- 504 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

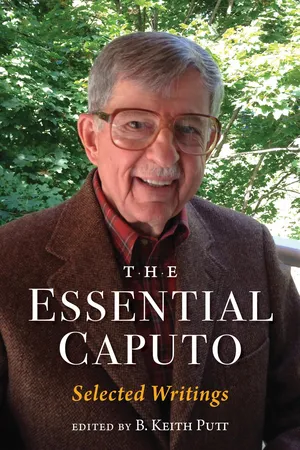

This landmark collection features selected writings by John D. Caputo, one of the most creative and influential thinkers working in the philosophy of religion today. B Keith Putt presents 21 of Caputo's most significant contributions from his distinguished 40-year career. Putt's thoughtful editing and arrangement highlights how Caputo's multidimensional thought has evolved from radical hermeneutics to radical theology. A guiding introduction situates Caputo's corpus within the context of debates in the Continental philosophy of religion and exclusive interview with him adds valuable information about his own views of his work.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Radical Hermeneutics: Reflections

1

The Repetition of Sacred Anarchy: Risking a Reading of Radical Hermeneutics

In February 1990, a good friend and I decided to journey to Conception Seminary in northwest Missouri in order to attend a conference on Catholic philosophy and deconstruction. Little did I realize how consequential those three days at that Benedictine monastery would be for me, personally and professionally. It was there and then that I first met and began to read John D. (Jack) Caputo. Jack initiated the weekend conference by delivering the first keynote address, a lecture entitled “Sacred Anarchy: Fragments of a Postmodern Ethics.” Although I did not know it at the time, I later realized that the essay actually reprises various significant themes that he first articulates in the final chapter of his 1987 book, Radical Hermeneutics, themes that continue to direct his thought decades later. For example, “Sacred Anarchy” offers another commentary on his distinction between responsible postmodernism and irresponsible postmodernism, a distinction that comes in tandem with the tension that develops when the religious perspective confronts the tragic perspective with reference to the issue of suffering.1 In Radical Hermeneutics, he raises the issue of how the religious perspective on suffering evokes a certain theology, a certain way of talking about God as always siding with those who suffer, with the victims of oppression, hunger, injustice, and disregard. For him, responsible postmodernism adopts the religious perspective and embraces, in one way or another and in one vocabulary or another, the theological position of joining God in the desire to alleviate the suffering of wounded flesh. This religio-theological sensitivity to the problem of suffering constitutes part of the mystery of existence—with “mystery” functioning as a legislating theme in that final chapter.

Just a year after the publication of Radical Hermeneutics, in the 1988 essay “Beyond Aestheticism: Derrida’s Responsible Anarchy” (chapter 11 in this reader), Jack obviously transfers the adjective “responsible” from qualifying “postmodernism” to qualifying “anarchy” in order to maintain the ethical dynamic of his thought while simultaneously acknowledging the necessity for avoiding the hierarchical closure of any ersatz rational absolute. Then, two years later, “responsible” is itself replaced with “sacred” in the lecture “Sacred Anarchy,” in which Jack amplifies aspects of “Beyond Aestheticism” and carries the themes of religion, suffering, God, and ethical responsibility into new directions. First, instead of contrasting responsible, religious postmodernism with irresponsible, tragic postmodernism, he writes as something of a contemporary Matthew Arnold and distinguishes between a Hebraic approach and a Hellenistic approach.2 The latter approach he identifies with Martin Heidegger, who tends to write rather elitist texts about Greek temples and strong bodies; consequently, there appears to be little Heideggerian attention paid to the weakness of flesh and to the vulnerability of suffering. In contradistinction to this inattention, the Hebraic, or Jewish, perspective focuses significantly on the issue of the vulnerability of flesh—that is, that which can be wounded, torn, subjected to death, but also that which can be vulnerable to therapy, to healing, and to renewed life. Eventually, Jack personifies the Jewish perspective in a particular individual who is not quite Jewish and not quite Christian, someone whom he names Yeshua, preferring his Aramaic name to the more typical Christian name, Jesus. He contends that Yeshua reveals a certain ethical sensitivity to the weakness of flesh and to the need for the alleviation of suffering. In his declarations, his deeds, and even in his death, Yeshua manifests a morality that Jack terms an “ethics of the cross.” In other words, Jack moves from the more general categories of mystery and God to a more specific analysis of the “sacred” under the factical rubric of Christianity.

Quite surprisingly, at least to me, Jack never published the complete text of “Sacred Anarchy: Fragments of a Postmodern Ethics.” Of course, one may find brief references to the text in various publications, such as the 1993 volume entitled Against Ethics, where it makes up the substance of one of Magdalena de la Cruz’s philosophical-lyrical discourses. Furthermore, one finds certain aspects of its content in Caputo’s 1997 work The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida. Still, the phrase “sacred anarchy” itself does not appear overtly in either book. That is not the case a decade later if one examines what could be called Caputo’s “discovered trilogy.”3 Both the content of the keynote address and its title are found throughout The Weakness of God (2006), The Insistence of God (2013), and The Folly of God (2015). Both are also central to What Would Jesus Deconstruct? (2007) and Hoping Against Hope (2015). One might correctly claim, therefore, that all of these major works are creative extrapolations of what Jack lays out in nuce in “Sacred Anarchy.” If so, then that keynote address may well be considered a textual synecdoche that encapsulates the primary motifs of Jack’s literary production. I certainly interpret the essay as a uniquely compelling work for comprehending the nuances of Jack’s thought over the past four decades. Not surprisingly, then, “Sacred Anarchy: Fragments of a Postmodern Ethics” has now been published as the fifteenth selection in the group of radical readings that compose this Caputo reader. I simply could not envision a Caputo reader without it.

THE POETICS OF RADICAL HERMENEUTICS

If you are reading this sentence, then you are, indeed, reading a Caputo reader—with “Caputo reader” functioning as a decidedly polysemic nominal phrase. Obviously, if you took the time to scan the table of contents before you turned to this introductory chapter, you would recognize the first meaning inherent in that overdetermined expression. This book is, indeed, a “Caputo reader” in the sense that it incorporates into one volume twenty-one full or partial texts—that is, “readings”—from the rather vast Caputoan corpus. The publication lying open before you may, therefore, be considered an anthology of selected works authored by Jack over a period of four decades, an anthology offering an easy guide for getting a “read” on his multidimensional philosophy. As an anthology, it collects or gathers together a representative assortment of texts that exemplify the continuities and discontinuities marking the evolution of various philosophical perspectives that he has typically denominated as “radical hermeneutics.”

“Anthology” certainly operates here as an appropriate synonym for “reader,” given that the term derives from the Greek anthologia, which literally means a “gathering of flowers,” or a “bouquet.” Quite often, the term refers bibliographically to a collection of “literary” flowers, that is to say, poems. Of course, Jack does not write poetry, at least not in the typical senses of that genre. Yet, if you do continue on and read some of the selections collected in this volume, you will discover, perhaps unexpectedly, that he does, indeed, write as a “poet.” He creates (in the Greek, poiein) what he calls various “poetics”—ranging, for example, from the “poetics of obligation”4 in 1993 to the “poetics of God” or “theopoetics”5 in 2015. Scattered across the two decades separating those two expressions of poetics one may also find the “poetics of the impossible,”6 the “poetics of the event,”7 the “poetics of the cosmos” or “cosmopoetics,”8 and the “poetics of the kingdom,”9 just to name a few. Ironically, one might well conclude, after a broader reading of Caputo, that all of these “poetics” manifest various perspectives on what I would call a “poetics of the rose.” Jack has consistently been a “cherubinic wanderer” preferring roses as the primary blossoms in his philosophical anthologias, specifically because they bloom ohne warum, sans pourquoi, “without why,” thereby calling for a certain Gelassenheit, or “letting-be,” that avoids the princely demands of the Principle of Sufficient Reason.10 For this reason, he has developed his own unique philosophically poetic or poetically philosophical voice in order to speak constantly from and at the limits of metaphysical reason alone.11

Of course, one might infer from his article “Demythologizing Heidegger: Alētheia and the History of Being” (chapter 7 in this reader) that Jack’s dismissal of the pretentious claims made by any recital of epic plots about definitive movements of capitalized words, such as Being, Spirit, Truth, Providence, or Destiny, manifests a genuine disdain for muthos, for the efficacy of narrative, or the poetic, or any symbolic genres of discourse. But such an inference would simply be mistaken. Jack only criticizes literary attempts that arrogantly presume to establish metanarratives privileging the one over the many, subsuming the plurality of subplots under some grand totalizing yarn that seeks to weave together a unified pattern having no loose ends. He believes, to the contrary, that a genuine poetics will emphasize the limits of such closed systems of thought, accentuate the porous nature of rational discourse, and celebrate the competitive profusion of multiple stories that demand the repetition of hermeneutics,12 with “repetition,” according to “Hermeneutics as the Recovery of Man” (chapter 8 in this reader) being a transformative asymptotic process of creative meaning.13 He summarizes this position quite well in a recent expression of his “poetics” manifesto: “We defer all absolute knowledge, absolute concepts, absolute spirits; we call for adjourning the meeting of the Department of Absolute Knowledge, sine die. In the place of the pretensions of metaphysics we put an unpretentious poetics, the various and irreducibly plural ways we have of giving figure and form to our experience of the unconditional, of giving it narratival and pictorial form, in words and images, striking sayings and dramatic scenes.”14

One can determine, from the above confession, that Jack’s philosophical poetics inculcate both an aporetics and an apophatics. As one travels near the limits of metaphysics, one desires to move beyond those limits, yet discovers that such transcendence is impossible. One may never totally escape the flux of existence and the limitations and uncertainties that the flux ensures. Poetics, then, is always un pas au-dela, “a step (not) beyond,”15 a movement—always a kinesis, never a stasis—that remains messianic, heading toward a destination always “to come.” As a result, discourse remains within the embrace of the negative, wrestling constantly with the inability to articulate certainty and truth without tapping out and conceding to the functional ineffability of such articulations. Poetics, therefore, constantly speaks about how to avoid speaking, thereby remaining both apophatic and loquacious.

One encounters an early expression of the aporetic/apophatic nature of Jack’s developing poetics simply by reading the first two selections in the current anthology, the two parts of “Meister Eckhart and the Later Heidegger.” I consider it quite appropriate to begin a Caputo reader with textual evidence of the centrality of Christian mysticism and Meister Eckhart for his radical hermeneutics. During the forty years since the publication of these essays, he has continually extrapolated the critical implications of mystery and negative theology for developing an alternative discourse to the traditional philosophical language of foundationalism and its craving for certainty. Furthermore, the specific context of Eckhartian mysticism emphasizes the theological sensitivity that has consistently characterized his thought. Although he has openly been identified as a “theologian” only for the past decade or so, he has effectively been doing theology throughout his career. He concedes as much on a couple of occasions: first when he testifies that God has been “a lifelong task”16 and second when he acknowledges “a weakness for theology.”17 One may well say of Caputo what he says of Heidegger, that he “has been interested in theological issues from the very beginning of his studies” and for decades has been “transforming the ideas and the language of the Western religious tradition.”18

Ironically, Jack’s obsession with theology leads to a certain subversion of Derrida, who early on in his work identifies the totalizing dynamic of metaphysics as specifically “theological,” with “God” serving as the “transcendental signified” that ensures a closure to meaning and truth.19 Jack, on the other hand, develops an understanding of “God” as precisely a name for the event that keeps reality open to mystery and preempts every attempt at reconstructing some type of Cartesian certainty. “God” names the ateleological interruptive spirit that acts as a quasi-transcendental for the continuation of poetics.20 Poetics can now be theological (theopoetics) and religious in the more radical sense of the anonymity of the call to something impossible, something unprogrammable, something that respects ethical alterity, and something that deconstructs every status quo—for example, something like a poetics of the Kingdom of God. In the interest of full disclosure, therefore, I must now complete the quotation above referencing Jack’s manifesto of poetics:

In the place of the pretensions of metaphysics we put an unpretentious poetics, the various and irreducibly plural ways we have of giving figure and form to our experience of the unconditional, of giving it narratival and pictorial form, in words and images, striking sayings and dramatic scenes, which is what we mean by a theopoetics of the folly of God. Religion is a song to the unconditional, a way to sing what lays claim to us unconditionally. But as to identifying what the unconditional is, if it is, we beg to be excused. This is a hermeneutics where nobody has the key, the code, the legendum (emphasis added).21

For Jack, a “theopoetics of the folly of God” translates quite easily into a theology of the event, which is, in itself, a theology of the “perhaps.” Indeed, he clearly distinguishes logic from poetics at this very point, insisting that “[l]ogic addresses the modally possible, whereas a poetics is always a grammar of the ‘perhaps,’ which is the prime modality of the event…. [I]n a poetics the possible belongs to the humble sphere of what Derrida calls the ‘perhaps,’ the peut-être. The peut-être threatens to irrupt from within and to disturb the conditions of être, supplying the dangerous perhaps of the possibility of the impossible that solicits us from afar.”22

I allege that one may validly read Caputo’s corpus as expressing several different, yet complementary, variants of poetics, each emerging in some manner out of two concepts, the “without” and the “perhaps.” These two concepts are among Jack’s favorite words. He uses, not just mentions, them constantly, whether in English, German, or French. From his dependence noted above on Angelus Silesius’s ohne warum, “without why,” concerning the rose’s propensity to bloom with no concern for the Principle of Sufficient Reason to his glosses on Derrida’s “religion without religion,” where he speaks of faith as “sans vision, sans verité, sans révelation” or “sans voir, sans avoir, sans savoir,” Jack is never without access to the “without.”23 Likewise, he consistently advocates the centrality of the “perhaps,” here again utilizing the Derridean translation of that concept. Derrida does not define peut-être in its literal etymological sense of “may” (peut) “be” (être) but in the more active sense of “it may happen.”24 Derrida’s paraphrase of peut-être, therefore, directly connects “perhaps” with the idea of the “event,” another one of those ideas that Jack endorses throughout his corpus, especially with reference to his theology. He declares that the event just happens without why and without the compulsion of the preordained. It cannot be programmed or anticipated by the inexorability of logic, the necessity of causality, or the manipulation of individual or social sovereignty. It remains messianic, always “to come” in some absolute future that will have been but never is—one of the only “absolutes” that Jack allows!25 Consequently, the event subverts every dissimulation of totalized meaning, or hegemonic capital T truth, or reductionistic claim to certainty. In “On Not Knowing Who We Are” (chapter 10 in this reader), Jack refers to this condition using Foucault’s phrase the “night of truth,” which ultimately denies the “truth of truth.”26 Concomitantly, the event grounds only the ungrounded “perha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Part One. Radical Hermeneutics: Reflections

- Part Two. Radical Hermeneutics: Selections

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Essential Caputo by B. Keith Putt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophie & Philosophie de la religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.