![]()

ONE

Beijing’s Decision

MAO ZEDONG’S DECISION TO SEND CHINESE TROOPS INTO THE Korean War has been widely debated. Most Chinese military historians argue that Mao made a rational, correct, and necessary decision.1 China’s intervention secured its northeastern borders, strengthened Sino-Soviet relations, and saved the North Korean regime. China acted as a major military power for the first time since the First Opium War in 1839–42, against Great Britain. However, some historians in China, and many more in America, challenge this view and condemn Mao for gross misjudgments and an “idiosyncratic audacity” that cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers.2 Still others take a middle position and argue that Mao had few political alternatives in his effort to achieve full acceptance in the Communist world and to assume leadership of Asian Communist movements in the early 1950s.3 These scholarly efforts have laid a solid groundwork for a better understanding of the Chinese decision, yet the debate continues.

The examination of Beijing’s decision to enter the Korean War reveals a new Chinese strategic culture that advocated active defense to help the North Koreans win the ongoing civil war and to protect the newly established Communist state from a possible U.S. invasion. By July 1950 the situation in Korea was beginning to worry Mao.4 Between July 7 and July 22, Beijing mobilized forces in northeast China, or Manchuria, leading to an important strategic shift from defense toward intervention by early August. Military preparations accelerated through September, after Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Inchon (Inch’ōn) landing and the collapse of the NKPA, leading to serious debates in early October and culminating on October 4 in a final decision to commit Chinese troops to help North Korea. By October 19 the vanguard units of the PLA, which were among its best forces, had crossed the Yalu River and entered North Korea. The roles of Mao and the Party Center—which included the Central Committee, Central Military Commission, and National Congress of the CCP—represented unprecedented activism in the Korean War: China was no longer playing the role of a passive spectator, or an adjunct, in global power politics. This newly vigorous internationalism revealed a profound change taking place in Communist China.

Although external Cold War factors may appear to be the only motive behind this change, the crucial strategic shift came about for significant internal reasons. Modern Chinese history has demonstrated that neither foreign invasion nor the support of an international power could create a strong, centralized national government. Instead, the government’s power depended more on China’s political stability and military strength than on its foreign relations. In this sense, by entering the Korean War, it is possible that Mao saw a chance to continue the Communist movement at home and to increase China’s power abroad. Now that national security had been established by the Communists’ winning the last battle of the Chinese Civil War (1946–49) against the GMD on Taiwan, Mao’s strategic priorities were establishing the legitimacy the CCP needed as the ruling party, an economic recovery, and military modernization. His decision to enter the Korean War may also have been based on the PLA’s superiority in manpower, which made Mao and his generals overconfident in their ability to drive the UNF out of the Korean Peninsula.

“SOUTH HEAVY” AND AMPHIBIOUS PREPARATIONS

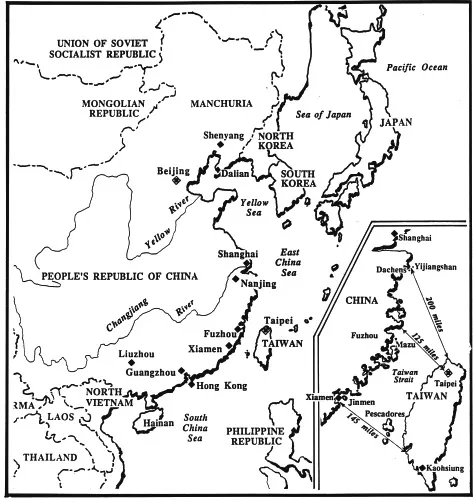

CCP leaders believed that Communist China had been founded, and could be maintained, by military power. By early 1950 China had the largest army in the world, totaling 5.4 million men. In contrast, U.S. armed forces had 1.5 million troops and the Soviet Union’s forces numbered 2.8 million, although they had grown to 4.8 million by 1953. After the defeat of the GMD, the PLA transformed itself from a “liberation army” into a national force with two new goals: to repel foreign invasions and to defeat internal threats to the new regime. Similarly, the Chinese government’s mission was to establish political order and national unity, to maintain domestic peace and tranquility, and to reorganize the military so as to be able to defend against foreign invasion. From this time forward, the PRC adopted an inward-looking governmental policy stressing national security and defensive military measures to consolidate and protect its territorial gains (map 1.1).

Map 1.1. China and Taiwan

The year before, however, Chinese leaders had still confronted over one million GMD troops in Taiwan (Formosa) and southwestern China. After the founding of the PRC on October 1, 1949, Mao’s first priority had been to consolidate the new state by eliminating all remnants of Jiang Jieshi’s GMD forces on Taiwan and other offshore islands.5 In late 1949 Jiang moved the seat of his government to Taiwan. At Taibei (Taipei), the new capital city of the ROC, Jiang prepared for the final showdown with Mao in the last battle of the Chinese Civil War. Jiang concentrated his troops on four major islands: 200,000 men on Taiwan, 100,000 on Hainan, 120,000 on the Zhoushan (Chou-shan) Island group, and 60,000 on Jinmen (Quemoy).6 Therefore, from October 1949 through June 1950, China’s military strategy was focused on its southern and coastal regions.

On October 31, 1949, in a telegram to Lin Biao (Lin Piao, 1906–71), then commander of the Fourth Field Army, Mao designed a “south heavy and north light” strategic plan for the PLA.7 Lin was one of the most brilliant military leaders of the CCP, becoming one of the ten marshals of the PLA in 1955 and defense minister of the PRC in 1959–71. His Fourth Field Army, the backbone of the PLA, defeated GMD forces from the north to the south in the Chinese Civil War. According to Mao’s post–civil war strategy for the four field armies, the “Third Field Army would defend Southeast China with a concentration in the Shanghai-Hangzhou (Hangchow)–Nanjing (Nanking) coastal region. Its main strength should prepare to take over Taiwan Island.” The Fourth Field Army should “station five of its armies in Guangdong (Kwangtung) and Guangxi (Kwangsi) as the southern defense force centered on Guangzhou (Canton), and deploy three armies along the railways in Central China as strategic reserve forces available to move either south or north.”8 Following Mao’s instructions, in late 1949 the Third Field Army, with one million troops in Southeast China, and the Fourth Field Army, with some 1.2 million troops in South China, were preparing for amphibious operations against the GMD-occupied islands to bring the Chinese Civil War to a close.9

In his “south heavy and north light” strategy of 1949, Mao considered Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Tianjin (Tientsin) as the three key points for national defense. Two of these points were in the south, where preparations for an amphibious attack on Taiwan were proceeding. In the meantime, Mao stationed three armies of the Fourth Field Army in central Henan (Honan) Province as strategic reserves. These armies would be transferred to the northeast in July–August 1950 and in October would become the first wave of Chinese forces to enter North Korea. In late 1949, however, Manchuria was not one of China’s key defense points, having only one infantry army, the Forty-Second, of the PLA’s fifty-seven infantry armies. Northeast China, which included the three provinces of Liaoning, Jilin (Kirin), and Heilongjiang (Heilungkiang) and shared borders with North Korea and the Soviet Union, had three artillery divisions, five local independent divisions, and one public security division, totaling 228,000 troops.10

In late 1949 the PLA high command followed Mao’s strategy by concentrating on landing preparations against the GMD-held islands along China’s southeastern coast. Mao, however, showed extra caution in this final battle in the Chinese Civil War against Jinmen and Taiwan because of a disastrous landing made by the Tenth Army Group of the Third Field Army on Jinmen, a small island group lying less than two miles off the mainland. The Twenty-Eighth Army of the Tenth Army Group had lost three infantry regiments, totaling 9,086 men, during an attempted landing on October 24 and 25, 1949.11 Mao asked his coastal army commanders to “guard against arrogance, avoid underestimating the enemy, and be well prepared.”12 In the meantime, Su Yu (1907–84), deputy commander of the Third Field Army, warned the high command that it would be “extremely difficult to operate a large-scale cross-ocean amphibious landing operation without air and sea control.”13 Su, one of the most experienced commanders of the PLA after Lin, commanded the Third Field Army and defeated GMD forces in eastern China in 1948–49. In 1955 Su was made one of the ten grand generals and became chief of the PLA general staff.14

To better prepare a PLA amphibious campaign, in December the high command reorganized the headquarters (HQ) of the Twelfth Army Group, Fourth Field Army, into the HQ of the PLA Navy. Xiao Jinguang (Hsiao Kin-kuang, 1903–89), commander of the Twelfth, was appointed the first commander of the PLA’s new navy.15 Xiao became vice minister of defense in 1954 and was promoted to grand general in 1955. It is important to note that at this time the Chinese forces were numerically and technologically inferior to GMD air and naval forces.16 That was partly why the Jinmen landing failed. Since the PLA had neither enough air power nor a modern navy, it would require Soviet aid.

MAO, STALIN, AND THE TAIWAN LANDING PLAN

Mao arrived in the Soviet Union on December 16, 1949, for a state visit, hoping to get the military assistance China desperately needed through an alliance between the PRC and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Stalin, however, was never an easy person for the Chinese to get along with, even though they were his Communist comrades. Frustrated after two fruitless meetings with Stalin in December, Mao was disturbed and annoyed that he was unable to meet with Stalin again for more than three weeks in January 1950.17 Nevertheless, during the sixtyfive days he spent in Moscow, Mao gained a better understanding of Stalin’s intentions. Among other things, Stalin wanted to convince Mao that the Soviet Union had its own difficulties. There would be no free ride for China, which should share the responsibility for the worldwide Communist movement. Stalin made it clear that China should support Communist movements in other Asian countries.18

Preoccupied with European affairs, Stalin needed Chinese help with ongoing Asian Communist revolutions: the First Indochina War in Vietnam and North Korea’s attempt at national unification. In addition, Stalin had no intention of challenging the Yalta agreement, which had been signed by the Soviet Union and the United States, that created a post-WWII international system and including the Soviet Union as one of the major powers. From 1946 to January 1950, Stalin was concerned that any change in the Yalta system might cause a direct conflict between the two superpowers. In his office, Stalin told Mao: “The victory of the Chinese revolution proved that China has become the center for the Asian revolution. We believe that it’s better for China to take the major responsibility in supporting and helping [Asian countries].”19

Stalin engaged the PRC in the Cold War both ideologically and geographically. Whether it was the symbolic significance of the Communist group that ideologically bound China to show its duty, or simple nationalistic interest, China was required to make at least some commitment to support the Soviets in the Cold War. Even though Mao was unhappy with Stalin’s demand, he understood the Soviet leader’s intention and agreed to share “the international responsibility.”20 Chen Jian points out that “in an agreement on ‘division of labor’ between the Chinese and Soviet Communists for waging the world revolution, they decided that while the Soviet Union would remain the center of international proletarian revolution, China’s primary duty would be the promotion of the ‘Eastern revolution.’”21

In February 1950 Mao and Zhou Enlai signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance with Stalin in Moscow.22 Zhou was political, diplomatic, and military leader of the PRC, serving as its premier in 1949–76 and foreign minister in 1949–58.23 Zhou’s most notable achievements were in the diplomatic realm. In his capacity as premier, he spent much of his time abroad, boosting the PRC’s international standing. His diplomatic approach to the world, especially to the Communist bloc in the Cold War, was flexible and pragmatic. The Sino–Soviet Treaty ensured Soviet military assistance if China was invaded by an imperialist power—which the Communists probably thought was most likely to be the United States or Japan.

From the moment that Communist China came into being, Beijing’s leaders regarded the United States as China’s primary enemy and, at the same time, consistently declared that a fundamental aim of the Chinese revolution was to destroy the old world order dominated by American imperialists.24 Through endless p...