![]()

1A Short Sketch of the Fergana Valley

FERGANA IS A VALLEY that runs from northeast to southwest, surrounded by mountain ranges that open up only to its southwestern corner, near Khujand.

The length of the valley from Khujand to Uzgentom (in [geographic] projection) is approximately 300 versts.1 The greatest distance between the base of the foothills is about 130 versts, and the smallest (near Maxram), about 30 versts. Longitudinally, the valley is cut by the river Syr-Darya, formed from the junction of the Naryn and Kara-Darya Rivers, a few versts to the south of Namagan. Many small rivers and streams run down the mountain slopes and partly in the foothills, but mainly when they flow into the valley, their flow diverges into an enormous network of ariqs, artificial irrigation channels.

The major cities, the most populated trade and industrial settlements, are Qo’qon [Kokand], Marg’ilon, Andijon, Namangan, Osh, and Chust. Apart from these cities, which correspond to six current uezds [administrative divisions or regions] of Fergana oblast’ [province], there are kishlaks (villages), some of which—for example, Isfara and Rishtan of Qo’qon region, Shaxrixon and Assaka of Marg’ilon region, and Uzgent of Andijon region—compare in size and population to such cities as Osh and Chust.

Depending on the local climate, all cultivated crops (grains, vegetables, fruit, and nonfruit trees) can be grown only provided that the soil is artificially irrigated, and that is why cultivated lands, planted trees, and sedentarization can be found only where local conditions were conducive to construction of ariqs.

If you could look at Fergana in the summer a vol d’oiseau [with a bird’s-eye view], its lowlands would appear in hues of gray and yellow from the sand and saline steppes, almost devoid of vegetation, with occasional patches of greenery. These spots are cultivated oases nurtured by the local irrigation systems, large and small, the beauty and grandeur of middle Asia.

The characteristic features of the modern oases are so similar that they really differ only in size. In general, each large oasis that contains a city (or a large market kishlak) appears thus:

The external border of the elliptically shaped oasis has rather large plots of unfenced, cultivated fields where wheat, grain, lucerne [alfalfa], cotton, and beets are grown. The closer we get to the center of the oasis, the smaller the plots become, their cultivation visibly improves, and the more frequently one finds fields protected by rammed earth walls 1½ to 2 arshin in height,2 inside of which grow mulberry (for sericulture), poplar, and other trees, with the above-mentioned crops plus vegetables (melons, watermelons, carrots, and onions), tobacco, and occasional vineyards. Further, there are almost no unfenced fields; the plots are bordered by few or many trees, in one line or in a double row. These are mainly mulberry trees, poplars, willows, and Russian olives.3 Many places are shaded by elms and walnuts. Grain crops are almost completely replaced by vegetables, lucerne, and vineyards; on the roads one meets more and more araba,4 some empty and some loaded; more people walking or riding horses; on all sides at every step there are gardens with vineyards, pomegranate trees, apples, pears, plums, cherries, walnuts, mulberries, poplars, and elms. Finally, the city itself begins.

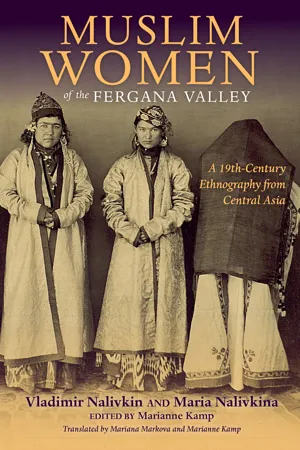

The streets are always narrow; often two arabas can pass each other only with difficulty by scraping axle tips on neighboring fences and the walls of the houses, or in cases when they cannot pass, one of the arabas has to be backed by its horse till it reaches the nearest cross street, which it enters to let the other cart pass by. That is how narrow the streets are. The streets are lined by gray, rammed-earth walls5 of one-story houses, with flat, earthen roofs and no windows facing the street; the fences, also of clay, are similar; the gates and wicket doors are small. The town turtledoves look like Egyptian doves; slim, suspicious-looking, scabby dogs in the streets, on the roofs, and on the walls, from which they bark at people that pass or drive by. Half-naked, dirty, and nevertheless very good-looking boys and girls play in the dust of the street, and if they are not run down in dozens, it is only because Sarts regard riding at a swift pace as unacceptable. Sart women, with faces covered by a black [horse]hair net, in gray paranjis, robes with long sleeves, draped from the head, while the hem and the ends of the sleeves drag behind or at least reach the ground, move along alone or in twos, carrying children in their arms and bundles of silk cocoons on their heads, in a light, slightly hasty gait, by their gray figures reminding one more of mummies than living human beings.

[Male] Sarts in cotton-print, quilted, or occasionally silk robes or white or striped shirts in the same style as the robes and made from local cotton fabrics, in turbans and skullcaps, barefooted or in leather boots with outer galoshes, walking, riding horses, or on arabas; Jewish dyers wearing similar dress but with long side locks and hands always blue from dye; two or three Indians;6 a Kyrgyz in a fur hat riding a small, bony nag with a roped-together line of camels; a small ariq cutting the street, with a stone slab over it instead of a small bridge. On the left, you can see the mosque with a flat, earthen roof open from the eastern side, its inside covered with white plaster, niches in the walls, various pillars, and a brightly painted ceiling; the yard has a pond with huge, shady elms planted around it; the entrance gate’s base is a good arshin below ground level, with a grating at the bottom to prevent animals entering, which could desecrate this holy space for every Muslim; the faithful have to climb over that grating to enter.

The bazaar. From afar, one can smell the unpleasant, sharp odor of sesame oil, which is used right on the spot in the bazaar to prepare various foods; the buzz of hundreds or thousands of human voices, carrying out trade; the rattle of blacksmith’s hammers and the neigh of horses. From time to time, there is a shrill bellow of a camel. Streets in the bazaar are much wider than the town’s other streets. Shops, small or tiny, line both sides of the street; most have small, bulrush sunshades standing on thin willow switches. This is where blacksmiths, harness makers, saddlers, tailors, silversmiths, and coppersmiths work and trade; in the midst of these, qassob (butchers) and baqqol (petty grocers) sell meat, melons, carrots, peppers, onions, oil, rice, and tobacco.

Here is a small shop with books; next to it dumplings and pies are made and sold;7 further on, fur coats are curried; here a kudungar uses a mallet made of elm to beat a brightly colored, intricately patterned atlas [silk fabric];8 a Maddah, covered with sweat, his eyes popping out in ecstasy, walks up and down waving his hands and striking his chest with a fist, shrilly reciting the biography of some Muslim saint. Further on, there is a line of open-air stores with felts, lassoes made of [horse]hair, woolen sacks, and other similar items; the halvah seller screams “shakar-dak” (like sugar) at the top of his voice; from another direction, as if in answer, comes “muz-dak, sharbat!” (sherbet cold as ice!). On the corner in the choy-xona (teahouse) several well-dressed Sarts sit in a half circle, facing the bazaar, with a bachcha, a cheesy, dolled-up boy in their midst, drinking tea and smoking chilim, the local water pipe made of cane. Further on, there are long lines of covered shops with expensive goods, cottons, red calico, padding, scarves, most of them in the brightest of colors. In front of one of the shops a whole company of holy fools, devona, wearing kuloh, high conical hats from a red fabric, with long staffs, with gourds at their waist instead of our beggar’s bags, sing and beg for alms; the storekeeper avoids looking at them and starts a conversation with one of the Sarts passing by. On the other side of the street, an isiriqchi, another holy fool, runs around in the crowd, fumigating the passersby with smelly smoke of an herb, isiriq, to protect them from the approach of shaitan (the devil) and begging for alms in return. On the left, there is a line of stores with pieces of cloth hanging on the walls, atlas, kanaus, iparkak, adras,9 and other silk fabrics; further on, attors are sitting selling buttons, different kinds of fasteners, medicines, looking glasses, cosmetics, and other things; there are several shops with skullcaps of various patterns and colors. A group of loiterers is entertained by an Afghani with a dancing monkey that also performs a soldier walking with a rifle, a hunter crawling to catch game, and other tricks. A large open gate reveals the inside of a caravanserai, a spacious yard with a line of tiny hujra, or cells, along the walls, with huge scales, piles of leather, iron fetters, pots, and yokes, with potbellied Sart merchants, with nimble, comely clerks, with Kyrgyz cart men, and, finally, with a Russian clerk in a service cap carrying a thick notebook.

Not far from the bazaar is the o’rda, the citadel or former residence of the bek or hokim who managed this viloyat [province], where one can still find an old-fashioned copper artillery cannon on the bulwark and a sentry wearing a white shirt with epaulettes and a service cap. In the distance, beyond the thick willows and tall poplars, the windows and white walls of Russian houses appear. An officer in a white military jacket and service cap heads toward the citadel; a soldier’s wife is carrying a bundle of washed and starched laundry;10 a Russian fine lady and her daughter, wearing hats, are hiding under umbrellas; a Sart cart driver passes in a very wobbly hackney cab; several soldiers follow; a Russian store with two windows and a sign “Trade in groceries”; another one across the street says, “Take-out Drinks”; a post office with two lampposts painted in the ordinary brownish-green color; a telegraph; empty streets lined with trees planted very close to each other; a long white military barrack at one end; quiet, and above all of this a transparent blue sky, the sun so bright that it is impossible to look at any of the gray, clay fences for a long time because their shimmer reflects its burning, nearly vertical rays; and to finalize the picture, 41 degrees Celsius in the shade [106°F].

Kishlak village bazaars are, naturally, much smaller than in the cities; the trade is mainly bread and other agricultural produce; the selection of other goods is very limited, and most of them, including items of indigenous mastery, cannot be found at all. With exception of Qo’qon and Marg’ilon, bazaar days occur once a week. The other six days of the week, other than meat and vegetable shops and the choy-xona, only a few shops are open and only in the cities.

In the cities, between sunset and sunrise, only night watchmen can remain in the bazaar. (The Muslim religion recommends not carrying out trade at night, first, so that there is no competition with those sellers who cannot work at night, for some reason, and, second, because things should be sold when they can be measured and viewed without impediment.)

The number of kishlaks with a bazaar is relatively large. For instance, there were five bazaars in Namagan district, which has an area of 5,600 square versts and a population of about one hundred thousand.

As we mentioned earlier, cultivation and sedentary life depend here, first, on building ariqs, which, in turn, depends on the presence or absence of water suitable for irrigation as well as on land contours. The same reasons underlie the vast differences in the sizes of the oases and the distances between them.

Kishlaks vary between one hundred and two hundred households. In places where Kipchaks, Karakalpaks, Kurama, and the recently settled Kyrgyz make up the majority, kishlaks (unwalled villages) are relatively rare, and instead, there are qo’rg’oncha, settlements surrounded by tall walls, with battlements that have arrow slits. In the murky past, these served as small fortresses, which is how they got their name. (Qo’rg’on means a fortress; qo’rg’oncha, a small fortress.)

Now we would like to say a few words about the climate of the country that we are describing. Spring, and the start of agricultural fieldwork, begins in late February or early March. In terms of vegetation, spring is observed when some grasses (iris) appear and almond and apricot trees blossom. In May, heat brings the strongest flow of water in rivers and mountain streams because of mountain snowmelt. At about the same time, mulberries, apricots, and barley ripen. Wheat ripens in June. Grapes and maize, in July. Nights in June and July are sweltering, and myriad mosquitoes and sand flies make the heat even more unbearable. In August, the heat gradually recedes, nights become cooler, and mosquitoes slowly disappear. The warm, dry autumn starts in early October. By late October, jugara (sorghum), cotton, and rice ripen.

Winter, when temperatures drop below 0 degrees Celsius [32°F], usually starts in late November or early December and lasts till the middle of February. In the years when winters are cold, the temperature often drops below 23 degrees C; while, generally, the average temperature for December and January is between 5 and 15 degrees C.11

This description applies to the valley floor (Namangan, 1,340 feet above sea level; Marg’ilon, 1,480; Andijon, 1,512; see the map of Fergana Province published in 1879).12

As we approach the mountains, the landscape gradually rises above sea level, and the length of the summer and...