This is a test

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

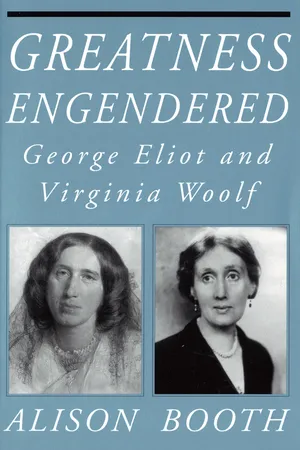

The egotism that fuels the desire for greatness has been associated exclusively with men, according to one feminist view; yet many women cannot suppress the need to strive for greatness. In this forceful and compelling book, Alison Booth traces through the novels, essays, and other writings of George Eliot and Virginia Woolf radically conflicting attitudes on the part of each toward the possibility of feminine greatness. Examining the achievements of Eliot and Woolf in their social contexts, she provides a challenging model of feminist historical criticism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Reading Women Writing by Alison Booth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism for Women Authors. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Something to Do: The Ideology of Influence and the Context of Contemporary Feminism

Feminist critics have turned eagerly to both Eliot and Woolf as magnificent contradictions of all those prohibitions against women in the sanctum of art—“Women can’t paint, women can’t write,” says Charles Tansley to Lily Briscoe (TL 75)—yet they are often disturbed to find in the novels an insistence on the suffering and silence of women. The authors appear to declare the rights of women to a place in history, yet also to depict that place as an obscure, retiring one. What presuppositions about the nature of womanhood and sexual difference governed their fiction as well as their writings on womanhood, on women’s education and vocation, and what gender ideology guided their own rather reserved association with women reformers? The answers I offer to these questions suggest the need for a more fully elaborated ideological history of the women’s movement. Instead, I can only trace here some especially intriguing intersections of Eliot’s and Woolf’s ideology of influence with that of some contemporaries.

Eliot and Woolf on the Nature of Womanhood

Like most nineteenth-century partisans of women’s interests and like many feminist factions today, these English women of letters waffle in the debate about nature versus nurture. On the one hand, their narratives can be shown to undermine the illusion that historically conditioned differences in gender are natural and inevitable. On the other hand, they can be caught again and again conflating biological sex with cultural gender, smuggling into their texts a sentimental belief in the inherent and timeless (if not literally innate) femininity—and superiority—of women. Why this fondness for what we would grandly call “difference” persists among some of those who have speculated most profoundly about sexual roles is an intriguing question, since a mystified “womanhood” has been the shibboleth of oppression. But it is certainly true that Eliot and Woolf both leaned toward this mystified difference.

Eliot and Woolf are in good company in their desire to preserve some aspect of the “nature” of womanhood from the effects of historical conditioning; the many feminists who have resisted seeing difference as an entirely historical construct have shared at least one compelling reason for doing so (besides the obvious—itself historically conditioned—basis of biological sex). If culture were entirely responsible for a perceived femininity, what would become of the virtue of not resembling the patriarch in the event that all oppressive conditions were rectified? If everyone were “like men,” aggressive, calculating, power-hungry (and in many Victorians’ view, uniquely sex-hungry), etc., etc., history would be a merciless chronicle. Hence the temptation to invoke what I call the ideology of influence: a belief that women have a direct line to the sources of human emotion, and that their self-sacrificing love (or in a current version, their interest in relationships rather than power or justice) “mitigates the harshness of all fatalities,” in Eliot’s words. This ideology of influence, which came into full flower after the 1830s as industrialization exaggerated the division between men in the workplace and women in the home (or in underpaid, segregated labor [Hartmann 207–13]), sought to redefine womanhood as a mission rather than a mere handicap. Thus, even if one protested the sacrifice of “many Dorotheas,” one could without sense of treachery exalt the influence of the women sacrificed (M 612). The alternative might be no alternative, or alterity, at all. The norm of masculine egotism, of a struggle for domination in the political and economic realm, might govern all human existence. The logic of polarities thus generates a mystified historical other, even as those who invoke it try to reach beyond polarities: women’s influence is toward reconciliation, what Eliot envisioned as a harmony of the sexes, and Woolf as an androgyny beyond sexual self-consciousness.

Eliot’s writings exhibit all the ambivalence of her contemporaries when they criticize the historical position of women yet defend the special qualities of influence. Eliot’s earlier writings, preceding the more widespread agitation for women’s causes in the 1860s, show more inclination to hasten the progress toward equality of the sexes that she assumes is inexorably underway. At times claiming that women exert “a conservative influence” almost by nature (“The Natural History of German Life” 275), she nevertheless succinctly states the case for a cultural view of the “sex/gender system” (Rubin 168) when she acknowledges the radical innovations of such women as Margaret Fuller and Mary Wollstonecraft. An oppressive society has created feminine inferiority:

On one side we hear that woman’s position can never be improved until women themselves are better; and, on the other, that women can never become better until their position is improved. … But we constantly hear the same difficulty stated about the human race in general. There is a perpetual action and reaction between individuals and institutions; we must try and mend both by little and little. … Unfortunately, many overzealous champions of women assert their actual equality with men—nay, even their moral superiority to men. … But we want freedom and culture for woman, because subjection and ignorance have debased her, and with her, Man. (“Margaret Fuller and Mary Wollstonecraft” 205)

It may seem promising here that Eliot will not overzealously claim women’s moral superiority, and that she calls for a wider field of endeavor for women because they have been defined by oppressive customs; whatever the nature, nurture has much to answer for (compare Lewes, “Lady Novelists,” 7).

Eliot has little love for idolized women as they are. Thus she praises Wollstonecraft and Fuller but objects to that domestic monstrosity, the “doll-Madonna in her shrine”; warbling in her gilded cage like Rosamond Vincy, she is often a harpy who debases a “man of genius.”1 Indeed Eliot can be almost as hostile as Woolf toward the Victorian domestic idol, the Angel in the House, though Eliot follows tradition in commiserating with the Angel’s husband rather than her daughters. Hints of direct conflict with the feminine ideal, however, make Eliot uneasy. She cannot kill the Angel in the House as Woolf advises the woman writer to do; she merely condemns her to a hell of falsity and selfishness.

It seems that Eliot cannot sustain her historical analysis of gender and the subjection of women. When women verge on Romantic egotism, she tends to revert to arguments of innate femininity. She praises the “brave” and “strong” Margaret Fuller and Mary Wollstonecraft because they are not the demon opposites of household angels: they still listen to “the beating of a loving woman’s heart, which teaches them not to undervalue the smallest offices of domestic care or kindliness” (201; compare Woolf on Wollstonecraft, “Four Figures,” CE 3: 193–99). Here we suspect a sentimental association of women’s innate tendencies (“heart”) with domestic self-sacrifice, only in a more active and unselfish mode than the doll-Madonna’s. Eliot’s ideal woman’s role might be called the domestic public servant: a woman ministering to human need in the marginal realm of charity or social causes, whereby, for example, the hospital can be seen as the household sickroom “multiplied.”2 Her own role as novelist likewise bridges the private moment of the reader at home and the public domain of epochs in the national life, as well as the massive “public” or audience conjured up by her novels. (In N. N. Feltes’s Althusserian interpretation, Eliot “interpellated a special audience,” as she won her bid for “professional status,” in part by “displaying publicly” her unwomanly individual rights [49].) Thus the apparent egotism of the public woman, from Wollstonecraft to herself, may be exonerated if the woman’s “heart” still conceives its vocation in domestic terms (Homans 153).

An appeal to the womanly “heart” was almost universal in Victorian writings on the woman question, but it was sometimes accompanied by a less essentialist conception of women’s role, especially among the women and men who like Eliot were familiar with the ideas of Spencer, Comte, John Stuart Mill, and others associated with the Social Science Congress (Myers, Teaching of Eliot, 5–9). Eliot’s interest in developmental or evolutionary social science helped her to call attention to cultural variations, as when she notes the achievements of cultivated French women during the Enlightenment (“Woman in France: Madame de Sablé” 54, 58). Yet this same empiricist bias betrays her when she too readily attributes biological origins to perceived characteristics. Eliot would undoubtedly have concurred with John Stuart Mill when he noted in The Subjection of Women that “unnatural generally means only uncustomary” with regard to sexual roles; yet we see in her works an unacknowledged clinging to what Mill calls the “moralities … and … sentimentalities” that tell women “it is their [duty and] nature, to live for others” (22, 27).

For Eliot, the idea of a biological burden is readily transposed into a moral mission. As she wrote to John Morley in 1867 apropos of the debate over Mill’s amendment for the franchise for women,

I would certainly not oppose any plan … to establish as far as possible an equivalence of advantages for the two sexes, as to education and the possibilities of free development. … I never meant to urge the ‘intention of Nature’ argument, which is to me a pitiable fallacy. I mean that as a fact of mere zoological evolution, woman seems to me to have the worse share in existence. But for that very reason … in the moral evolution we have “an art which does mend nature”—an art which “itself is nature.” It is the function of love in the largest sense, to mitigate the harshness of all fatalities.

The “zoological” difference between men and women is a boon in that it teaches humanity to recognize its own progress toward “a more clearly discerned distinctness of function (allowing always for exceptional cases [such as herself?]…),” while the inequalities of this difference are “a basis for a sublimer resignation in woman and a more regenerating tenderness in man.”3 Nature, or the womanly art of love which is nature, seems to be the only certainty in a tenuous struggle toward “equivalence of good for woman and for man.”4 Thus the “pitiable fallacy” of biological destiny creeps back in in spite, or because, of an attempt to represent women as active partners in human progress. Without innate difference, and hence without the need for “resignation,” Eliot implies, there would be no regeneration for men, nothing but harsh fatality.

Eliot wrote similarly equivocal pronouncements to her friend Emily Davies, the pioneer of women’s higher education, during the height of the struggle to found Girton, the first women’s college affiliated with “Oxbridge.” The letter begins with a self-censorship that is also weighty advice to the woman who will be addressing the public:

Pray consider the pen drawn through all the words and only retain certain points … as a background to all you may … say to your special public.

1. The physical and physiological differences between women and men. … These may be said to lie on the surface. … But … the differences are deep roots of psychological development….

2. The spiritual wealth acquired for mankind by the difference of function founded on the other, primary difference; and the preparation that lies in woman’s peculiar constitution for a special moral influence. In the face of all wrongs, mistakes, and failures, history has demonstrated that gain. And there lies just that kernel of truth in the vulgar alarm of men lest women should be ‘unsexed’ [by education]. We can no more afford to part with that exquisite type of gentleness, tenderness, possible maternity suffusing a woman’s being with affectionateness, … than we can afford to part with the human love, the mutual subjection of soul between a man and a woman—which is also a growth and revelation beginning before all history.

… Complete union and sympathy can only come by women having … the same store of acquired truth or beliefs as men have, so that their grounds of judgment may be as far as possible the same. (GE Letters 4: 467–68)

Here Eliot envisions historical change—increasing education for women—as a means of restoring a kind of Platonic, pre- or ahistorical union between man and woman. At the same time she cannot resist the vulgar anxiety to preserve a feminine ideal that depends on separate “grounds of judgment.” Like Mary Wollstonecraft, in other words, Eliot would have males and females educated together in order to promote mutual understanding, but unlike Wollstonecraft (86, 107–9) she distrusts a monolithic, masculine norm for all human beings. What would we do without difference? Like the Victorian opponents of equal education whom Ray Strachey describes, Eliot wishes to preserve “that special and peculiar bloom which they regarded as woman’s greatest charm, … that valuable, intangible ‘superiority’ of women” (Strachey 143). Eliot’s sibilant words, “gentleness, tenderness, possible maternity suffusing … with affectionateness,” seem nervous approximations of an ideal very much like Ruskin’s in “Of Queen’s Gardens.”

But Eliot is not quite the advocate of arrested female development that this likeness to Ruskin and the guardians of bloom suggests. It is less the intention of nature that concerns Eliot than the intention of women: they must retain their selflessness to mend the “hard non-moral outward conditions” that men more directly contend with (GE Letters 4: 365). In The Mill on the Floss, at least in the early books, Eliot treats the notion of womanly “bloom” with bitter sarcasm, disparaging the system that prevents Maggie from learning Latin. But the novel implies that if a masculine education cultivates the sword-swinging and cruel “justice” of her brother Tom, Maggie is better off learning through her suffering.5 Most readers undoubtedly side with Maggie, though we may resist the novel’s pressure to concur in her sacrifice.

This sympathy for Maggie is not only a rhetorical effect, I believe, but also an effect of prejudice in favor of the feminine: many of us still feel the attraction of the myth of the “intangible ‘superiority’ of women.” Less dubiously, I think we need not be ashamed of wishing to see “gentleness, tenderness, … affectionateness” incarnated in powerful forms, preferably female and male, without the prescription that those born female must be more selfless than those born male. Bloom and influence are deeply sinister ideals as the strategies of the marginalized, but it would be misguided therefore to value only self-interested plain-dealing on the masculine model. If most feminists now abhor the silent, disembodied lady of the Victorian imagination, they do not therefore repudiate all things “feminine” as though women must advance by becoming “manlike.” Eliot’s and Woolf’s defense of feminine or selfless heroism seems an attempt to escape the dichotomy between the man’s ability to exploit and the woman’s ability to remain chaste. If Maggie’s sacrifice to the flood and family history seems more disturbing than Miss La Trobe’s immolation, at the end of Between the Acts, in a flood of words for the sake of a new history of the human family, both can be seen as offering an escape from self that might also be an end to essentialized gender.

Woolf persists in the Victorian hopes for women’s education and the alteration of the nurture that has suppressed women, but she also shares the Victorians’ nostalgia for natural difference. In A Room of One’s Own she eulogizes “that extremely complex force of femininity” that has infused...

Table of contents

- Preface

- Frequently Cited Works

- Introduction: The Great Woman Writer, the Canon, and Feminist Tradition

- 1. Something to Do: The Ideology of Influence and the Context of Contemporary Feminism

- 2. The Burden of Personality: Biographical Criticism and Narrative Strategy

- 3. Eliot and Woolf as Historians of the Common Life

- 4. Miracles in Fetters: Heroism and the Selfless Ideal

- 5. Trespassing in Cultural History: The Heroines of Romola and Orlando

- 6. “God was cruel when he made women”: Felix Holt and The Years

- 7. “The Ancient Consciousness of Woman”: A Feminist Archaeology of Daniel Deronda and Between the Acts

- Works Cited

- Index