This is a test

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

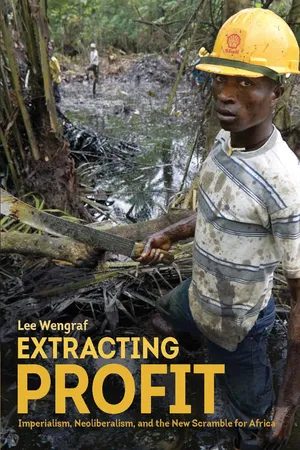

Extracting profit explains why Africa, in the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century, has undergone an economic boom. This period of "Africa rising" did not lead to the creation of jobs but has instead fueled the growth of the extraction of natural resources and an increasingly-wealthy African ruling class.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Extracting Profit by Lee Wengraf in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Colonialism & Post-Colonialism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction and Overview

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the turning of Africa into a commercial warren for the hunting of black skins signaled the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief moments of primitive accumulation. On their heels treads the commercial war of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre.

—Karl Marx, Capital, Volume One1

Trade by force dating back centuries; slavery that uprooted and dispossessed around 12 million Africans; precious metals spirited away; the 19th century emergence of racist ideologies to justify colonialism; the … carve-up of Africa into dysfunctional territories in a Berlin negotiating room; the construction of settler-colonial and extractive-colonial systems—of which apartheid, the German occupation of Namibia, the Portuguese colonies and King Leopold’s Belgian Congo were perhaps only the most blatant; … Cold War battlegrounds—proxies for US/USSR conflicts—filled with millions of corpses; other wars catalyzed by mineral searches and offshoot violence such as witnessed in blood diamonds and coltan; poacher-stripped swathes of East, Central and Southern Africa; … societies used as guinea pigs in the latest corporate pharmaceutical test; and the list could continue.

—Patrick Bond, Looting Africa: The Economics of Exploitation2

In July 2002, 600 Itsekiri women occupied Chevron’s Escravos oil terminal in Nigeria’s Delta State. For ten days, the occupiers held the extraction site, demanding the oil corporation make good on promises for ecological and economic development: jobs, electrification of villages, and an environmental clean-up of polluted local fishing and farming communities. While billions in revenue accrued to the oil multinationals, Nigerians in oil-producing states lived under horrific conditions of oil spills and gas flares, without the most fundamental basic services.

On the heels of the Escravos action, Ijaw women took over four pipelines feeding into the terminal. Operations ground to a halt. “The rivers they are polluting is our life and death,” declared Ilaje protester Bmipe Ebi. “We depend on it for everything…. When this situation is unbearable, we decided to come together to protest…. Our common enemies are the oil companies and their backers.”3

It was a summer of struggle in the Niger Delta: thousands of women in total took over eight oil facilities owned by Chevron/Texaco and Shell Petroleum. Delta region advocate and author Sokari Ekine describes the unprecedented mobilizations:

One of the strategies used by both the multinational oil companies and successive Nigerian governments has been to deliberately exploit existing tensions between the various ethnic nationalities in the region and to encourage antagonisms between youth and women, elders and youth, and elders and women in towns and villages. Therefore, the importance of the solidarity between women in this instance is indeed major.4

Protests and occupations by women from Delta communities have continued to the present day. Likewise, Chevron and its long-standing record of devastation, exploitation, and betrayal remain in the sight lines of communities of resistance: in August 2016, the Escravos site was once again targeted by activists who launched a sit-in at the company gates, demanding promised jobs. They were met by Nigerian Army troops called out to disperse them.5

The deeper problems of conditions in the region are not so easily dispersed. From Escravos and beyond, the Niger Delta can be viewed as embodying the contradictions of extraction on the continent. Many African economies rely heavily on natural resources and raw materials—with a relatively new rush by multinationals for oil, gold, platinum, industrial metals, and more, producing in the twenty-first century levels of economic growth and investment not seen on the continent in decades. Yet this exploitation has enriched only a tiny handful: investors, African elites, and international capital. The recent “scramble for Africa”—its class contradictions, environmental devastation, and the resistance it has produced—is only the latest chapter.

The scramble for Africa’s wealth has a long and sordid history. From the era of slavery through colonialism and post-independence, the exploitation of the continent by the West has been accompanied by economic stagnation, poverty, war, and disease for millions. As Walter Rodney famously described in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972), from its earliest days, the slave trade, colonial “encounter,” industrial boom, and the rise of imperialism have combined to produce exploitation and inequality on a mass scale. “The operation of the imperialist system,” Rodney wrote, “bears major responsibility for African economic retardation by draining African wealth and by making it impossible to develop more rapidly the resources of the continent.”6

This history is by no means a distant chapter in the relationship between Africa and the West. The exploitation of Africa has continued into the recent neoliberal era. By neoliberalism, I mean the period of global capitalist restructuring launched by Western ruling classes as an attempt to restore corporate profitability following the economic crisis of the 1970s. Beginning under US President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, neoliberalism is marked by dismantling barriers to corporate globalization and accumulation, such as imposing free-trade agreements, austerity, and attacks on unions. Likewise, the current phase of imperialism has its roots in past eras; by imperialism, I mean the tendency for economic competition between nations to produce conflicts across borders—both economically, such as trade wars, as well as outright military conflict. Yet while the influences of this history continue to be felt on “Africa’s economic retardation,” as Rodney put it, the past likewise does not merely repeat itself. The current phase of imperialism—with critical roles played by both China and the United States—has a different dynamic than the colonial, post-independence, or Cold War eras.

The historical roots of the current period will be discussed in the pages ahead. To summarize briefly here, the division of Africa’s “spoils” by colonial powers at the Berlin conference of 1885 formalized carving up virtually the entire continent. Whether through direct or indirect rule, African economies and societies were transformed to expand profits and markets for Western capitalism. These chains were finally broken three-quarters of a century after Berlin: the postwar struggles for independence saw European powers driven from the continent in revolutionary upheavals beginning in the 1950s and extending up until the 1970s. The promise of these movements and the birth of new nations in Africa brought a new generation of African rulers to power at the hands of mass movements of African workers, peasants, and students, who inspired and contributed to movements for liberation across the globe.7

In the immediate post-independence era, African states became weak pawns in the world economy—subject to Cold War rivalries, their path to development largely blocked by a debilitating colonial past and an unfortunate set of largely external economic circumstances. The era of neoliberalism was birthed in the global recession of the 1970s, when many so-called “Third World”8 nations, including those in Africa, were compelled to turn to loans from Western financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. An onerous debt regime forced many nations to pay more in interest on debts to the World Bank and the IMF than on health care, education, infrastructure, and other vital services combined. Debt repayment was accompanied by the imposition of structural adjustment “reforms”: privatization, deregulation, and the removal of trade barriers to foreign investors. Harsh austerity and deindustrialization produced a sharp decline in living conditions, while new nations were saddled with insurmountable levels of debt.

Much has been written about the past decade’s so-called boom in Africa—one characterized by high primary commodity prices that have driven unprecedented growth rates in the new millennium, even (relatively speaking) during the 2008–2009 recession. Today, Western multinationals and African elites have accumulated vast profits from their investments. The value of fuel and mineral exports from Africa has reached into the hundreds of billions, exceeding the aid that flows into the continent. Surplus appropriation—that is, the value accruing to capitalists via the exploitation of labor and natural resources—reverberates across Africa, producing huge wealth while millions live in the worst poverty found on earth. The business press has championed the most recent “scramble,” from oil and mining to massive land grabs for agribusiness development.

Yet there is nothing new about a scramble for Africa’s natural resources. This twenty-first-century boom has appropriately been described as a “new scramble” for Africa in the media and academic accounts alike. This reference evokes the remarkably similar nineteenth-century scramble for Africa—typically understood as the period from the partitioning at Berlin to World War I—and the colonial rush at breakneck speed to claim the continent’s raw materials. The so-called new scramble, over a century on, is similarly an era of competition and a drive to profit from the exploitation of Africa’s valuable oil and minerals.

Case studies such as Where Vultures Feast: Shell, Human Rights and Oil (2003) by Ike Okonta and Oronto Douglas have documented the current plunder. Academic studies such as Padraig Carmody’s The New Scramble for Africa (2011) and Roger Southall and Henning Melber’s A New Scramble for Africa? Imperialism, Investment and Development (2009) provide important analyses of the resource issues in Africa today. Geographer Michael Watts has produced numerous invaluable works on the long history and dirty politics of Africa’s resource wars and today’s “oil insurgency,” along with a damning indictment of flawed notions of a “resource curse.” Journalistic accounts such as those from John Ghazvinian (2007), Nicholas Shaxson (2008), Celeste Hicks (2015), and Tom Burgis (2015) have explored similar terrain, with first-hand reporting from the frontlines of the new economy. Finally, the environmental advocacy and writings of activists like Nnimmo Bassey—as in his brilliant To Cook a Continent: Destructive Extraction and the Climate Crisis in Africa (2012)—elaborate on the challenges posed for the left in confronting multinational-driven devastation. Meanwhile, investigators such as Khadija Sharife and the Tax Justice Network Africa have shone a much-needed spotlight on the machinations and illegal practices that have facilitated the accumulation of profits in the extractive industries to soaring new heights.

China’s key role in Africa has evolved rapidly since the turn of the millennium. The boom in China’s economy has spurred a drive for new sources of energy as well as new markets, and a host of African nations have emerged as allies. Now Africa’s largest trading partner, China has a footprint that can be found across large swaths of the continent. Important reports such as African Perspectives on China in Africa (Fahamu Books and Pambazuka Press, 2007) anticipated the growing closeness between the Chinese government and various African nations, including the major oil producers on the continent, such as Angola, and those with large deposits of valuable minerals, such as Zambia. More recent accounts, such as Howard French’s China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa (2014),9 along with writings by Deborah Brautigam,10 have painted the picture of the transformed relationship between these regions and the dramatic changes for ordinary Africans with new Chinese immigration and investment.

China’s expanded presence in Africa highlights its global rivalry with the United States and has accentuated imperial competition between the major powers. As the US Department of Defense states in a critical strategy document:

In order to credibly deter potential adversaries and to prevent them from achieving their objectives, the United States must maintain its ability to project power in areas in which our access and freedom to operate are challenged…. States such as China … will continue to pursue asymmetric means to counter our power projection capabilities.11

Twenty-first century wars and military expansion thus characterize a new imperial phase of economic volatility and political instability. Heightened competition—with China, above all, but also with the European Union and “emerging” nations—over control of resources, especially oil, along with the drive for “energy security,” have produced a wider global militarization that now encompasses sub-Saharan Africa. The United States has approached this environment of heightened competition with an eye toward protecting its strategic interests, deploying military might alongside aggressive economic and trade policy to do so. Former US President George W. Bush created the African military command known as AFRICOM in 2007 as means of containing its competitors and projecting US power on the continent (see chapter 7 for more on this period).

A decade later, military “involvement” on the continent shows no signs of abating. The Obama administration widened these activities to include new military outposts, drone warfare, logistics infrastructure, and a heightened “war on terror.” Intrepid investigative reporting by US journalists Nick Turse, Jeremy Scahill, and the Washington Post’s Craig Whitlock have made key contributions to our understanding of a vastly more militarized continent in the age of AFRICOM. As Turse has written, the US military now has a presence in virtually every country on the continent.12 By the midpoint of the 2010s, a sharp downward turn of the Chinese economy, along with a crash in commodities prices, has once again subjected African—and global—economies to the “boom and bust” vacillations of capitalism. Today’s intensified militarism in Africa only raises the prospects for economic crises to take a military form, where capitalists increasingly turn to the armed power of “their” states to secure access to markets, territories, and control of natural resources, especially oil. The deep crisis in the neighboring Middle East poses dangers for imperial powers with the spread of that instability into Africa. In addition, that increased instability undermines the geostrategic “usefulness” of the African continent for the United States, in particular to project its power into the Middle East. All told, imperial expansion and its contradictions have made Africa—and the world—a vastly more dangerous place.

Finally, militarization, neoliberal structural adjustment, and the boom in investment and extraction—accompanied by an increase in productivity and exploitation—have been met by resistance across the continent. From the explosive strikes and protests against debt crisis created by the IMF and World Bank in the 1980s to pro-democracy struggles and mobilizations against cuts to social services in urban areas and land grabs in the rural countryside, the organizing of workers and ordinary people across the continent has indicated that the new African boom will not unfold without challenges from below. As Firoze Manji and Sokari Ekine describe in African Awakening: The Emerging Revolutions (2011), the processes of rebellion and revolution in North Africa and the Middle East during the Arab Spring were by no means separate from the dynamics of struggle throughout the rest of Africa, and in fact were accompanied by struggle throughout the continent. And as Leo Zeilig, Trevor Ngwame, Peter Dwyer, and others have described, the long history of trade union struggle and social movements have produced critical lessons and important continuities for resistance today.

Myths and Realities of African “Underdevelopment”

Running through the history of African exploitation, from the age of slavery onward, are a host of racist theoretical and ideological explanations and justifications for the continent’s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview

- PART ONE

- PART TWO

- Selected Bibliography

- Notes

- Index

- Back Cover