This is a test

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Lauri Suurpää brings together two rigorous methodologies, Greimassian semiotics and Schenkerian analysis, to provide a unique perspective on the expressive power of Franz Schubert's song cycle. Focusing on the final songs, Suurpää deftly combines textual and tonal analysis to reveal death as a symbolic presence if not actual character in the musical narrative. Suurpää demonstrates the incongruities between semantic content and musical representation as it surfaces throughout the final songs. This close reading of the winter songs, coupled with creative applications of theory and a thorough history of the poetic and musical genesis of this work, brings new insights to the study of text-music relationships and the song cycle.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Death in Winterreise by Lauri Suurpää in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Classical Music1 Genesis and Narrative of Winterreise

1.1. The Genesis of Winterreise

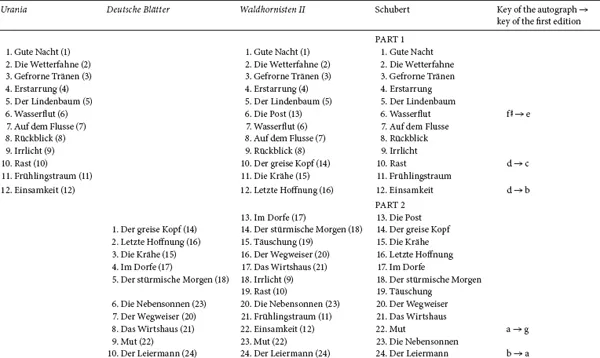

The genesis of both the poems and the music of Winterreise is complex and took place in several stages.1 The poet Wilhelm Müller published the verses used in the cycle in three separate collections (table 1.1). The first twelve poems initially appeared in Urania: Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1823. Susan Youens (1991, 22) has argued that Müller first considered these twelve as a complete and closed whole. Yet Müller published ten more poems, still in 1823, this time in Deutsche Blätter für Poesie, Litteratur, Kunst und Theatre. In 1824 these two sets appeared along with two additional poems (“Die Post” and “Täuschung”) in a publication called Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten II. This was the first time the twenty-four poems were published together. In this third publication, Müller drastically changed the order of the poems. Hence, the overall course of the final cycle differs significantly from what would have happened if the first two publications had simply been conjoined and supplemented by the two added poems. Müller’s reasons for changing the order or for supplementing the original Urania poems in the first place are not known.2

Schubert composed Winterreise in two stages, and, accordingly, the cycle consists of two parts, first published separately. He apparently intended the first part, songs 1–12, as an independent whole. It is likely that Schubert first discovered only the twelve poems published in Urania and set these without knowing the other twelve. As table 1.1 indicates, the order of the first twelve songs of Winterreise corresponds exactly to that of the Urania poems. Both the manuscript of the first part and the engraver’s fair copy have the word Fine after the twelfth song, which supports the assertion that part 1 was originally intended as a closed cycle.3 In the first edition, the word Fine has been deleted. The autograph manuscript of part 1 is dated February 1827. As Robert Winter (1982, 241) has shown in his manuscript study, Schubert had the kind of paper used in the autograph of part 1 from September 1826 to May 1827; thus, this autograph must have been finished by May 1827 (an exception being the revision of “Rückblick,” which could not have been composed before June 1827).

Schubert apparently discovered the twenty-four poems published in Waldhornisten only after having completed part 1. As table 1.1 shows, he did not change the order of the first twelve songs as Müller had done with the poems, thereby keeping part 1 as in Müller’s original scheme. Schubert also preserved the order of the new poems as they appear in Waldhornisten, only he put them in sequence in part 2 instead of scattering them among the poems of part 1 as Müller had done. There is only one exception to Schubert’s adherence to Müller’s order: he reversed the positions of “Die Nebensonnen” and “Mut.”4 As a result, the overall narrative formed by Schubert’s Winterreise differs from that in Müller’s complete cycle in Waldhornisten.

Table 1.1. Order of the poems in Wilhelm Müller’s three publications and in Schubert’s cycle

The autograph manuscript of part 2 is a fair copy dated October 1827. Winter (1982, 248) has demonstrated that the songs were written on paper that Schubert used from October 1827 to April 1828. But since the autograph is a fair copy, Schubert must have composed the songs earlier, and sketches for “Mut” and “Die Nebensonnen” can be dated from June to September 1827, suggesting that Schubert was working on the songs of part 2 at that time (246, 248). The documentary evidence, then, supports the assertion that he began to work on part 2 (sketching it at least as early as June 1827) only after having completed part 1 (which was finished by May 1827).

Five of the songs appear in different keys in the first edition from those found in the autograph manuscript (see the last column of table 1.1). Youens has suggested that these transpositions might have been made at the request of the publisher, Tobias Haslinger, in order to avoid uncomfortably high pitches for the singer. The publisher might have feared that a high tessitura would reduce the market for the cycle (Youens 1991, 95–96).

The above-drafted genesis of Winterreise raises two questions important for our present concerns: Should Müller’s final ordering of the poems (as found in Waldhornisten) be taken into consideration in the overall narrative of Winterreise? Should the songs that were transposed be analyzed in the keys found in the manuscript or in the first edition?

As for the first question, since this study deals with Schubert’s Winterreise, it seems justifiable to discuss the narrative only as it appears in the song cycle. (This does not mean, of course, that the comparison of the two orderings would not be an interesting topic for a separate study.) The second question is more problematic. Scholars have not been unanimous in considering the relative merits of the two transpositions for the overall tonal scheme. Christopher Lewis (1988, 58–66) has an interpretation of the overall dynamic of the cycle that relies on the keys of the autograph, while Kurt von Fischer suggests that the keys in the first edition are better related to the text (Fischer’s view is discussed in Lewis 1988, 62). Youens (1991, 95–99), in turn, has suggested that the original keys might have had poetic implications for Schubert but that the transpositions too form an effective, if somewhat different, dramatic tonal plan. Finally, Anthony Newcomb has argued that “the transpositions do not much change the overall effect of tonality in the cycle” (1986, 169).

Here I will examine the songs in the keys of the first edition. Schubert helped to prepare the engraver’s copy of part 1, and he proofread part 2, so these are the final keys that he saw and evidently accepted. Moreover, we cannot know for sure what led to the transpositions, and the situation might even be different for different songs. In the autograph manuscript of part 1, Schubert (1989, 33) gave instructions to transpose “Rast.” I have not had the opportunity to study the original autograph, but judging from the facsimile edition (Schubert 1989), it appears that the ink in these instructions is the same as in some of the final changes and additions to the song. So it is at least conceivable that the idea of transposition was Schubert’s own, born at the same time as other final changes.5 The other two transposed songs from part 1 (“Wasserflut” and “Einsamkeit”) appear in the new keys only in the engraver’s copy.6 But even here the idea of transposition might have originated with Schubert. We know that he worked closely with the copyist when preparing the engraver’s copy. In her introduction to the facsimile edition, Youens has observed that “passages that differ markedly from the autograph appear in the Stichvorlage with no trace of correction [by Schubert]” (Schubert 1989, xvinl8). Thus, these alterations are not mistakes by the copyist but rather changes suggested by Schubert himself. Again, it is at least conceivable that Schubert had second thoughts about the keys and had these changed when the engraver’s copy was prepared. The situation is different in part 2. Here the manuscript contains transposition instructions in the hand of Tobias Haslinger, the publisher.

The circumstances are thus complex, and it is not possible to know Schubert’s thoughts on the situation. As a result, it is not clear whether the new keys should be handled the same in every case. For example, should the new key for “Rast” be used (since it has Schubert’s own instructions for transposition, possibly made during the final changes) while analyzing the other songs in the original keys? Or should the new keys be used in analyzing part 1 while opting for the original ones in part 2, since the instructions to transpose the songs are in the publisher’s hand? To avoid such questions, which are unanswerable given the current knowledge of Winterreise’s compositional history, I will use the keys in the first edition, which we know Schubert accepted, or at least knew about, as he prepared his work for publication.

Some associations among the songs will certainly be lost.7 For example, if “Einsamkeit” remains in the original D minor, it provides a firmer conclusion for part 1: the music returns to the key of the opening song, so that D minor frames part 1 and hence underlines its unity.8 But the transpositions also create new connections. For example, if “Wasserflut” is transposed into E minor, then songs 5, 6, and 7 form a tonally unified whole (all in E major or minor). In spite of such fluctuating connections, I do not believe that the keys of the five transposed songs are of primary importance for the overall course and unity of Winterreise. I will return to this issue in section 13.2, which discusses the large-scale harmonic organization of the second part of Winterreise.

1.2. Underlying Narrative in the Poems of Winterreise

Many scholars dealing with Winterreise have discussed the degree to which the poems form a unified plot or a thoroughgoing underlying narrative. The cycle is often compared to Die schöne Müllerin, and, by comparison, the poems of the earlier cycle seem to form a much clearer plot. There are also studies that completely deny any overarching trajectory in Winterreise. Cyrus Hamlin, for example, has suggested that “the twenty four poems published by Wilhelm Müller that make up this cycle categorically resist and oppose any sense of narrative” (1999, 116), while Charles Rosen has spoken about the “reduction of narrative almost to zero” (1995, 196). The commentators who deny any plotlike trajectory do not necessarily argue, however, that the cycle lacks unity. But this unity is seen to grow out of the inner sentiments of the protagonist rather than from outward actions.9 Thrasybulos G. Georgiades, for example, has suggested that Winterreise “is governed throughout by only one theme, varied in different ways: the unhappy me, which is mirrored in nature (or some other factor: ‘Die Post,’ ‘Der Leiermann’); the innermost being, whose state is defined through its reflection in the outer: ‘My heart, in this brook do you now recognize your own image’ (‘Auf dem Flusse’), ‘My heart sees its own image painted in the sky’ (‘Der stürmische Morgen’)” (1967, 359). Youens, in turn, has argued that Winterreise “is a monodrama, a predecessor of Expressionist interior monologues. In such works as . . . Arnold Schoenberg’s Erwartung, a single character investigates the labyrinth of her or his own psyche in search of self-knowledge, escape, or surcease from pain, a flight inward into the hothouse of imagination rather than outward into the real world” (1991, 51).

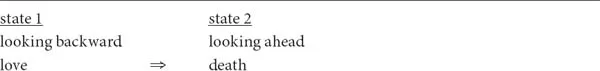

Table 1.2. Underlying narrative of Winterreise

Despite the sparseness of concrete goal-directed action, I suggest that the poetic cycle does have a kind of plot, albeit a vague one. This narrative consists only partly of actual events. The main unifying features occur in the protagonist’s inner world, as is also suggested in the comments quoted from Georgiades and Youens above. But I would argue that this inner world is not invariable throughout Winterreise. Rather, it changes during the cycle, and this change is related to one of the most pervasive features of the wanderer’s inner thoughts: the juxtaposition of reality and illusion. There are two fundamental forms of illusion in the poems: one is associated with the love that has been lost, while the other is associated with a longing for death. (Death may also be understood more generally to symbolize a state of peace wherein misery is no longer felt. I will return to this issue in section 2.3 and chapter 14.) The first illusion looks back to the past, while the second looks ahead to something the protagonist hopes to attain in the future. The cycle moves from the first illusion, which governs part 1, to the second illusion, which governs part 2.

Since there is a transformation from the first illusion to the second, there is also narrative activity, clarified in table 1.2. This underlying narrative consists of two states and a movement from the first state to the second. In both, the protagonist tries to reach something that he ultimately cannot attain and that therefore remains an illusion; in the first state, he looks back to the lost beloved, while in the second state, he looks ahead to death, for which he longs. Both states portray a situation that is unpleasant for the narrator, since he cannot have the object for which he yearns. The protagonist’s temporal perspective on these two forms of illusion (love and death) is always the present moment in his journey. With some brief and fleeting exceptions, the wanderer knows that the illusion he contemplates and longs for is not, and cannot be, real. This knowledge makes his longing even more desperate.

Individual poems by no means elaborate on this underlying narrative (a shift from looking back to the lost love to looking ahead to the hoped-for death) consistently enough to form an unequivocal, linear trajectory that spans the cycle. In this sense I agree with the scholars referred to above who state that Winterreise has no clear narrative. Yet I would like to suggest that the cycle can be loosely divided into connected groups of poems and that these groups consistently elaborate on the underlying narrative shown in table 1.2. Here I offer a tentative division of the poems into thematic groups, based on the texts alone, without taking the music into consideration. In chapter 13, which examines cyclical aspects of part 2 of Winterreise, I will also discuss the overall organization from the musico-poetic perspective and, more formally, the foundations of my proposed textual narrative.

I divide the poems into nine units, based on thematic factors. The units are not equal in length: some include as many as five poems, while others consist of only one. Several of the units include poems that contrast with others in their group, thereby challenging the cohesion of the units. In such instances the unity is suggested by the larger context: the thematic contrast among contiguous units speaks for the unity within the intervening group. Occasionally, some poems that contrast with their own unit might, from the perspective of content alone, be better suited to some other group. I will not, however, assemble nonadjacent poems belonging to different units. In other words, my division is based only on thematic links between contiguous poems, or groups of poems (a syntagmatic perspective), rather than on general thematic associations that do not take the poems’ location in the cycle into account (a paradigmatic perspective).10 Since here my aim is to indicate how the underlying narrative shown in table 1.2 is elaborated upon in individual poems, the syntagmatic perspective seems justified. I will, however, comment on associations among the groups, since these, of course, form an important strand in the cycle.11

1. Departure (Poems 1–5)

In this group, the wanderer begins his journey. He leaves the town where his beloved lives, explaining the reasons for his departure. This group is unified by references to places and objects associated with the beloved: in “Gute Nacht” the speaker leaves her house and walks past its gate; in “Die Wetterfahne” he looks at the weather vane on the roof of the beloved’s house; in “Erstarrung” he looks at the meadow where they walked in the summer; and in “Der Lindenbaum” he walks past a linden tree in whose shade he spent happy times in the past. In each of these poems, the concrete references are juxtaposed with comments on the speaker’s present inner state, the misery resulting from...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Note on the Translations of the Poems

- Part 1. Background

- Part 2. Songs

- Part 3. Cycle

- Notes

- References

- Index