![]()

History of the Discoveries of Dinosaurs and Mesozoic Reptiles in Mexico Jose Ruben Guzman-Gutierrez and Héctor E. Rivera-Sylva | 1 |

The Earliest Records

The oldest records for the discovery of prehistoric gigantic bones in what is today Mexico begins with the mythology of pre-Hispanic Aztecs who believed in the existence of giants they called “Quinametzin” or “Quinametin” (Maldonado-Köerdell, 1948; see also Mayor, 2005). Later, during the Spanish conquest, some documents chronicle the discovery of gigantic bones. One of these reports was by Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas (1549–1626), who wrote in 1615 about the “bones of giants” from what are today the Mexican states of Tlaxcala and Yucatán. He also wrote that Hernando Cortés shipped some of the bones to the king of Spain during the first years of the Spanish occupation (Herrera y Tordesillas, 1730; published posthumously).

In 1754, Jesuit father Fray Joseph Torrubia (1698–1761) wrote in his work on the natural history of Spain and its colonies that fossils (petrifactions, as they were called) were organic in origin, which was contrary to the then-accepted explanation of them as “games of Nature.” He also dissents about what he calls “Spanish Gigantology,” which documented the existence of a race of giants in both the Old and New Worlds (Torrubia, 1754). These bones were recognized as belonging to fossil elephants as early as 1795. The remains of extinct proboscidians were commonly found during the excavations for buildings and wells. Although Pleistocene and other Late Tertiary mammals are common throughout Mexico, we have no record of dinosaur bones being found at this early date (Anonymous, 1799). Additional fossils from Mexico were mentioned by Don Andrés Manuel del Río (1764–1849) in his “Elements of Orictognosy” [mineralogy] (Del Río, 1795). Del Rio was a Spanish mineralogist who had studied with Abraham Gottlob Werner and Antoine Lavoisier.

The first report about dinosaurs in Mexico turned out to be an error. In 1840, Wilhelm Mahlmann briefly mentioned the discovery by Carl Degenhardt (a German mining engineer and friend of Baron Alexander von Humboldt) of footprints belonging to “great birds” at Oiva, which was erroneously stated as being in Mexico, instead of Colombia (Mahlmann, 1840). This error has subsequently confused many workers, who have perpetuated the mistake (e.g., Winkler, 1886; Kuhn, 1963; Thulborn, 1990) and was only recently corrected (Buffetaut, 2000). French geologists M. M. Dollfus and E. de Montserrat of the Commission Scientifique du Mexique made the first authentic report of dinosaurs from Mexico. Their report on the geological reconnaissance of the mining district of Sultepec, now a municipality in the southern state of Mexico, makes reference to some “small saurian footprints”: “in the Barranca of Tisate, there is a whitish tuff, very fine, appearing to be perhaps silica. It is claimed that footprints of small saurians have been found in these tuffs, and we saw also the imprints of leaves and snails …” (Dollfus and Montserrat, 1867:479). This report essentially initiates the discipline of vertebrate paleontology in Mexico. About this time, Richard Owen, the creator of the “Dinosauria,” described the fossil horses from the Valley of Mexico and a fossil llama from Tequixquiac. However, he makes no mention of older vertebrate faunas.

In the mid-1880s, the American dinosaur hunter par excellence (along with his nemesis Charles Marsh) Edward Drinker Cope (1884, 1886) published on the extinct Mammalia of the Valley of Mexico and the Loup Fork Miocene in Mexico. He described Tertiary and Quaternary fossil mammals from the mining districts in the Valley of Mexico. However, he did not explore the Mesozoic strata that generally crop out in the northern part of the country, and so he missed the chance to find dinosaur remains.

In 1869, Mexican geologist Antonio del Castillo wrote his opus “Säugethierreste aus der Quartär-Formation des Hochthales von Mexico” which is a milestone in the history of Mexican vertebrate paleontology because it is the first paper written by a Mexican paleontologist (the previous publications were all written by European naturalists). In 1888, del Castillo was instrumental in founding the Geological Commission and the Instituto Geológico de México (the National Geological Institute of Mexico). Construction of the Instituto Geológico building was started on July 17, 1900. The building, which is now the Museum of Geology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, was the first building in Mexico designed to house the collections and laboratories of the institute. The façade of the building shows interesting decorative elements comprising high and bas-reliefs of fossil marine fauna, such as ammonites and ichthyosaurs, and of pterosaurs, a fossil vertebrate group that was not discovered in Mexico until recently (see chapter 8). The architect Carlos Herrera López and the geologist José Guadalupe Aguilera Serrano (1857–1941), then the Director of the Instituto Geológico, designed the façade. The building was dedicated on September 6, 1906, during the tenth International Geological Congress, held in Mexico City. Inside the magnificent building are ten large paintings by the great Mexican landscape artist and naturalist José María Velasco (1840–1912), representing the evolution of life through the geological ages, from its origin in the primeval seas to the appearance of humankind. Unfortunately, neither dinosaurs nor marine reptiles appear in any of them. By the turn of the twentieth century, a group of mostly European scientists began publishing on the fossils of Mexico in the institute’s two journals, the Instituto Geológico de México Boletín and Parergones del Instituto Geológico de México. However, nothing appeared on dinosaur fossils.

The Twentieth Century

The first dinosaur or marine reptile bone found in Mexico may have been found by José Guadalupe Aguilera Serrano, director of the Instituto Geológico de México from 1865 to 1912. The report of the discovery was made by Yale paleontologist George Reber Wieland (1865–1953), who wrote that Serrano “had previously found in Chihuahua a weathered vertebral centrum attributable to a ‘reptile’ from the beds equivalent to the American Pierre Formation” (Wieland, 1910:360). Unfortunately, Wieland does not specify whether this information is based on a publication or a personal communication from Serrano. It is impossible to track down this specimen to determine its identity. The Pierre Formation of the United States is a marine deposit, so the bone may well have belonged to some marine reptile instead of a dinosaur.

In 1921, the German geologist and paleontologist Wilhelm Freudenberg published his book about the geology of Mexico and provided the first record of dinosaur ichnites in Mexico. The locality was in the state of Chihuahua, near the city of Parral. As far as we are aware, historians of Mexican paleontology previously have always mentioned Werner Janensch’s 1926 report as the first published record of dinosaurs from Mexico, rather than Freudenberg’s report. Unfortunately, Freudenberg did not illustrate the specimen, nor can the slab with tracks be found at the Instituto Geológico de México, where it was sent. All that remains is Freudenberg’s (1921:122) description: “in 1907 the footprint of a dinosaur in a red sandy shale was found in Parral and was sent to the Instituto Geológico in México. Such tracks are common in the Laramie Formation of the Union.”

The first record of a marine reptile from Mexico appeared in a brief work by Wieland (1910), who described a new taxon, Plesiosaurus (= Polyptychodon) mexicanus, from Tlaxiaco, Oaxaca. The specimen consisted of a partial rostrum with teeth that Wieland recognized as the first plesiosaur from Mexico. The specimen was lost for many years but was located by María del Carmen Perrilliat through the suggestion of Héctor Rivera-Sylva in the collections of the Colección Nacional de Paleontología, Instituto de Geología of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The specimen was restudied by Marie-Céline Buchy (2008), who showed that it was of a thalattosuchian crocodile instead of a plesiosaur.

The first discovery of dinosaur skeletal remains in Coahuila was made by Erich Haarmann (Fig. 1.1), a German geologist traveling in northern Mexico in the early twentieth century. While making a geological reconnaissance of Coahuila state in September 1910 (in the midst of the Mexican revolutionary war), fossil bones (“Saurierreste”) were found in what he called “Soledad-Schichten,” which he correlates with the Laramie Formation of the western United States. The discovery was made northeast of Soledad, north of Hacienda de Movano, in a place known as Lomas de Buenavista, in the state of Coahuila. Haarmann reported: “Fossils are rare, silicified wood and vertebrate remains were found only in one place in the huge conglomerate. … I had to content myself with picking up the weathered pieces that were not usually pretty well preserved. Unfortunately, there were no teeth, which would facilitate a determination. Eventually, I sent the vertebrate bones to Mr. Henry Schroeder, who kindly took over their investigation and came to the conclusion that it is most probable that they belong to dinosaurs. For an exact identification, collecting more abundant and better material is of course required, but shortage of water in that area makes that difficult, and it is currently impossible because of the revolution. Nevertheless, I hope that one day it will be possible to excavate more material on a larger scale” (Haarmann, 1913:26).

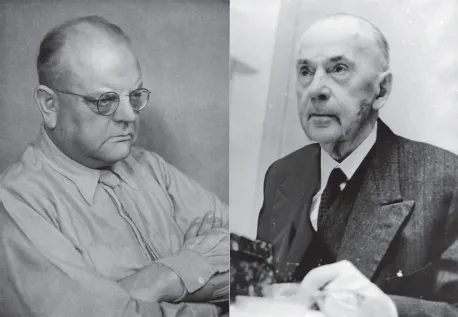

1.1. (Left) Erich Haarmann (1882–1945), German geologist who collected the first dinosaur bones in Mexico (from Geologische Rundschau, 1942). (Right) Werner Janensch (1878–1969), German paleontologist who published the first report on dinosaur fossils from Mexico. Courtesy of the Museum für Naturkunde der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Historische Bild- u. Schriftgutsammlungen (Sigel: MfN d. HUB, HBSB Bestand: Pal. Mus. Signatur: B I/69).

The fossils found by Haarmann were later transferred to the Geological and Palaeontological Institute and Museum of the University of Berlin and examined by Dr. Werner Janensch (1878–1969; Fig. 1.1) of Tendaguru fame. Janensch (1926) published a brief account of the discovery and described the few remains. The material consisted of (1) a large fragment of right squamosum, (2) a small caudal vertebral body, (3) a large section of a big limb bone (femur?), and (4) two indeterminate fragments. Janensch refers the material to a ceratopsian, probably to the genus Monoclonius (= Centrosaurus) or Triceratops. Re-examination of the bones suggests that they are hadrosaurian instead of ceratopsian (see chapter 10).

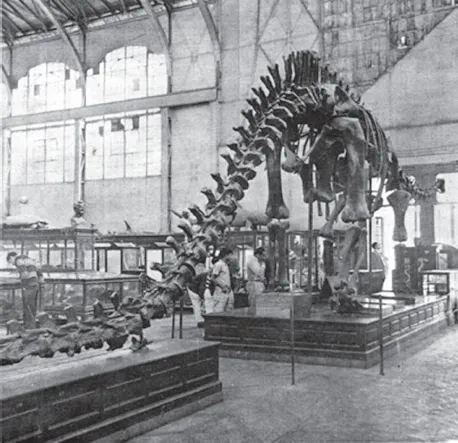

During the late 1920s, the great Mexican naturalist Alfonso L. Herrera (1868–1943) was director of the National Museum of Natural History in Mexico City, an institution founded in 1914. Herrera read in an important Spanish encyclopedia (Espasa-Calpe) that the steel entrepreneur and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie had made several replicas of the skeleton Diplodocus carnegii and had donated them to the most important natural history museums in the Western world. Herrera asked for a replica for his museum in Mexico City (Fig. 1.2) but mistakenly thought that the replicas were made of bronze, which he planned to position outdoors near the big lake of the botanical gardens of Chapultepec (Anonymous, 1928). His request was made through the ambassador of Mexico to the United States, Manuel Téllez. The ambassador made the formal petition to Carnegie, who liked the idea and turned the request over to William J. Holland (1848–1932), director of the Carnegie Museum. However, before the installation of the cast in the museum could be completed, Herrera resigned when control of the museum was transferred to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (Rea, 2001).

1.2. Cast of Diplodocus carnegii at the Museo de Historia Natural de la Ciudad de México as seen during the 1960s. This specimen was the first dinosaur mounted in Mexico (picture by Carlos López Campos, through the courtesy of the Museo de Historia Natural de la Ciudad de México).

While in Mexico City during the installation of the Diplodocus replica, Holland recalled seeing a dinosaur bone on exhibition at the National Museum of Natural History. He wrote, “I found in a corner of the museum among the paleontological material the femur of a small dinosaur found in the state of Chihuahua. There are Jurassic deposits in northern Mexico, and possibly elsewhere, and our Mexican friends may find on their own soil some of the huge dinosaurs of the Mesozoic age. Let us hope so” (Holland, 1930:86). Holland’s words have proven to be prophetic as seen by recent discoveries (see chapters 9 and 10).

The first known report of dinosaur fossil remains from Baja California was made in 1925. Bone fragments were collected in Cretaceous sediment outcrops some 160 miles south of the American-Mexican border. Unfortunately, it was not possible to identify them due to the fragmentary state of the bones (Morris, 1971).

M. G. Mehl, from the University of Missouri at Columbia, published on a new genus of mosasaur, Amphekepubis johnsoni. The specimen was discovered and collected by Carlyle D. Johnson from Upper Cretaceous concretionary clay cropping out from a locality about “forty miles east and a little north of Monterey [sic], in the state of Nuevo León, Mexico” (Mehl, 1930:384). The material consisted of nine presacral vertebrae, four of which were articulated; the right and left ilia; the left pubis and part of the right; the left ischium; the left femur; the right and left tibia; the left astragalus and part of the right; the left and right first metatarsal; and the base of the fourth digit and one complete phalanx, as well as parts of other small phalanges. Mehl mentions: “It is clear from the condition of the remains that a careful search would reveal other pieces of the specimen” (Mehl, 1930:384). Other mosasaur specimens were discovered by the German geologist and paleontologist Friedrich Karl Gustav Müllerried (1891–1952)—known during his stay in Mexico as Federico K. G. Müllerried. Müllerried (1931) recorded the discovery of two partial mosasaurs from a Late Cretaceous locality named Rayón. The site lay north of the Yamesí River, 60 km northwest of Tampico, Tamaulipas. The specimens were deposited in the National Museum of Natural History in Mexico City, but they are presently lost (Reynoso, 2006).

The American geologist Nicholas Lloyd Taliaferro (1890–1961), in his survey of Upper Cretaceous sediments in northern Sonora published in 1933, described the discovery of dinosaur remains: “in the upper part of the Snake Ridge Formation large dinosaur bones were found in greenish, sandy shales not more than 100 feet stratigraphically below the base of the Camas sandstone. Dinosaur bones and teeth were found in greatly baked, dark carbonaceous shales between two rhyolite sills in the gap between the Musteñas and Magallanes Peak. … These were...