eBook - ePub

A Performer's Guide to Seventeenth-Century Music, Second Edition

This is a test

- 560 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Performer's Guide to Seventeenth-Century Music, Second Edition

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Revised and expanded, A Performer's Guide to Seventeenth Century Music is a comprehensive reference guide for students and professional musicians. The book contains useful material on vocal and choral music and style; instrumentation; performance practice; ornamentation, tuning, temperament; meter and tempo; basso continuo; dance; theatrical production; and much more. The volume includes new chapters on the violin, the violoncello and violone, and the trombone—as well as updated and expanded reference materials, internet resources, and other newly available material. This highly accessible handbook will prove a welcome reference for any musician or singer interested in historically informed performance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Performer's Guide to Seventeenth-Century Music, Second Edition by Jeffery Kite-Powell, Stewart Carter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

VOCAL/CHORAL ISSUES

1

National Singing Styles

Divers Nations have divers fashions, and differ in habite, diet, studies, speech and song. Hence it is that the English doe carroll; the French sing; the Spaniards weepe; the Italians…caper with their voyces; the others barke; but the Germanes (which I am ashamed to utter) doe howle like wolves.

–Andreas Ornithoparcus, Musicæ active micrologus (1515), translated by John Dowland, 1609

As to the Italians, in their recitatives they observe many things of which ours are deprived, because they represent as much as they can the passions and affection of the soul and spirit, as, for example, anger, furor, disdain, rage, the frailties of the heart, and many other passions, with a violence so strange that one would almost say that they are touched by the same emotions they are representing in the song; whereas our French are content to tickle the ear, and have a perpetual sweetness in their songs, which deprives them of energy.

–Marin Mersenne, Harmonie universelle, 1636

Although one might assume that the human voice has not changed over the centuries, many elements of seventeenth-century vocal performance practice differed considerably from modern singing. There was no single method of singing seventeenth-century music; indeed, there were several distinct national schools, each of which evolved during the course of the century. The differences between French and Italian singing were widely recognized in this period, and the merits of each were debated well into the eighteenth century.1 There were also distinctive features in German, English, and Spanish singing.

Though the Italian school was the most influential outside its borders, much less source material by Italians survives than by Germans. In reading the sources, confusion inevitably arises regarding terminology and the repertories and regions to which it is applied. Writers use the same term, such as tremolo, with different meanings, which in turn may not correspond to modern usage. Though laryngology was not an established science in the seventeenth century, some writers ventured into the area of vocal physiology, frequently creating more confusion than clarification.

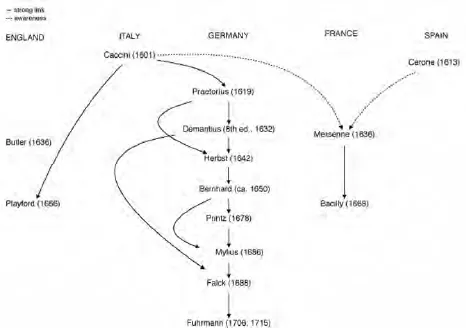

FIGURE 1.1. Linkage of selected seventeenth-century singing treatises.

Examining the linkages among treatises reveals both continuity and evolution within a national style over time and crosscurrents among regions. Figure 1.1 shows this linkage for Italian and German sources. While there was considerable musical exchange between Italy and Germany, there are still characteristics that give the music and its performance style an Italian or German “accent.”

Most of the defining characteristics of national styles of singing derive from language.2 As Andrea von Ramm has observed,

The characteristic sound of a language can be imitated as a typical sequence of vowels and consonants, as a melody, as a phrasing. There is an established rhythmical impulse of a language and a specific area of resonance involved for this particular character of a language or a dialect. In German one can say instead of ‘Dialekt’ also ‘Mundart.’…This causes a different sound, a different resonance and a different singing voice, depending on the language sung.3

Seventeenth-century writers on singing also recognized the importance of language. Christoph Bernhard discussed Mundart at some length in Von der Singe-Kunst oder Manier:

The first [aspect of a singer's observation of the text] consists in the correct pronunciation of the words…such that a singer not rattle [schnarren], lisp or otherwise exhibit bad diction. On the contrary, he ought to take pains to use a graceful and irreproachable pronunciation. And to be sure in his mother tongue, he should have the most elegant Mund-Arth, so that a German would not speak Swabian, Pomeranian, etc, but rather Misnian or a speech close to it, and an Italian would not speak Bolognese, Venetian or Lombard, but Florentine or Roman. If he must sing in something other than his mother tongue, however, then he must read that language at least as fluently [fertig] and correctly as someone born to it. As far as Latin is concerned, because it is pronounced differently in different countries, the singer is free to pronounce it as is customary in the place where he is singing.4

The importance of Mundart makes it essential to open the Pandora's box of historical pronunciations, which in their specifics are beyond the scope of this essay. While Italian (a language full of dialects) has changed little in its pronunciation in the last four centuries, French and English have changed profoundly. As a literary language, German was in its infancy in the seventeenth century; it did not achieve a standardized pronunciation for the theater until the late nineteenth century. Even the same language, such as Latin, was pronounced differently in different places (and still is). Research in historical pronunciations yields many revelations in the poetry and expands the palette of sounds available to the aural imagination.5

The singer's art was closely aligned with the orator's during the Baroque period. The clear and expressive delivery of a text involved not only proper diction and pronunciation, but also an understanding of the rhetorical structure of the text and an ability to communicate the passion and meaning of the words. How this was achieved differed according to the particular characteristics of the language and culture as well as the musical style. The swing of the pendulum between the primacy of the words and the primacy of the music that occurred during the seventeenth century is important to bear in mind as we survey singing in Italy, France, Germany, England, and Spain.

ITALY, CA. 1600-1680

During the 1580s and 1590s, florid singing in Italy reached a zenith with singers who excelled in the gorgia style of embellishments. These singers included women, boys, castratos, high and low natural male voices, and falsettists. The term gorgia (= throat) identified the locus of this technique, involving an intricate neuromuscular coordination of the glottis, which rapidly opens and closes while changing pitch or reiterating a single pitch, an action that is apparently innate to the human voice.6 A basic threshold of speed is required in order for throat articulation to work easily. The glottal action can be harder or softer depending on the degree of clarity and the emotional expression desired;7 the Italians apparently used a harder articulation than the French. In 1639 André Maugars observed that the Italians “perform their passages with more roughness, but today they are beginning to correct that.”8 Throat articulation works best when the vocal tract is relaxed and there is not excessive breath pressure.9

Lodovico Zacconi described gorgia singers as follows:

These persons, who have such quickness and ability to deliver a quantity of figure in tempo with such velocity, have so enhanced and made beautiful the songs that now whosoever does not sing like those singers gives little pleasure to his hearer, and few of such singers are held in esteem. This manner of singing, and these ornaments are called by the common people gorgia; this is nothing other than an aggregation or collection of many eighths and sixteenths gathered in any one measure. And it is of such nature that, because of the velocity into which so many notes are compressed, it is much better to learn by hearing it than by written examples. 10

In Italy, throat-articulation technique was often referred to as dispositione.11 There is ample evidence that it was carried over with the advent of monody and the new, more declamatory styles of singing, in spite of changes in ornamentation style and vocal technique. We find ornaments, such as the ribattuta di gola (“rebeating of the throat”), for example, whose very name suggests its performance technique. Giulio Caccini described the trillo, a repercussion on one pitch, as a “beating in the throat.”12

Learning a repercussion ornament was recognized as a good way to master throat articulation. Caccini remarks that the trillo and gruppo are “a step necessary unto many things.”13 It is in this context that we should understand Zacconi's remark that “the tremolo, that is, the trembling voice, is the true gate to enter the passages [passaggi] and to become proficient in the gorgia.”14 Equating Zacconi's tremolo with pitch-fluctuation vibrato, as some scholars have done, contradicts the nature of throat-articulation technique.15 I understand his reference to the continuous motion of the voice to refer to the rapid opening and closing of the glottis, which in the trillo is done continuously on one note. Learning this glottal action independent of changing pitch is enormously helpful as a first step, before advancing to passaggi and other ornaments involving rapid changes of pitch. As Zacconi says, it indeed “wonderfully facilitates the undertaking of passaggi.”16 It is impossible to use throat articulation and continuous vibrato simultaneously, because the two vocal mechanisms are in laryngeal conflict with each other. Because Zacconi's remarks so clearly refer to the gorgia style, it is highly unlikely that his tremolo signifies either pitch-fluctuation vibrato or intensity vibrato.17

The decision to use throat-articulation technique has a direct bearing on other stylistic decisions beyond the issue of vibrato. Because of the innate neuromuscular speed involved, the technical choice of throat articulation is directly linked to decisions regarding tempo. Given the fairly narrow physiological range of possible speeds, we can gauge the tempo range for pieces using throat articulated passaggi reasonably accurately.18

The declamatory style of singing developed by singer-composers such as Jacopo Peri and Caccini extended speech into song. It most likely involved a laryngeal setup known today as “speech mode,” in which the larynx is in a neutral position, with a relaxed vocal tract and without support from extrinsic muscles. Speech mode would have easily accommodated the continued use of throat articulation. What was new, compared to Renaissance practice, was the role (and style) of ornamentation in expressing the text and the use of a more flexible breath stream to reflect the increasing exploitat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Octave Designation Chart

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1. Vocal/Choral Issues

- Part 2. Wind, String, and Percussion Instruments

- Part 3. Performance Practice and Practical Considerations

- Part 4. The Seventeenth-Century Stage

- Appendix A. List of Names and Dates

- Appendix B. A Performer's Guide to Medieval Music: Contents

- Appendix C. A Performer's Guide to Renaissance Music: Contents

- Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index