This is a test

- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

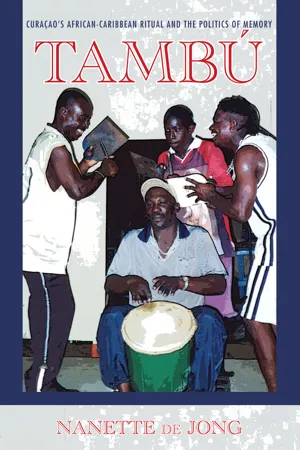

As contemporary Tambú music and dance evolved on the Caribbean island of Curaçao, it intertwined sacred and secular, private and public cultural practices, and many traditions from Africa and the New World. As she explores the formal contours of Tambú, Nanette de Jong discovers its variegated history and uncovers its multiple and even contradictory origins. De Jong recounts the personal stories and experiences of Afro-Curaçaoans as they perform Tambu–some who complain of its violence and low-class attraction and others who champion Tambú as a powerful tool of collective memory as well as a way to imagine the future.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Tambú by Nanette de Jong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Ethnomusicology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

EthnomusicologyPART 1.

Habrí: Here It Is, the History of Tambú!

Até Aki, Historia di Tambú!

1

The Story of Our Ancestors, the Story of Africa

E Kuenta di Nos Antepasados, e Kuenta di Afrika

It is a process which involves the creation of entirely new culture patterns out of the fragmented pieces of historically separate systems.

—JAY EDWARDS

Creolization, the evolutionary development of Afro-Caribbean culture, began when conditions allowed distinct cultural memories to regain meaningfulness within a New World context. Through a process of negotiation, certain histories continued; others became inverted or disappeared altogether. In the end, creolization enabled diverse African cultures to mediate their differences within a new collective construct, legitimizing their cultural presence in the New World. Between layers of antecedents, the creole form exists at the intersection of numerous cultural processes: between social and individual experience, between cultural Selves and Others, between retained and discarded histories and identities, and between colonizers and colonized.

Diverse African nationals entered into a process of creolization, emerging finally as “hybrid societies … mosaics of borderlands where cultures jostled and converged in combinations and permutations of dizzying complexity” (Morgan 1997: 142). The history of creolization, then, traces the development of an alloy-culture from which much has been burned away. The mechanism for this process was set in motion quite inadvertently by white Europeans, whose ambitious economic vision for the New World squeezed maximum profitability out of minimum investment through unpaid slave labor. Toward this end, Africans of many cultural backgrounds, social statuses, and spiritual beliefs were captured and chained, transported within the holds of ships and forcibly relocated to the Caribbean, where they labored on the plantations or were resold elsewhere in the Americas.

According to Sidney Mintz and Richard Price, the multiplicity of African cultures “reach[ing] the New World did not compose, at [that] moment, groups” (1992: 10). Rather, the experience of slavery united the Africans, however diverse their backgrounds and cultures, compelling them to conform to the standards and expectations of the dominant white society. Although slavery eventually ended, emancipation failed to bring assimilation into the dominant culture, which was still unwilling to embrace blacks as equals. Emancipation, when it came, merely had the effect of cooling the New World “melting pot,” and new cultural identities began to congeal. In the end, creolization enabled diverse African peoples to mediate differences within a new collective construct, and to redefine a cultural presence in the New World (Khan 2004: 4).

Montamentu, the religion for which Tambú served as accompaniment, decrees a modern cultural foothold based on abstract perceived Africanness, a hybrid adaptation of remembered African origins marked by their adaptation to the New World experience. Its emergence indicated the formation of a common identity and collective memory among the Afro-Curaçaoan people. To study Montamentu, then, is to examine one of the earliest examples of Afro-Curaçaoan collective memory. Its study reveals a dendrochronology—a history articulated in layered chapters. Just as cross sections of an ancient tree reveal secrets of climatology and other life circumstances to those able to interpret what they see, so too does the cultural stratum of Montamentu reveal to ethnologists the changing historical contexts of its growth and survival. Because creolization is bound to political and social stakes and meanings, unraveling its threads within Montamentu uncovers hidden complexities distinct to Curaçao’s unique cultural encounters. Today’s historians confront in Montamentu (and creolization in general) that which Trouillot calls the “ultimate challenge [of uncovering cultural] roots” (1995: xix).

Of the total 500,000 or so Africans who passed through Curaçao during the slave years, only some 2,300 were to remain permanently on the island. As previously stated, this created on Curacao two distinct slave communities: the negotie slaven, which was in a constant state of flux; and the other, the manquerons, which, much smaller in number, was static. The continuing turnover and growing diversity of the negotie slaven brought fresh supplies of African traditions to the island. Manquerons, forced to remain on Curaçao, were generally pressed into service as common laborers (Postma 1975: 237; Goslinga 1971: 362). As may be surmised, they came to connect with the dominant Dutch on an ongoing personal basis. Servants gained closest access to Dutch culture, often quartered within the landhuis (“plantation house”) located on the grounds of estates they served, but every level of interaction and cultural exchange took place (Hartog 1961: 173). On the other hand, outside of marketing negotie slaven to other island plantations, Curaçaoan slavers maintained very little close contact with the negotie slaven. They were imprisoned as they were within the confines of Curaçao’s two large detention camps—both located far from the homes of the Dutch; and, during their stay on Curaçao, their care fell to the island’s lowest manqueron servants. Neither black subgroup represented to the Dutch a separate entity (Postma 1975: 271). The exchange of ideas between the negotie slaven and the manquerons produced a number of cultural by-products, including the Afro-syncretized religion, Montamentu. Because Dutch interests were largely focused on trade and profits, the goal of Christian proselytizing (which motivated other European colonialists) was not a high priority, and Montamentu, when it did evolve, was met with little interference from the island’s dominant culture.

Africans taken into slavery through the Dutch West Indische Compaigne came predominantly from two geographical regions: the Angolan coast (roughly the area between Cameroon and the Congo River) and the region of West Africa. While the cultural foundation of Montamentu may be traced to these two African regions, sleuthing out the specific Old World antecedents presents a Gordian knot unlikely to be fully disentangled. Records, where they exist, tend to offer inconclusive evidence of slave origins, and often concentrate (nearly exclusively) on the Africans captured in the western coastal regions. While it is likely much will never be fully understood, modern research continues to pursue the challenge. Employing nontraditional means of deciphering the evidence becomes not just a possible option, but a real necessity.

The examination of ship logs kept by Dutch slavers yields cargo descriptions and lists from which theories of possible African derivations can be construed. It should be borne in mind, however, that such cargo descriptions were recorded not so much to document the nationalities and cultural backgrounds of African people as they were to inscribe inventory of trade. Lorna McDaniel shows that one practical reason for recording the national backgrounds of slave cargoes in the logs of ships was to better manage prisoners during the Middle Passage. Since certain African nations were involved in ongoing wars with other nations, separating these battling culture groups during the long journey was essential (McDaniel 1998: 36).

Because the ship logs emerged for reasons of trade, no standard classification system was developed, or even encouraged. As a result, misspellings and spelling modifications frequently occurred in the logs. Decoding these flaws represents a constant challenge to anyone attempting to use them as historical references. Often the African port of exit was used as a nation name. As occurred, Africans were captured in one area of Africa and then sold in another. These Africans usually were logged into the ship documents by the name of the African port of exit, rather than their actual nation of origin. Cape Lahou (also written as Cape LaHou) is one such example. Located on the mouth of the Ivory Coast, Cape Lahou became a terminology used for nation distinction (Curtin 1969: 185–186). Similarly, the trading station of Kromatine (also spelled Cromanti, Kormantine, and Cormantine) in Ghana was employed for identification purposes. Frequently, the language of a culture group became used as national title. Mallais (also written as Malais and Malé) was the language spoken by the Ewe-Fon people of Dahomey, yet during slavery Mallais evolved into a title used by slave captains to distinguish nationality (Wooding 1981: 21–23). Furthermore, ship’s logs were rarely adjusted to reflect the innumerable prisoners who, having perished at sea, were unceremoniously tossed overboard (Curtin 1969; McDaniel 1998; Goslinga 1971). Although slave ship logs are a good starting point in the search for African origins in the Americas, they remain problematic, demanding constant review.

It must also be noted that slaves of certain African nationalities were perceived to be superior to others, and therefore might be expected to command top prices in the marketplace. Adding particularly to the confusion today is the fact that unprincipled proprietors are known to have deliberately misassigned national origins in order to capitalize on the higher prices. Dutch historian Jan Jacob Hartsinck speaks to this phenomenon in Beschrijving van Guiana of de Wilde Kust, in Zuid-Amerika (1770). Hartsinck gives this example of how some Dutch notoriously misrepresented the national background of incoming Africans: “The best slaves in the land [according to popular preference] have scratches on their foreheads” (referring to culture-specific decorative scarring). Hartsinck reports that some slavers were not above inflicting similar physical markings upon African slaves of other nationalities, hoping to fool purchasers into paying higher prices for their slaves. In the words of Hartsinck:

We hope that our readers will not be displeased, especially those who are interested, if we give some descriptions of various kinds concerning the nature and marks [tokens, signs] of these people that distinguish them from each other; but one must be careful, however, because black slave-dealers may change these marks to their advantage and in that manner [transform] the poorer kind of Negroes [into something better than what they really are]. (Hartsinck 1770: 918)

European participation in the African slave trade began with the Portuguese, whose interest expanded geometrically when it colonized immense Brazil, literally encompassing half a continent (Alden 1973; Boxer 1969). African slave labor comprised virtually the entirety of the Brazilian plantation workforce, making Brazil the leading importer of African slaves in the New World (Rawley 1981: 40–41). The bulk of the slave workforce came from Angola, and Philip Curtin estimates Angolans represented over 70 percent of Brazil’s entire slave population (Curtin 1969). When Portugal found itself drawn into internal conflicts with Spain, its overseas territory became a secondary concern—and easy prey for outside takeovers. The Netherlands (known during the slave years as the United Provinces or Dutch Republic) was the major beneficiary of the weakened empire. The largest Dutch acquisition, comprising most of northeastern Brazil, was rechristened New Holland, and became the first Dutch plantation colony. Administration of the Dutch Republic’s New World possessions was left to the West Indische Compaigne, chartered in 1621 (Boxer 1957: 27; Emmer 1981: 71–72; Postma 1990a: 15).

The WIC soon realized that New Holland’s sugar-based plantation economy stood in need of an increasingly large workforce. “It is not possible to accomplish anything in Brazil without slaves,” were the words of New Holland’s first acting governor (Boxer 1957: 83). Unable to entice enough mainland Dutch to relocate to New Holland, the WIC had little choice but to persuade farmers who served under Portuguese rule to remain. Those farmers who agreed to stay during the Dutch occupation made the provisional request that an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Get Ready!

- Part 1. Habri: Here It Is, the History of Tambú!

- Part 2. Será: Get Ready! Get Ready!

- Conclusion: Are You Ready? Are You Ready to Hear the History of Tambú?

- Glossary of Terms Referring to Tambú

- Bibliography

- List of Interviews

- Index