![]()

Chapter One: The Emancipatory Moment

The middle years of the nineteenth century brought to New Granada disease and death, turmoil and renewal. This much was known to the people “from the poorest class” of the Caribbean town of Sitionuevo, where they forced their mayor into flight one August day in 1849. The townsfolk, wracked by cholera, had demanded medicine to alleviate the distress of their families, and when they were met with official indifference, they flashed blades, broke into the homes of wealthy residents, and destroyed furniture. Men and women then turned to other targets, giving “machete blows to the doors of the tax collector’s house” and ransacking the town’s supply of tobacco, “shouting out that now it would be sold for one real per handful.” Troops soon arrived from surrounding districts led by Pascual Gutiérrez, a local jefe político, who upon entering Sitionuevo hailed the first man he met, “a black youth named Eusebio ‘La Pulga’ García, native of that city.” After Gutiérrez demanded that La Pulga submit to his authority, the youth allegedly attacked him with a machete, prompting the officer to shoot him in the leg. Although La Pulga and others were arrested, and a detachment of soldiers remained to help reinstate the ousted mayor, Pascual Gutiérrez remained apprehensive about the restoration of the old order. While the rioters had not physically harmed anyone, they had seized and destroyed a great deal of property. “If those in the uprising had had more time,” the jefe político warned, “who knows how far they would have taken their projects.”1

The protestors’ willingness to upend property and authority in assertion of their right to live free from misery was one instance of the dramatic transformation that swept across New Granadan society in the decade after 1848. Just four months before the Sitionuevo protest, a new national government had come to power in Bogotá under José Hilario López, a general, diplomat, and former governor of the Caribbean province of Cartagena. In its bid to establish legitimacy, the López administration turned back to the provinces, where demands for political change flourished after the election and where new alliances between national leaders and local groups produced significant shifts. In the law, liberals (and, on occasion, moderates and conservatives) pushed through a host of reforms over suffrage, marriage and religious rights, jury trials, and local autonomy in the name of equality and liberty. The formal expansion of citizenship rights, culminating in the 1853 constitution, encouraged further protests like those in Sitionuevo. And although legal changes could not alleviate the immediate hardship underlying such protests, they did often validate projects far beyond the letter of the law.2

The conditions that enabled reforms and popular mobilization under López and his successors were fortified by the imminent destruction of slavery. In New Granada, cimarrones (fugitive slaves) hollowed out institutionalized bondage through flight into the country’s backlands. By the time Congress passed the final emancipation act in May 1851, which went into effect on 1 January 1852, slavery was all but a dead letter, the political costs diminished by a national antislavery consensus and by the actions of the slaves themselves. Even as slaveholding faltered, liberal and democratic reformers of the López administration staged public manumission ceremonies before mass audiences to disseminate egalitarian citizenship and promote their faction’s legitimacy. The significance of these spectacles—freeing slaves to promote the López administration and its role in abolishing slavery—went beyond partisan calculus. The libertarian and egalitarian impulse behind slave emancipation became the basis of a new ethos that shaped law, governmental administration, and public interactions between citizens. The fusing of liberal citizenship to slave emancipation stamped the decade with a host of experiments in democracy, as citizens used legal freedom to challenge prevailing ideas of racial, marital, and economic status.3

Yet despite the consensus to end slavery, New Granadans reached little agreement over the consequences of legal freedom and civil equality. The attempt to sculpt citizenship out of emancipation quickly ran into disagreements over its content and beneficiaries. The mass mobilizations and ethos against discrimination built from abolitionism soon disrupted the tenuous compromise between the progovernment Liberals, their Conservative opponents, artisans, and enfranchised plebeians in the provinces. While some groups were apprehensive about the scope of change, many Caribbean citizens pushed for fundamental redefinitions of equality and authority not always anticipated by political leaders.4 Provincial protests that the López faction had sought to channel for political support were not easily contained. In April 1854, a military coup supported by many coastal citizens overthrew the national government. The Melista coup, as it was known, became a major contest for democratic citizenship, and its resolution—in particular, the first vote under rules of universal manhood suffrage, held in 1856—left behind more uncertainty over recognition for those who had helped create that citizenship in the first place.

FREEDOM’S BURDENS

Emancipation came to New Granada gradually and principally through the efforts of individuals who fled their enslavement. Some slaves sought liberation through self-purchase, although barriers to such efforts were formidable, and economic decline after independence constrained their opportunities for earning freedom wages. Instead, many more escaped into the forests and remote valleys of the Caribbean and Pacific coastal frontiers, a steady movement of population beginning in the colonial era that accelerated under the social disruptions of the wars of independence and succeeding years of unrest.5 In the first half of the nineteenth century, as the older Caribbean population centers of Cartagena, Santa Marta, and Mompós endured hard economic times and outmigration, to the benefit of the younger and more commercially dynamic settlement of Barranquilla, urban and hacienda slaves also found opportunities for escape and mobility in newly opened terrain.6

One consequence of flight was the rise of new settlements in the coastal backlands. Smallholdings dotted the landscape where individuals and families built simple huts and developed garden plots on which men felled trees, fished, hunted, and raised livestock; while women and children tended fields of corn, bananas, manioc, sugarcane, and rice. Travelers often witnessed women and men along waterways guiding boats full of produce on the way to local markets, and they noted that women maintained independent livelihoods and sustained families by making straw hats, reed mats, and other handicrafts. Women’s active and visible role in marketplaces allowed families to acquire essentials that could not be self-produced and bolstered relations between widely dispersed settlements.7 Exploiting land, water, and forest for subsistence or barter minimized the reach of outside employers, former slaveholders, and urban government. As part of a hemispheric movement of people out of bondage, escaped slaves in New Granada looked to a hardscrabble existence on the land to fashion new forms of kinship and labor.8

The movement toward freedom by means of individual flight and physical resistance deepened already tangled relations between slave and free in the Caribbean region. After independence, the few remaining people in bondage lived in both coastal towns and countryside among a vast free population of African descent. In Minca and San Pedro in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, “blacks and slaves” worked together on haciendas owned in the 1830s by Joaquín de Mier, “the wealthiest merchant of Santa Marta.” The seeming ease with which laborers could flee these locales, at times absconding with slaveholders’ animals and other movable property in the process, may have dampened abolitionist calls.9 At other moments, slave resistance inspired free people to agitate alongside bondmen and -women, as in July 1833, when individuals on a hacienda near Cartagena hacked to death their English slaveholder, his wife, and his son. After the bodies were taken to the city, an “immense multitude . . . composed of slaves and persons of color of the lowest class” rioted on Cartagena’s wharf and prevented officials from removing or even inspecting them. In these moments democratic rhetoric in circulation since independence may have raised expectations of further change, encouraging slaves and free people separately or collectively to challenge myriad forms of social domination.10

The relationship between the enslaved minority and free majority was further complicated by flight as a movement by and large of the already-free. Squatters and fugitives were in the majority not escaped slaves, yet they all followed similar paths into the coastal backlands to establish settlements or inhabit existing ones often founded by earlier generations of escaped slaves. Despite penalties in the early republic for the “mulatto or black who harbors a runaway slave,” keeping them apart proved impossible once individuals reached the backlands.11 In the rural hideaways, remarked one foreign diplomat, status distinctions blurred, as nearby de Mier’s Sierra Nevada haciendas were communities of “poor Indians” and “lazy blacks” that were otherwise similar in being “little stimulated by the needs of material life.”12 By the middle of the century, entire swaths of the countryside were in the hands of motley groups of runaways. One jefe político along the Dique Canal southeast of Cartagena warned his superiors about this social world in early 1850, when he reported on two haciendas abandoned by their owners that “are today rochelas for other escaped slaves, deserters, fugitives, etc., on which they do not cease to commit scenes that cannot be stopped because only with armed force would it be possible to assault and capture them without risk.”13

Slaves joined the free in mass flight because the country’s political leadership in the three decades after independence expressed general reluctance over emancipation. New Granadan officials defined abolition as a gradual process to be controlled by governors or, better yet, by the slaveholders themselves. In the earliest abolitionist measure, the Congress of Cúcuta passed the 1821 law of free birth and manumission, which raised expectations of freedom without providing it.14 The law established manumission juntas that functioned only intermittently, freed few slaves, and suffered significant financial and political constraints.15 Belated legislative efforts to stem the hemorrhaging of the slave population due to marronage and civil war only produced more fugitives. Reforms passed in the early 1840s that required former slaves to submit to an apprenticeship system under former slaveholders were an attempt to counter the accelerating pace of self-liberation, yet only those individuals with enslaved kin were likely bound by this unfree status.16 Between 1843 and 1849, when manumissions all but ceased and apprenticeship was the law, Cartagena’s and Santa Marta’s slave populations shrank by half. Whether New Granadan governments paid lip service to abolition or directly opposed ending slavery, the onus of emancipation fell to the slaves themselves.17

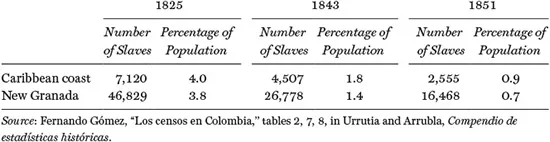

By 1850, only 17,000 slaves remained, comprising less than 1 percent of the national population, down from roughly 4 percent in 1825 (see table 1.1). In all but the sugar plantation zone of the Cauca Valley in southwestern New Granada, slaves made up a minute fraction of the total population. In some districts of the Caribbean coast where people of color had long predominated, slavery had disappeared altogether, and many rural districts were de facto free regions. Already in the late 1840s, slaves from Brazil were fleeing into New Granada, given the republic’s reputation, with some justification, as a sanctuary of freedom.18

If slaveholders and their allies wished to stanch self-liberation and flight, the midcentury mobilizations in the political arena, epitomized by the growth of the democratic societies, helped thwart such efforts. The democratic societies, with origins among Bogotá’s artisans in the 1830s, were revived and spread across the country in the late 1840s and early 1850s to provide men with little prior experience the means to participate in public affairs. The sudden popularity of these groups coincided with arrival of news of the 1848 revolutions in Europe, upheavals that inspired New Granadans across the political spectrum.19 In the dozen or more Caribbean cities and towns where citizens formed new societies, these groups tended to be composed of university-educated men, artisans, and landless laborers—peacetime forums unprecedented in their social diversity. One of Cartagena’s first such societies, founded in early 1850 by lawyers, military officers, and merchants, met at night to allow workingmen to attend, since its “objective” was “to moralize and instruct [the people].” The democratic society in Chinú, a savanna town south of Cartagena, similarly aimed to “serve as a political school for instructing the people in their duties and rights.”20 The intent of educating men on their citizenship began in society meetings but soon spread to the nascent public sphere. “Cobblers, as artisans, tend to your shoes,” exhorted a February 1850 editorial in a Cartagena newspaper, “but as citizens, tend to your rights and observe your duties.”21

Table 1.1. Slave Population of New Granada, 1825–1851

The democratic societies also performed a practical function as the political clubs to mobilize support for the presidential administration of José Hilario López. Although his candidacy was popular among many New Granadans, López did not win a clear electoral majority, and his eventual victory in March 1849 came under the cloud of a disputed vote by a deeply divided Congress. Subsequent reforms early on in his presidency, like the expulsion of the Jesuits, further galvanized conservative opponents, which compelled followers of the president to enlist popular sectors to shore up their faction’s political viability. As a shadow organization for López, the democratic societies issued broadsides and editorials to appeal to voters in Cartagena, and their leadership recruited adherents by horseback in Santa Marta.22 The societies’ noisy street rallies and clashes with political rivals, moreover, transformed their relatively poor members into the backbone of the ruling party. Conservatives in Santa Marta, in Mompós, in Cartagena, and throughout the country soon founded their own groups, known as popular societies, although on the coast they were never more than a fraction o...