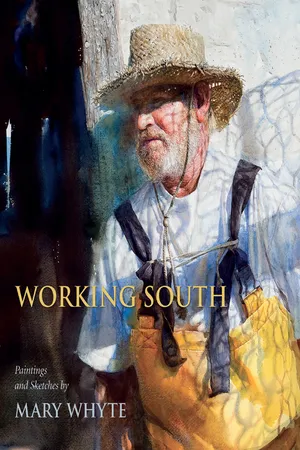

![]()

THE PAINTINGS

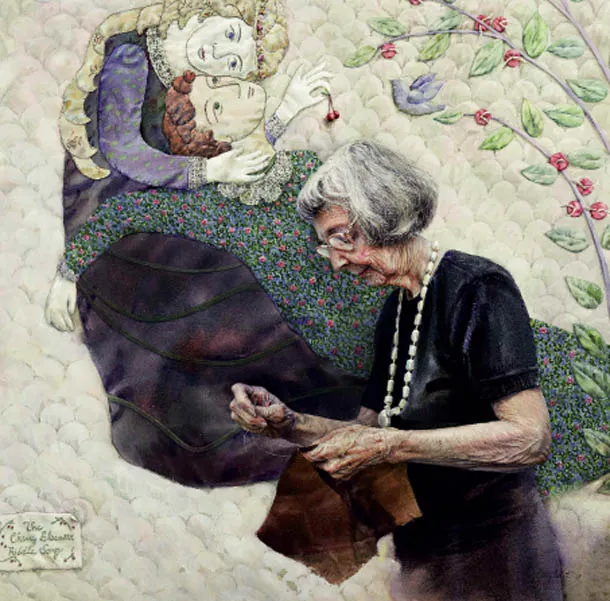

Lovers, detail. Quilter, Berea, Ky.

Spinner. Textile mill worker, Gaffney, S.C. Watercolor on paper, 28½ × 36½ inches, 2007

Fifteen-Minute Break. Industrial equipment cleaners, Bishopville, S.C. Watercolor on paper, 58 × 38¾ inches, 2008

![]()

January 15

Gray Court, South Carolina

There are two hog farms left in Laurens County, South Carolina. Locals swear that the Bobo family’s pork chops are the best in the state. The Bobo farm is spread wide, over a series of soft hills that join together and slope down to a pond ringed by tall trees. A gray sow with beige spots stands shoulder deep in the water, paying little attention to her offspring, who are sleeping in the dry winter grass, or to my car as it slows down at the sign for the country store.

It is a small white cinderblock building. Outside in front are two parked pickup trucks, one with a six-foot steel cage in back. I peek in the rear of the truck and see the only thing in the cage is a straight-back wooden chair on its side. I smile. They are expecting me. I glance again at the chair and notice it is identical to the one I use in my little upstate rented studio not too far from the hog farm. It’s an odd thing for us to have in common.

I enter the store and see a large refrigerated cooler. Through the fogged glass, I can see trays with thick slabs of bacon, a mound of ground sausage, pink chops, and tenderloins. The whole space is immaculate and sparse: a polished floor, a rack of candy and chips, a simple Formica check-out counter by the door. In the back corner, a group of men sit in worn chairs around a glowing heater the size of a microwave. They nod to me.

I walk over and extend my hand to the one with the cane. William Bobo is almost eighty years old and, although I was told he has not been feeling well lately, clearly still keeps tabs on everything in the store. His two sons, John and Ralph, help keep the business going, including the care and feeding of seventy-five hogs and their constantly growing piglets. The men all wear caps and sturdy work clothes. Mr. Bobo is wearing a red-and-black plaid wool jacket and beige cap.

I take an empty seat in the semicircle of men, telling them about my project and asking questions about hogs.

“Are they smart?”

“Oh they smart alright,” says John, tilting back on two metal legs of his chair. “They know when lightning is coming long for we do. They’re low to the ground, so they feel the air turning right up through their feet.” The other men nod in agreement.

Ralph is enormous, six and a half feet tall, and wide. He tells me about how almost everyone in these parts used to have hogs, feeding them big in the summer and then slaughtering them in the cooler winter months.

“Many families had a smokehouse on the property,” he said, and a place to store the salty, cured pork. “Now there are hardly any hog farms left in the South.”

Most hogs are now raised in the Midwest on huge tracts of land that are more like factories. No lolling around in the pond for those pigs.

I ask old Mr. Bobo about his earliest memories of the pig business. He laughs and shakes his head.

“When I was thirteen,” he said, “I swapped two pigs for a bicycle.”

Since then the business has grown considerably. In spite of all their hard work, they have steep competition. The megafarms can produce more and keep the prices lower.

“We’re just trying to raise ’em for the price we’re getting for them,” Bobo says.

“If it wasn’t for the store,” adds Ralph, “we couldn’t make it. It’s all because of the people we have coming in each week to buy.”

I close my sketchbook and ask if we can go out to see the hogs.

Mr. Bobo gets into one truck, and John gets into the other. I follow both pickup trucks a short way down the road. We stop along the side of the road on a sloped, rutted area where years of run-off have washed away anything that had ever hoped to grow. Here the fence curves away along the edge of the road, then disappears behind a knoll. On the other side of the fence are a dozen hogs, mostly sows, all milling about in the warm winter sun. In the distance I can see the sketchy lines of a fence drawn into a lazy square, with small pink ovals beneath the trees.

Holding a bag of feed on his shoulder, John swings open the gate, and we walk into the penned area. The ground feels warm in the winter sun. Tufts of dry grass cling to the churned dirt.

“Watch out for that one,” John says, motioning toward the shed, where I can see the large hulk of a sow sleeping in the shadows. “She’s a mean one.”

A few feet away from her, two small piglets wobble into the sunlight. John tilts the bag and starts pouring the grain into a trough. A cloud of white envelopes him as hogs skirt and swirl around us squealing and scuffling, snouts and rumps colliding in the surge. I’m no farmer, but I’ve been to enough Thanksgiving dinners to know this is all going to be over in a minute, so I get down on one knee and start taking pictures. I am at eye level and only a few feet from the trough, and can hear the grunting and snorting and the sound of grain crunching under heavy weight. The biggest male has his front feet in the trough, and only his ears, which are as big as hands, show over the top of the bin. He roars and spins, snapping at one of the smaller pigs, which sends the rest protesting in a squall of dust. A roiling tempest of pink veers around me as each pig forces its way into the center.

In a flash I picture the absurd headline to my obituary, something surely mentioning “HOG HEAVEN,” a clip that even strangers will cut out and save. Then the storm of swine eases. Hogs start moving away, hovering together about fifteen feet from the trough. One sow backs off from the group and cautiously moves toward me, giving low wheezing snorts, wriggling her nose up to the camera lens until she is an inch away. I stand up, and she jerks back, feet kicking. She eyes me for a few seconds, then loses interest. A few smaller pigs sniff the ground, nudging the trough, checking around the corners. Most of the bigger hogs are wandering off, back to the center of the pen, loosely gathered a few feet from each other. Their feet stand on oval shadows. Soon it is quiet.

I put the lens cap back on the camera. As if coming out of a dream, it takes me a second to remember where I am. John is over by the truck, folding something up and putting it in the back. I turn around. Mr. Bobo is sitting on the wooden chair facing away from me. He is motionless, his papery hands folded on top of his cane, his back barely touching the chair. His large brown shoes sink ankle deep into the grass, and the sun sits in small triangles on his nose and cheeks. He is squinting slightly, staring out over the pond at something way in the distance.

Sentinel. Hog farmer, Gray Court, S.C. Watercolor on paper, 28½ × 34½ inches, 2010

New Year. Milliner, Atlanta, Ga. Watercolor on paper, 22½ × 29 inches, 2009

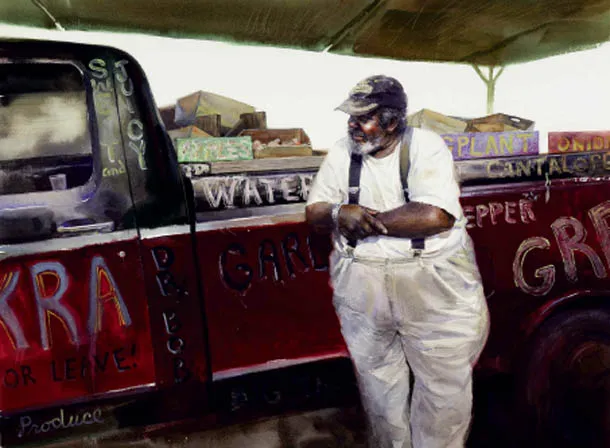

Mr. Okra. Produce vendor, New Orleans, La. Watercolor on paper, 28½ × 38½ inches, 2008

Lovers. Quilter, Berea, Ky. Watercolor on paper, 26½ × 27⅛ inches, 2008

![]()

February 23

New Orleans, Louisiana

The apartment we have rented for the month vibrates, shaking the Mardi Gras beads looped around our second-floor balcony. Cars cruise below, pulsating with loud, deep rhythms that make the leaded glass windows buzz. If I lean over the railing far enough, I can see a river of people on Bourbon Street. Below two men in gray suits tap their oversized plastic wine glasses together and laugh. It is early morning.

I take the stairs to the street and thread my way toward Canal Street, stepping over discarded cups and puddles of frothy, foul-smelling liquid. Vendors wearing Dr. Seuss hats and layers of silver chains hold up souvenirs. Rap music spills out the door of a club. In the window is a large black and white photo of two young women kissing and an advertisement for free food with the cover charge. On Canal Street the street cars grind and clang as I push open the brass revolving door and enter the hotel lobby.

I take the escalator to the second floor, where the plush carpeted hallway is lined with...