![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Perennial Polycultures: Past, Present, and Future

The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago.

The second best time is now.

— CHINESE PROVERB

Perennial: a plant that lives more than two years.

Polyculture: multiple species in the same space forming interrelationships.

A food forest is an ancient concept reborn for the 21st century. As presented in these pages, a food forest garden is akin to the French potager — or English cottage — garden, a mix of perennials and annuals designed to be both beautiful and to produce an abundance of fruits and vegetables, herbs, and flowers. More specifically, the food forest is a perennial garden built around useful trees and designed to mimic a managed forest ecosystem.

In this chapter we introduce the concept of the food forest garden and perennial polycultures and their role in a sustainable food system. We begin with a review of the natural polycultures and ecological communities we seek to mimic. Next we place the food forest in historical context, from hunter-gatherer societies to tree crops in pre-Industrial Revolution cultures to present day permaculture concepts.

A close examination of Mayan — and similar Native American — horticultural practices illustrates the ancient and ongoing management of food forests by these indigenous forest dwellers. Next we walk though the development of the modern food forest movement. We conclude the first chapter by examining some examples of food forests and perennial polycultures around North America.

If you have drunk shade-grown coffee, or eaten chocolate, most likely you have tasted the products of a perennial polyculture, or food forest. Both cacao (source of chocolate) and coffee grow best in light shade under a canopy tree. The canopy tree may be a legume, such as numerous Acacia species, as well as a wide variety of fruit and nut trees including macadamia, mango, avocado, breadfruit, and useful leguminous hardwoods.

A food forest produces more than food. Many of the plants will have medicinal uses. Craft materials can be grown and gathered. Biodiversity is enhanced through inclusion of habitat for songbirds, beneficial insects, and myriad other critters, which in turn provide valuable ecological services such as pollination and pest control.

A well-designed forest garden is a place to relax and entertain in as well as work. Nature brought home with all the color, song, and buzz of life in the backyard (or perhaps the front yard), provides a connection to the living world that has become scarce in modern life.

Food forests are designed to gather and store rain, carbon, and nitrogen and activate and utilize minerals from the soil for the long term. Properly planned and managed, a food forest can build up the soil while producing yields.

A value and need that has been often overlooked in modern design and the city landscape is beauty. Aesthetics and a beautiful surrounding contribute to better health. The food forest has many opportunities for beauty — indeed it is almost impossible to avoid!

Forest Ecology

Ecology

A basic knowledge of ecology is necessary for both designing and maintaining a food forest garden. Ecology is the study of ecosystems. An ecosystem is a group of organisms living in a dynamic relationship in a shared environment. In nature, plants, insects, and animals have coevolved over millennia, adapting to each other and to the land and climate. Most ecosystems are dominated by perennial plants, whether trees in a forest, or grasses in a prairie. In the next section we will examine forest ecology.

Credit: Sarah A. Jubeck

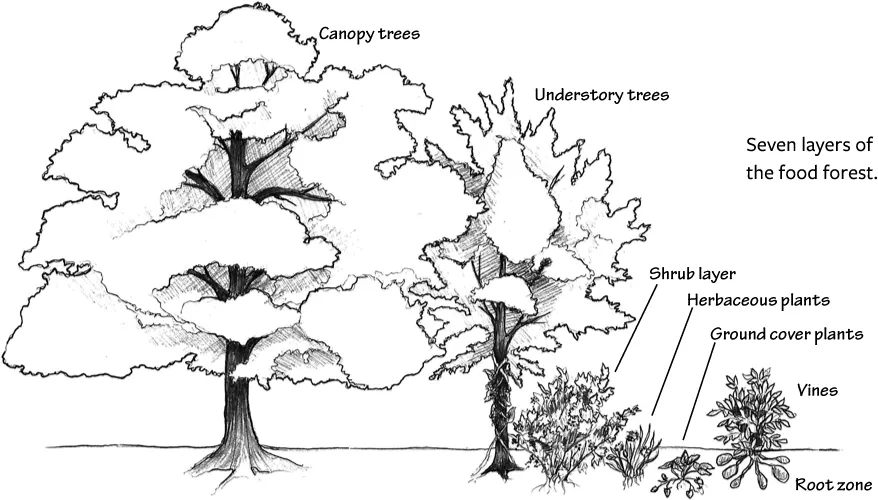

Seven layers of the food forest.

Forests

A natural forest can seem to be a place of mystery. Tall trees are spaced in seemingly random patterns. Smaller trees grow in their shade. Tangled vines sprawl over shrubs and clamber up tree trunks. The ground may be covered with a profusion of plants competing for space and light. Fallen branches and leaves litter the ground, decaying into the earth and smelling of earthy mould. Mushrooms push from the ground and other fungi cling to the trees. Unidentified flying insects zoom past or hover near your head. Small forest creatures scurry among the undergrowth and birds flit among the branches. To one unschooled in ecology, a natural forest may seem wild, jumbled, and unruly.

Studious observation reveals a different story. Seemingly random collections of plants become complex communities woven together into networks of interacting species. Larger trees, forming the canopy, shelter understory companions from weather extremes and suppress grasses from dominating the ground layer. Plants share information through airborne chemicals and nutrients through a subterranean web of roots and mycelium. Seasonal periods of growth and dormancy are timed to maintain essential nutrients in the community. Plants protect the soil from drying winds and heavy rain, allowing rainfall to soak into the soil and be stored in the ground.

Credit: Darrell E. Frey

Perhaps the best use for trees: climbing!

Examining the structure and ecology of the forest will help us understand the patterns of natural perennial polycultures and the various roles plants, animals, and fungi play in the forest. In Chapter 2 we will put this information to use to design and plan productive systems based on this deeper understanding of forest ecology.

A forest is an ecological community. In an ecological community all members of the community interact with one another in a network of relationships. Through photosynthesis plants create new material from air, water, and soil. Different plants have different abilities to extract essential nutrients from the soil, or in the case of legumes, the air. Plants are the base of the food chain providing food, as well as shelter, for animals. As they complete their lifecycles, dying or being consumed by animals, plants return the organic matter to the forest floor. Decomposers, including fungi, insects, arthropods, slugs, snails, and other organisms break down organic matter and return nutrients to the community. Nutrients cycle between the soil, fungi, plants, and animals. The structure of the forest itself moderates the climate, gathers and stores rainwater, and minimizes soil erosion. Pollen and seeds are moved around by air currents and by insects, birds, and other animals. Pest and predator relationships keep a balance of insect and animal populations.

The dominant player in the forest ecosystem is the tree. A natural forest tends to have a mix of tree species, usually of various ages. Different species of trees fill different niches in the system. Some like a dryer soil, some can handle a high water table, some like a warmer south-facing slope, some prefer the cooler northern slopes. The dominant trees form the forest canopy. Understory trees, shrubs, and plants grow best in the shade of other trees. Ground layer plants benefit from the reduced competition from grasses and the moderated climate provided by the upper layers.

Succession is an important concept in understanding forests. Storms, fire, and the death of older trees create clearings in the forest, allowing sun-loving annual and herbaceous perennial plants to germinate and grow. Pioneer species, such as aspen, sassafras, hawthorn, or black locust grow quickly in these clearings. As the pioneer trees mature, second-stage hardwood trees germinate and grow in their shade. When these second-stage trees mature, smaller understory trees fill in among a ground cover of shade-tolerant annuals, fungi, herbaceous perennials, shrubs, and vines.

Eventually, a native forest can develop into a climax forest of mature old-growth trees, with less diversity. An old-growth forest generally includes a mixed-age patchwork. Once again trees die or are toppled by wind storms, or consumed by wildfire. In the newly opened clearings the cycle begins anew.

As we shall see below, traditional native food forests mimic these natural forest clearings. It is likely that these food forests were inspired by indigenous people’s observation of the increased diversity and productivity of the natural forest clearing. Humans have been managing forests for thousands of years. Observation and management of the landscape has been an aspect of human culture since we learned to control fire. So has utilizing plants for making crafts and tools, for medicine as well as food. Certainly our Paleolithic predecessors used fire to control forests and maintain grasslands and savanna landscapes. They first did this to promote the growth of grasses for the grazing animals they hunted. Later, when cultures worldwide developed horticulture, fire was used to reset the succession in the forest to a productive state.

More About Ecology

Community

All life on Earth exists in relationship with everything else. The basic pattern of life on Earth is the network. Also known as the web of life, this network is made up locally of interconnected communities. The forest community, the meadow community, the riverbank community, the aquatic community — each has their own species of plants, animals, and insects that live within them. Birds and animals move between these plant communities as they forage or hunt, transporting nutrients in their daily and seasonal travels.

Biodiversity

A healthy ecosystem teems with life. The diversity of plants and fungi provides food and habitat for wildlife. Predatory animals maintain a balance of animal populations over time. Insects move pollen from flower to flower to promote fruit and seed. What tree is complete without birds? When we shake ripe purple mulberries from branch to sheet on the ground, a great variety of insects falls onto the sheet as well. Leafhoppers, small cicada, fireflies, other small six-legged critters, and assorted lime-green inchworms and various spiders scramble to get out of the bowl as berries are sorted from leaf and twig. The same bird that samples our fruit also consumes hundreds of insect pests and feeds as many to their young. Field mice consume fallen fruit, seeds, and nuts, as do groundhogs, chipmunks, deer, and rabbits. All are part of the great web of life.

Edge

Edge is a term used in ecology to describe the meeting of two or more ecological communities. The space between a meadow and a forest is a third system. The edge may contain species of both ecosystems and many species that prefer the edge. Many plants that might not be able to compete with the dense grasses and forbs of the meadow, or grow in the shade of the forest, thrive on the edge. The edge between two systems provides unique habitats and microclimates that nurture increased diversity of life. A forest garden is often modeled on the forest edge, with a sunny side and a shady side, creating a range of niches in a small area.

Plant Guilds

The plant guild is an important concept in forest gardens. Bill Mollison introduced the concept to permaculture students in Permaculture: A Designers Manual (Tagari Publications, 1998). A guild is a beneficial assembly of plants and animals. The guild concept is derived from the study of natural ecosystems and is the basis of forest garden design. In the pages ahead we will discuss guilds in some detail. To learn more about plant guilds you only need to walk in a natural ecosystem near your home. No plant grows in isolation. Forest landscapes tend to be diverse in structure and species. Many types of plants are found together. Smaller trees and shrubs rise beneath taller trees. Vines climb trees and scramble over shrubs. Smaller perennial and annual plants grow on the ground layer and ground cover plants hug the earth. Beneath the surface roots and tubers are found among fungal mycelium. If you count the layers — subsurface, ground cover, ground layer plants, brambles and shrubs, vines, small trees, and large trees — you can see there are seven layers to the forest. The diversity of species is also plain to see.

Competition or Cooperation

Natural ecosystems include countless interactions between plants, fungi, insects, and animals. Researchers are continually discovering new ways plants communicate, store information, and interact with their environment. Nutrients are shared and exchanged between trees of the same species and, at times, with other species. Smaller shade-tolerant species live in harmony with taller canopy layer trees. However, many plants also have evolved mechanisms to control their neighbors. Numerous plants have been identified that produce allelopathic compounds. These compounds, exuded by roots, bark, and/or leaves, can inhibit seed germination or plant growth. As we will discuss later in this book, various members of the walnut family produce juglone, an allelopathic chemical that can persist in the soil for decades. Many useful plants are resistant to juglone and so a walnut tree guild can be designed. Other plants, though, such as rye grass or goldenrod species, have much less tolerance for these allelopathic compounds.

Perennial Polycultures

As we have seen above, in the natural world diverse perennial plant communities are the basis of the vast majority of ecosystems, whether prairie, savanna, or f...