![]()

1

HOW CAN THE SUBALTERN SPEAK?

Musical Style, Value, and the Historical Process of (Re)indigenization of Tamil Christian Music

People perform social identity through music. Thus musical value can encode both powerful and degraded social value. Over the last four hundred years, through multiple waves of culture contact and local internal negotiations, Tamil Christians have (re)indigenized Christian music, making conscious style changes in performance practice to encode shifts of power and social identity. Understanding the historical indigenization process of Tamil Christian music provides insight into how and why Theophilus Appavoo turned to folk music as his chosen medium for liberating theological production. It clarifies how he re-indigenized Christianity to the cultural resources of Dalit Christians in a context in which the devaluation of folk music paralleled the devaluation of outcaste people. The indigenization of Christian music in the Tamil context provides a model of the subaltern, re-sounding empowerment through theology in the church and greater society. Re-indigenization of Christianity to a Dalit theological identity through music is subaltern practice and praxis.

The first step to theorize subaltern musical practice is to recognize that the people who use and produce this music see it as meaningful. Tuning our ears to Dalit music forces the discipline of ethnomusicology to reconsider the valuation and power dynamics of our previous engagements with South Asian musical objects, subjects, and ideology. It necessitates deconstructing the illusion of value-free scholarship we have brought to the field in the last forty years through the almost singular study of classical practices in South Asia. Further, it provides an opportunity for greater dialogical engagement with those who create and use Dalit music in order to more fully understand its meaning in their lives. Deconstruction of disciplinary musical value in ethnomusicology through this case study of music as Dalit theology can provide theoretical perspectives for advocacy anthropology, specifically for Christian contexts, to understand the cultural process of production of theology. For the comparative field of history of religions this case shows the importance of musical processes in the study of the indigenization of religion. Finally, for Dalit historical studies it contributes a unique model of the ethnomusicological biography of a Dalit Christian culture broker.

MUSICAL INDIGENIZATION AMONG TAMIL CHRISTIANS

Christian indigenization occurs when individuals and communities interact under specific conditions of power to consciously choose and combine cultural characteristics that reflect, embody, and transmit the meaning of a Christian theological message through the cultural identity of the people who use it. Successful indigenization leads to a locally meaningful socio-spiritual experience for the indigenizers, or members of the identifying culture.1 The significance of the indigenization of Christian music as a potentially transformative tool lies in the correlation between the identity of the music and the cultural identity of those for whom Christianity is to change. Furthermore, when the tools of communication are in an accessible local medium the music is infused with indigenous meaning and power.

Tamil Christians have produced an array of indigenous Christian musics in various local styles and forms that reflect the social diversity of their community. That is, musical style references local Tamil social identities, especially of class, caste, and language. These identities in turn reference a dynamic of cultural exchange between various Christian mission societies and sub-communities of Tamil Protestants, as well as specific actors brokering the process of culture contact. Margaret Kartomi (1981, 232–233) defines “the complete cycle of positive musical processes set in motion by culture contact” as “musical transculturation,” but argues this term should be applied to “the processes of intercultural contact, not to the varying types of results” (ibid., 233–234). The application of Kartomi’s terminology in the Tamil Christian context leads to an analytical distinction between musical transculturation, and the variety of local manifestation of Tamil Christian musical indigenization, or results that have occurred from the sixteenth century to the present. Both the process and results involve extra-musical dynamics of power and value. Distinguishing between the two in analysis serves to differentiate colonial and elite domination from local indigenizing agency.

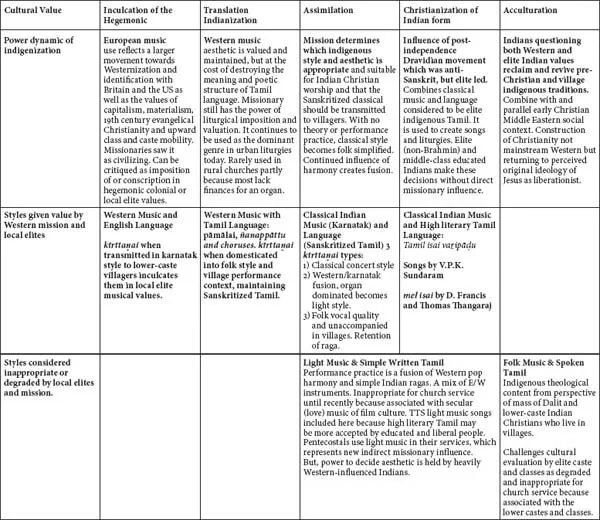

Table 1. Indigenization Taxonomy: Categories of Indigenization and Musical Style

Thus the ongoing process of the indigenization of Christian music over time in a single context can be continually transformative. T. M. Scruggs uses the term re-indigenization to describe a process of “renovation from within of an already established religion . . . [or] . . . a reinterpretation of important tenets within a single religion”2 (Scruggs 2005, 94). In the Tamil Christian context described below, liturgy is re-indigenized from karnatak classical music into the moods, language, and musical elements of Tamil folk music. In a few cases, we also observe that single texts of karnatak-style kīrttaṉai have been recomposed to Western, folk, or light music styles to articulate changes in the culture, social identity, and religious needs of Tamil Christians (Sherinian 2007a).

Steven Kaplan’s (1995, 10–23) model of Christian indigenization in Africa has been the most influential in ethnomusicology (see Scruggs 2005; Barz 2005; and Sherinian 2005). To understand the spectrum of indigenized Tamil Christian musics that have been created from 1606 to the present in Tamil Nadu I draw on Kaplan’s framework. This indigenization taxonomy goes beyond missionary initiation to delineate the balance of power within the social strata of the Tamil Christian community and between missionaries and Tamils as manifest through musical values. This results in a layered taxonomy that applies the indigenization categories to song styles and genres on the horizontal axis, yet considers the indigenization process that determines the cultural value of particular styles and those groups of people with whom the style is identified on the vertical axis. The vertical axis contains two divisions which refer specifically to the use of the particular style of indigenized music in a liturgical setting: styles given value by Western mission and local elites, labeled “appropriate,” and styles considered “inappropriate” or degraded by missionaries or local elites. The description of various types of Tamil Christian music below references this taxonomy to elucidate the power dynamics of indigenization and re-indigenization within the social and historical context of Tamil Christian music use (Table 1).

Tamil Christian music can be divided into three major groups: (1) English-language hymns and choruses using Western instrumentation; (2) pāmālai and ñanappāttu (Western hymns translated into Tamil while retaining the English or German tunes and meters); and (3) indigenous Christian music sung in some form of Tamil and using musical styles, poetical forms, and instrumentation that express culturally contextualized Christian hermeneutics. These indigenous styles include karnatak (classical or light classical), folk, and light music, the latter fusing Western pop with Indian folk and light classical music elements (Innasi 1994). Musical “style” as it references the category of indigenous Tamil Christian musics refers to an idiom (unit) of characteristic recognizable musical elements (or codes), performance procedures, and contextual purpose, use, and meaning.3 The musical codes are structural, functional, and rhetorical and cannot be separated from their contextual use and meaning, all of which are affected by the dynamic processes of performance and historical change.4 As a particular combination of clothing and physical behavior are commonly thought of as markers of social identity, I understand the combination of particular musical elements like rhythmic patterns, vocal timbre, instruments, and performance procedures (the structure of a style) as a musical package that is identified aurally as a musical style. As a functional device, musical style has a communicative presence, and as rhetoric it garners associations with particular subjects or ideas: here caste, class, denomination, and location. Thus the cultural arrangement of sound codes in this context I refer to as musical style identity.5

Next I elucidate how the three musical categories described above and the various musical style identities within them have been indigenized and re-in-digenized by Tamil Christians in the historical process of their social identity (re)formation. I analyze the type of indigenization that each musical style references within the indigenization taxonomy and the meanings each may simultaneously have for different subsections of the Tamil Christian community.

INDIGENIZED CHRISTIAN STYLES

English-language hymns and choruses using Western instrumentation are indigenized in Tamil Nadu only insofar as they have been adopted as symbols of class mobility, modernization, and Westernization by lower-caste Christians, particularly people of the Nadar caste who were converted by British Anglicans. The process of inculcation of Tamil Christians to the English language, British manners, and musical systems by the Anglican missionaries beginning in the 1820s eventually led to strong affinity for the organ and four-part harmony by many lower-caste Christians. Through adaptation of and association with this hegemonic colonial culture, lower-caste Nadars in particular hoped to gain status vis-à-vis local upper-caste/class elites (Brahmins and Vellalars).6 While identification with colonial powers is used to express agency against local elites (to claim equal or higher status with them), the category “inculcation in the hegemonic” implies a necessary complicity by lower castes both with missionary beliefs that their village goddess religion was “heathen,” and with the upper-caste ideology that village culture (folk music) was “degraded” (see Sherinian 2002). Yet, as stated above, this can also be an assertion of upward class mobility.

Complicity with the devaluation of folk culture and its association with socially and economically marginalized peoples have been the greatest challenge for Dalit liberation theology. Christians who have successfully raised their class status through identification with Westernized and local elite forms such as English hymns, and have attempted therefore to shed the stigma of untouchability, have been particularly resistant to the use of folk style, spoken language, or village cultural symbols in liturgy because of the negative associations of these cultural markers with their past identity. While those in this category make up the privileged top ten percent of the Dalit Christian population, the majority of Dalits still live in villages and have minimal ability to understand the English of these hymns.

Indigenization as translation is best represented in this context by the genres pāmālai and ñanappāttu. These are Western hymns translated in the early eighteenth century into sanskritized Tamil that retained their English or German tunes and meters. They reflect the restatement of Christian doctrine and terminology in local, although elite Brahmanical and literary Tamil, languages, and idioms (Kaplan 1995, 13–14). The Western music aesthetic of these genres is valued and maintained at the cost of rendering incomprehensible the meaning and poetic structure of the Tamil language. Furthermore, until the 1950s the missionaries retained the power to impose the use of, and imbue greater value upon, these genres over any other in formal Church liturgies and hymnals. In most urban Protestant church services today one will still commonly find that three of the four pieces sung are pāmālai. The continuing importance of these genres in urban churches can be attributed to the nostalgic association with the missionaries and Western values that these genres carry for middle-class Christians. As described above, alliance with these missionaries provided many outcaste Tamils opportunities for social and economic mobility (education and jobs) as well as the development of their self-esteem.

The introduction of indigenous karnatak music from Vaishnavite or Shaivite (Brahmanical Hindu sects) devotional practice into Tamil Christian worship illustrates the assimilation of local features to make the message of the Christian ritual more comprehensible and acceptable, particularly for upper-caste Indians (Kaplan 1995, 15–16). Catholic and Protestant missions from 1600 to the early 1900s encouraged the use of the karnatak style and genres in the sanskritized language of the caste/class elites as the favored local aesthetic for indigenous composition by converts. Approximately ten percent of the Protestant community is upper caste (mostly Vellalars or non-Brahmin landowners) who identify directly with this elite culture. As early as 1714 Christian kīrttaṉai by Vellalar converts were first printed under the supervision of German Lutherans to be used in their mission in Tranquebar and eventually Tanjore (Lehmann 1956). In 1853 the American Congregational missionary Edward Webb published a collection of over one hundred kīrttaṉai by the Vellalar Christian composer Vedanayakam Sastriar (1774–1864). After learning the kīrttaṉai directly from Sastriar in 1852, Webb and his Tamil catechists then disseminated the new Tamil hymnal to lower-caste villagers who lacked previous direct exposure to this elite cultural genre. Thus while the Christian kīrttaṉai represents “indigenization as assimilation” for upper-caste Christians, for the lower castes it was the means to inculcation in hegemonic Hindu cultural values. The transmission of Christian kīrttaṉai to non-elite people led by the missionaries reflects the conscription of these villagers into the musical values of the classical genres, particularly the previously inaccessible system of raga (melodic mode) and the linguistic system of manipravalam, sanskritized literary Tamil. Furthermore, today the meaning of the sanskritized Tamil texts of the kīrttaṉai is even less intelligible to most Tamils whose vernacular was purged of earlier Aryan influences through the Dravidian movement beginning in the 1940s.

Use of kīrttaṉai by the lower castes represents a two-tiered historical process of the indigenization (and re-indigenization) of Christianity.7 My analysis here considers the complexity of local social stratification that is essential to understanding the dynamics of indigenization of Christian music in south India. By the mid-twentieth century, kīrttaṉai experienced a process of musical “indigenization as translation” in some villages where lower castes began to accompany the words of kīrttaṉai with the stylistic idioms of folk melodies in similar modes, call and response forms, and rhythms. In urban areas kīrttaṉai went through a similar process of translation influenced by interest in Western harmony. Over the last 150 years the tunes for Christian kīrttaṉai have primarily been transmitted orally within communities that have had little access to classical karnatak music grammar. As a result, many kīrttaṉai have become simplified using only a skeleton of the original raga (lacking complex ornamentation or gamaka), and through using the Western tempered tuning system (major and minor modes) particularly with the introduction of harmonic accompaniment on the organ since the 1940s. Through such a “folk music strategy” of simplification in urban churches, ironically the kīrttaṉai have gradually been Westernized using simple diachronic melodies instead of karnatak modes. One could argue that this is musical re-indigenization for accessibility. On the other hand the sanskritized lyrics of the kīrttaṉai have remained codified and unchangeable for most Tamil Christians.8 Thus Christian kīrttaṉai lyrics contain very little theological meaning to most Tamils beyond their symbolic (superior) value as a “Christian karnatak tradition.”

After Indian independence and the formation of the Church of South India in 1947, Tamil theologians and composers began to combine elements of

Tami Icai (Tamil karnatak music) and desanskritized or

sen (pure literary) Tamil to create socially conscious indigenized songs and liturgies.

9 Many of these theologians (of the generation just before Appavoo) were influenced by the anti-caste, anti-Brahmin, and anti-Hindi ideology of the Dravidian movement that attempted to raise the status of Tamil culture and literary...