Spirit