![]()

Chapter One

ENTER THE FILM BUFF

HOW DID IT ALL BEGIN? WHAT THEATRE AUDIENCE IN THE DAYS OF THE nickelodeon gave birth to the bona fide fan or buff? The term “buff” predates the motion picture by more than fifty years, originating in New York as early as 1820. Volunteer firefighters in the city wore buff-colored coats, and “buff” came into use to describe those who would follow the firemen and enjoy the experience of watching a fire and, in time, enthusiasts of all types. Enjoyment of a fire—whether caused by an accident or arson—suggests a level of maniacal fever, of which many film buffs might be accused. However, for more than half of the twentieth century, there was no linkage of “film” and “buff.” Although there might have been many descriptive terms in use for decades in reference to film buffs, they were never actually identified as such.

A number of terms developed to describe a fixation with the motion picture itself, including, rather obviously, “cinemania,” “filmania,” and “flickeritis.” Those fixated individuals were “movie-nuts,” “cinemaddicts,” “cinementhusiasts,” “movie-ites,” or simply “flicker fans.” Autograph collectors were identified as “autografans,” while male film enthusiasts briefly were identified as “reel boys.”1 Above all, they were autodidacts, self-taught in that there were no colleges or universities offering film courses to the first film buffs, and when such courses did materialize, they were generally beyond the means, both financially and intellectually, of an average film buff.

Just as there is no confirmed origin for the term “film buff,” or equally “movie buff,” so there is no precise definition. As of 2014, even Wikipedia had not posted an article using that exact term. WikiHow offers an eight-step program on becoming a film buff, which basically requires purchase of a film guide by Roger Ebert or Leonard Maltin, the viewing of lots of films, and the acquisition of DVDs from the cheapest sources available. There is no reference to such obvious film buff requirements as keeping lists, acquiring movie memorabilia, and attending film conventions, as well as deploring all remakes, approving of all silent films, and preferring blackand-white over color, unless such color happens to be in the form of an original Technicolor print from the 1930s or 1940s. A film buff can be many things to many people, and therein lies the problem of definition. Even the first usage is undocumented, with Collins English Dictionary suggesting that it dates back no further than the 1990s. But then the dictionary also defines a film buff as being a “connoisseur,” and that is something very much in doubt.

With ease, academics can provide such definitions as: “Fandom is a sociocultural phenomenon largely associated with modern capitalist societies, electronic media, mass culture and public performance.”2

Others might have some difficulty with such a ready-made comment. Film buffs would equally be nonplussed, undoubtedly wondering what the academic was talking about. “You talkin’ to me?” in the words of Paul Schrader/Robert De Niro. Or, to quote Ozzy Osbourne, “You looking at me?”

Print-wise, it would seem that “film buff” was seldom, if ever, used prior to the first half of the twentieth century. The earliest documented use of the term in any major newspaper is in the November 21, 1960, issue of the New York Times, in a piece about John Hampton, owner of the Silent Movie Theatre in Los Angeles.3 In December 1968, film critic Renata Adler asked in the New York Times if she was writing for the “film buff.”4 In the Los Angeles Times, the earliest reference to a film buff occurs on December 23, 1969, when film critic Charles Champlin (revered in the industry for seldom if ever reviewing a film he did not like) offered his selection of current film books, and managed to reference both “film buffs” and “film nuts” in the same piece.5 Presumably, the terms are interchangeable.

It was the Japanese who first came up with an appropriate phrase applicable to all film buffs: “otaku.” Basically, while it does not translate as such, it means someone who stays at home all the time and has no life. Initially, highly negative, otaku has become in recent years more acceptable, with a considerable number of Japanese, particularly those obsessing about anime and manga, self-identifying as otaku. (Because serial killer Tsutomu Kiyazaki had supposedly been influenced by anime and horror films, he was identified in 1990 as “The Otaku Murderer.”)

Perhaps the first individual in the film industry to recognize the existence of film buffs, or at the least the rabidity of fans, was pioneer Carl Laemmle. Prior to his creation of Universal Pictures, Laemmle had founded in 1909 the Independent Moving Picture Company of America or IMP. That same year, he was able to lure leading lady Florence Lawrence away from the American Biograph Company, where she had been recognized by filmgoers as a major star but remained unheralded and unidentified by order of her producers. Lawrence had been billed simply as “The Biograph Girl,” and Laemmle obviously did not wish to promote a rival company by using the same name. Instead, he mounted a publicity campaign claiming that Lawrence had been killed in an accident in St. Louis. Once the story had been picked up by the trade papers, Laemmle denounced it as false, a lie planted in the press by his rivals in an effort to destroy the reputation of his new star. Florence Lawrence was now recognized in her own right and her own name by the fans and the buffs. The cult of personality had been acknowledged by the film community.

Florence Lawrence.

To Carl Laemmle must also go credit for catering to film buffs and film fans with the introduction of the studio tour, which originated at Universal Studios in 1915. Visitors were able to watch filming from the vantage point of bleacher seats built above the dressing room, with the price of admission also including a box lunch. The coming of sound made visiting the sets impractical, and it was discontinued until June 1964, when the current Universal Studio Tours came into being.

They may not have been described as film buffs, but as early as 1911, the trade paper Moving Picture World revealed that there were obsessive fans with many of the same traits found in film buffs of a more recent vintage. These early film buffs could identify the studio responsible for a specific one-reel short subject without viewing the credit title. “The easiest to tell, I think, is the Biograph,” reported the unidentified writer. “Now a Kalem is easy to tell by the outdoor setting.” A French-produced Pathé film was identifiable in comparison with a French-produced film from Gaumont. The same writer, in very film buff-like fashion, complained that Among the Japanese should have been titled Among the Japanese in Chicago or Orientals Tramping around the Studio. He continued, “The number of critical and sharpeyed fans is increasing every day and they [the producers] should know enough to know that pictures of Japan should be taken in Japan.”6

Also in 1911, the Moving Picture World and another trade paper, the New York Dramatic Mirror, began weekly columns in which an in-house authority—Frank Woods, writing as “The Spectator,” at the Mirror—answered questions from filmgoers. The questions generally addressed the identity of an actress or an actor, and both trade papers made it clear that no information on the personal lives of the players would be revealed. As the Moving Picture World made readers prissily aware, “Inquiry as to the private affairs of photoplays will not be answered. This includes the question as to whether or not they are married.”7

As early as the first “Letters and Questions” column in the New York Dramatic Mirror, on July 5, 1911, Frank Woods displayed a certain flippant quality in his replies. When “A Lonesome Old Bachelor” in Philadelphia wrote of Mabel Normand’s being “a lovable, sweet girl, with two great, large eyes and a wonderful personality,” Woods responded, “Really Old Bach [sic] ought to get married. It’s a pity to waste such honest worship on screen girls.”8

Woods is also surprised at the naiveté of his readers. When one in Brooklyn asks as to the identity of “the colored mother” in Vitagraph’s Easter Babies, he answers, “Good gracious! No, she isn’t colored; she’s white.”9

An argument might be made that the appearance of these columns was evidence of the existence of the earliest film buffs, but, of course, truth be told, film buffs would not be asking questions, they would be answering them. It was America’s first fan magazine, Motion Picture Story Magazine, which began actively catering to film buffs, when in July 1912, it announced, “We shall try to reserve a few pages each month for expressions of appreciation from our readers.” The age of the opinionated film buff had arrived, and Motion Picture Story Magazine was quick to acknowledge the worth of the film buff’s opinion when it added that readers were free to send letters, “for which no pay is expected.”10

The earliest known individual who can accurately be described as a film buff is Richard Hoffman, who was born in Manhattan on June 20, 1901, presumably to a fairly affluent, middle-class family. He was an ardent moviegoer, beginning as early as 1913, while living on Staten Island with his mother, Laura, and his stepfather, Basil Scott, and he continued his obsession after a move in the summer of 1914 to the Germantown suburb of Philadelphia, visiting not only theatres in that city but also making regular trips to New York movie houses.

Richard Hoffman was a collector, interested not only in the obvious items, such as fan magazines, easily available to moviegoers, but also trade journals and house organs, and other exhibitor-oriented publications, together with film stills. What sets him apart and definitely “brands” Hoffman as a film buff is the handwritten record that he kept of all the films that he had seen. He divided a loose-leaf binder into sections by distributor, recording the title of the film, the stars, the production company, and the number of reels. He had, as Richard Koszarski has noted, a “methodical approach to his passion.”11 Hoffman’s extant collection ends in January 1917, and no one will ever know if the “passion” continued into his adult life.

Richard Koszarski, who has undertaken extensive research into the collection, concludes that

his collecting had nothing to do with participating in the new medium but instead allowed him to capture some record of the magic he discovered while sitting in those motion picture theaters. Hoffman’s spiritual descendants today are less likely to be found in film schools than at movie “paper shows” and memorabilia auctions—activities that, if my experience is any guide, tend to be completely dominated by males.12

The collection survives, pretty much intact, thanks to a childhood friend, William R. Bogert Jr., who donated it to the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, New York, in 1984, having acquired it after Hoffman’s death, the date of which is unknown, but was apparently a suicide.13 Many film buffs today would surely wish that their collections might survive, and, more importantly, be archived and studied like Richard Hoffman’s.

In 1916, the eminent psychologist Hugo Munsterberg published The Photoplay: A Psychological Study, in which he warned, apropos the motion picture and its audience, of “the trivializing influence of a steady contact with things which are not worth knowing.”14 Munsterberg was undoubtedly unaware of the existence of film buffs, but his comment would seem directed towards them. “An intellectually trained spectator” was what the motion picture needed, not the typical film buff audience.

Also in 1916, a critical year it would appear for recognition of the film buff, Anna Steese Richardson wrote in McClure’s magazine of a disease sweeping the United States and which she identified as “filmitis.” “The germs of infection lurk in every moving picture theatre,” she wrote,15 describing not so much an enthusiasm for the motion picture as an ego crisis affecting many in the audience who felt they could deliver a better performance than those actors on screen and that it was time for them to make the trip to Hollywood and find immediate employment in the industry.

At least one scholar has pointed out that “disease soon became a popular metaphor for fandom, one that was repeated endlessly in the press. Overtaken by the movie bug, fans allegedly lost control of their senses.”16

In September 1926, this mass hysteria culminated in the funeral of Rudolph Valentino, seemingly more popular in death than in life. Merton of the Movies (1924) and Movie Crazy (1932) told in comic form of young men obsessed with an acting career in Hollywood, with the first based on a popular 1922 novel by Harry Leon Wilson, in turn based on an earlier Saturday Evening Post serialization.

Anna Steese Richardson was a former editor of the Woman’s Home Companion, founder of the Better Babies Bureau, and for most of her long and active life heavily involved in women’s issues. She recognized that the primary audience for motion pictures during the industry’s formative years was female, and her article on “filmitis” is obviously addressed to a feminine audience. She was not alone. Fan magazine publishers acknowledged that their readership was female, despite an early attempt to encourage more of a mixed subscription list. In determining an early female enthusiasm for the motion picture, there is a need to recognize that such enthusiasm did not identify itself as manic or buff-ish.

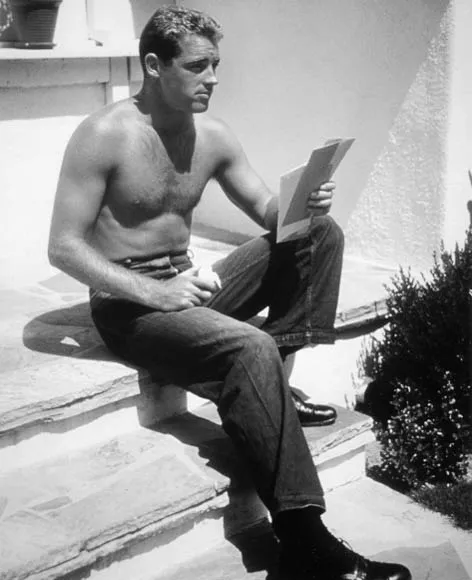

Guy Madison is so anxious to read his fan mail that he does not even have time to put on a shirt.

There can be little argument that autographs by stars for fans have changed drastically in the last one hundred years. In the 1910s, a star might sign a photograph to a fan with the sentiment, “Most Sincerely,” and, generally from a male actor, “Cordially.” The photograph might be a head-and-shoulders shot but it is not unusual for it to be full-body with severe, modest attire. Typical of the formality of the times is a 1917 letter to a fan from George Walsh, which reads in part, “it is gratifying to know that I have staunch friends who express themselves so sincerely as you.”17 Today, someone like Channing Tatum signs a photograph of himself at the minimum stripped to the waist and often further exposed, endorsing it with the words, “All My Love.”

In the past, Anna May Wong, obviously, would sign off with “Orientally Yours.” After publishing his autobiography, Two Reels and a Crank, the cofounder of the Vitagraph Company of America, Albert E. Smith, would sign, “Vitagraphically Yours,” although there is no record that he used that sentiment during the period during which his company was in existence. Alice Lake, a Metro star of the early 1920s, would sign her fan mail with the greeting, “Oceans of Good Cheer from A Lake.” Character actor Hugh Herbert’s catchphrase was “woo hoo,” and he would use that phrase to sign off his fan letters.

In 1916, not surprisingly Bessie Love (born Juanita Horton) signed off a letter to a fan “lovingly,” telling her admirer from Des Moines, Iowa, that “after weeks of hard work on a picture, it is nice to know that it was a success.” For fear that the fan might not realize just how hard it was to act on screen, she continued, “Our work is very trying some times. Emotional acting is not easy.”18

There were stars partial to a particular color for their signature; Ginger Rogers in her prime would always use green ink. In semi-retirement, Rogers became more suspicious of “fans” writing for autographs, suspecting that her signature was being sold (it was), and so she actually kept a card file on those film buffs requesting an autograph, and once a name was in the file, no more s...