![]()

CHAPTER 1

Perception according to Ibn ′Arabi

God in Forms

Before any discussion can take place regarding divine beauty and its expression in amorous poetry, it is necessary to establish the experience of divine beauty. Because the poetry of Ibn ‘Arabi and ‘Iraqi concerns itself with encounters and observations that they refer to as a vision, this segment asks an important preliminary question: What exactly is it that the person accomplished in esoteric knowledge of God, the gnostic (‘arif), perceives? In the end, since this vision must be directly experienced, it escapes the boundaries of language. Not surprisingly, then, it seems that Ibn ‘Arabi’s efforts to articulate and analyze this unspeakable perceptive experience yielded diverse sets of terms.

Each set of terms presents this vision differently, from a certain perspective, and is often described in the language of the Qur’an or prophetic narrations (of course, Ibn ‘Arabi’s use of these terms is also a commentary on their original usage in the revealed sources). An interpreter of Ibn ‘Arabi must acknowledge the varying nuances that these groups of words offer—because the abundance of concepts and terms in the writings of Ibn ‘Arabi is an attempt to achieve some accuracy in articulating that which ultimately must be tasted.

What I offer here is not a complete presentation of perception in the thought of Ibn ‘Arabi, which would be a useful undertaking, but one that would require a separate and lengthy study. After all, shuhud—a term referring to “witnessing” in a general sense, the most basic and definitive perceptive experience of the mystic and that most relevant to our discussion—involves the entire experience of the gnostic, including his or her knowledge of the divine attributes, the divine names, the entifications, and practically anything that the privileged insight of the gnostic can assert. Rather, presented here are certain key points, especially those that relate to the experiential visions related to beauty and love and thus often found in Sufi poetry.

The Importance of Witnessing to Ibn ‘Arabi’s Thought

Traditionally, Ibn ‘Arabi has been classified as the great expositor of Islamic mysticism’s most famous theory of existence—the Oneness of Being, or wahdat al-wujud. A number of Ibn ‘Arabi’s statements point to a lack of any concrete distinction between the Creator and creation, such that everything seen is none other than the Real, and that created entities possess their own separate existence in only an illusory way:

There is no creation seen by the eye,

except that its essence/eye is the Real.

Yet he is hidden therein,

thus, its [creation’s] forms are [his] receptacles.1

Yet William C. Chittick, among others, has rightly taken great pains to illustrate that not only did the phrase wahdat al-wujud (Oneness of Being) emerge and gain currency after Ibn ‘Arabi’s death but also the terms and technicalities of this theory are often not explicitly found in his writings.2

Ibn ‘Arabi was not primarily concerned with forming an ontological philosophy or with arguments and proofs because the greatest proof for him was that which he acquired through direct witnessing. He was, however, concerned (and, one might say, primarily concerned) with vision, and that which he presents in his writings is—first and foremost—a way of perceiving things, witnessing the Real in both the mundane and the lofty, in the “spiritual” as well as the “worldly” and material. For Ibn ‘Arabi, “everyone in existence is Real / and everyone in witnessing is a creation.”3 That is, in terms of existence, the created things lack self-sufficient being, so that all is God. In terms of witnessing, however, creation and creation alone—on account of having nothing, being in a sense ontologically poor—has the ability to receive wujud/existence and engage in shuhud/witnessing.

Creation is receptive and, like an uncluttered mirror, serves as the means for God to witness himself. Throughout this process, creation is both seer and seen, and yet the actual seer and seen are God. Moreover, this “seeing” or “witnessing” is for Ibn ‘Arabi the primary purpose of creation. For Ibn ‘Arabi, the Real created the cosmos in order to see himself.4 In making such a statement, Ibn ‘Arabi alludes to a well-known prophetic narration, one in which God speaks in the first person: “I was a Treasure—I was Unknown, so I loved to be known. Hence I created the creatures, and made Myself known to them, so they knew Me.”5 In other words, the very impetus for all of creation proceeds from the Real’s love to be known, and his love to be known or “witnessed” justifies and maintains creation’s ongoing existence. As Ibn ‘Arabi states, “Were creation not witnessed through the Real, it/he would not be,” and “were the Real not witnessed through creation, you would not be.”6 The phrase “Oneness of Witnessing,” if interpreted according to this understanding, is almost as adequate a description of Ibn ‘Arabi’s system as the phrase “Oneness of Being,” despite the fact that interpreters of Ibn ‘Arabi have placed far less importance on shuhud/witnessing.7

Witnessing: To Know That Which Is Seen

With regard to Ibn ‘Arabi, the numerous perceptive perspectives that will be described broadly fall under the umbrella term shuhud or mushahadah, both translated here as “witnessing.” Judging from Ibn ‘Arabi’s description of mushahadah in chapter 209 of his central work al-Futuhat al-Makkiyah (The Meccan Openings), a chapter devoted to this topic, mushahadah/witnessing is foundational for the gnostic. In fact, witnessing serves as the first requirement or first sign of becoming a gnostic or ‘arif. Before achieving such witnessing, the wayfarer is merely a novice, since only after the wayfarer is “called to witness” do terms such as “place” (makanah) or “station” (maqam) apply to him or her:

When you are called to witness, you are confirmed, my lad!

Then place and station are in order for you.

So you witness him with your intellect in a veiling,

for the place of his witnessing is powerful, unwished for.

You witness him through himself in everything—

“behind” does not apply to him, he has no “in front,”

and you are tranquil in seeing him, so tranquil.

Through him there is ascertainment and peace.8

In this chapter, Ibn ‘Arabi describes mushahadah/witnessing as that important visionary ability to see things as they really are, not as they merely appear to be. Even when reason or the senses dictate that a perceived object must correspond to one thing, the gnostic gifted with witnessing knows that indeed that object is something else.

Ibn ‘Arabi gives two important examples from the scriptural sources of those who lack this ability, those who lack “knowledge of that which is witnessed,” in order to teach through negative example. The Queen of Sheba, named “Bilqis,” exclaims that the throne she sees in Solomon’s court resembles her own throne (“it is as if it is it!” 27:42), unable to see that her very own throne has indeed been instantaneously transported into the court of Solomon. This is on account of the boggling distance that separates her court from Solomon’s court, a distance the instantaneous circumventing of which reason must reject. Second, the companions of the Prophet see the young and handsome Dihyah al-Kalbi as Dihyah al-Kalbi even when the angel of revelation Gabriel takes on the form of the young man. In other words, in one example, a person lacking vision (the Queen of Sheba) cannot see an object of vision as itself, and in another example, a group (the companions of the Prophet) cannot see an object of vision representing something else.9 That which most people see, in other words, corresponds to their sense of reason but does not correspond to reality. The various planes of existence are infused with meaning, communications from God, and symbolic significance—yet only those granted mushahadah/witnessing have awareness of the true states of things.

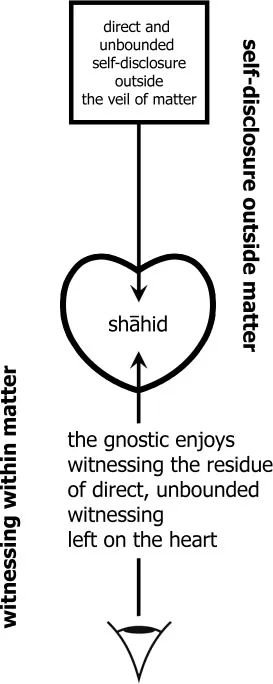

Making Sense of Terms

The use here of two different terms—mushahadah and shuhud—to describe one experience, “witnessing,” should not be offsetting since the two terms can be interchanged in Ibn ‘Arabi’s writings. Sometimes, however, the two terms do maintain distinct definitions and are part of a set of terms that describe more broadly “witnessing,” each with its own subtle difference in meaning. When the two are distinct, mushahadah can refer to a specific grade and type of esoteric knowledge, while shuhud usually refers to the general experience of witnessing as creation’s receptive orientation toward existence and sometimes refers to “presence” or being manifest. A third term, ru’yah (vision), at times refers to a visionary experience more intense than mushahadah, one that is direct in that it makes no use of an intermediary. Distinguishing mushahadah/witnessing from ru’yah/vision, Ibn ‘Arabi defines mushahadah as “the witnessing [shuhud] of the evidential locus [shahid] in the heart from the Real,” which—unlike ru’yah—is “fettered by signs” or, one might say, “signifiers” (quyyida bi-l-’alamah).10 That is, the mystic first encounters the divine in the realm of formless and absolute meaning, where interaction is direct and incomprehensible. This leaves a mark within the heart—a trace or “testimony” or “evidential locus.” The witnessing of that testimony or shahid results in mushahadah.

This description of mushahadah/witnessing parallels the definition of ‘ilm (knowledge) by classic Islamic philosophers as the “presence of a thing’s form in the intellect.”11 Just as (for the philosophers) things and the relationships between them leave traces of their forms in the intellect, so too, according to Ibn ‘Arabi, does that which is witnessed leave a trace of its form in the soul.12 It is thus interesting to note that Ibn ‘Arabi seems to offer witnessing as an esoteric counterpart to the knowledge described by philosophers—a sort of knowing that occurs not in the intellect (al’aql) but in the heart (al-qalb) or soul (al-nafs), since Ibn ‘Arabi alternately recognizes both as the site where the form of the witnessed (al-mashhud) abides.13 Much like the functioning of the intellect, which uses that which is known to understand the unknown,14 the heart uses that which it knows and has witnessed to behold the hitherto unwitnessed, unknown, or unexperienced. Thus this witnessing occurs through preconceptions and is not wholly receptive.

A wholly receptive vision that involves no preconceptions applies only to ru’yah/vision, for “ru’yah is not preceded by knowledge of the seen, while shuhud/witnessing is in fact preceded by knowledge of the witnessed.”15 For this reason, vision (ru’yah) has immediacy and is an unattained goal for many even from among the highest ranks. According to Ibn ‘Arabi, for example, Moses’ expressed wish to “see” God (7:143), establishes that he longs for something beyond mushahadah/witnessing, since according to Ibn ‘Arabi even those below the rank of prophet partake in mushahadah/witnessing. Hence mushahadah/witnessing is a type of ru’yah/vision bound by the knowledge of the viewer, and mushahadah/witnessing is more readily available, at least in preresurrection life, than true ru’yah/vision.

Also, Ibn ‘Arabi tells us that mushahadah/witnessing involves an opening or divine display on a lower level than mukashafah/unveiling. Ibn ‘Arabi defines and contrasts these two terms, mushahadah and mukashafah, in chapters 209 and 210 of al-Futuhat al-Makkiyah, in which he comments on the usage of these terms as part of the developed technical vocabulary of the Sufis.16 While Ibn ‘Arabi’s overall discussion proves very original, his specific, threefold Sufi definitions of mushahadah/witnessing and mukashafah/unveiling closely parallel those from Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali’s (d. 505/1111) section on Sufi terms in Kitab al-Imla’ fi Ishkalat al-Ihya’ (The Book Resolving Uncertainties in the Ihya’), a text written in response to criticisms of his masterpiece Ihya’ ‘Ulum al-Din (The Revival of the Religious Sciences).17 In Kitab al-Imla’, al-Ghazali seems to have wanted to prove his ability to use Sufi terms in what had become part of a technical vocabulary, since he, like Ibn ‘Arabi, does not usually confine himself to such usage in his major writings.

The definitions based on al-Ghazali’s text will not concern us for now. It suffices to know that Ibn ‘Arabi agrees with al-Ghazali that unveiling exceeds witnessing in excellence, despite the fact that some earlier masters held witnessing to be higher than unveiling.18 While witnessing is a pathway to true knowledge, Ibn ‘Arabi contends, unveiling is the full attainment of that pathway to knowledge. While witnessing relies on the physic...