eBook - ePub

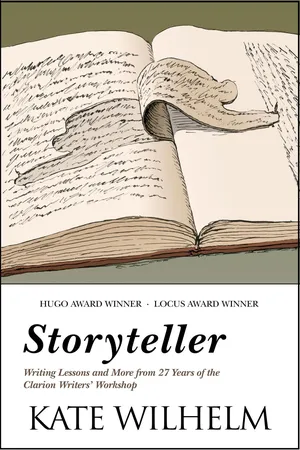

Storyteller

Writing Lessons and More from 27 Years of the Clarion Writers' Workshop

This is a test

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

“Wilhelm really knows students and knows how to teach them to craft a professional story.”— The Oregonian

Part memoir, part writing manual, Storyteller is an affectionate account of how the Clarion Writers’ Workshop began, what Kate Wilhelm learned, and how she passed a love of the written word on to generations of writers. Includes writing exercises and advice. A Hugo and Locus award winner.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Storyteller by Kate Wilhelm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Years Two and Three

We were back in the charming old resident dorm, still condemned, still empty except for our group. That year Jonathan had a tricycle, and he loved racing through the corridors, around and around in the lounge, and even in the women’s wing, where he announced his presence, calling out, “Man on the floor!”

I felt as if time had pulled off another magic trick: the intervening months had been snipped out. This was a continuation of the previous year. We were marginally better prepared, but not yet real teachers. We were still doing very little lecturing, leaving that up to Robin, who was so good at it. But I took a long story I had revised, and we talked about revisions—everything from simple wrong words to paragraphs added, to total rewrites starting with page one, word one. My edited manuscripts were a mess, with additions scrawled in the margins, continued on the reverse side, words and phrases struck out, others inserted illegibly. They still look much like that, in fact.

That year there was another ongoing summer workshop, a class in anthropology, the Diggers, being taught by a man whose degree was in social studies. He wore jodhpurs, high black boots with a mirror shine, and a pith helmet in the wilds of Pennsylvania.

The Diggers were even grimmer than our own students had been the previous year, and several of them began to hang out with our group. They came armed, ready to do battle, and they were accepted. Two of them left anthropology after that summer, went to California, and tried their hands at script writing.

Their instructor came searching for them one afternoon and spotted Russell Bates. “What tribe are you from?” he asked. Russell said Kiowa. The instructor grasped his chin, turned his head this way and that, and said, “You could be.” He invited Russell to come see his collection of Indian skulls. With admirable restraint Russell politely declined.

Russell had traveled to Clarion with a trunkload of fireworks. On the Fourth of July, the president of the college had an evening social, and while people were sitting around having a civilized conversation over their gin and tonic, there came a series of explosions. The party froze; the president turned livid, and our man on the spot, Robin, did not say a word, although he muttered under his breath, “I’m going to kill that Indian.”

Russell had led a group to the nearby cemetery, where they celebrated Independence Day.

We muddled our way through as before, a little better at explaining our critiques and generalizing from them. We invited the students to sign up for private conferences, but we did not demand that everyone do so. We had started to read all the previous stories, and we were prepared to talk about them as a whole, not just the stories we had workshopped. And we gave them the assignments we had worked out for examining their own stories, line by line, paragraph by paragraph, after they left Clarion. Without quite realizing it, we were laying the groundwork for what was to become our normal procedures in the following years.

We felt we had done a little bit better than before, but not enough better, and still did not know exactly what to do differently.

In the sixties I developed an allergy that affected my eyes and resulted in three surgeries. My ophthalmologist sent me to an ocular allergist in New York City—I had never heard of such a specialty before. That doctor failed to diagnose the cause of my problem, but he prescribed a desensitizing program—injections to be administered by my own doctor in Milford—and we all hoped that would take care of it. However, I reacted severely to the third shot, and my doctor refused to continue the program. At that time the only advice anyone could offer was for me to leave the area on the chance that the allergy was environment-caused.

We had completed that year’s Milford Conference and Clarion, and we decided to go to Florida for the coming winter. James Sallis, his former wife, and their child, along with Tom Disch, rented our house for the period. Both Jim and Tom had been frequent visitors, and it seemed ideal all around.

In Florida we rented a dilapidated two-story beach house in which we sat out a hurricane that fall. All day the weather advisories had said the hurricane would make landfall up in the panhandle, that the beaches would be subjected to high tides, but nothing more. Late in the day, with the streets flooded and water rising, a fire truck rolled by with a bullhorn advising immediate evacuation. The storm would come ashore a few miles north of Clearwater, thirty miles north of us. At the same time the television advisories were telling everyone not to drive on flooded streets, and not to attempt to cross any of the bridges to the mainland. Not exactly rock and hard place, but rather hurricane winds and flooding. Unable to drive out, we sat in the upstairs of our old house and alternated between watching rising water out the windows and Star Trek on television, interrupted continuously by new advisories.

The water rose to the doorsill, stopped, and gradually subsided. We knew how lucky we had been.

That fall and winter, my eye problem vanished, and we had a very hard decision to make: try Milford again and hope there was no recurrence, or remain in Florida. We opted to go home.

We returned in time to do Milford, and later to go back to Clarion for the third time. We found changes that year. We were still in the condemned building, but the students were housed in different quarters: a bleak and loveless concrete block building that had all the characteristics of a prison. The rooms were tiny and airless, there was no real gathering place, no wide porch and surrounding shrubbery for water gun battles; but there was a dorm manager who clearly did not approve of the workshop attendees and their unconventional behavior. Probably he did not approve of long hair on males, but that was never actually stated. He, of course, was called the Warden. Our group then—and for many years afterward—was eyed with suspicion. Robin told me that various people asked him who was that woman in blue jeans with the baby and what was she doing on campus. Damon with his long hair, I in blue jeans, rowdy students armed with water guns and superballs, none of us was quite proper, clearly out of place in an academic setting.

Nothing about the town had changed, and it still had little to offer in the way of entertainment and diversion. In spite of all that, the workshop was as successful as it had been previously, the students as talented, hardworking, and as determined as ever.

By the third year, it was undeniable that the workshop was doing something right. Former students were writing stories, selling them, getting published. Many of them were becoming professional writers. What combination of talent, teachers, environment, and dedication proved the potent magic mix was impossible to tell, but it was effective then and on through the years. We suspected that the array of teachers, each one bringing a different perspective, demanding quality work, concentrating on whatever aspect of writing that particular writer-teacher saw as of primary importance, had a great influence on the success of the workshop as a whole.

During the long talks we had had over our roles, Damon and I came to realize that many of the students had no clear understanding of what was meant by a short story. We decided that would be our starting point that summer. After all, the workshop was for short story writers.

A short story is a narrative work of fiction under an arbitrary length that is variable depending on who is counting and for what purposes. For the genre-writing awards it is accepted that the cut-off for short stories is 7,500 words. A novelette is from 7,500 words to about 15,000. A novella is from 15,000 to 40,000 words, and a novel is 40,000 words and up. Although they all share the term narrative fiction, they differ substantially.

A novel opens a door into another world and invites the reader to enter and explore it with the writer. Whether the other world is on a different planet, in a different period of time, or is placed here and now, it is always a different world. Each writer interprets the experienced world differently; no two are exactly alike. Actually the only new thing writers have to offer is their own perception of a world as it exists or is imagined.

In the novel, plots and subplots and usually many characters are developed and often many viewpoints are used. There is no time or space restriction; the writer is free to wander through the past, the present, the future, and roam the entire universe if the novel requires it. A novel is a forgiving form of fiction and for many reasons, excluding length, the easiest to write.

A novella usually has one main story line that is developed thoroughly, with minor subplots that are often hinted at rather than explicated. The novel opens a world; the novella opens a piece of it. Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea is a good example. Much of Henry James’s work is in the novella form. There can be several characters who weave in and out of the main story line with their own viewpoints taken, and even minor subplots explored.

A novelette is more restricted, usually has one main character, and a story line that is followed from start to finish with few diversions. The form allows for room to explore yet a smaller piece of the world, only that part that is important to the story, although that abbreviated part may be well developed.

A successful short story is a marvel of compression, nuance, inference and suggestion. If the novel invites one to enter another world, the short story invites one to peer through a peephole into the world, and yet the world has to have the same reality as in a novel. It truly is the universe in a grain of sand. This is done by compression and implication. Every single word has to help the story, or it hurts it. The short story is the least forgiving form of narrative fiction, with no room for redundancies, for backing up to explain what was meant before, for auctorial intrusions that may be perfectly allowable in the novel.

That is one reason why the flashback, useful in novels, is most often a mistake for the short story. There is not enough space allowed to go over the same territory twice. Again and again students applied novelistic techniques to the short story, and failed invariably.

In the short story, there must be the moment of truth. There must be something important at stake for the characters within the world of the story to which they react in meaningful ways; or there has to be a moment of truth in which the reader comes to realize what is at stake even if the story characters remain oblivious. Someone has to react to the moment of truth of the story.

If there is no moment of truth, if the choice before the hero is between vanilla and chocolate, the story is trivial. An anecdote, no matter how cute or charming, is trivial in this context. A character study is most often trivial. That came to be one of the most dreaded words of the workshop, that single word trivial written on the manuscript. Damon’s So what? was possibly even more devastating.

Up until and even including the third year, Damon and I reacted to the stories, explained our reasoning as best we could, and moved on. Sometime during that third year, too late to do much about it, we came to the realization that our approach had been wrong from the start. As I mentioned earlier, we had been treating these beginning writers the way the professional writers at the Milford Conference treated each other, and we found that not only was it not appropriate, but it likely was confusing, as well. With professional write...

Table of contents

- » Preface

- In the Beginning

- Can Writing Be Taught?

- Years Two and Three

- Supporters

- Delegations and

- Let the Wild Rumpus Begin

- Who Is That Masked Man?

- Where Am I?

- What’s Going On?

- Body Count

- Please Speak Up

- Beyond the Five W’s

- The Days

- » Notes and Lessons on Writing

- » Writing Exercises

- About the Author

- About Small Beer Press