This is a test

- 366 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How do the Kara, a small population residing on the eastern bank of the Omo River in southern Ethiopia, manage to be neither annexed nor exterminated by any of the larger groups that surround them? Through the theoretical lens of rhetoric, this book offers an interactionalist analysis of how the Kara negotiate ethnic and non-ethnic differences among themselves, the relations with their various neighbors, and eventually their integration in the Ethiopian state. The model of the "Wheel of Autonomy" captures the interplay of distinction, agency and autonomy that drives these dynamics and offers an innovative perspective on social relations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Wheel of Autonomy by Felix Girke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A Rhetorical Approach to Groups and Ethnicity

During fieldwork in Kara, my main aim was to understand how the people called Kara sustain their political autonomy and their numerically low population in the face of enemies and rivals in the west, friends and relations in the east, and the increasing incorporation into the Ethiopian state with all the pressures this entails. Initially, I did not even realize the significance of the internal divisions within the Kara population, but they quickly rose to prominence in my fieldwork just as much as issues of exchange, intermarriage, and war and peace with external others. Both can be discussed under the heading of ädamo, which in Kara is a protean and very evocative term, and cannot be unambiguously defined. As I use the term ädamo, it stands as a shorthand for the assertion of a fundamental equality among all Kara: ‘Woti paila Karana – we are all Kara’ is sometimes asserted to express how unity derives from equality. But I also call ädamo an ideology, not for entailing a particularly consistent body of precepts and claims, but in the sense of ‘ideas in the service of power’. Specifically, speaking of ädamo as an ideology refers to my observation that for all the invocations of the term, some very real divisions in Kara did not go away. A key element here is the public claim that ethnic differences should be relevant only in terms of ritual practice and should not shape personal interests. To challenge this maxim is to challenge the community. With this link to ritual, ethnicity becomes spiritually loaded and essentialized, appearing inevitable and non-negotiable. As each ethnic category is bound to a specific ritual practice, and as transgression against these proscriptions brings a risk of sickness and doom, it is risky to say the least to not publically display adherence to the ritual code. Such adherence, though, performatively reaffirms the ethnic divisions themselves. At the same time, this second aspect of ädamo allows the ‘true Kara’ – who form the powerful numerical majority – to gloss over their monopoly on making political decisions, especially about the way in which these ethnic differences themselves are organized. Any challenges to this political power of definition, or even acts that hint to expose that claims of ädamo may be duplicitous, are met with reprisals.

I would add a third aspect. These usages of ädamo also indicate the Kara’s awareness that social relations are rhetorically established, sustained and transformed, with the normative corollary that people are responsible for the upkeep of their social world. In the introduction I have outlined how I found such ädamo in ontologically uncertain but interactionally satisfying ‘as if’ role behaviour. Beyond individual actors, this is equally true even of group relations across ethnic boundaries, and I will go on to explore how such relations are verbalized, conceptualized and practised both within the Kara population and between it and outside groups.

The thrust, then, is two-pronged. On the methodological level, I present a toolkit that is useful both for modelling classifications and for tracing the rhetorical ways in which these systems of classification are enacted, modified or denied. On the ethnographic level, I describe interaction, trace how groups and social categories work in and around Kara, and observe how people struggle over definitions of the situation, bringing to bear ideological constructs such as ädamo. My rhetorical approach and the description are co-emergent, as the description substantiates the methodological reflections, while the vocabulary of persuasion gives shape to the ethnographic material.

To make my case, I discuss some more general methodological points under the headings of ‘The Wheel of Autonomy’, ‘Classification and Social Life’ and ‘Defining Situations through Rhetoric’ below. A summary brings together the main theoretical considerations, as they will come to be applied throughout the later chapters of this book.

In anthropological terms, this book is both about social classification and political practice, and rhetoric is the way in which these two fields of interest are linked (compare Brubaker et al. 2004: 36f). An understanding of these links is essential for an understanding of either subject. Prime among these links are what has been called ‘languages of claims’ (see Bailey 1969: 108). By this I refer to culturally grounded and rhetorical assertions about an ‘ought’ or an ‘is’. There are usually several ‘languages of claims’ available that will be in competition with one another. In order to reach their goals, actors attempt to persuade others of their version of things. Such versions are hardly ever single, unrelated notions or claims. Rather, they relate back to larger associative sets of classification, which give depth to argument, and suggest implications and entailments. In interaction, then, people seek agreement on one out of many potentially applicable classificatory systems so as to enable joint action. I work from the basis that such agreement is problematic and that social struggle is precisely about competitive attempts to make specific frames count. To be successful in this has direct effects on the interaction, on the actors’ positions, as well as on the frame that has been applied. What ‘counts’, however, is not as a rule decided by the contestants alone: studies of interaction are improved by the understanding that any dyad of actors is complemented by witnesses, by an (at the very least imaginary) third party. With a third party as an audience, interaction becomes performative (see Carlson 1996: 5), because it is inevitably scrutinized, processed and interpreted by present observers. It is such an audience’s reaction that gives a culturally valid interpretation to moves and countermoves in people’s attempts to apply their preferred classificatory system. Relevant ‘meaning’ is not hidden within an utterance that we have to decode. Instead, it emerges out of the joint interpretation of the situation by all social persons present. Actors do well to take this condition into account in the way they behave, no matter how genuinely affective or coldly calculating they proceed. It follows from this that I rarely aim at unravelling the ‘real’ reasons for people’s choices, but that I am instead interested in the culturally valid ways in which other people make sense of what is happening. Any analysis of someone’s behaviour should be directed at how a given audience reacts to actions and utterances, and should not attempt to discern what the speaker ‘really meant’. This is neither possible nor particularly interesting. As F.G. Bailey already cogently argued:

The best we can do is discover the motivations which are explicitly current in and explicitly acceptable at various levels in that particular culture, and how, when they conflict, they are measured against one another. (1973: 325)

But this somewhat deprecatingly issued ‘the best we can do’ is in fact very good indeed – Bailey’s statement encapsulates for me what cultural anthropology is largely about. To forego ‘mind-reading’ lets the anthropologist join other local actors, who are themselves constantly busy inferring meaning and attributing intention to action. This in principle ethnomethodological stance is especially well formulated by Jonathan Potter:

The argument is not that social researchers should interpret people’s discourse in terms of their individual or group interests. There are all sorts of difficulties with such an analytic programme, not least of which is that it is very difficult to identify interests in a way that is separable from the sorts of occasioned interest attribution that participants use when in debate with one another … The argument here is that people treat one another in this way. They treat reports and descriptions as if they come from groups and individuals with interests, desires, ambitions and stake in some versions of what the world is like. Interests are a participant’s concern, and that is how they can enter analysis. (2004: 110, emphasis in original)

Of course, this is also the way in which ‘participants’ constitute (imagine?) themselves in the first place. The argument is even stronger when we take into account that in many cultures it is well recognized that ‘authentic motivations’ are by and large inaccessible (see Herzfeld 1984).

This book, then, translates observed Kara practices on the basis of local exegesis, the anthropologist’s contextual knowledge, and supplemental data. Ädamo appears in this translation as a specific ideology, as it is used by actors to remove the realities of power from open debate, just as ädamo can plausibly be said to be the very manifestation of power. Ädamo is a major argument in the culturally specific language of claims through which the Kara negotiate their dynamic social relations. My approach is based on the recognition of the mutual constitution and co-emergence of social interaction and cultural systems of classification, and grounds them by attending to the internal tensions that arise in the everyday life of a face-to-face community.

Victor Turner has warned interactionalist anthropology not to forget that people are ready to die for ‘values that oppose their interests and promote interests that oppose their values’ (1974: 140). Exploring the rhetorical aspects of interaction as people reinforce or challenge each other’s claims is a way to work out how these tensions come about.

The Wheel of Autonomy

In order to interact meaningfully, actors need to be experienced as different. A ‘relation’, logically, can only exist between at least two elements conceived of as separate in some way – not necessarily in all ways. As Todorov maintains, it is also not necessary that the existence of the individual precedes the relation:

There is no point in asking oneself, in Hobbesian fashion: Why do men choose to live in society? or like Schopenhauer: Where does the need for society come from? because mankind never makes this passage into communal life. The relationship precedes the isolated element. People do not live in society because of self-interest or because of virtue or because of the strength of other reasons, no matter what they might be. They do so because for them no other form of life is possible. (2001: 4f)

On the ground, what may constitute an actor is not a given, as conceptions of ‘the individual’ may vary culturally. Also, legitimacy of action may be denied to certain social categories, and people will always encounter constraints in favouring or even expressing their individual interests at the expense of the group. Recognizing these tensions, I want to preface my elaboration of the question of agency, autonomy and distinction with Gluckman’s acknowledgement that even numerically small communities are often ‘elaborately divided and cross-divided by customary allegiances’ (1973: 1f). Even the Kara population’s absolute smallness, and the predominance of multiplex relations and shared knowledge among them, then, does not preclude relative dividedness.

Drawing on a ‘wrongly neglected’ line of sociological argument, found in the work of Freud, Simmel, Bateson and literary critic Girard, the Melanesianist scholar Simon Harrison (2002: 228) has called attention to processes of differentiation in the face of objective similarity. He suggests that it is the very closeness and the mutual resemblance of individuals (and groups) that can cause conflictual acts of differentiation:

A problem people seem to face in small, close-knit social worlds is that they can sometimes appear to themselves to resemble each other a little too much. They may be conscious of sharing many deeply held values, goals, and beliefs. But they may not – or some of them may not – always wish to share them. (2002: 223)

I pick up from here. What is it, then, that drives both groups and individuals into differentiation? Numerous answers have been given to this – be it ‘face wants’ as suggested by psycholinguistics (Brown and Levinson 1987; Strecker 1988, 2006b), the fear of an evil twin or doppelganger (see Harrison 2002: 214), ‘identity space’ (Friedman 1992: 837), the triangular structure of ‘mimetic desire’ (Girard 1977; Harrison 2006: 2ff) or Simmel’s ‘intellectual private property’ (1950: 322). I understand these concepts as all referring to similar empirical phenomena: people who share much make much ado over some seemingly minor differences. Familiar examples include regionalism, gang colours, campanilismo, youth fashion and innumerable other examples (see Harrison 2006: 6).

Much work in social science has been devoted to this general issue. I want to specifically highlight the work that revolves around the ‘narcissism of minor differences’, a phrase coined by Freud. Besides Simon Harrison, Anton Blok is the most prominent proponent of this position.1 A fitting piece of imagery was first supplied by Arthur Schopenhauer in his ‘Die Parabel von den Stachelschweinen’ and was then picked up by various other authors (see Blok 1998: 34f): porcupines seeking warmth want to huddle together, yet find that they sting one another. They end up maintaining what Harrison calls a ‘modicum of mutual distance’ (2006: 2). In other words, closeness comes at a cost – the cost of unimpeded autonomy. In an allegory by Fredrik Barth, the logical consequence is illustrated: two neighbours can precisely interact and converse ‘in a more carefree and relaxed way’ when they have erected a nice straight fence between their two plots. Without a fence, ‘entanglements’ loom (2000: 28).2 Predictable relationships, nonpredatory and mutual, then, require the creation of distance and difference – if all were equal, ordered relations would be logically impossible.

Figure 1.1 Teenage girls grinding sorghum (June 2006). Photograph by Felix Girke.

This line of argument understands that (felt) autonomy is a goal in itself for social actors. However, such autonomy is not of the hermetic kind and fully self-sufficient; on the contrary, it emerges from a public recognition of one’s legitimate distinctiveness. Having achieved that, the actor can proceed to engage in interaction on their own terms.

As both Harrison and Blok have developed this approach, it applies to groups just as much as to individuals, and aligns with Barthian studies of ethnicity: ‘From this perspective, boundary processes are fundamental, irreducible social phenomena. Social groups and categories, in contrast, are merely their epiphenomena. They are just the visible effects of successful acts of differentiation’ (Harrison 2006: 8). Accordingly, the position of any given porcupine can only be appreciated if one also perceives the position of the other porcupines and how long their respective quills are.

In symbolic interaction, differentiation often comes to be focused on iconic objects, places or practices. Any encroachment of an other upon one of these diacritical sites can occasion acts of division, even before it ever comes to a material struggle over resources: ‘According to this view, an identity is never in some sense self-sufficient, but is always linked to an other – real or imagined, overt or covert – against which it is defined’ (Harrison 2006: 38). To stick with the prickly metaphor, this means that porcupines will have very different space demands vis-à-vis birds in the sky, wandering human beings, ants on the ground or their own species. A critical category marker for the relation to one other can be meaningless in a slightly different context, and differences that need to be maintained in one relation can be surrendered in another. This corresponds to the by now classic understanding in anthropology that while distinction is always involved in boundary processes, it is not always the same distinction that is put to work by the same actors (Barth 1969, 2000: 21; Wimmer 2008). So for each kind of actor, group or individual, one needs to find those significant others from which they must at all times be distinct. A self is a self in a community of selves, and an empire is only an empire if surrounded by barbarians (or, eventually, other empires).

We do not choose all these significant others for ourselves. As social beings, we are already born into a world of categories, distinctions and relations. In order to navigate our lives, we ‘appeal to identities to make sense of [our] relations’ (Otto and Driessen 2000: 11; see also Eriksen 2001: 86). But what happens when relations between distinct beings change – for example, when people engage in mimesis, or its obverse, when people problematize their similarities? This is the problem of the ‘minor differences’, and Blok credits Pierre Bourdieu with having ‘re-opened the debate’ (2000: 34) with his oft-quoted phrase that: ‘Social identity lies in difference, and difference is asserted against what is closest, which represents the greatest threat’ (Bourdieu 1984: 479). So it is not the minor differences that are the problem, but the numerous similarities; the minor differences are where distinction can be found and be blown up beyond all proportion. In Girard’s terms: ‘It is not the differences but the loss of them that gives rise to violence and chaos’ (1977, quoted in Blok 2000: 27). As Harrison well realizes, the minor differences are highly contingent, and there is no necessity that the shared attributes might not historically ‘have been used to foster some form of common identity or cohesion’ (2002: 227). But when push comes to shove, people ‘protect their idiosyncrasies jealously’ (2002: 212).

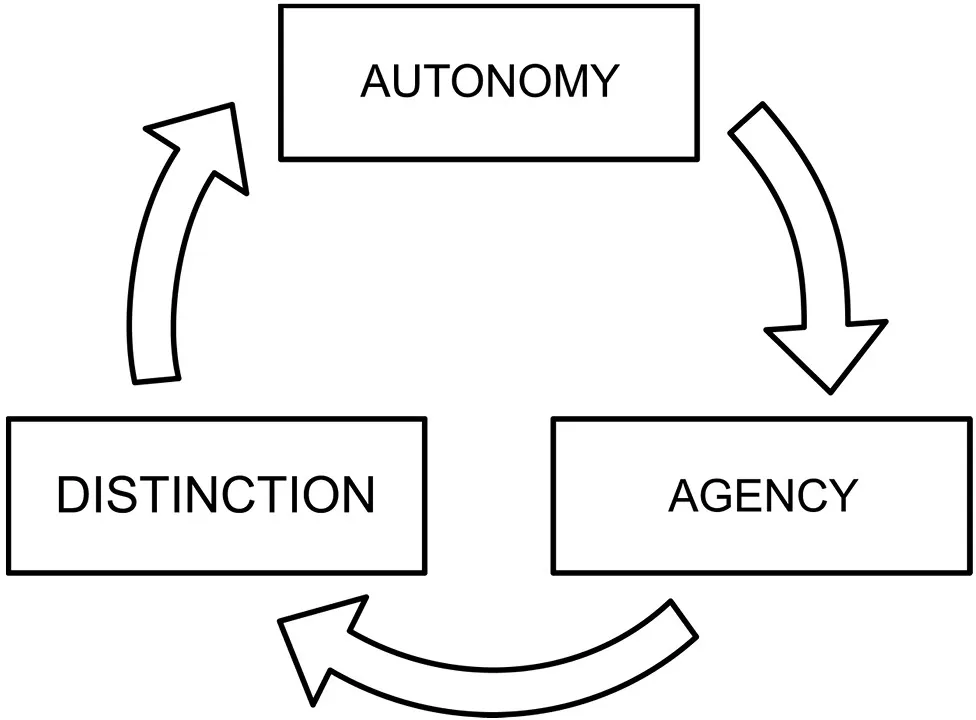

To visualize what is going on when actors assert themselves and demand recognition, I have devised a circular model for the social process of differentiation, called the Wheel of Autonomy. The claim is that this model can in principle be applied to all social action. It operates like this: distinction is a logical prerequisite to autonomy. Autonomy affords agency. The exertion of agency effects distinction. These relationships are fairly intuitive even from the common use of these terms. I see all three to be so essentially connected as to mutually define each other. But why is it called the Wheel of ‘Autonomy’ if the three elements are seen as inseparable? To prioritize autonomy the way I do now is not wholly arbitrary: following the academic line of discussion traced above, I take the existential need for autonomy (as endorsed by the listed concepts from Levinson and Brown to Simmel) as the starting point for the analysis of how actors stay identical with themselves.

Figure 1.2 The Wheel of Autonomy. Diagram by Felix Girke.

But what can such a perpetual motion machine tell us? Does the process not need to start somewhere? It does, but it does not – we are all already born into a world of categories and relations. Watching a child grow up and struggle with the conflicting desires of autonomy and intimacy is illustrative – or does already the first kick of the foetus set the wheel in motion? Circularity is the very nature of the processes under consideration, which the Wheel of Autonomy models. Starting from autonomy, agency (as the capacity to act) comes to be linked to power and status. Harrison does not quite go far enough when he states (following Simmel) that ‘[o]ne shows greater respect and deference to someone by “keeping one’s distance”, allowing that person a larger sphere of psychological privacy’ (2002: 216, also 218). I would add that in social action, the relation can be reversed: by successfully demanding greater identity space (i.e. autonomy), we gain in power and status. Agency, then, is our potential to act as a distinct, autonomous actor vis-à-vis other actors. Thus, the Wheel could also be pictured as a gear, constantly locking teeth with other people’s Wheels, and thus influencing the ways in which they can assert their autonomy, distinction and agency. Since all three sections of the Wheel are inherently social and intersubjective, there is a corollary to the model: while ‘zero degree agency’ does not seem not a helpful concept, actors will be able to ‘opt out’ in certain contexts, when they stop to publicly assert their agency by continually jockeying with the other porcupines. They can also be denied autonomy and they can be p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction. How Do They Do It?

- Chapter 1. A Rhetorical Approach to Groups and Ethnicity

- Chapter 2. Categories of Being Kara

- Chapter 3. Ethnicity within Kara: The Demotion of the Bogudo

- Chapter 4. The Moguji: All That Is Not Kara

- Chapter 5. The Schism and Other Predicaments of the Moguji

- Chapter 6. The Regional Other in the Cultural Neighbourhood

- Chapter 7. South Omo in Kara Terms

- Chapter 8. The Cleverness of the Kara

- Chapter 9. Seeing Like a Tribe

- Conclusion

- Glossary of Non-English Terms

- Glossary of Places and People

- References

- Index