eBook - ePub

Seeking a Sanctuary, Second Edition

Seventh-day Adventism and the American Dream

This is a test

- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Seeking a Sanctuary, Second Edition

Seventh-day Adventism and the American Dream

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The completely revised second edition further explores one of the most successful of America's indigenous religious groups. Despite this, the Adventist church has remained largely invisible. Seeking a Sanctuary casts light on this marginal religion through its socio-historical context and discusses several Adventist figures that shaped the perception of this Christian sect.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Seeking a Sanctuary, Second Edition by Malcolm Bull,Keith Lockhart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Adventist Theology

CHAPTER ONE

Authority

BORN IN 1827, the daughter of a hatter from Gorham, Maine, Ellen Gould Harmon had an uneventful childhood. At the age of nine, however, she was accidentally hit on the head by a stone, and her injuries prevented further formal education. She first heard about the imminent end of the world at twelve, when her parents took her to a meeting that William Miller was holding in her neighborhood. She waited until she was fifteen before fully committing herself to his movement, but when she did, she was expelled from the Methodist Church, into which she had been born, along with other members of her family.1

Her first vision occurred when she was still only seventeen, two months after the débâcle of October 22, 1844. This was a comforting revelation in which she saw that the saints would ascend from the earth to the Holy City after all. She continued to have such visions until 1878, although the frequency declined markedly in the 1860s, and she probably did not have more than about two hundred altogether. In 1846 she married James White, formerly a minister of the Christian Connection and a fellow disappointed Millerite.2 Together they worked for the Seventh-day Adventist denomination until James’s death in 1881. After this, Willie, one of Ellen White’s two surviving sons, became her closest confidant. She spent most of her life in the northern United States, but she visited Europe from 1885 to 1887 and lived in Australia between 1891 and 1900. On her return to America she settled near St. Helena, California, where she died in 1915. She never accepted formal office, thereby establishing a distinction between her charismatic role and the bureaucracy of the church. But throughout her long career, Ellen White wrote and spoke to Adventist audiences, who received her in the belief that she was the “spirit of prophecy” identified in the book of Revelation.3

In the beginning, her religious experience followed a pattern similar to that of many previous mystics. In 1842 she went through a typical “dark night of the soul” occasioned by her fear of praying in public: “I remained for three weeks with not one ray of light to pierce the thick clouds of darkness around me,” White related later. “I then had two dreams which gave me a faint ray of light and hope.”4 In one of these, she ascended a stairway. At the top she was brought to Jesus. Like other female mystics, such as St. Teresa, she was immediately attracted by his beauty, but she had to be reassured before being able to experience the full joy of his presence.5 Shortly after this dream, she uttered her first public prayer, during which she experienced an overwhelming sense of love for Jesus: “Wave after wave of glory rolled over me, until my body grew stiff.”6 Just as St. Teresa had written of her transverberation that her soul could not “be content with anything less than God,” so White wrote, “I could not be satisfied till I was filled with the fullness of God.”7 This intense desire for experience of the divine presence is an aspect of White’s development that is often overlooked. Her exceptional religious propensities originated, not from a search for doctrinal or ethical information, but from a simple desire to feel the love of Jesus.

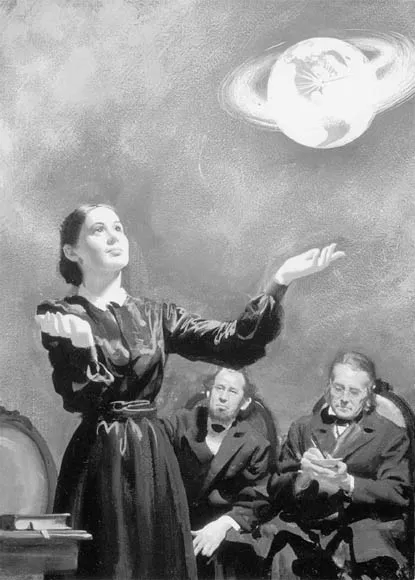

Such experiences were accompanied by striking physical manifestations, and these were fundamental to her acceptance as a source of authority within the emergent denomination. At the onset of vision, she usually uttered the words “Glory! Glory! Glory!” She would enter a trance-like state, stop breathing, and because of this apparent cessation of normal bodily functions, seem “lost to the world.” This phenomenon was very important to her contemporaries, who made a concerted effort to establish her indifference to earthly things. They covered her nose and mouth, held a mirror up to her face, pinched her, felt her chest, pretended to hit her, and shone bright lights in her eyes, all in an effort to see if she would breathe, flinch, or blink.8

The attempt to establish that Ellen White was lost to this world was based on the implicit understanding that if she were, she would be more open to the spiritual world.9 In her first vision, she had experienced it so directly that afterwards she wept and felt homesick for the better land she had seen.10 This ability to see the heavenly world was vital to the early Adventists, who, after the Great Disappointment, had begun to doubt that what was visible on earth revealed eternal truth. Thus, through her revelations of heaven, Ellen White could inform the faithful of what ought to be believed on earth. The most literal example of how this worked was White’s vision of the Ten Commandments written on tables of stone in the heavenly sanctuary. Reading them, she observed that God had not changed the wording of the fourth commandment in favor of Sunday, the first day of the week. Therefore, she concluded that God required the observance of Saturday, the seventh-day Sabbath, on earth.11

Figure 3. Lost to the world: an idealized Ellen White in vision, with the two other members of Adventism’s founding triumvirate, James White, left, and Joseph Bates, taking notes. Harry Anderson, Streams of Light, watercolor, 22" x 30", 1944. © Review and Herald Publishing Association.

This approach attracted criticism from the church’s early opponents. In 1866, in The Visions of Mrs. White Not of God, two disaffected Adventists, B. F. Snook and W. H. Brinkerhoff, alleged that many of the things Ellen White claimed to see in heaven were false, or not in accord with descriptions in Scripture.12 Their critique was taken up by the Sunday-keeping Advent Christians, who, like the Adventists, were previously followers of William Miller. They pointed out that Ellen White had never had the revelation about the Ten Commandments while she was a Sunday observer herself. It was only after she received “the theory of the seventh-day Sabbath at the hand of a man,” one Advent Christian wrote in 1867, that her visions came into “harmony with her new feature of theology.”13 Such objections, and the accusations of Snook and Brinkerhoff, were answered by the church writer and editor Uriah Smith in a booklet issued in the following year. He maintained that what White saw in heaven was accurate, in harmony with Scripture, and the basis of sound Adventist doctrine.14

Even so, it was some time before the “Testimonies,” as her writings became known, led rather than followed the group to which they were addressed. For the first ten years, she tended to confirm belief rather than admonish believers. Indeed, the quantity of her output was regulated by the attitude of the community. As she herself noted in 1855: “The reasons why visions had not been more frequent of late, is, they have not been appreciated by the church.”15 In practice, the extent to which the visions could be appreciated by Adventists was dependent on the frequency of their publication. As the church expanded, its chief means of communication became the press. Ellen White’s religious experience, once validated to the scientific satisfaction of her peers, became the raw material on which a publishing industry was based. The financial and technological development of Adventist publishing may not have influenced White’s experience, but it certainly determined the extent and form in which that experience could be communicated.

The nineteenth century witnessed a revolution in American publishing, and the Adventist press followed the general trend.16 As technology improved, it became easier to produce longer books. This advance also necessitated a constant flow of copy, an example of which can be seen in the books dealing with the “great controversy” theme—White’s classic exposition of the ongoing battle between good and evil. The central idea of the great controversy is a cosmic struggle between Christ and Satan, which the prophetess traced from its origins in heaven to its final resolution at the close of the millennium. The great controversy theme first appeared in the first volume of Spiritual Gifts in 1858. Material from the Spiritual Gifts series was expanded to form the four-volume Spirit of Prophecy series in 1870–1884. Between 1888 and 1917, this series was transformed into the Conflict of the Ages series that comprised five books: Patriarchs and Prophets and Prophets and Kings (accounts of Old Testament history), the Desire of Ages (a biography of Christ), Acts of the Apostles (a history of early Christianity), and the Great Controversy (which related the battle between Christ and Satan from the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 to the millennium at the end of time).

In the course of this process, the content and style of the books underwent significant alteration. Some idea of the stylistic changes may be gained by comparing the account of the fall of man given in volume one of Spiritual Gifts (1858) with the accounts found in volume one of the Spirit of Prophecy (1870) and in volume one of the Conflict of the Ages series, Patriarchs and Prophets (1890). Ellen White’s writing in 1858 reveals both the deficiencies in her education and the intensity of her experience. The narrative style is simple but compelling. The account is given in the past tense, not so much because the events described happened in the past as because the visions were in the past. By 1870 White had acquired many of the techniques of contemporary religious novelists.17 Making much use of the vivid present, she emphasizes narrative detail and the emotional state of the characters involved. The short sentences found in Spiritual Gifts are filled out by abundant adjectives and adverbs and expanded by additional clauses. Thus the angels that in 1858 “gave instruction to Adam and Eve,” in 1870 “graciously and lovingly gave them the information they desired.”18 While in 1858 Eve simply “offered the fruit to her husband,” in 1870 “she was in a strange and unnatural excitement as she sought her husband, with her hands filled with the forbidden fruit.”19

In 1890 a much more sophisticated writer appears, concerned not with narrative details but with moral exhortation. The vivid present is replaced by past or future tenses, depending on when the events described took place. The simple connectives used in 1870 give way to dependent clauses of time and purpose. Abstract nouns make an increasing appearance, along with the passive voice and impersonal constructions. The statement that “Satan assumes the form of a serpent and enters Eden” gives way to the observation that “in order to accomplish his work unperceived, Satan chose to employ as his medium the serpent—a disguise well adapted for his purpose of deception.”20 White also cuts back on the superfluous use of adverbs in favor of a richer vocabulary. So the serpent that in 1870 “commenced leisurely eating” is in 1890 “regaling itself” with the same fruit.21

While there is no doubt that these developments indicate an increase in the literacy of the prophetess, Ellen White’s earliest work shows an intuitive awareness of the dramatic potential of narrative that is obscured by the sentimental and moralizing tone of her later books. This diminution in the power of her language is, however, partly explained by the fact that her books decreasingly represented her unique experience. As the demands on her time increased, she relied on assistants to do research and prepare copy. Moreover, the outlines of her narratives were frequently supplemented by material drawn from other writers. This is particularly true of the Conflict of the Ages series. Patriarchs and Prophets and Prophets and Kings owe something to Daniel March’s Night Scenes of the Bible and to books by Alfred Edersheim. The Desire of Ages is indebted to both of these authors and to William Hanna’s Life of Christ. The Acts of the Apostles borrows from William Conybeare and John Howson’s The Life and Epistles of the Apostle Paul, as well as from two of White’s favorite writers, John Harris and Daniel March. The Great Controversy contains substantial sections from the historians J. A. Wylie and Merle D’Aubigné.22

None of this was generally known until it was exposed by a former Adventist, Dudley M. Canright, in his Seventh-day Adventism Renounced, of 1889. Accusing White of “stealing her ideas” from other authors, Canright calculated that up to a quarter of all her writings had been plagiarized up to this point.23 This revelation cast renewed doubt on White’s claim to heavenly inspiration. But it was a question of production as well of inspiration. As one historian has noted, nineteenth-century publishers “encouraged high productivity in their authors,” since they felt that “to keep up demand, the public must be constantly reminded that a particular writer existed.”24 Adventist publishing was no exception, and White’s increasing use of sources enabled the press to engage in the almost continuous publication of “new” material. This, in turn, enabled the church to disseminate her somewhat diluted influence more widely. Thus, the authority accorded to White by the small circle familiar with her visions expanded to encompass a much wider audience. Since many of these people had no contact wi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- Introduction: Public Images

- Part 1. Adventist Theology

- Part 2. The Adventist Experience and the American Dream

- Part 3. Adventist Subculture

- List of Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliographical Note

- Web Guide

- Index