- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

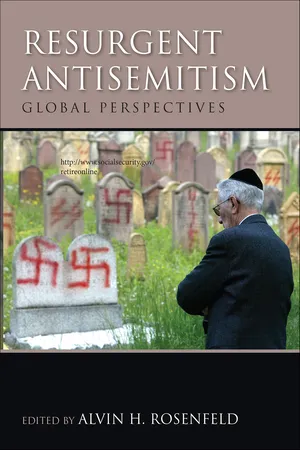

Dating back millennia, antisemitism has been called "the longest hatred." Thought to be vanquished after the horrors of the Holocaust, in recent decades it has once again become a disturbing presence in many parts of the world. Resurgent Antisemitism presents original research that elucidates the social, intellectual, and ideological roots of the "new" antisemitism and the place it has come to occupy in the public sphere. By exploring the sources, goals, and consequences of today's antisemitism and its relationship to the past, the book contributes to an understanding of this phenomenon that may help diminish its appeal and mitigate its more harmful effects.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Anti-Zionism, Antisemitism, and the Rhetorical Manipulation of Reality

Mal nommer les choses, volontairement ou pas, c’est ajouter au malheur du monde.

—ALBERT CAMUS

I

Over the past decade or so, in the Western world, it has become customary, on university campuses, in certain sections of the media, and among a diverse collection of “public intellectuals,” to argue, in the name of something called “anti-Zionism,” that Israel is an “illegitimate” state: a state that should never have been allowed to come into existence in the first place and whose continued existence is to be condemned as morally and politically intolerable.

It has become equally commonplace for those holding such views to be accused of propounding a “New” antisemitism, or at the very least of creating a climate of opinion favorable to the marked rise in antisemitic attacks in Western countries since the end of the 1990s.

Those charges have provoked a number of standard rebuttals, which characteristically include one or more of the following:

1. If there has been a resurgence in antisemitism in the West, and in the Islamic world, it is entirely occasioned by justifiable indignation at the conduct and policies of Israel.

2. The “Israel Lobby” and its tools allege antisemitism on the part of anti-Zionists for purely political reasons, as part of a campaign to discredit and silence progressive voices by branding “all criticism of Israel” antisemitic.

3. Anti-Zionism, by its nature, cannot be antisemitic, since it consists in opposition to Zionism, not in opposition to Jews or to Judaism per se.

The resulting exchanges tend to have the character of dialogues of the deaf: both sides burn with moral indignation, but neither side moves an inch beyond its original stance of accusation or rebuttal.

Can any light be shed on the rights and wrongs of this acrimonious debate? One obvious and immediate thought is that criticism of Israel, if by that is meant one or another rationally and empirically well-grounded objection to the conduct of this or that government of the State of Israel, cannot, in the nature of things, be antisemitic. Antisemitism is, by definition, a form of prejudice. Prejudice is hostility based upon falsehoods or faulty reasoning. It is not, as Catherine Chatterley, director of the Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, has recently put it,1 “a form of normal human hostility or even a function of normal human outrage, both of which are inevitable human reactions to war and conflict.”

At first sight, that thought appears to give game, set, and match to the “anti-Zionists.” Critics of Israel cannot, to the extent that their criticisms are factually well founded and soundly reasoned, be antisemites.

On the other hand, the same thought is fatal not just to one but to two of the standard rebuttals I mentioned a moment ago.

Take the second, for example. This alleges that accusations of antisemitism represent merely an attempt to silence critics of Israel by smearing “all criticism of Israel” as antisemitic. Given the deafening daily chorus of opposition to Israel to be encountered every day in the media and on the blogosphere, one thing to be said is that if that were the goal intended by these accusations, they have proved remarkably ineffectual in advancing it. But does it even make sense to allege that that is the intended goal? Criticism of Israel cannot, all agree, be antisemitic to the extent that it is factually well founded and soundly reasoned. Hence, who but a complete fool would wish to contend that “all” or “any” criticism of Israel is, by the mere fact of being critical of Israel, antisemitic? It follows that, unless those advancing such accusations are one and all complete fools—and manifestly, I would have thought, they are not—the attempted rebuttal fails.

Or take the first. This alleges that if there has been a resurgence in antisemitism in the West, and in the Islamic world, it is entirely occasioned by justifiable indignation at the conduct and policies of Israel. The difficulty for this line of rebuttal enters with the word “justifiable.” By definition, justifiable indignation is indignation aroused by factually well-based and soundly reasoned criticism of its object. It follows that, if factually well-grounded and soundly reasoned criticism of Israel cannot by definition be antisemitic, then neither is any indignation it may arouse. Hence it follows, that if a rise in antisemitism can be shown to have occurred, the proposed explanation is intrinsically incapable of explaining it.

So how are we to explain the widespread conviction, among many not unintelligent people, that current anti-Zionist polemic has more than an edge of antisemitism to it?

That question might be supposed to be still further darkened by the fact that virtually all those in the “anti-Zionist” camp at present regard themselves, and wish to be regarded, as principled “antiracists.” But light begins to dawn, it seems to me, at precisely this point.

Anti-Zionists are evidently justified in presenting themselves as anti-racists if Zionism itself is a form of racism. According to a notorious UN resolution of 1975, it is, and the equation of Zionism with racism continues to figure, explicitly or tacitly, in much anti-Zionist writing. The 1975 resolution was repealed in 1991, being by then widely recognized as pernicious. It is certainly absurd. Zionism is a form of nationalism. Only if all nationalism is racist per se can one argue that Zionism, as a form of nationalism, is intrinsically racist. But, manifestly, not all nationalism is racist. Any demand by a nation to exercise sovereign control over its own affairs is nationalist. That demand has been enforced by successful war in the case of Irish nationalism, and remains unsatisfied in the cases, for instance, of Kurdish or Basque nationalism. It remains quite unclear, however, why Irish or Kurdish or Basque nationalism should be regarded as “racist”; and if the Kurds, the Basques, and the Irish escape having this fashionable albatross hung around their necks, why not the Jews?

In any event, and whether or not Zionism is a form of racism, most anti-Zionists are opposed to racism as the notion of racism is normally understood. Does it follow that they are, therefore, necessarily opposed to, and therefore incapable of disseminating, antisemitism?

Plainly, that conclusion could follow only if the totality of phenomena ordinarily taken to constitute racism embraces the totality of phenomena ordinarily taken to constitute antisemitism—or to put it less pedantically, if antisemitism is no more than a special case, a mere variant, of racism as that is conventionally understood. And that requirement, it seems to me, is not met. That is to say, antisemitism is not just a form of racism, at least in the sense usually attached to the latter notion. Some of its manifestations are indeed manifestations of “racism” in the sense usually given to the word. But others are not. Antisemitism, though it does at times overlap with racism as that is usually defined, manifests a number of aspects that fall outside it, and cannot be understood in the same terms: aspects deeply bizarre and entirely sui generis.

If someone is insensitive to the aspects of antisemitism that distinguish it from racism as generally comprehended, that, in fact, render it sui generis as a form of prejudice, then of course, it will be entirely possible in principle for that person to be resolutely opposed to racism, but nevertheless lax, or entirely ineffectual, in his or her opposition to antisemitism. And that seems to me to be the case, sadly, with many current promoters of “anti-Zionism.”

Let us look more closely both at the areas of overlap between the notions of racism and antisemitism and at the areas where they part company: where the facts of antisemitism overflow the limits of the notion of racism as ordinarily understood.

II

At some point during the six decades that separate us from the end of the Second World War (my own memory locates that point somewhere in the 1960s), people stopped talking about “racial prejudice” and started talking about “racism.” The latter form came to be preferred mainly because it gave voice to a growing sense that prejudice, whatever its ostensible object, is always the same thing: the same in its nature and the same in its causes. The “ism” locution appeals because it gives one a way of writing that presumption into the very structure of the language one uses to describe this supposedly homogeneous phenomenon: “racism,” “sexism,” “ageism,” “elitism,” and so on.

The underlying thought motivating this particular linguistic shift is that the essence of prejudice is exclusion, operating always to maintain the power of a certain favored group. “Racism” works to sustain white power structures by excluding brown and black people, “sexism” sustains male power structures by excluding women, “ageism” favors the power of the middle-aged by excluding the elderly, “elitism” excludes those who fail to meet the putatively arbitrary “standards” that define cultural elites, and so on. This simple thought gives us both an explanation of why prejudice should exist at all and an explanation of why it is right to oppose it. Prejudice exists because there exists a rational motive for people to be prejudiced: namely, the maintenance of “power structures.” Prejudice should be opposed, not, or not primarily, because it promotes injustice, but rather because it promotes exclusion: the hiving off from “society,” as second-class citizens, of members of devalued social groups, whether so constituted by race, sex, age, class, or perceived educational inferiority.

The “ism” locution, in short, works to enshrine, at the heart of the very language we nowadays use in describing prejudice, a certain analysis, specific and, as we shall see, contestable, both of the nature and causes of prejudice and of the nature of the moral objections to it. It is an analysis that derives its moral credentials from the Enlightenment—specifically Rousseauian—ideal of a society without class distinctions of any kind. A just society, according to Rousseau, is one in which each citizen can look every other in the eye and say, truthfully, that he desires nothing that will disadvantage that Other. This cannot be the case in a society that is not homogenous; in a society divided into interest groups, “partial societies” (Rousseau’s term is société partielle), loyalty to which can easily divert the citizen from what should be his primary, and indeed sole, loyalty: loyalty to the General Will. Hence it cannot be the case in a society from which any group of citizens is excluded on account of the rest despising them as unworthy or inadequate. What is wrong with prejudice, then, according to the analysis we are considering, goes deeper, is more political in character, than any injustice it might inflict upon this or that individual. It is that, by promoting group exclusion, prejudice of any kind stands in the way of the achievement of a perfectly classless, and hence perfectly just, society.

The result of this shift in our speaking and thinking is that many, perhaps most, educated people tend to see antisemitism as just one more form of “racism.” They consider it morally akin to other forms of racism (and indeed to sexism, ageism, and elitism) in that, by stigmatizing Jews as Other and inferior, it endeavors to exclude them from full, and fully participatory, membership in society. This assimilation of antisemitism to “racism” has several consequences. First of all, it fosters the comfortable conclusion that, if that is what antisemitism is, there isn’t much of it around these days, at least in Europe and America. Nobody, nowadays, gets away with excluding Jews from hotels or social clubs. Nobody gets away, at least if they are discovered doing it, with operating a numerus clausus in education or the professions. That in turn fosters the rather widespread belief that antisemitism “belongs to the past,” is “no longer a problem,” and that, therefore, Jews who continue to complain and raise the alarm about it can only be doing so for more or less sinister political reasons.

Secondly, the belief that “racism”—and thus antisemitism construed as a variety of “racism”—is all about, and only about, exclusion, tends to drive a wedge between Jews and other victims of prejudice, in a way that is felt to give them less of a claim than others on the sympathies of “anti-racists.” For is not Judaism itself marked, in the perception of many non-Jews, not by the putatively generous universalism of both Christianity and the Enlightenment, but by an exclusiveness entirely of its own creation, deriving from the self-understanding of an observant Jew as a member of a “chosen people”? Have not Jews, precisely in consequence of the crabbed particularism of their religion, always gone to considerable lengths to refuse the choice of assimilation, of their disappearance, both as a separate “race” and as a species of société partielle exercising special claims on the loyalty of its members, into the general body of society: a choice held out to them as an enlightened alternative, ever since the French Revolution, by a long succession of progressive voices beginning with those of Voltaire and Clermont-Tonnerre? So do we not have to admit, in all honesty, as “sincere antiracists,” opposed to all forms of exclusion, that the Jews have been very much the architects of their own exclusion? And must not that admission force us to grant, equally, if antisemitism is indeed merely one more form of “racism,” that the Jews have themselves, to a great extent, been the architects of antisemitism?

The third consequence of the general presumption that antisemitism is just one more variety of “racism,” racism being understood as, essentially, hostility to the idea of an inclusive society, is one whose possibility we have already considered: namely, that it makes it very difficult, if not impossible, for a “sincere antiracist” to entertain the possibility that he or she might, somehow, be speaking or acting in antisemitic ways. After all, the sincere antiracist in no way wishes to exclude or stigmatize the Jews, but rather to welcome them into the ranks of progressive, forward-looking people, of all creeds and colors. From his—or her—point of view it is the Jews themselves, or rather the more conservative among them, who not only refuse any such offer, but do so out of considerations, be they Judaic or Zionist, which seem to him, precisely because they manifest an obstinate preference for separateness and self-determination over “inclusion,” to be themselves quasi-“racist” in the sense that most people nowadays give to the term. From his (or her) point of view, therefore, any accusation of antisemitism must appear merely factitious, or politically motivated, or both.

These consequences can be avoided in one’s thinking only when one begins to grasp that antisemitism, while in some of its forms equivalent to “racism,” in others vastly oversteps the conceptual boundaries of that category, as usually understood.

III

Most of what we call “racism,” “ageism,” “sexism,” and so on, I would prefer to call “social prejudice.” Social prejudice does indeed seek the exclusion from society (or “decent society”) of members of groups it despises, and seeks to achieve that aim through the dissemination of contemptuous stereotypes. According to such stereotypes, for example, Scots are sanctimonious and incorrigibly mean, women (as Virginia Woolf makes the uneasily male chauvinist young Cambridge don Charles Tansley insist in To the Lighthouse) “can’t write,” money has a way of sticking to Jewish fingers, West Indians are stupid and lead noisy, disorganized lives. T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Resurgent Antisemitism

- Introduction \ Alvin H. Rosenfeld

- 1. Anti-Zionism, Antisemitism, and the Rhetorical Manipulation of Reality \ Bernard Harrison

- 2. Antisemitism and Anti-Zionism as a Moral Question \ Elhanan Yakira

- 3. Manifestations of Antisemitism in British Intellectual and Cultural Life \ Paul Bogdanor

- 4. Between Old and New Antisemitism: The Image of Jews in Present-day Spain \ Alejandro Baer

- 5. Antisemitism Redux: On Literary and Theoretical Perversions \ Bruno Chaouat

- 6. Anti-Zionism and the Resurgence of Antisemitism in Norway \ Eirik Eiglad

- 7. Antisemitism Redivivus: The Rising Ghosts of a Calamitous Inheritance in Hungary and Romania \ Szilvia Peremiczky

- 8. Comparative and Competitive Victimization in the Post-Communist Sphere \ Zvi Gitelman

- 9. The Catholic Church, Radio Maryja, and the Question of Antisemitism in Poland \ Anna Sommer Schneider

- 10. Antisemitism among Young European Muslims \ Gunther Jikeli

- 11. The Banalization of Hate: Antisemitism in Contemporary Turkey \ Rifat N. Bali

- 12. Antisemitism’s Permutations in the Islamic Republic of Iran \ Jamsheed K. Choksy

- 13. The Israeli Scene: Political Criticism and the Politics of Anti-Zionism \ Ilan Avisar

- 14. The Roots of Antisemitism in the Middle East: New Debates \ Matthias Küntzel

- 15. Anti-Zionist Connections: Communism, Radical Islam, and the Left \ Robert S. Wistrich

- 16. Present-day Antisemitism and the Centrality of the Jewish Alibi \ Emanuele Ottolenghi

- 17. Holocaust Denial and the Image of the Jew, or: “They Boycott Auschwitz as an Israeli Product” \ Dina Porat

- 18. Identity Politics, the Pursuit of Social Justice, and the Rise of Campus Antisemitism: A Case Study \ Tammi Rossman-Benjamin

- 19. The End of the Holocaust and the Beginnings of a New Antisemitism \ Alvin H. Rosenfeld

- List of Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Resurgent Antisemitism by Alvin H. Rosenfeld in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Jewish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.