![]()

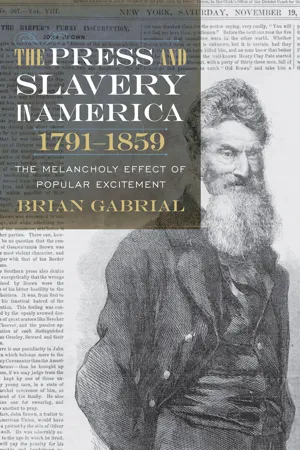

PART I THE PRESS AND SLAVE TROUBLES IN AMERICA

Slavery had become enshrined in American law and culture by 1800. Despite this, many black Americans refused to accept the idea that their lives (or, if free, the lives of their slave brethren) had little meaning beyond the boundaries of their masters’ domains. Among those were people such as Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner, who, along with allies such as John Brown, made fateful choices about helping themselves and other slaves strike out for freedom. In due course they all sealed their fates because they could never overcome powerful forces that supported black American slavery as natural and right. Indeed these conspirators and rebels were committing great crimes against the state, and they would pay for their deeds with their lives.

Part 1 provides a brief look at these events that often stunned white Americans out of a lethargic belief that black Americans did not want nor cherish liberty. It begins with the story of the slave revolt on the island of Santo Domingo because, of all the events, this rebellion elicited a continuing discourse in the newspaper stories about what black violence against white people meant. As these reports with their graphic details about the revolt spread from newspaper to newspaper, they left little doubt about what might happen in slave country if America’s black slaves decided to rebel. In fact a newspaper reader would need little explanation what the “horrors of Santo Domingo” meant. Details from newspapers stories about subsequent revolts and conspiracies that culminated in the events at Harper’s Ferry then provide a clear view of the situation.

Slavery’s proponents also became obsessed with silencing other enemies of slavery who attacked the “peculiar institution” with their words or by their very existence. These enemies included free blacks and abolitionists and their political allies. Slave owners especially feared that “incendiary” words from abolitionist or antislavery factions would also filter down to their slaves and incite them to rebellion. As George Fredrickson asserted in The Black Image in the White Mind: “Southern slave owners were extraordinarily careful to maintain absolute control over their ‘people’ and to quarantine them from any kind of outside influence that might inspire dissatisfaction with their condition” (p. 53). Similarly, Eugene Genovese in Roll, Jordan, Roll observed that the slave power controlled the press in the slave South and worked at suppressing news accounts of slave revolts and conspiracies to impress readers—white or black—that the owners fully controlled their human property (p. 50). One Richmond, Virginia, newspaper editor, following Nat Turner’s revolt in 1831, cautioned southern colleagues against giving slaves “false conceptions of their numbers and capacity by exhibiting the terror and confusion of the whites and to induce them to think it [revolt] practicable” (Stampp, Peculiar Institution, 136).

Still, stories about slave troubles appeared in the nation’s newspapers, and imbedded in them are discourses about slavery. These discourses, discussed later in more detail, are situated within the context that created them. Part 1 shows how newspaper content from 1800 to 1831 about Prosser, Louisiana, Vesey, and Turner expressed similar ideas about slavery as being an unfortunate colonial legacy. The nature of these stories also illustrates the nature of an American press that had yet to undergo the technological transformations that would make news mass and instant. By 1859 those changes in the press became apparent in the reports about John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry. Newspapers had become active news gatherers not mere news collectors. What also emerges with those changes is a sense that the critical alterations in America’s political, social, and geographic landscape that had turned a small, Atlantic coastal nation into a vast, increasingly powerful country that stretched from one ocean to the next was now on the verge of splintering in two.

![]()

1 | | Haiti in 1791, Gabriel Prosser’s 1800 Conspiracy, and the 1811 German Coast Slave Revolt |

At reading the following every heart must shudder with horror.

New York Daily Advertiser, October 1, 1800

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, most Americans learned about the 1791 Haitian slave revolt, Gabriel Prosser’s 1800 conspiracy, and the slave revolt that shook Louisiana in 1811 from newspapers that had changed little since the invention of the printing press. Certainly the way American newspaper editors shared news remained the same, with one newspaper’s content being reprinted in newspapers in other cities. Importantly, these news accounts most often originated as correspondence from the affected areas. Thus the only information a Boston reader would receive about a slave conspiracy or revolt in Virginia came from a slave owner or the authorities there. Such would be the nature of news in the partisan press era.

As this information was shared and repeated within the country’s newspapers, it shaped a way of thinking about slaves, slave rebels, and other black people in America. In other words it formed a discourse. Such discourse concerned the marginalization of slave rebels during the troubles and reflects America’s racist ideology that held blacks inferior, unworthy of freedom despite their struggles in an age when such efforts to obtain liberty should have resonated positively with post–Revolutionary War Americans. In each news account the black rebel is always an immediate threat to the white-controlled slave system and is transformed into an objectified thing that must be stopped and destroyed.

Even as late as 1831 and at the time of Nat Turner’s revolt, the press “was more closely akin to that which existed fifty years earlier, than it was to the press which would exist a mere thirty years later,” according to Henry Irving Tragle.1 Until technological changes such as rotary presses and manufacturing of cheap paper became common, newspapers between 1791 and 1831 looked much the same—usually four- to six-page broadsheets filled with commercial advertisements and a page or possibly two of “news” content and opinion. Their editors, likely serving as both printers and publishers, relied nearly exclusively on other newspapers for content, editorial or otherwise.2

In this partisan press era such content took days, weeks, or even months by ship or horseback to reach other cities and towns. Because these newspapers were relatively expensive to produce, they catered to an elite, literate readership that could pay for them. Often the newspapers were passed along to others and shared within communities.3 Yet distribution could hardly be considered wide, and as such it cannot be determined with any certainty how many Americans read reports of America’s slave troubles or what effect these reports would have had on them. This would be the case for stories about Santo Domingo, Gabriel Prosser, and the German Coast.

Another important facet about newspapers during this period is that rumor and speculation ran rampant in their pages.4 Citing sources was rare, and editors often printed stories to serve their political sensibilities and allegiances.5 In addition objectivity as a professional journalistic standard was decades away from development.6 This meant that nearly all published content during the partisan era of the press contained biases as well as exaggerations. Still, the stories found in these newspapers offer important clues about what happened when slave troubles occurred, and for most readers living far from Santo Domingo, Henrico County, or Louisiana’s German Coast, this would have been the only information they would get.

When serious slave troubles erupted, the news items took the form of firsthand narratives written by (white) eyewitnesses, who sent them as correspondences to their local newspaper editors/publishers. From Massachusetts to Pennsylvania to South Carolina, newspaper editors shared these correspondences with one another.7 On occasion some would send their letters directly to friends, relatives, or newspaper editors located great distances away. Often rich in detail, both exaggerated and real, this information provided insight and perspective on late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century white American views on slavery and their fellow black Americans.8 For white readers, regardless of their sympathies for or against slavery, any slave trouble involving black violence against fellow whites meant disaster. In America the first defining event that shook southern slave society to its core took place on an island just off the nation’s coast, and the letters sent by frantic whites from French-controlled Santo Domingo (Haiti) spelled out clearly what black-on-white violence truly meant.

Haiti’s Slave Revolt

When the Haitian slave revolt began in the summer of 1791, the letters reaching American shores were, as one historian wrote, “received with legitimate terror by the white people of the South.”9 Before 1800 no slave trouble alarmed white Americans more than this rebellion in French-controlled Hispaniola, then referred to as St. Dominique, San Domingo, or Santo Domingo. Years later in news accounts of later slave troubles, the very mention of Haiti in those stories “symbolized how extensive racial disorder might be and served to rally whites to defense of their race and institutions.”10 The whole idea of “Santo Domingo” became a compacted, recurrent intertextual discourse that exploded in newspapers anytime later slave troubles occurred, summarizing immediately for the reader what black-on-white violence meant.

To France, Haiti was the jewel in its colonial crown. To Americans, it was a valuable trading partner, supplying North America with 30 percent of its sugar imports.11 The revolt began in the summer of 1791 when black slaves, enraged that the French National Assembly broke its promise of freedom, rebelled, killing scores of white men, women, and children.12 That fall word about the revolt finally reached newspapers in the United States. “INSURRECTION OF NEGROES,” read a headline in the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser on September 21. Under it was a letter, dated August 26, from a “gentleman at CAPE FRANCOIS” (a major northern port city) who, writing “to his friend in New-York,” explained that “an insurrection broke out amongst the Negroes and Mulattoes, and they are now destroying every Person and thing they come across”; the desolate writer added, “There are now eleven Plantations on fire in sight, and where it will end God only knows.”13 Weeks later another letter, dated September 18, reached New York and Boston newspapers, telling readers that the situation had only deteriorated: “The blacks have continued their ravages; they have burnt and destroyed almost every sugar plantation in this part of the island.”14 The writer lamented, “When these devastations will cease, is as uncertain as it was on the first day of the insurrection.”15 From 1791 to 1804 rebelling slaves in disparate groups fought the French and struggled for control of the island. Eventually strong leaders such as Toussaint L’Ouverture and Jean Dessalines expelled their colonial overseers, leading to Haiti’s independence in 1804 ...