![]()

1 “The Girl, Obviously, Was Asked to Be a Hero”

THE OPENING LINES of Hannah Arendt’s “Reflections on Little Rock” essay read: “It is unfortunate and even unjust (though hardly unjustified) that the events at Little Rock should have such an enormous echo in public opinion throughout the world” (RLR 46). Arendt goes on to situate these events inside the context of American slave history and outside the world politics of imperialism and colonialism. In her view, the one great crime that created a color problem in America was slavery, while the color problem in Europe was created by colonialism and imperialism.1 She asserts, “The country’s attitude toward the Negro population is rooted in American tradition and nothing else. The color question was created by the one great crime of American history and is soluble only within the political and historical framework of the Republic” (ibid.). It is fascinating to see Arendt casually describe discrimination toward African Americans here as an attitude rooted in tradition. But even more interesting is her acknowledgment that the color question was created by slavery and requires a solution within the political and historical framework of the United States. This suggests that a political solution is needed.

Despite opening the essay with the weight of the historical realities of slavery, race, racism, and the political consequences of these realities in the U.S. context, Arendt does not situate and analyze the color question in a “political and historical framework.” She chooses instead to characterize segregation, especially in education, as a social issue. Arendt presents the desegregation crisis in public education as a Negro problem (namely, a problem of Black parents seeking upward social mobility, like parvenus) rather than a white problem (specifically, the problem of white supremacy and anti-Black racism in the form of legally sanctioned racial segregation).

The Publication of “Reflections on Little Rock”

Written for Commentary in 1957, Hannah Arendt’s “Reflections on Little Rock” was steeped in controversy from the very beginning. Arendt explains that this essay did not get published at that time because her contentious viewpoint “was at variance with the magazine’s stand on matters of discrimination and segregation” (RLR 45).2 The gossip and consternation swirling around Arendt’s “Reflections on Little Rock” cannot be overstated. According to Norman Podhoretz, Arendt’s essay was deemed so controversial that Commentary did not want to publish it. The editors eventually offered a compromise that Commentary would publish her piece alongside a reply by Sidney Hook in the same issue. This was not typical, since replies were usually published in the issue that followed the essay of interest. After several delays, which in Arendt’s estimation allowed the proliferation of rumors about her position before it was even published, Arendt withdrew her article from Commentary.

Both Hook and Arendt published their essays elsewhere. Hook published his in the New Leader (April 21, 1958) under the title “Democracy and Desegregation.” Arendt’s somewhat tendentious reflections did not appear in print until 1959, when she agreed to allow Dissent to publish the original essay without revisions. Arendt explains that she did so in an effort to challenge “the routine repetition of liberal clichés [which] may be even more dangerous” than she initially thought (RLR 45). But Arendt’s often contested stance in “Reflections on Little Rock” proves to be as pernicious, if not more so, than the liberal clichés against which she wants to position herself. In addition to the “Preliminary Remarks” and the original essay, Dissent also included two critical replies to “Reflections” in the same issue. Arendt’s reply to her critics was published separately in a later issue of the magazine along with an angry letter from Hook, critiquing Arendt again, and a fiery response to Hook from Arendt.

“If You Look at the Picture the Right Way, You See What I See”

In “A Reply to Critics,”3 Arendt explains that a newspaper photograph of a “Negro girl” persecuted by white children while attempting to integrate a school prompted the writing of “Reflections on Little Rock.” She adds that her reflections unfolded around three questions: “What would I do if I were a Negro mother?,” “What would I do if I were a white mother in the South?,” and “What exactly distinguished the so-called Southern way of life from the American way of life with respect to the color question?” (Reply 179–181). When “Reflections on Little Rock” is read together with the “Preliminary Remarks” added to the original essay and her later “A Reply to Critics,” we find Arendt making several errors in judgment, coupled with factual errors. All of these mistakes have implications beyond the Little Rock crisis in particular and the intervention of the federal government in public school integration at the local level more generally.

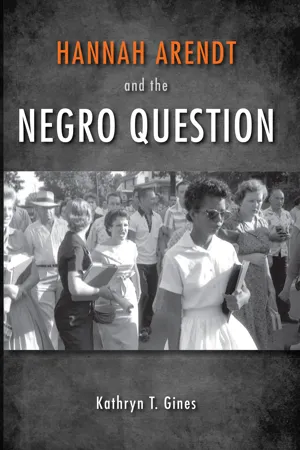

Let us begin with Arendt’s errors and assumptions about the photograph that is a primary point of interest in “Reflections.” Arendt describes it in the following way: “I think no one will find it easy to forget the photograph reproduced in newspapers and magazines throughout the country, showing a Negro girl, accompanied by a white friend of her father, walking away from school, persecuted and followed into bodily proximity by a jeering and grimacing mob of youngsters. The girl, obviously, was asked to be a hero—that is something neither her absent father nor the equally absent representatives of the NAACP felt called upon to be” (RLR 50). But Arendt is mistaken about the image, the friend, the father, and the NAACP representatives. Her point of departure for seeking to understand the situation is already steeped in multiple misunderstandings.

Danielle S. Allen notes in Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education that Arendt is referring to a front-page photograph in the New York Times on September 5, 1957.4 The newspaper’s front page on this date actually features two photographs pertaining to school desegregation. Each photograph includes a fifteen-year-old Black female student, and the young ladies are wearing similarly patterned dresses. The top image depicts the National Guard creating a barrier preventing Elizabeth Eckford from gaining access to Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, while a white female student is allowed to bypass the barrier.5 The bottom image shows Dorothy Counts and Dr. Edwin Thompkins surrounded by “jeering” white students while walking toward (not away from) Harding High School in Charlotte, North Carolina.6 Arendt mistakenly describes the photo of Counts in Charlotte rather than the one of Eckford in Little Rock. And her interpretation of the photograph and assessment of the scene are wrong in both cases.

Elizabeth Eckford, arriving at Central High School, initially thought that the National Guard was there to protect her. Eckford soon realized the soldiers were there (under orders from Arkansas governor Orval E. Faubus) to keep her out of the school rather than to protect her from the crowd. Unfortunately, Eckford did confront the angry, white, racist mob on her own in Little Rock. But this was due to a breakdown in communication, not neglect on the part of her parents or the NAACP, as suggested by Arendt. It should be stressed that NAACP representatives and the parents of the Little Rock Nine wanted to accompany their children to Central High School, but were explicitly instructed not to do so by Little Rock’s school superintendent, Virgil Blossom.7 Blossom’s rationale was that “if violence breaks out … it will be easier to protect the children if the adults aren’t there.”8 In spite of Blossom’s instructions, Daisy Bates, the president of the NAACP in the state of Arkansas, wanted some adult protection for the children. Bates asked a white minister, Rev. Dunbar Ogden, if he and other ministers would accompany the children and thereby prevent an attack from the expected angry white mob. Ogden told Bates that the white ministers were hesitant to do this. But Ogden and his twenty-one-year-old son, David, along with one other white minister (Rev. Will Campbell) and two Black ministers (Rev. Z. Z. Driver and Rev. Harry Bass) agreed to accompany the students.9

With this arrangement in place, the students were advised of a new plan to meet at a designated location before going together to the school by a late-night phone call from Bates. But Elizabeth Eckford and her parents were not aware of the change in plans because they did not have a telephone. This unfortunate break-down in communication led to Eckford’s fate: facing alone a racist white mob calling for her to be lynched, on one side, and National Guards pointing bayonets at her as she attempted to enter the school, on the other. Eckford later told Bates, “Somebody started yelling, ‘Lynch her! Lynch her!’ … They came closer, shouting, ‘No nigger bitch is going to get into our school. Get out of here.’ I turned back to the guards but their faces told me I wouldn’t get help from them.”10

When Eckford finally made it back through the mob and to a bus stop, Dr. Benjamin Fine, the education editor of the New York Times, sat beside her and put his arm around her. Fine is the author of the article “Arkansas Troops Bar Negro Pupils; Governor Defiant” that accompanies the photograph of Eckford in the New York Times. Fine does not mention his own consolation of Eckford, but does name Grace Lorch, described as “a white woman” who “walked over to comfort her.” Lorch is quoted in the article as saying to the angry mob, “She’s just a little girl…. Why don’t you calm down? … Six months from now you’ll be ashamed of what you’re doing.” Fine would later share his experience in the crowd with Bates: “Daisy, they spat in my face. They called me a ‘dirty Jew.’ I’ve been a marked man ever since the day Elizabeth tried to enter Central.”11 He continued, “A girl I had seen hustling in one of the local bars screamed, ‘A dirty New York Jew! Get him!’ A man asked me, ‘Are you a Jew?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He then said to the mob, ‘Let him be! We’ll take care of him later.’”12

While Elizabeth Eckford was one of nine students to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Dorothy Counts (the girl in the photograph Arendt actually describes) was the only Black student allowed to integrate Harding High School in Charlotte. Every other request by Black families to integrate this high school was denied by the school board. Dorothy’s father, Dr. Herbert Counts, and family friend Dr. Edwin Thompkins, both professors at John C. Smith University—a Presbyterian theological seminary—took Dorothy to school on the first day. Upon their arrival they found the roadway in front of the school, a path that was usually open, had been blocked off. Consequently, Dr. Thompkins walked with Dorothy to the school while Dr. Counts, very much present for his daughter, parked the car. Contrary to Arendt’s description, Dorothy’s father was not absent and Dr. Thompkins was not “a white friend of her father”—he is Black.

After school, Dr. R. A. Hawkins, a local dentist, NAACP activist, and another African American friend of Dr. Counts, walked Dorothy from the school to the car, where her father was again present and waiting. This scene after school is not depicted in the photograph, but is described in the accompanying article, “School Integration Begins in Charlotte with Near-Rioting” written by Clarence Dean. According to Dean, as Dorothy and Dr. Hawkins walked from Harding High School to the car, the white crowd threw water, paper cups, and sticks at them. At this, the local police “did not intervene,” but when the crowd tried to rock the car as Dorothy and Dr. Hawkins got in, “the police closed in firmly and cleared the crowd away.”13 Dean also mentions two other Black students integrating schools in Charlotte on that day, both accompanied by a parent: “Gustavas Allen Roberts, 16, was admitted to Central High School. His younger sister, Girvaud Lilly Roberts, 12, was enrolled at Piedmont Junior High School. The boy was accompanied by his father, a construction worker, and the girl by her mother.”14

Parts of this background information were not available to Arendt because some of the details provided here would not become available until decades after the events of 1957. However, other information was readily accessible, not only in the photographs themselves but also in the captions and articles printed with the photographs. In the specific example of Dorothy Counts, there is never a description of Dr. Thompkins as a white friend of her father. Arendt assumes that Thompkins is white.15 Also, Dean states in the same article that Dr. Hawkins (identified as a Negro dentist, but he was also a member of the NAACP) met Dorothy after school and they walked together to her father, who was waiting for her in a car. The article makes it clear that neither the NAACP nor the father were absent from the scene as Arendt claims.

It seems that the facts about the Counts family and their friends do not line up with Black families as they apparently existed in Arendt’s imagination. It did not occur to Arendt that Dr. Counts was valedictorian of his high school class before earning several degrees with honors.16 She did not imagine that Dorothy, who spent several weeks in summer camp in another state with a white room-mate to prepare to attend Harding High School, felt pity rather than fear walking through the crowds of angry white students. In The Dream Long Deferred: The Landmark Struggle for Desegregation in Charlotte, North Carolina, Frye Gaillard notes that Dorothy “walked through them calmly, feeling, she remembered later, a strange mix of emotions, though oddly enough, fear was not among them…. She felt pity for them … that they would not do these things if they had grown up in a family as loving as her own.”17 Dorothy later looked back on the situation with journalist Tommy Tomilson: “People say, ‘How did you let somebody spit on you? How did all those people say those things?’ I always say, if you look at the picture the right way, you see what I see. What I see is that all of those people are behind me. They did not have the courage to get up in my face.”18

How is it that Arendt’s interpretation of the photograph(s), the starting point for her reflections, is so wrong? Arendt does not see what Dorothy sees in the photograph. Arendt is not seeking understanding; rather, she thinks that she already understands. Arendt looks upon the photographs with already formed assumptions ...