This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

> Richard Register is highly regarded internationally for his ecological city work through Ecocity Builders > The first edition of this book was published by Berkeley Hills Press in 2002 and received little distribution, garnering about 6,000 copies sold > This second edition includes three times as many illustrations as the first edition, all by the author

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access EcoCities by Richard Register in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & LandscapingCHAPTER 1

As We Build, So Shall We Live

AS WE BUILD, SO SHALL WE LIVE. The city, town, or village — this arrangement of buildings, streets, vehicles, and planned landscapes that serves as home — organizes our resources and technologies and shapes our forms of expression. It is the key to a healthy evolution of our species and will determine the fate of countless other species as well. The city, in fact, is the cornerstone of the civilization that currently embraces the entire planet. Insofar as our civilization has gone awry, especially with regard to its impacts on the environment, a very large share of the problem can be traced to its physical foundations. Given the crisis state of life systems on Earth — the collapse of whole habitats and the increasing rates of extinction of species — it follows that cities need to be radically reshaped. Cities need to be rebuilt from their roots in the soil, from their concrete and steel foundations on up. They need to be reorganized and rebuilt upon ecological principles.

Yet most people believe instead that fine-tuning the same old civilization will be enough, that there is no real need for fundamental change in the way we build and live. But simply failing to notice the crisis in the built environment won’t make it go away. Only rebuilding will. Building the ecocity will create a new cultural and economic life in which we can tackle the problems of healthy evolution rather than fighting a rearguard action aimed at repairing the damage. While it probably won’t rid the world of greed, ethnocentrism, and violence, building a nonviolent city that respects other life forms and celebrates human creativity and diversity is consistent with solving those problems.

Cities need to be radically reshaped. Cities need to be rebuilt from their roots in the soil, from their concrete and steel foundations on up. They need to be reorganized and rebuilt upon ecological principles.

dp n="33" folio="6" ?

What we build creates possibilities for, and limits on, the way we live. What we build teaches those who live in the city, town, or village about our values and concerns. It says, “This is the way it should be,” or at least, “This is the best we could do.” The edifice edifies. Children in today’s typical car-dominated cities learn that cars are valued so highly that it is worth risking human life and enduring high costs and serious pollution to make way for them. They also learn that people don’t care much for public life or nature. In Berkeley, California, where I lived for 30 years until recently, there are no public plazas or pedestrian streets, though you can be sure there are thousands of parking places and cars on every street. Creeks are buried for miles, and the ridgelines from which we could once enjoy the sunset and a view of San Francisco Bay are increasingly being filled with private houses that banish public access. In ways like this each city tends to reproduce in its children the values embodied in its form and expressed in its functioning.

Each city tends to reproduce in its children the values embodied in its form and expressed in its functioning.

More to the point, if our cities are built for cars, one sixth of us will find jobs in that industry and its support systems, and another sixth will be building and fixing the buildings and infrastructure that go along with the layout automobiles require. But if we build the ecocity, large numbers of people will find jobs involving its building and operation. By shifting steadily toward an ecocity infrastructure we could soon train people to be streetcar and bicycle builders and mechanics, organic gardeners, restorationists, naturalists, “green” designers and builders, and pedal-powered delivery people, all with a minimal impact on nature. As we build, so shall we live.

Even more, as we live, so shall we become. And not only in attitudes, skills, and habits, but also, eventually, in physical form. As Americans spend more and more time sitting motionless before television and computer screens and in ever fatter SUVs, they are becoming increasingly overweight and unhealthy. Another way of looking at this is to see that we build environments that help build us. We are indirectly self-designing in a very significant way, turning ourselves into a species that reinforces its own design by building its environment in particular ways. In ecology and evolutionary biology, we have learned that species shape one another physically and behaviorally. Pollinating insects and birds adjusted their proboscises and beaks to the task, and flowers shaped themselves to cooperate. The birds were fed. The flowers were pollinated. Some birds’ nests have evolved over thousands of years, affecting the birds’ behavior and even body shape. All creatures respond to and alter their habitats, climate, and even atmospheric and soil chemistry, thus altering themselves over the years. If we want to live an ecologically healthy and responsible life, we need to build so that we can lead such a life.

dp n="34" folio="7" ?What We Seem to Be Building

Since 1991 I have traveled several times to all the continents but Antarctica talking about ecocities. I am one of a small number of people on this loosely linked lecture circuit who are thinking about redesigning and building whole cities on ecological principles. My experience suggests that a significant and growing number of people around the world are beginning to take a strong interest in urban form and related dysfunction and in the ecologically healthy alternatives that ecocities offer. Cities such as Vancouver, British Columbia; Portland, Oregon; Curitiba, Brazil; and Waitakere, New Zealand, are making ecological progress on a number of fronts, and the international ecovillage movement is steadily growing. We are seeing good work, and that is significant and heartening. But society is still moving overwhelmingly in the opposite direction.

For my 30 years in Berkeley, for example, I had been trying to help reshape the city. With others I cofounded two nonprofit organizations — Urban Ecology in 1975 and Ecocity Builders in 1992 — and these groups have managed to have portions of creeks that had been buried for decades opened, to have a street redesigned as a “Slow Street,” to have a bus line established, to have an ordinance written making attached solar greenhouses legal in front yards, to build a few of these greenhouses, to plant and harvest street fruit trees, to have energy-saving ordinances developed, to delay freeway construction, to tear up parking lots to plant gardens and urban orchards, and to affect the course of particular development projects by pointing out their impacts on the city’s ecological health. These and other projects have not only created physical features and functions and established laws, but stimulated discussion of these issues, as well.

It has gradually become clear, however, that few people notice. New one-story buildings are being built in the downtown, where taller buildings would place transit and passengers in mutually supportive proximity. Transit service itself is being cut and fares are rising. The neighborhood around one of the major transit stations has been rezoned for reduced development, when a higher-density “transit village” would have helped housing, transit, energy conservation, pollution abatement, and the economy. Large freeway-oriented projects and big parking lots have been built as an outcome of a planning process with considerable public support and input — many people wanted it that way. These projects and parking lots, not only in Berkeley but all over the region, encouraged the widening of Interstate 80 from eight to ten crowded lanes. The University of California built several very large buildings and parking lots in that period with little regard to its surrounding urban and natural environment.

At the national level, despite ever more intense verbal attacks on sprawl, the big news early in the first decade of the third millennium is bigger sport utility vehicles and capitulations to ever more highways, parking lots, bridges, and other car infrastructure. For example, in 1960 one-third of the citizens of the United States lived in cities, one-third in suburbs, and one-third in rural locations. By 1990, well over half lived in suburbs. Between 1970 and 1990, the population of California increased approximately 40 percent while the land area of cities and suburbs went up 100 percent. Between those years the country witnessed what has sometimes been called “the second suburbanization of America,” in which, instead of commuting daily from suburb to city center, tens of millions of people began traveling from suburban house to suburban workplace. It’s not uncommon for spouses to work thirty to sixty miles apart while their children attend school at the third corner of a geographical triangle, encompassing hundreds of square miles.

Since 1970, giant suburban developments have popped up on a scale and in numbers barely imaginable before. Industrial and “back office” business parks have appeared on farm, range, forest, and filled marsh lands miles from any other development. These office and commercial zones are surrounded by acres of land converted to dead-level asphalt and concrete slabs, sweltering in the summer, pouring car-contaminated waters into the creeks, rivers, and bays when it rains, and draining rubber dust and oily, salty, sooty snowmelt in winter. Privately owned malls, accessible virtually only by car, have largely replaced town and neighborhood centers, shifting social spaces from public to private control. New communities of hundreds, even thousands of families are hiding behind walls and guard posts, “forting up,” in the words of the real estate pages, abandoning the inner cities and physically distancing themselves from social accountability. They are attaining this social isolation through the physical isolation of sprawl, cars, asphalt, gasoline, and concrete block walls eight to eighteen feet high. Only expected guests and the electromagnetic waves and wires of radio, television, computers, and telephones dare enter.

In 1972, before the oil embargo and the subsequent energy crisis, cars consumed on the average about 30 percent more energy per mile than they did 15 years later. About a third of the United States’ oil was coming from the Middle East. By 1992, after the new wave of suburbanization, the United States was getting approximately 60 percent of its oil from the Middle East. The less fuel it takes to drive about and the cheaper per mile it is, the farther people are willing to drive. The better the mileage, the more the suburbs sprawl out over vast landscapes, the more demand there is for cars and freeways, the more cars are needed to service expanding suburbia, and, ultimately and ironically, the more gasoline is needed. Thus the energy-efficient car creates the energy-inefficient city, the “better” car the worse the city. The car is part of a whole system of complex, necessarily interconnecting parts existing in an interdependent relationship with the total environment it helps create.

The bigger picture — represented by the total commuting time for large populations, the world use of fossil fuels, ocean tanker oil spills, wars for oil in the Middle East, the waste of investment capital in building infrastructure that will go on damaging the world for many decades, and so on — is far from encouraging. China started closing Beijing’s streets to bicycles to make way for cars in 1998, and it is currently engaged in a massive highway-building program. It plans enormous shifts of population from rural areas and farming to cities and manufacturing and business, and shifts from rail, bicycle, and pedestrian cities to cities for motor vehicles on rubber tires — a colossal transformation in the wrong direction. In Brazil, Turkey, India, Africa, and Australia, large highway projects are being built as they all emulate America’s destructive example. People in these places say quite directly and from their point of view completely reasonably, “You Americans have cars — who are you to say we shouldn’t? Now it’s our turn.”

Good place for a freeway. This drawing I took as something of a joke until ten years later, when I learned the freeway on the far side of the Danube from downtown Vienna was buried for more than two miles — with above - ground air ventilation boxes of identical design.

dp n="37" folio="10" ?Getting down to Basics

To move forward from this point, we need to look at the whole system of which we are part, rather than at one small part at a time. Theologian Thomas Berry gets us off on the right track:

Unaware of what we have done or its order of magnitude, we have thought our achievements to be of enormous benefit for the human process, but we now find that by disturbing the biosystems of the planet at the most basic level of their functioning we have endangered all that makes the planet Earth a suitable place for the integral development of human life itself.

Our problems are primarily problems of macrophase biology ... the integral functioning of the entire complex of biosystems of the planet ....1

The complex biosystem that Berry speaks of is also known as the biosphere. It is our home we are wrecking with our “plundering industrial life patterns,” and the major engine of our civilization’s shortsighted exploitation and destruction is the sprawled city with its flood of traffic, its thirst for fuels, and its vast networks of concrete and asphalt. The car/sprawl/freeway/oil complex reproduces more of itself — a peculiar kind of economic “vitality” — while it paves agricultural and natural land, kills a half million people outright in accidents every year, injures more than ten million, many permanently, and is completely destroying a reserve of complex chemicals that took 150 million years to create, the so-called fossil fuels which should be seen as a fossil chemical treasure chest, an inheritance of the species and a responsibility for carefully restrained use into the deep future. This infrastructure also consumes enormous quantities of steel and energy; in a 1999 television ad, the Ford Motor Company asserted that it uses enough steel to build 700 Eiffel Towers every year. Seven hundred Eiffel Towers of steel racing about the countryside powered by flame, requiring the earth to be paved, and transforming the atmosphere! And that’s only one of a dozen major automobile manufacturers.

Today, we have more than 600 million cars worldwide, and we transform into sprawl development several million acres of land every year, removing it from agriculture, nature, and more pedestrian-oriented traditional towns and villages. Already, in 2004, barely providing a sip for the thirst of American cars for fuel, ten million acres of corn were taken from feeding people to feeding cars.2

The car/sprawl/freeway/oil complex is destroying habitat, and directly and indirectly animals and plants through road kill, noise disruptions, poisonous water runoff, contaminated air, and climate change. Repetitive small car-dependent buildings scattered over vast areas, often made of wood from shrinking forests, not only require enormous quantities of gasoline to maintain, but share walls with no one and lose their energy from heating or cooling to the surrounding air after a single use. Thus scattered, small-building development wastes energy not only for transportation but also for space heating and air conditioning. This four-headed monster of the twentieth-century Apocalypse — cars, sprawl, freeways, and oil — is what we are building and in what we are committing the next generation to live. It is what is largely defining our jobs and many other life activities. It commits us to one of the most expensive and dangerous common activities allowed, namely driving. The car/sprawl/ freeway/oil infrastructure has enormous arms in the form of shipping routes and pipelines, both subject to accidental disasters, and in the form of military forces that maintain constant pressure and occasionally go to war to keep petroleum cheap and flowing.

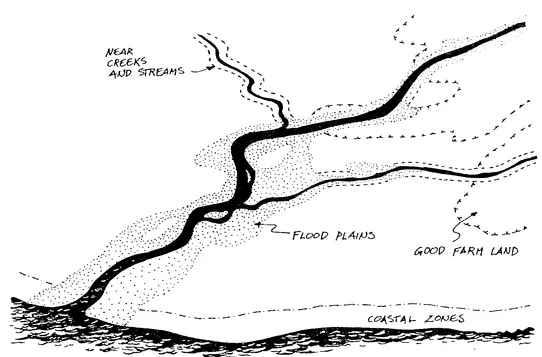

Where not to build. Land uses are the foundation of city design. Avoid flood plains and best farm land, celebrate coastal and waterside with special features. Maintain maximum permeability of surfaces, and to do this, the compact city is the most important solution.

dp n="39" folio="12" ?Because this monster is a “whole system” structure, we can effectively attack it by taking on any one of its four main components. Working against cars, sprawl development, freeways and paving, or oil dependence will help bring down the whole destructive edifice. Even better, we know that if we provide positive alternatives to any of these components, we will be starving the system and nurturing another “whole system” creation: the pedestrian/three-dimensional system. We will be building a whole new infrastructure for a new civilization.

Paul and Anne Ehrlich3 have suggested summarizing the situation in a simple formula: Humanity’s impact (I) on the world’s environment is roughly equal...

Table of contents

- Praise

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Ecocites Become Us

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 - As We Build, So Shall We Live

- CHAPTER 2 - The City in Evolution

- CHAPTER 3 - The City in Nature

- CHAPTER 4 - The City in History

- CHAPTER 5 - The City Today

- CHAPTER 6 - Access and Transportation

- CHAPTER 7 - What to Build

- CHAPTER 8 - Plunge on in!

- CHAPTER 9 - Personal Odyssey

- CHAPTER 10 - Tools to Fit the Task

- CHAPTER 11 - What the Fast-Breaking News May Mean

- CHAPTER 12 - Toward Strategies for Success

- AFTERWORD: REBUILDING NEW ORLEANS

- FURTHER READING

- NOTES

- INDEX

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- Copyright Page