![]()

Chapter 1: Constance Fenimore Woolson and the Tourist Outback of Florida

In another twenty years, I think the war of 1861 will be more a thing of the past than that of 1776; because we shall not want to remember it.

—Constance Fenimore Woolson

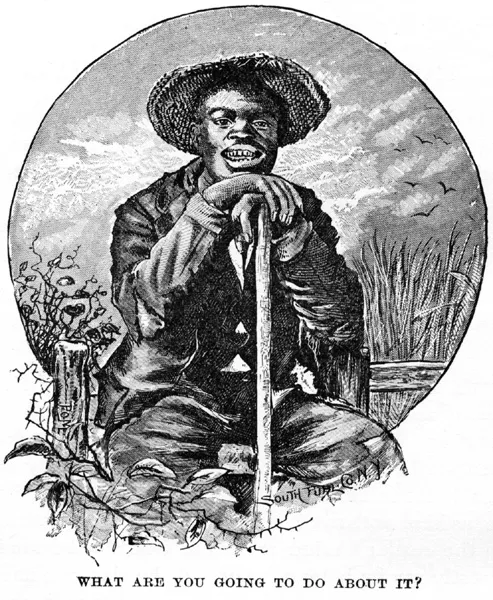

Northern white writer Constance Fenimore Woolson’s travel sketches and stories about Florida, written from 1873 to 1879, showed readers different possibilities for reconstructing the South. A decade earlier, many white southerners worried that freedpeople would not work hard for their former white masters, now employers. This vexing concern, as well as anxiety over freedpeople’s place in American society more generally, permeated the genre of tourist literature, which grew after the Civil War. One such publication was Oliver Martin Crosby’s Florida Facts Both Bright and Blue. The guidebook’s appendix of essays by “Resident Experts” specifically addressed “The Productive Capacity of Florida for the Sustenance of Population, Based upon its Climatic Conditions.” Introducing this appendix was an illustration featuring a sitting freedman with a cane—or is it a hoe?—in hand whose gaze directly confronts the reader. The caption reads, “What Are You Going to Do About It?” (Fig. 3). While making gender central to her vision of Reconstruction, Woolson was one writer who did “something about it.”1

More than any other Reconstruction writer, Woolson imagined freedpeople, particularly freedwomen, as successful citizens in an ethnically diverse country. While others viewed the freedpeople as exclusively a labor force, Woolson saw a cultured community in which women played agential roles in advancing political reform. Despite Woolson’s prediction that the Civil War would be soon forgotten, the issues for which the war was fought certainly were not. Her writing contributed to ongoing debates over the definition of citizenship, the meaning of freedom, and the fate of free-labor ideology. Her magazine articles helped foster the rise of a consumer culture, transforming eastern Florida (part of the Third Military District, which also included Georgia and Alabama) into a tourist paradise for northerners. Woolson is unique, however, because her work both lured readers to Florida and drew their attention to those already established there.

FIGURE 3. “What Are You Going to Do About It?,” Oliver Marvin Crosby, Florida Facts Both Bright and Blue (New York, 1887), n.p.

Woolson achieved this end using three key strategies. First, her travel sketches relocated national origin myths from New England to the ancient cities of Florida, taking advantage of the state’s varied colonial history. Most broadly, her reportage of the Floridian landscape helped piece together a southern identity that attracted northern consumers, thus helping reformulate divided national identities along a gendered axis. Woolson offered an alternative to the prevailing North-South reconciliation formulas by rejecting both carpetbag reclamations of the South and resurrections of a cavalier ideal. Instead, her emphasis on Florida as a place of endless acculturation paved the way for a reception of the newly emancipated slaves.

Woolson’s second strategy used the open-ended travel sketch to focus northerners on the freedpeople and recognize their rightful place in Florida’s cultural, political, and economic life. Having caught the prospective sojourner’s eye, her travel pieces gave voice to the aspirations of Florida’s freed men and women and their treasured sense of freedom. She reassured anxious northerners that freedpeople could transition to citizenship productively by describing the state’s other ethnic residents, notably the Minorcans, immigrants from one of Spain’s Balearic Islands, who transitioned from indentured servants to independent citizens. The Minorcans, particularly Minorcan women, served as a role model for freedpeople as they engaged in various profitable cross-cultural economic and social exchanges.

In her third strategy, Woolson substituted a work ethic suitable to Florida’s challenging climate and landscape for the northern, gendered work ethic. In doing so, she was sensitive to contemporary tensions between the rights of laborers and fears of vagrancy and dependency on poor relief. Woolson tackled freedpeople’s transition to free labor by highlighting the economic relationships already forged among all kinds of Floridians, and not simply on sectional cooperation; hers was a Reconstructive voice that helped rehabilitate the region. She highlighted Minorcan women, in particular, who challenged gender and ethnic subordination in becoming enterprising workers. In their casual approach to earning a living, Woolson’s Minorcan characters collapsed the distinctions between labor and leisure, being debated in publications such as the Florida Facts illustration.

As a corollary to her free-labor vision, Woolson presented a few select black characters who succeeded admirably as professionals and artists. These characters were inspired by her free-labor vision, the trend toward developing professions, and the recognition of workers’ rights. She emphasized the right of the ex-slaves to choose the terms of their labor, arguing for their independence, dignity, and freedom in making work arrangements.

At the same time, Woolson was keenly responsive to the rapidly changing literary marketplace, which was driven by reader interests and editorial demands. Woolson’s travel writings reflected northern ambivalence over acknowledging freedpeople as American citizens, a tactic that registered with conservative readers. Inherent within each of her strategies for reconstructing a place for freedpeople as citizens are moments of hesitation, contradiction, and even reactionism. These moments are characterized by a range of literary devices Woolson deployed, including fateful plot turns and some stereotypical portraits of freedpeople, Minorcans, and other migrants to Florida. The timing of her work in the marketplace, compounded by her literary choices, also helped diminish the opportunities for the ex-slaves and migrants to assimilate.

Specifically, Woolson’s portraits of freedpeople sometimes dismiss their rights and desires. While her travel sketches promoted tourism, her short stories and some of her poems positively discouraged readers from residency by highlighting the plight of migrants who end up consumed by the state. This consistently negative portrayal of residency had decisive ramifications, particularly for freedpeople eager to become property holders. Stressing the dangers of the ubiquitous swamp, Woolson showed Florida’s land not to be a worthwhile investment for freedpeople seeking to acquire property, a traditional means of citizenship. She further resisted portraying freedpeople as influential consumers whose newfound purchasing power could assert their citizenship rights against disfranchisement, a strategy popular with other Reconstruction writers. Her unflattering, occasional portrayals of lazy Minorcan men, of inevitably disappearing Native Americans, and uneducated freedpeople also undermined her endorsement of Reconstruction’s ideals by catering to fears about intermarriage. Finally, the most damaging consequence to her vision of Reconstruction was that her reassuring portrayals of independent freedpeople misled readers into believing that federal occupation was no longer necessary. The appearance of her magazine articles during the late 1870s may have inadvertently damaged the hopes of freedpeople, whose interests were already compromised by the lawless violence of this frontier district.

Woolson, Magazines, and Florida’s Postwar Travel Boom

Woolson made her first visit to Florida in 1873, along with her recently widowed sister, hoping the climate would help their ailing mother. The state had become a mecca for such convalescents. Woolson believed that a landscape’s recuperative power could also reconstruct its beholders’ identities; she was drawn to Florida’s balmy prospects and considered retiring to its remote, wild backwaters. Before quitting the United States for Europe, she wintered in Florida until her mother’s death in 1879. Fantasizing that she would like “to turn into a peak” when she died, Woolson believed then that people were, finally, what they saw, and she offered ailing readers a chance at recovery through her writing, particularly her travel sketches. Woolson, an admitted northerner and Republican, greatly preferred Florida to other southern states because she enjoyed its cosmopolitan flavor that brought together people from all “points of the compass,” which she highlighted in all her work.2

Woolson was neither the first nor the only one to transform Florida into a healing tourist paradise. An eclectic group of reformers came together in Fernandina and Jacksonville at the war’s close, keen to both develop Florida for northern tourists and help freedpeople realize their citizenship through mission work, education, and agricultural reforms. Tourism, as John Sears argues, had “played a powerful role in America’s invention of itself as a culture” since the 1820s, when there were monied citizens with enough leisure to take advantage of an improved transportation system.3

While the circumstances of Woolson’s time in Florida may make her seem part of the stampede of “sick Yankees in paradise,” as Nina Silber puts it, her work did not help “to soften and sentimentalize the ‘negro problem,’ ” as Silber claims travel writing did. Silber believes such writing tended to portray freedpeople as little more than picturesque appendages to a feminized, ruined landscape. She conjectures that the South was an escape from northern ills, rendering it, in her words, “devoid of political content.” However, Woolson’s writing, in trying to solve the “problem” to everyone’s satisfaction, recharged Florida’s scenery with meaning and made it crackle with political intent.4

Indeed, the Reconstruction of Florida began with words, since the state largely lacked the agricultural and export revenues that other states soon reestablished after the war. In guidebooks and magazines, this region was deliberately repackaged from being a military district of sectional and interracial conflict to an inviting resort. As one Florida guidebook writer put it, “the press is a great power to build up the ‘waste places,’ and the people cannot afford to hinder its growth among them.” Florida promoters advocated transplanting Yankee capital and labor to Florida to jumpstart the state’s postwar economy. Travel writers made economic development of the state’s resources increasingly dovetail with the tourist industry by, for example, making steamboats on the Ocklawaha River part of “the packaging of nature.”5

Magazines were an integral part of the tourism boosting Florida’s development and helped promote sectional reconciliation. Beginning with the newly launched Appletons’ Journal, Florida became a key literary property over which magazines waged battles. Drawing on extant tourist interests, the magazine featured a tour up the St. Johns River in a travel sketch that inaugurated its successful Picturesque America series on 12 November 1870. Woolson soon contributed to this enormously popular series, which helped transform war-torn southern landscapes into prized subjects for national art and best-selling periodical literature.6

Although Woolson began publishing her Florida work in Appletons’ Journal, her southern material was primarily published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, whose long-standing editor and distinguished man of letters, Henry Mills Alden, was particularly close to her. A little over a decade after its 1850 founding, the magazine had a circulation of around 200,000 in the United States and could boast of the widest readership of any magazine of its kind, largely because of its serious focus on travel. While the magazine’s editors did not especially boost southern writers until the late 1880s, they did adopt a postwar stance of reconciliation and neutrality toward the South to meet the intensified competition from the postwar debut of Scribner’s Monthly, Galaxy, and Appletons’ as well as New York’s Putnam’s and Philadelphia’s Lippincott’s. All five, but especially Lippincott’s, became more cordial to southerners as publishers quickly came to see in southern travel pieces a lucrative educational tool. Within this competitive context, Woolson’s publishing record with Harper’s New Monthly attests to her success in providing images of Florida to mollify and acculturate, rather than antagonize, her northern readers.7

Woolson’s writing about Florida began with poetry. “Dolores” appeared in the 11 July 1874 issue of Appletons’ Journal and was soon followed by “At the Smithy,” appearing in the 5 September 1874 issue. Next, “The Florida Beach” was featured in the Galaxy in October 1874. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine ran both “Pine Barrens” and “Matanzas River” in December 1874 and “The Legend of Maria Sanchez Creek” in January 1875. In addition to “Black Point,” which appeared in Harper’s in June 1879, Woolson published four stories set in Florida at the tail end of Reconstruction: “Miss Elisabetha,” in Appletons’ Journal on 13 March 1875; “Felipa” in Lippincott’s in June 1876; “Sister St. Luke” in the Galaxy in April 1877; and “The South Devil” in the Atlantic Monthly in February 1880. These latter stories soften the otherwise grim picture of bankrupt southern cavalier ideals found in her 1880 collection Rodman the Keeper: Southern Sketches. This collection also boasted a title which confounded the distinction between fiction and reportage, one which critics weighed in evaluating Woolson’s literary achievements as a balance between artistry and actuality.

Although consistent with other women travel writers who celebrated Florida’s inviting atmosphere of “gendered freedom,” Woolson departed from conventional formulas that prevailed in travel writing about Florida. Historian Susan Eacker identified three motifs that characterize postbellum travel writing on Florida: the “edenic, the exotic, and the exaggerated,” which Woolson tended to resist, especially the “exaggerated.” While some reviewers of the 1870s, notably those writing for the Nation, criticized women writers’ input on Reconstruction politics, an area in which they were told they had no rightful place, the frequent appearance of Woolson’s Floridian work in magazines suggested otherwise. The record of Woolson’s views about Reconstruction outside of her magazine work is slight; therefore, it is from her published work that one deduces an explanation.8

Many critics were consistently impressed with her southern stories as a perceptive contribution toward Reconstruction. A reviewer for the Atlantic Monthly marveled at the “strangeness” of her characters, concluding that Woolson had “at least pointed out a region where much can be done, and where she can herself do good work.” A Scribner’s critic carped that Woolson’s northern tourist “appears as a deus ex machina” amid “forlorn and broken lives” whose suffering has been “needlessly prolonged by the thievish rule of the carpetbaggers.” Nevertheless, he enthused, “It is impossible, after having read her book, to doubt that the South is just as she pictures it.” In coupling an admiration for her exotic setting with her characters, William Dean Howells singled out “The South Devil”; sensing Woolson’s reunionst sentiments underneath her sympathy for southern suffering, he concluded her work is “necessary” to those who “would understand the whole meaning of Americanism.”9

Woolson’s travel sketches cluster around the years 1874 to 1876, between the poems and the stories about Florida she wrote over her six years in the state. Her work found a ready audience as northerners began to flock to Florida after the war, despite the often violent resentment of some white residents. Her first sketch, “A Voyage to the Unknown River,” appeared in Appletons’ Journal on 16 May 1874. This was soon followed by her most substantially developed sketch, “The Ancient City,” which was published in Harper’s New Monthly in two parts in December 1874 and January 1875. Harper’s published her final Florida sketch, “The Oklawaha,” in January 1876.

Florida and the Freedpeople: Survival on a Lawless Frontier

During the years Woolson resided in St. Augustine, the state gained a public image of extremes. That Union-occupied city was already noted for its pitched sectional sympathies during wartime, combining the “bitterness of Confederate zeal with the warmth of Unionist welcome.” Like other defeated southerners, Floridians resisted Reconstruction, beginning with the 1865 suicide of its Confederate governor John Milton and his successor’s theatrical inauguration to the tune of “Dixie.” The state, with a population of only 3.4 inhabitants per square mile in 1877, was known to be a lawless frontier that harbored vigilantes. Unlike other southern states, Florida also was without a statewide system of political patronage to help provide order. Plagued since 1868 by factionalism and leadership dispersed over isolated areas, the state’s Republican Party was not equipped to protect freedpeople’s interests. In fact, the majority of Radical Republicans holding office during Reconstruction were black and white carpetbaggers, many of whom had flocked to Florida to speculate in railroads and the state’s natural resources. Testifying before the Joint Committee on Reconstruction in 1865, customs collector John Recks maintained that “the only way for this government to ma...